Toward a Theory of Market Culture: an Investigation of Value Co-Creation and the (Re)Contextualization of a Global Market Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

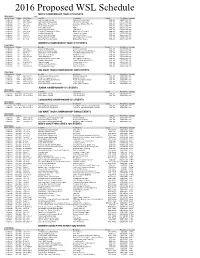

2016 Proposed WSL Schedule

2016 Proposed WSL Schedule MEN'S CHAMPIONSHIP TOUR (CT) EVENTS Event Status 2016 Tent/Confirmed Rating EventDates EventSite EventName Region PrizeMoney closedate Confirmed CT Mar 10-21 Gold Coast,Qld-Australia Quiksilver Pro Gold Coast WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT Mar 24-Apr 5 Bells Beach,Victoria-Australia Rip Curl Pro Bells Beach WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT Apr 8-19 Margaret River-West Australia Drug Aware Margaret River Pro WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT May 10-21 Rio de Janeiro,RJ-Brazil Rio Pro WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT Jun 5-17 Tavarua/Namotu-Fiji Fiji Pro WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT Jly 6-17 Jeffreys Bay-South Africa J Bay Open WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT Aug 19-30 Teahupo'o,Taiarapu Ouest-Tahiti Billabong Pro Teahupoo WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT Sep 7-18 Trestles,California-USA Hurley Pro at Trestles WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT Oct 4-15 Landes, South West France Quiksilver Pro France WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT Oct 18-29 Peniche/Cascais-Portugal Moche Rip Curl Pro Portugal WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A Confirmed CT Dec 8-20 Banzai Pipeline,Oahu-Hawaii Billabong Pipe Masters WSL Int'l US$551,000 N/A WOMEN'S CHAMPIONSHIP TOUR (CT) EVENTS Event Status Tent/Confirmed Rating EventSite EventName Region PrizeMoney closedate Confirmed CT Mar 10-21 Gold Coast,Qld-Australia Roxy Pro Gold Coast WSL Int'l US$275,500 N/A Confirmed CT Mar 24-Apr 5 Bells Beach,Victoria-Australia Rip Curl Women's Pro Bells Beach WSL Int'l US$275,500 N/A Confirmed CT Apr 8-19 Margaret -

07.09.07 Final Submission.Pdf (6.841Mb)

THE BREAK by Zubin Kishore Singh A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfi llment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Architecture Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2007 © Zubin Kishore Singh 2007 I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required fi nal revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Through surfi ng man enters the domain of the wave, is contained by and participates in its broadcast, measures and is in turn measured, meets its rhythm and establishes his own, negotiates continuity and rupture. The surfer transforms the surfbreak into an architectural domain. This thesis undertakes a critical exploration of this domain as a means of expanding and enriching the territory of the architectural imagination. iii Supervisor: Robert Wiljer Advisors: Ryszard Sliwka and Val Rynnimeri External Examiner: Cynthia Hammond To Bob I extend my heartfelt gratitude, for your generosity, patience and encouragement over the years, for being a true mentor and an inspiring critic, and for being a friend. I want to thank Val and Ryszard for their valuable feedback and support, as well as Dereck Revington, for his role early on; and I would like to thank Cynthia for sharing her time and her insight. I would also like acknowledge the enduring support of my family, friends and fellow classmates, without which this thesis could not have happened. iv For my parents, Agneta and Kishore, and for Laila. -

The Tragicomedy of the Surfers'commons

THE TRAGICOMEDY OF THE SURFERS ’ COMMONS DANIEL NAZER * I INTRODUCTION Ideally, the introduction to this article would contain two photos. One would be a photo of Lunada Bay. Lunada Bay is a rocky, horseshoe-shaped bay below a green park in the Palos Verdes neighbourhood of Los Angeles. It is a spectacular surf break, offering long and powerful rides. The other photograph would be of horrific injuries sustained by Nat Young, a former world surfing champion. Nat Young was severely beaten after a dispute that began as an argument over who had priority on a wave. These two images would help a non-surfer understand the stakes involved when surfers compete for waves. The waves themselves are an extraordinary resource lying at the centre of many surfers’ lives. The high value many surfers place on surfing means that competition for crowded waves can evoke strong emo- tions. At its worst, this competition can escalate to serious assaults such as that suffered by Nat Young. Surfing is no longer the idiosyncratic pursuit of a small counterculture. In fact, the popularity of surfing has exploded to the point where it is not only within the main- stream, it is big business. 1 And while the number of surfers continues to increase, * Law Clerk for Chief Judge William K. Sessions, III of the United States District Court for the District of Vermont. J.D. Yale Law School, 2004. I am grateful to Jeffrey Rachlinski, Robert Ellickson, An- thony Kronman, Oskar Liivak, Jason Byrne, Brian Fitzgerald and Carol Rose for comments and encour- agement. -

Marine Recreation Evidence Briefing: Surfing

Natural England Evidence Information Note EIN029 Marine recreation evidence briefing: surfing This briefing note provides evidence of the impacts and potential management options for marine and coastal recreational activities in Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). This note is an output from a study commissioned by Natural England and the Marine Management Organisation to collate and update the evidence base on the significance of impacts from recreational activities. The significance of any impact on the Conservation Objectives for an MPA will depend on a range of site specific factors. This note is intended to provide an overview of the evidence base and is complementary to Natural England’s Conservation Advice and Advice on Operations which should be referred to when assessing potential impacts. This note relates to surfing. Other notes are available for other recreational activities, for details see Further information below. Surfing (boardsport without a sail) Definition Watersports using a board (without a kite or sail) to ride surf waves. The activity group includes surfing, bodyboarding and kneeboarding. This note does not include windsurfing or kite surfing which are covered in a separate note. Distribution of activity Surfing is undertaken in close inshore waters where oceanographic and meteorological conditions combine with the local physical conditions (seabed bathymetry and topography), to create the desirable wave conditions for surfing. Access is directly off the beach and hence the activity is not limited by any access infrastructure requirements. First edition 27 November 2017 www.gov.uk/natural-england Marine recreation evidence briefing: surfing In general, the majority of surfing activity is undertaken off sandy shores although more experienced surfers surf off rocky shores (i.e. -

Gold Coast Surf Management Plan

Gold Coast Surf Management Plan Our vision – Education, Science, Stewardship Cover and inside cover photo: Andrew Shield Contents Mayor’s foreword 2 Location specifi c surf conditions 32 Methodology 32 Gold Coast Surf Management Plan Southern point breaks – Snapper to Greenmount 33 executive summary 3 Kirra Point 34 Our context 4 Bilinga and Tugun 35 Gold Coast 2020 Vision 4 Currumbin 36 Ocean Beaches Strategy 2013–2023 5 Palm Beach 37 Burleigh Heads 38 Setting the scene – why does the Gold Coast Miami to Surfers Paradise including Nobby Beach, need a Surf Management Plan? 6 Mermaid Beach, Kurrawa and Broadbeach 39 Defi ning issues and fi nding solutions 6 Narrowneck 40 Issue of overcrowding and surf etiquette 8 The Spit 42 Our opportunity 10 South Stradbroke Island 44 Our vision 10 Management of our beaches 46 Our objectives 11 Beach nourishment 46 Objective outcomes 12 Seawall construction 46 Stakeholder consultation 16 Dune management 47 Basement sand excavation 47 Background 16 Tidal works approvals 47 Defi ning surf amenity 18 Annual dredging of Tallebudgera and Currumbin Creek Surf Management Plan Advisory Committee entrances (on-going) 47 defi nition of surf amenity 18 Existing coastal management City projects Defi nition of surf amenity from a scientifi c point of view 18 that consider surf amenity 48 Legislative framework of our coastline 20 The Northern Beaches Shoreline Project (on-going) 48 The Northern Gold Coast Beach Protection Strategy Our beaches – natural processes that form (NGCBPS) (1999-2000) 48 surf amenity on the Gold Coast -

Volume 25 / No.1 / February 09

VOLUME 24 / NO.1 / JANUARY 08 VOLUME 25 / NO.1 / FEBRUARY 09 The Surfrider Foundation is a non-profit environmental organization dedicated TRACKING THE EBB AND FLOW OF to the protection and enjoyment of the world’s oceans, waves and beaches, for COASTAL ENVIRONMENTALISM all people, through conservation, activism, research and education. Publication of The Surfrider Foundation A Non-Profit Environmental Organization P.O. Box 6010 San Clemente, CA 92674-6010 Phone: (949) 492-8170 / (800) 743-SURF (7873) Web: www.surfrider.org / E-mail: [email protected] 109 victories since 1/06. The Surfrider Foundation is striving to win 150 environmental campaigns by 2010. For a list of these victories please go to: www.surfrider.org/whoweare6.asp Chief Executive Officer Washington Field Coordinator Jim Moriarty Shannon Serrano Chief Operating Officer California Policy Coordinator Michelle C. Kremer, Esq. Joe Geever Director of Chapters Washington Policy Coordinator Edward J. Mazzarella Jody Kennedy Environmental Director Ocean Ecosystem Manager Chad Nelsen Pete Stauffer The array of up to 18 spines on the Could crop residue help us ease the Director of Marketing & Communications Oregon Policy Coordinator top of the lionfish can deliver a painful, suffocation of our oceans or just cause Matt McClain Gus Gates sometimes nauseating—though not more damage? Director of Development Save Trestles Coordinator deadly—sting. Steve Blank Stefanie Sekich Assistant Environmental Director Ventura Watershed Coordinator Mark Rauscher Paul Jenkin Direct Mail Manager -

Surfing Injuries

Chapter 7 Sur fi ng Injuries Andrew T. Nathanson Contents Surfing: The Sport of Kings – History ................................................................................. 143 Demographics ......................................................................................................................... 145 Surfing Equipment ................................................................................................................. 147 Surfing, SUP, and Tow-In .............................................................................................. 147 Bodyboarding and Bodysurfing .................................................................................... 147 Wetsuits ......................................................................................................................... 148 Injury Rates and Risk Factors .............................................................................................. 148 Surfing Fatalities ........................................................................................................... 149 Acute Surfing Injuries ........................................................................................................... 149 Acute Injuries and Their Anatomic Distribution .......................................................... 149 Mechanisms of Injury ................................................................................................... 151 Overuse Injuries .................................................................................................................... -

Contesting the Lifestyle Marketing and Sponsorship of Female Surfers

Making Waves: Contesting the Lifestyle Marketing and Sponsorship of Female Surfers Author Franklin, Roslyn Published 2012 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School School of Education and Professional Studies DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/2170 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/367960 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au MAKING WAVES Making waves: Contesting the lifestyle marketing and sponsorship of female surfers Roslyn Franklin DipTPE, BEd, MEd School of Education and Professional Studies Griffith University Gold Coast campus Submitted in fulfilment of The requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy April 2012 MAKING WAVES 2 Abstract The surfing industry is a multi-billion dollar a year global business (Gladdon, 2002). Professional female surfers, in particular, are drawing greater media attention than ever before and are seen by surf companies as the perfect vehicle to develop this global industry further. Because lifestyle branding has been developed as a modern marketing strategy, this thesis examines the lifestyle marketing practices of the three major surfing companies Billabong, Rip Curl and Quicksilver/Roxy through an investigation of the sponsorship experiences of fifteen sponsored female surfers. The research paradigm guiding this study is an interpretive approach that applies Doris Lessing’s (1991) concept of conformity and Michel Foucault’s (1979) notion of surveillance and the technologies of the self. An ethnographic approach was utilised to examine the main research purpose, namely to: determine the impact of lifestyle marketing by Billabong, Rip Curl and Quicksilver/Roxy on sponsored female surfers. -

Question Asked Best Answer General Surfing My Answer Techniques/Endurance Need Help with a 6'5" Fish Surfboard? I Think You Probably Just Need a Little More Practice

The following questions were asked on Yahoo Answers with selected best answers provided by Bruce Gabrielson Question Asked Best Answer General Surfing My Answer Techniques/Endurance Need help with a 6'5" fish surfboard? I think you probably just need a little more practice. As you paddle I'm able to handle longboarding quite more the rocking will taper off and you will naturally develop better well and so before i left for college i got a balance. shorter board. it's a 6'5" fish with a round A couple of things to think about are how you take off with a short nose like a longboard. it's a very classic board and what you need to do immediately that you can't do well on fish style board. I've been able to catch a longboard. To start with, when you take off on your fish, lean some waves but a lot of the times i either forward and push your board down the face. You don't necessarily feel really shaky or as if I’m just going to need to paddle harder if you can get into the steep part of the wave a completely nose dive in. advice?? Also, little later than on a longboard. Also, you have more room to drop and paddling, I know you have to paddle turn with your fish. It will seem like you are too late to make the wave harder but i see people with these super since the transition from a longboard requires less room to maneuver short boards just gliding. -

Surfboard Blank Catalog

SurfboardSurfboard BlankBlank CatalogCatalog FOAM E-Z 6341 Industry Way #I Westminster, CA 92683 Phone (714) 896-8233 Fax (714) 896-0001 www.foamez.com Catalog current as of October , 2004 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION..................................... PAGE 1 As a consequence our catalog is often changed. We therefore do not produce a lot of catalogs in ad- PURPOSE ................................................. PAGE 1 vance but instead, make them as we need them. On the lower right corner of the front page we put the CURRENT VERSION OF CATALOG.... PAGE 1 date the catalog was printed. At the date of printing the catalog is current. Keep in mind that a few days DESCRIPTION OF BLANK PICTURES.. PAGE 1 later it might be changed. We realize the impor- tance of keeping customers updated on new close DENSITY INFORMATION ..................... PAGE 2 tolerance blanks, as they save the shaper a lot of time. We have a considerable investment in this STRINGER INFORMATION .................. PAGE 3 technology, and for this reason, we encourage shapers to request a current version of our catalog ROCKER INFORMATION ..................... PAGE 3 as often as they wish. INVENTORY MANAGEMENT TOOLS . PAGE 6 DESCRIPTION OF BLANK PICTURES MATERIAL SAFETY DATA SHEET .... PAGE 7 TO-SCALE BLANK PICTURES BLANK CODE DESCRIPTION .............. PAGE 9 . All blank pictures in this catalog are drawn to the REPLACEMENT BLANK LIST ............. PAGE 10 actual scale of the blanks. The blanks under 9 feet are on a scale of 1 to 12 and the blanks 9 feet and BLANK PICTURES ................................ PAGE 13 longer are on a scale of 1 to 16. The rocker is taken from the “natural” rocker template and is also to scale. -

SURFING SOUTH AFRICA LOCKDOWN APPEAL MAY 11Th

PO BOX 127, RONDEBOSCH, 7701 – [email protected] APPEAL FOR CONSIDERATION OF SURFING AND OTHER OCEAN SPORTS TO BE PERMITTED AS EXERCISE UNDER LOCKDOWN PREAMBLE Surfing South Africa, the official representative of the sport of Surfing in South Africa, is a member of the South African Sports Council Olympic Committee (SASCOC) and the International Surfing Association and partners with the World Surf League (WSL). The following disciplines fall under the Surfing South Africa umbrella: Surfing, Longboard Surfing, Bodyboarding, Kneeboarding, Para Surfing (Disabled) and Stand Up Paddlesurfing (SUP) are recognised affiliates. It is estimated that there are over 20,000 competitive and recreational surfers (all disciplines) in South Africa. Surfing is an ocean sporting activity that is carried out on the waves. All ocean sports, by their very nature, are naturally self-distancing. They require a person to have an existing level of expertise in the ocean and have minimal environmental impact. Some examples of Ocean Sports are Surfing, Longboarding, Bodyboarding, Para Surfing, Stand Up Paddle Surfing, Kneeboarding, Waveski, Surf Ski, Canoeing and Kayaking. All of the sports mentioned above are non-motorised, self - propelled and use the dynamic energy of waves to assist movement. 1. MOTIVATION 1. Ocean sports are only practiced in the ocean and there are relatively few venues where this can take place. 2. Ocean sportsmen and women do not congregate in groups. 3. Ocean sports do not involve any physical contact. 4. Ocean sports pose a lower health risk than cycling or running as any body fluids such as perspiration or saliva are immediately diluted in the sea water. -

Protecting Surf Breaks and Surfing Areas in California

Protecting Surf Breaks and Surfing Areas in California by Michael L. Blum Date: Approved: Dr. Michael K. Orbach, Adviser Masters project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Environmental Management degree in the Nicholas School of the Environment of Duke University May 2015 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................... vi LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................... vii LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................................ vii LIST OF ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................... viii LIST OF DEFINITIONS ................................................................................................................ x EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... xiii 1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 1 2. STUDY APPROACH: A TOTAL ECOLOGY OF SURFING ................................................. 5 2.1 The Biophysical Ecology ...................................................................................................... 5 2.2 The Human Ecology ............................................................................................................