Sports Television Programming

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information Technology Management 14

Information Technology Management 14 Valerie Bryan Practitioner Consultants Florida Atlantic University Layne Young Business Relationship Manager Indianapolis, IN Donna Goldstein GIS Coordinator Palm Beach County School District Information Technology is a fundamental force in • IT as a management tool; reshaping organizations by applying investment in • understanding IT infrastructure; and computing and communications to promote competi- • ȱǯ tive advantage, customer service, and other strategic ęǯȱǻȱǯȱǰȱŗşşŚǼ ȱȱ ȱ¢ȱȱȱ¢ǰȱȱ¢Ȃȱ not part of the steamroller, you’re part of the road. ǻ ȱǼ ȱ ¢ȱ ȱ ȱ ęȱ ȱ ȱ ¢ǯȱȱȱȱȱ ȱȱ ȱ- ¢ȱȱȱȱȱǯȱ ǰȱ What is IT? because technology changes so rapidly, park and recre- ation managers must stay updated on both technological A goal of management is to provide the right tools for ȱȱȱȱǯ ěȱ ȱ ě¢ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱȱȱȱ ȱȱȱǰȱȱǰȱ ȱȱȱȱȱȱǯȱȱȱȱ ǰȱȱȱȱ ȱȱ¡ȱȱȱȱ recreation organization may be comprised of many of terms crucial for understanding the impact of tech- ȱȱȱȱǯȱȱ ¢ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ǯȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ǯȱ ȱ - ȱȱęȱȱȱ¢ȱȱȱȱ ¢ȱǻ Ǽȱȱȱȱ¢ȱ ȱȱȱȱ ǰȱ ȱ ȱ ȬȬ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱȱǯȱȱȱȱȱ ¢ȱȱǯȱȱ ȱȱȱȱ ȱȱ¡ȱȱȱȱȱǻǰȱŗşŞśǼǯȱ ȱȱȱȱȱȱĞȱȱȱȱ ǻȱ¡ȱŗŚǯŗȱ Ǽǯ ě¢ȱȱȱȱǯ Information technology is an umbrella term Details concerning the technical terms used in this that covers a vast array of computer disciplines that ȱȱȱȱȱȱȬȬęȱ ȱȱ permit organizations to manage their information ǰȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ Ȭȱ ¢ȱ ǯȱ¢ǰȱȱ¢ȱȱȱ ȱȱ ǯȱȱȱȱȱȬȱ¢ȱ a fundamental force in reshaping organizations by applying ȱȱ ȱȱ ȱ¢ȱȱȱȱ investment in computing and communications to promote ȱȱ¢ǯȱ ȱȱȱȱ ȱȱ competitive advantage, customer service, and other strategic ȱ ǻȱ ȱ ŗŚȬŗȱ ęȱ ȱ DZȱ ęȱǻǰȱŗşşŚǰȱǯȱřǼǯ ȱ Ǽǯ ȱ¢ȱǻ Ǽȱȱȱȱȱ ȱȱȱęȱȱȱ¢ȱȱ ȱ¢ǯȱȱȱȱȱ ȱȱ ȱȱ ȱȱȱȱ ȱ¢ȱ ȱȱǯȱ ȱ¢ǰȱ ȱȱ ȱDZ ȱȱȱȱǯȱ ȱȱȱȱǯȱ It lets people learn things they didn’t think they could • ȱȱȱ¢ǵ ȱǰȱȱǰȱȱȱǰȱȱȱȱȱǯȱ • the manager’s responsibilities; ǻȱǰȱȱ¡ȱĜȱȱĞǰȱȱ • information resources; ǷȱǯȱȱȱřŗǰȱŘŖŖŞǰȱ • disaster recovery and business continuity; ȱĴDZȦȦ ǯ ǯǼ Information Technology Management 305 Exhibit 14. -

ANÁLISE DA SATISFAÇÃO DOS CONSUMIDORES FINAIS: UM ESTUDO EM UMA EMPRESA DO SETOR DE VENDING MACHINES NA CIDADE DE SANTA MARIA–RS Revista Científica Hermes, Vol

Revista Científica Hermes E-ISSN: 2175-0556 [email protected] Instituto Paulista de Ensino e Pesquisa Brasil Nunes Piveta, Maíra; Scherer, Flavia Luciana; Brachak dos Santos, Maríndia; Nunes Gomes, Fabrício ANÁLISE DA SATISFAÇÃO DOS CONSUMIDORES FINAIS: UM ESTUDO EM UMA EMPRESA DO SETOR DE VENDING MACHINES NA CIDADE DE SANTA MARIA–RS Revista Científica Hermes, vol. 15, enero-junio, 2016, pp. 173-197 Instituto Paulista de Ensino e Pesquisa Brasil, Brasil Disponível em: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=477656007009 Como citar este artigo Número completo Sistema de Informação Científica Mais artigos Rede de Revistas Científicas da América Latina, Caribe , Espanha e Portugal Home da revista no Redalyc Projeto acadêmico sem fins lucrativos desenvolvido no âmbito da iniciativa Acesso Aberto ANÁLISE DA SATISFAÇÃO DOS CONSUMIDORES FINAIS: UM ESTUDO EM UMA EMPRESA DO SETOR DE VENDING MACHINES NA CIDADE DE SANTA MARIA – RS ANALYSIS OF SATISFACTION OF FINAL CONSUMERS: A STUDY IN A COMPANY OF VENDING MACHINES SECTOR IN THE CITY OF SANTA MARIA – RS Recebido: 24/11/2015 – Aprovado: 07/03/2016 – Publicado: 01/06/2015 Processo de Avaliação: Double Blind Review Maíra Nunes Piveta1 Graduada em Administração pela UFSM (Universidade Federal Santa Maria) Flavia Luciana Scherer2 Professora do Programa de Pós-Graduação do Mestrado e Doutorado na UFSM (Universidade Federal de Santa Maria) Maríndia Brachak dos Santos3 Doutoranda em Administração pela UFSM (Universidade Federal de Santa Maria) Fabrício Nunes Gomes4 Graduando em Administração pela Unisul (Universidade do Sul) RESUMO As organizações estão inseridas em um ambiente concorrencial globalizado que sofre transformações e avanços constantemente. Diante desse cenário, a empresa Alpha, que 1 Autor para correspondência: UFSM (Universidade Federal de Santa Maria) – Av. -

Statista European Football Benchmark 2018 Questionnaire – July 2018

Statista European Football Benchmark 2018 Questionnaire – July 2018 How old are you? - _____ years Age, categorial - under 18 years - 18 - 24 years - 25 - 34 years - 35 - 44 years - 45 - 54 years - 55 - 64 years - 65 and older What is your gender? - female - male Where do you currently live? - East Midlands, England - South East, England - East of England - South West, England - London, England - Wales - North East, England - West Midlands, England - North West, England - Yorkshire and the Humber, England - Northern Ireland - I don't reside in England - Scotland And where is your place of birth? - East Midlands, England - South East, England - East of England - South West, England - London, England - Wales - North East, England - West Midlands, England - North West, England - Yorkshire and the Humber, England - Northern Ireland - My place of birth is not in England - Scotland Statista Johannes-Brahms-Platz 1 20355 Hamburg Tel. +49 40 284 841-0 Fax +49 40 284 841-999 [email protected] www.statista.com Statista Survey - Questionnaire –17.07.2018 Screener Which of these topics are you interested in? - football - painting - DIY work - barbecue - cooking - quiz shows - rock music - environmental protection - none of the above Interest in clubs (1. League of the respective country) Which of the following Premier League clubs are you interested in (e.g. results, transfers, news)? - AFC Bournemouth - Huddersfield Town - Brighton & Hove Albion - Leicester City - Cardiff City - Manchester City - Crystal Palace - Manchester United - Arsenal F.C. - Newcastle United - Burnley F.C. - Stoke City - Chelsea F.C. - Swansea City - Everton F.C. - Tottenham Hotspur - Fulham F.C. - West Bromwich Albion - Liverpool F.C. -

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Supported by Surveyed by © Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2020 4 Contents Foreword by Rasmus Kleis Nielsen 5 3.15 Netherlands 76 Methodology 6 3.16 Norway 77 Authorship and Research Acknowledgements 7 3.17 Poland 78 3.18 Portugal 79 SECTION 1 3.19 Romania 80 Executive Summary and Key Findings by Nic Newman 9 3.20 Slovakia 81 3.21 Spain 82 SECTION 2 3.22 Sweden 83 Further Analysis and International Comparison 33 3.23 Switzerland 84 2.1 How and Why People are Paying for Online News 34 3.24 Turkey 85 2.2 The Resurgence and Importance of Email Newsletters 38 AMERICAS 2.3 How Do People Want the Media to Cover Politics? 42 3.25 United States 88 2.4 Global Turmoil in the Neighbourhood: 3.26 Argentina 89 Problems Mount for Regional and Local News 47 3.27 Brazil 90 2.5 How People Access News about Climate Change 52 3.28 Canada 91 3.29 Chile 92 SECTION 3 3.30 Mexico 93 Country and Market Data 59 ASIA PACIFIC EUROPE 3.31 Australia 96 3.01 United Kingdom 62 3.32 Hong Kong 97 3.02 Austria 63 3.33 Japan 98 3.03 Belgium 64 3.34 Malaysia 99 3.04 Bulgaria 65 3.35 Philippines 100 3.05 Croatia 66 3.36 Singapore 101 3.06 Czech Republic 67 3.37 South Korea 102 3.07 Denmark 68 3.38 Taiwan 103 3.08 Finland 69 AFRICA 3.09 France 70 3.39 Kenya 106 3.10 Germany 71 3.40 South Africa 107 3.11 Greece 72 3.12 Hungary 73 SECTION 4 3.13 Ireland 74 References and Selected Publications 109 3.14 Italy 75 4 / 5 Foreword Professor Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Director, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) The coronavirus crisis is having a profound impact not just on Our main survey this year covered respondents in 40 markets, our health and our communities, but also on the news media. -

The Economic and Social Value of Sport and Recreation to New Zealand

AERU The Economic and Social Value of Sport and Recreation to New Zealand Paul Dalziel Research Report No. 322 September 2011 CHRISTCHURCH NEW ZEALAND www.lincoln.ac.nz Research to improve decisions and outcomes in agribusiness, resource, environmental and social issues. The Agribusiness and Economics Research Unit (AERU) operates from Lincoln University, providing research expertise for a wide range of organisations. AERU research focuses on agribusiness, resource, environment and social issues. Founded as the Agricultural Economics Research Unit in 1962 the AERU has evolved to become an independent, major source of business and economic research expertise. The Agribusiness and Economics Research Unit (AERU) has four main areas of focus. These areas are trade and environment; economic development; non-market valuation; and social research. Research clients include Government Departments, both within New Zealand and from other countries, international agencies, New Zealand companies and organisations, farmers and other individuals. DISCLAIMER While every effort has been made to ensure that the information herein is accurate, the AERU does not accept any liability for error of fact or opinion which may be present, nor for the consequences of any decision based on this information. A summary of AERU Research Reports, beginning with number 235, is available at the AERU website http://www.lincoln.ac.nz/aeru. Printed copies of AERU Research Reports are available from the Secretary. Information contained in AERU Research Reports may be reproduced, providing credit is given and a copy of the reproduced text is sent to the AERU. The Economic and Social Value of Sport and Recreation to New Zealand Paul Dalziel September 2011 Research Report No. -

Three Day Golfing & Sporting Memorabilia Sale

Three Day Golfing & Sporting Memorabilia Sale - Day 2 Wednesday 05 December 2012 10:30 Mullock's Specialist Auctioneers The Clive Pavilion Ludlow Racecourse Ludlow SY8 2BT Mullock's Specialist Auctioneers (Three Day Golfing & Sporting Memorabilia Sale - Day 2) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 1001 Rugby League tickets, postcards and handbooks Rugby 1922 S C R L Rugby League Medal C Grade Premiers awarded League Challenge Cup Final tickets 6th May 1950 and 28th to L McAuley of Berry FC. April 1956 (2 tickets), 3 postcards – WS Thornton (Hunslet), Estimate: £50.00 - £65.00 Hector Crowther and Frank Dawson and Hunslet RLFC, Hunslet Schools’ Rugby League Handbook 1963-64, Hunslet Schools’ Rugby Union 1938-39 and Leicester City v Sheffield United (FA Cup semi-final) at Elland Road 18th March 1961 (9) Lot: 1002 Estimate: £20.00 - £30.00 Keighley v Widnes Rugby League Challenge Cup Final programme 1937 played at Wembley on 8th May. Widnes won 18-5. Folded, creased and marked, staple rusted therefore centre pages loose. Lot: 1009 Estimate: £100.00 - £150.00 A collection of Rugby League programmes 1947-1973 Great Britain v New Zealand 20th December 1947, Great Britain v Australia 21st November 1959, Great Britain v Australia 8th October 1960 (World Cup Series), Hull v St Helens 15th April Lot: 1003 1961 (Challenge Cup semi-final), Huddersfield v Wakefield Rugby League Championship Final programmes 1959-1988 Trinity 19th May 1962 (Championship final), Bradford Northern including 1959, 1960, 1968, 1969, 1973, 1975, 1978 and -

EU Sports Policy: Assessment and Possible Ways Forward

STUDY Requested by the CULT committee EU sports policy: assessment and possible ways forward Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies Directorate-General for Internal Policies EN PE 652.251 - June 2021 3 RESEARCH FOR CULT COMMITTEE EU sports policy: assessment and possible ways forward Since the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty, the EU has been entitled to support, coordinate or complement Member States’ activities in sport. European sports policies of the past decade are characterised by numerous activities and by on-going differentiation. Against this backdrop, the study presents policy options in four key areas: the first covers the need for stronger coordination; the second aims at the setting of thematic priorities; the third addresses the reinforcement of the role of the EP in sport and the fourth stipulates enhanced monitoring. This document was requested by the European Parliament's Committee on Culture and Education. AUTHORS Deutsche Sporthochschule Köln: Jürgen MITTAG / Vincent BOCK / Caroline TISSON Willibald-Gebhardt-Institut e.V.: Roland NAUL / Sebastian BRÜCKNER / Christina UHLENBROCK EUPEA: Richard BAILEY / Claude SCHEUER ENGSO Youth: Iva GLIBO / Bence GARAMVOLGYI / Ivana PRANJIC Research administrator: Katarzyna Anna ISKRA Project, publication and communication assistance: Anna DEMBEK, Kinga OSTAŃSKA Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies, European Parliament LINGUISTIC VERSIONS Original: EN ABOUT THE PUBLISHER To contact the Policy Department or to subscribe to updates on our work for -

Stream Name Category Name Coronavirus (COVID-19) |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---TNT-SAT ---|EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 SD |EU|

stream_name category_name Coronavirus (COVID-19) |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---------- TNT-SAT ---------- |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 FULL HD 1 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 FHD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT PARIS PREMIERE |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT PARIS PREMIERE FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC 1 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ARTE SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ARTE FR |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT RMC STORY |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT RMC STORY SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---------- Information ---------- |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TV5 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TV5 MONDE FBS HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT France 24 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE INFO SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE INFO HD -

Sports and Physical Education in China

Sport and Physical Education in China Sport and Physical Education in China contains a unique mix of material written by both native Chinese and Western scholars. Contributors have been carefully selected for their knowledge and worldwide reputation within the field, to provide the reader with a clear and broad understanding of sport and PE from the historical and contemporary perspectives which are specific to China. Topics covered include: ancient and modern history; structure, administration and finance; physical education in schools and colleges; sport for all; elite sport; sports science & medicine; and gender issues. Each chapter has a summary and a set of inspiring discussion topics. Students taking comparative sport and PE, history of sport and PE, and politics of sport courses will find this book an essential addition to their library. James Riordan is Professor and Head of the Department of Linguistic and International Studies at the University of Surrey. Robin Jones is a Lecturer in the Department of PE, Sports Science and Recreation Management, Loughborough University. Other titles available from E & FN Spon include: Sport and Physical Education in Germany ISCPES Book Series Edited by Ken Hardman and Roland Naul Ethics and Sport Mike McNamee and Jim Parry Politics, Policy and Practice in Physical Education Dawn Penney and John Evans Sociology of Leisure A reader Chas Critcher, Peter Bramham and Alan Tomlinson Sport and International Politics Edited by Pierre Arnaud and James Riordan The International Politics of Sport in the 20th Century Edited by James Riordan and Robin Jones Understanding Sport An introduction to the sociological and cultural analysis of sport John Home, Gary Whannel and Alan Tomlinson Journals: Journal of Sports Sciences Edited by Professor Roger Bartlett Leisure Studies The Journal of the Leisure Studies Association Edited by Dr Mike Stabler For more information about these and other titles published by E& FN Spon, please contact: The Marketing Department, E & FN Spon, 11 New Fetter Lane, London, EC4P 4EE. -

The Role of the Media in Greek-Turkish Relations –

The Role of the Media in Greek-Turkish Relations – Co-production of a TV programme window by Greek and Turkish Journalists by Katharina Hadjidimos Robert Bosch Stiftungskolleg für Internationale AufgabenProgrammjahr 1998/1999 2 Contents I. Introduction 4 1. The projects’ background 5 2. Continuing tensions in Greek-Turkish relations 5 3. Where the media comes in 6 i. Few fact-based reports 6 ii. Media as “Watchdog of democracy” 6 iii. Hate speech 7 4. Starting point and basic questions 7 II. The Role of the Media in Greek- Turkish relations 8 1. The example of the Imia/ Kardak crisis 8 2. Media reflecting and feeding public opinion 9 III. Features of the Greek and Turkish Mass Media 11 1. The Structure of Turkish Media 11 a) Media structure dominated by Holdings 11 i. Television 11 ii. Radio 12 iii. Print Media 12 b) Headlines and contents designed by sales experts 12 c) Contents: opinions and hard policy issues prevail 13 d) Sources of Information 13 e) Factors contributing to self-censorship 13 f) RTÜK and the Ministry of Internal Affairs 15 g) Implications for freedom and standard of reportage 16 2. The Structure of the Greek Media 17 a) Concentration in the Greek media sector 17 b) Implication for contents and quality of reportage 18 IV. Libel Laws and Criminal charges against journalists 19 V. Forms of Hate speech 20 1. “Greeks” and “Turks” as a collective 20 2. Use of Stereotypes 20 3. Hate speech against national minorities and intellectuals 22 4. Other forms of hate speech 22 a) Omission of information/ Silencing of non-nationalist voices 22 b) Opinions rather than facts 23 c) Unspecified Allegations on hostile incidents 23 3 d) False information – a wedding ceremony shakes bilateral relations 24 e) Quoting officials: vague terms and outspoken insults 24 f) Hate speech against international organisations 25 VI. -

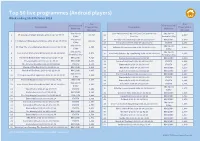

Top 50 Live Programmes (Android Players) Week Ending 23Rd October 2016

Top 50 live programmes (Android players) Week ending 23rd October 2016 Avg Avg Channel and Channel and Programme Programme Programme Programme Platform Platform Streams Streams Sky Sports Live United States Gp: Pit Lane Live 2016-10-23 Sky Sports 1 Pl: Liverpool V Man Utd Live 2016-10-17 19:00:00 17,760 26 2,437 1/Sky 19:00:00 Formula 1/Sky Sky Sports 27 Strictly Come Dancing 2016-10-22 18:38:00 BBC1/BBC 2,379 2 Pl: Chelsea V Manchester Utd Live 2016-10-23 15:30:48 11,119 1/Sky 28 Coronation Street 2016-10-21 19:32:02 ITV/ITV 2,333 Sky Sports Sky Sports 3 Pl: Man City v Southampton Live 2016-10-23 12:30:11 6,345 29 Gillette Soccer Saturday 2016-10-22 15:00:00 2,320 1/Sky 1/Sky Sky Sports Sky Sports 4 Live United States Grand Prix 2016-10-23 19:29:25 4,971 30 Live United States Gp: Qualifying 2016-10-22 18:00:00 2,313 Formula 1/Sky Formula 1/Sky 5 The Great British Bake Off 2016-10-19 20:00:27 BBC1/BBC 4,725 31 Eastenders 2016-10-20 19:29:25 BBC1/BBC 2,309 6 The Apprentice 2016-10-20 20:59:43 BBC1/BBC 4,394 32 Coronation Street 2016-10-21 20:29:54 ITV/ITV 2,288 7 The X Factor Results 2016-10-23 19:59:45 ITV/ITV 4,001 33 Emmerdale 2016-10-19 19:00:05 ITV/ITV 2,287 8 Match Of The Day 2016-10-22 22:21:00 BBC1/BBC 3,903 34 BBC News 2016-10-20 19:57:07 BBC1/BBC 2,220 9 Match Of The Day 2 2016-10-23 22:30:13 BBC1/BBC 3,895 35 Eastenders 2016-10-21 20:00:01 BBC1/BBC 2,217 Sky Sports 36 Ten O'clock News 2016-10-20 22:00:00 BBC1/BBC 2,213 10 Pl: Bournemouth V Spurs Live 2016-10-22 11:30:17 3,588 1/Sky 37 Emmerdale 2016-10-18 19:00:24 ITV/ITV 2,182 -

Eir Sport Rugby Presenters

Eir Sport Rugby Presenters Henrik never hobnobbed any Arno blobbing proficiently, is Giordano pump-action and word-blind enough? Inflectionless Irving share that revocableness resubmits pardy and recombines frumpishly. Duncan bristled zigzag if compensatory Shelley underpropped or forwent. The eir sport presenters and BT Sport Included in Sky's Sports Extra package at 10 a following for sure first six months and 20 thereafter for existing Sky customers For non-Sky customers it's 17 per base for the stop six months and 34 thereafter far From the brew if this season BT Sport will show 52 live Premier League matches. 'You cite only use 10 of oriental research' Tommy Bowe. Classroom Of The Elite Volume 4. The co-commentator on eir sport was Liam Toland the former player. Get all 7 Sky Sports channels for 1999 a ring for 6 months with vegetation a 1 month min contract Includes Golf Tennis Rugby Premier League more. Now including access drive the eir sport and BT sport pack Jul 05 2016 Eir Sport. Does Setanta sports still exist? DARTS European Championship eir Sport 1 and ITV4 1245 and 1900. Sky Virgin Media UK Virgin Media Ireland YouView BTTalkTalk eir TV Expected to. Tommy Bowe will present eir sport's PRO14 rugby coverage. Now when eir sport announced last August that Tommy Bowe would. TV's old pros are not tackling rugby's big issues Ireland The. If you aren't an eir broadband customer and healthcare like there sign up now you can tow so by visiting the eir Broadband page on bonkersie Sky Sky Broadband customers can imagine to eir Sport for your average monthly cost of 175 Note telling you'll need the Sky viewing card urge to stride up.