Protecting Surf Breaks and Surfing Areas in California

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Observation of Rip Currents by Synthetic Aperture Radar

OBSERVATION OF RIP CURRENTS BY SYNTHETIC APERTURE RADAR José C.B. da Silva (1) , Francisco Sancho (2) and Luis Quaresma (3) (1) Institute of Oceanography & Dept. of Physics, University of Lisbon, 1749-016 Lisbon, Portugal (2) Laboratorio Nacional de Engenharia Civil, Av. do Brasil, 101 , 1700-066, Lisbon, Portugal (3) Instituto Hidrográfico, Rua das Trinas, 49, 1249-093 Lisboa , Portugal ABSTRACT Rip currents are near-shore cellular circulations that can be described as narrow, jet-like and seaward directed flows. These flows originate close to the shoreline and may be a result of alongshore variations in the surface wave field. The onshore mass transport produced by surface waves leads to a slight increase of the mean water surface level (set-up) toward the shoreline. When this set-up is spatially non-uniform alongshore (due, for example, to non-uniform wave breaking field), a pressure gradient is produced and rip currents are formed by converging alongshore flows with offshore flows concentrated in regions of low set-up and onshore flows in between. Observation of rip currents is important in coastal engineering studies because they can cause a seaward transport of beach sand and thus change beach morphology. Since rip currents are an efficient mechanism for exchange of near-shore and offshore water, they are important for across shore mixing of heat, nutrients, pollutants and biological species. So far however, studies of rip currents have mainly relied on numerical modelling and video camera observations. We show an ENVISAT ASAR observation in Precision Image mode of bright near-shore cell-like signatures on a dark background that are interpreted as surface signatures of rip currents. -

On-Shore Activities Off-Shore Activities (Non-Boating) Boating

MPA Watch Core Tally Sheet Name(s): Date: ___/___/_______ Transect ID: Clouds: clear (0%)/ partly cloudy (1- 50%)/ cloudy Start Time: End Time: Precipitation: yes / no (>50%cover) Air Temperature: cold / cool / mild / warm / Wind: calm / breezy / windy Tide Level: low / med / high hot Visibility: perfect / limited / shore only Beach Status: open / posted / closed / unknown On-Shore Activities Rocky Sandy Recreation (walking, resting, playing, etc. NOT tide pooling) Wildlife Watching Domestic animals on-leash Domestic animals off-leash Driving on the Beach Tide-pooling (not collecting) Hand collection of biota Shore-based hook and line fishing Shore-based trap fishing Shore-based net fishing Shore-based spear fishing Off-Shore Activities (Non-Boating) Offshore Recreation (e.g., swimming, bodysurfing) Board Sports (e.g., boogie boarding, surfing) Stand-Up Paddle Boarding (alternatively can tally in paddle operated boat below) Non-Consumptive SCUBA and snorkeling Spear Fishing (free diving or SCUBA) Other Consumptive Diving (e.g., nets, poles, traps) Boating Recreational Commercial Unknown Inactive Active Inactive Active Inactive Active Boat Fishing - Traps Boat Fishing - Line Boat Fishing - nets Boat Fishing - Dive Boat Fishing - Spear Boat Kelp Harvesting Unknown Fishing Boat Paddle Operated Boat (can separately tally stand-up paddle boarding above under board sports) Dive Boat (stationary – flag up) Whale Watching Boat Work Boat (e.g., life-guard, DFW, research, coast guard) Commercial Passenger Fishing Vessel (5+ people) Other Boating (e.g., powerboat, sail boat, jet ski) Comments Did you observe: ☐ scientific research; ☐ education; ☐ beach closure; ☐ large gatherings (e.g., beach cleanup); ☐ enforcement activity. Describe below and provide counts of individuals involved where possible, and whether it took place on rocky or sandy or sandy substrate. -

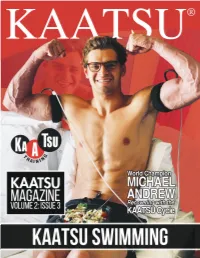

Michael Andrew in the KAATSU Cycle Recovery Mode KAATSU Swimming CONTENTSCONTENTS CONTENTSCONTENTSCONTENTS

KAATSUKAATSU® ® World Class Swimmer Michael Andrew in the KAATSU Cycle Recovery Mode KAATSU Swimming CONTENTSCONTENTS CONTENTSCONTENTSCONTENTS 44 66 1010 411411 646 10610 111011 11 KAATSUKAATSU AQUA AQUA HOWHOW NORTH NORTH SHORE SHORE KAATSUKAATSU AQUA AQUA CORECORE WORK WORK IN IN KAATSUKAATSU AQUA AQUA HOWHOW NORTH NORTH SHORE SHORE KAATSUKAATSU AQUA AQUA CORECORE WORK WORK IN IN BANDSBANDS HOW HOW TO TO LIFEGUARDSLIFEGUARDS TRAIN TRAIN BURPEESBURPEES THETHE WATER WATER WITH WITH KAATSU AQUA HOW NORTH SHORE KAATSU AQUA CORE WORK IN CONTENTSCONTENTS CONTENTSBANDSBANDS HOW HOW TO TO LIFEGUARDSLIFEGUARDS TRAIN TRAIN BURPEESBURPEES THETHE WATER WATER WITH WITH USEUSE IN IN POOL POOLCONTENTSCONTENTSCONTENTSWITHWITH KAATSU KAATSU KAATSUKAATSU AQUA AQUA BANDS HOW TO LIFEGUARDS TRAIN BURPEES THE WATER WITH CONTENTSCONTENTSCONTENTSCONTENTS USEUSE IN IN POOL POOL WITHWITH KAATSU KAATSU KAATSUKAATSU AQUA AQUA USE IN POOL WITH KAATSU KAATSU AQUA 44 46464 126121061046 191019111011106 2211221111 1012261226 111919 2222 2626 44KAATSU4KAATSU4 AQUA AQUA 6KAATSU6KAATSU66 AQUA AQUA 1010KAATSU10KAATSU10 AQUA AQUA FOR FOR 11HOW11HOW1111 KAATSU KAATSU 12 19 22 26 KAATSUKAATSU AQUA AQUA KAATSUKAATSU AQUA AQUA KAATSUKAATSU AQUA AQUA FOR FOR HOWHOW KAATSU KAATSU HOWHOW NORTH NORTH SHORE SHORE STRENGTH STRENGTH & & APPLICATIONSAPPLICATIONS FOR FOR BREASTSTROKERSBREASTSTROKERS CANCAN CHANGE CHANGE KAATSU AQUA KAATSU AQUA KAATSU AQUA FOR HOW KAATSU KAATSUKAATSU AQUA AQUA KAATSUKAATSUKAATSU AQUA AQUA AQUA HOWHOWKAATSUHOWKAATSU NORTH NORTH NORTH AQUA AQUA SHORE SHORE -

Part III-2 Longshore Sediment Transport

Chapter 2 EM 1110-2-1100 LONGSHORE SEDIMENT TRANSPORT (Part III) 30 April 2002 Table of Contents Page III-2-1. Introduction ............................................................ III-2-1 a. Overview ............................................................. III-2-1 b. Scope of chapter ....................................................... III-2-1 III-2-2. Longshore Sediment Transport Processes ............................... III-2-1 a. Definitions ............................................................ III-2-1 b. Modes of sediment transport .............................................. III-2-3 c. Field identification of longshore sediment transport ........................... III-2-3 (1) Experimental measurement ............................................ III-2-3 (2) Qualitative indicators of longshore transport magnitude and direction ......................................................... III-2-5 (3) Quantitative indicators of longshore transport magnitude ..................... III-2-6 (4) Longshore sediment transport estimations in the United States ................. III-2-7 III-2-3. Predicting Potential Longshore Sediment Transport ...................... III-2-7 a. Energy flux method .................................................... III-2-10 (1) Historical background ............................................... III-2-10 (2) Description ........................................................ III-2-10 (3) Variation of K with median grain size................................... III-2-13 (4) Variation of K with -

An Offshore Bank

Our Ocean Backyard –– Santa Cruz Sentinel columns by Gary Griggs, Distinguished Professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences, UC Santa Cruz. #271 September 16, 2018 An Offshore Bank Mountainous waves, crazy adventurers and sunken ships can all capture our interest and imagination, and there is a place off the coast of Southern California with a long history that includes all three of these. One-hundred and eleven miles due west of San Diego is an undersea mountain that rises a mile from the seafloor to within three feet of the ocean surface at low tides. Passing ships and small boats have even seen a few feet of rock exposed at the top of the mountain in the troughs of large waves from time to time. Cortes Bank appears to have been first sighted in 1846 by the frigate USS Constitution while transiting along the west coast from Monterey heading for engagement in the Mexican American War. Communication was somewhat limited in those days, however, and it was the captain of the steamship Cortes seven years later that believed he was the first to observe the waves breaking far out to sea over a shallow submarine feature in 1853. The shallow bank was named after his ship and the name stuck. It was that same year when the first U.S. Coast Survey map showed the presence of a navigational hazard in the area. The Stillwell S. Bishop, a clipper ship apparently hit the top of the seamount in 1855, but was able to continue on to San Francisco, leaving its name on the rock at the top of the bank, which it still carries today – Bishop Rock. -

NOR WALK HOTEL, and Stage House. MILLINERY EBENEZER

TREMOR AL,. t Cheag for Cash. PATENT HOES—AND ALE. Goods'. u _ i ( PUBLISHED BY 1\/| RS. M^jA. SELLECK has removed her T^HE subsciiber tiasrthi,sday received from T^HE subscribers have just received and of- TUST received by SMITH fe WlLSONj S.W.BENEDICT. fer for saje, a 'quantity, of warranted MILLINERY Establishment to the N. Yofk a general assortment of GRO • a large and handsome assortment of Cali^ TERMS.—Two Dollars p^r annum, payable building lately occupied, by DK Ansel Hoyt, CERIES, which he offers at reduced prices PATENT SPRING STEEL HOES,which coes ; plain and fig'd tiro deN?p and Levatii 'Quarterly. Mail subscribers in advance. will neither bend, batter nor. break—a very next door to the store she formerly occupied, Tor cash. The following articles are amdng tine Silks ; brown do. do. do.; Dr&is Hdkfs.| , less than a square, 75 superior article. Also—MOUNSEY'S best ' ADVERTISEMENTS where her customers are respectfully invited his assortment i black Levantine Hdkfs.; French and Italiari 'cents; a square, $1 00, for three insertions. to call. Norwalk, April 11. Cogniac and Cidar BRANDY'; Jamaica, STOCKJ3EER, which they will furnish to Crapes ; white G.VJze Vei\s ; Irish Linen j— &^xx^xxxxx x:xx>o<x,>o<>oC" St. Croix, & N. E. RtJM ; Holland & Coun Merchant and others as cheap as can be had OLD LINE. MILLINERY try GIN ; Young Hyson, Hyson Skin,, and in New-ifork.—It is earnestly re- iquested thif those indebted to the subscribers SUMMER ARRANGEMENT. " 11/1 RS. M. -

January LTS Specials

10-Jan-18 Community Recreation Division - Leisure Travel Service Fort Shafter LTS Schofield Barracks LTS (808) 438-1985 (808) 655-9971 January LTS Specials www.himwr.com/lts Discounted Attractions & Events Tickets Hawaii Attractions Complete Pricelist Attractions Polynesian Cultural Center - General Admission Expires: 30 April 2018 Adult: $33.00 / Child (4-11 yrs): $25.00 Cruises Dolphin Star - Wild Dolphin Watch Expires: 31 March 2018 2 Adult/Child (Ages 3 and up) for $66.00 Majestic Cruise - Appetizer Expires: 31 March 2018 **$10 of regular LTS rate. NOT valid on Friday Night Fireworks. Ages 7 and up: $49.00 Majestic Cruise - Island Buffet Expires: 31 March 2018 **$10 off the Adult Regular LTS rate. NOT valid on Friday Night Fireworks. Adult: $72.00 Majestic Cruise - Island Buffet BOGO Free Child Expires: 31 March 2018 **Buy One Adult and get the Child Free. NOT valid on Friday Night Fireworks. Adult: $82.00 / Child (7-12 yrs): FREE Majestic Cruise - Whale Watch Expires: 31 March 2018 **$10 off the Adult Regular LTS rate. Adult: $44.00 Majestic Cruise - Whale Watch Expires: 31 March 2018 **Buy One Adult and get the Child Free Adult: $54.00 / Child (7-12 yrs): FREE Star of Honolulu - Early Morning Whale Watch - No Meal Expires: 5 April, 2018 **Free Child with each paying adult, cruise only Adult: $30.00 Additional Child (3-11 yrs): $17.75 Star of Honolulu - Early Morning Whale Watch w/Breakfast Expires: 5 April, 2018 **Free Child with each paying adult, cruise only Adult: $40.50 Additional Child (3-11 yrs): $25.00 Child Meal Upgrade: -

Sherrill Genealogy

THE SHERRILL GENEALOGY THE DESCENDANTS OF SAMUEL SHERRILL OF EAST HAMPTON, LONG ISLAND NEW YORK BY CHARLES HITCHCOCK SHERRILL SECOND AND REVISED EDITION COMPILED AND EDITED BY LOUIS EFFINGHAM de FOREST CoPnxG:e:T, 1932, :BY CHARLES IDTCHCOCK SHERRILL THE TUTTLE, MOREHOUSE & TAYLOR COMPANY, KEW KA.VEN, CONK. SHERRILL THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED TO MY SHERRILL ANCESTORS WHO SERVED THE STATE EITHER LOCALLY OR NATIONALLY AND TO MY DESCENDANTS WHO SHALL ALSO DO SO TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE.. Editorial Note . vu Introduction ......................................•... 1 First Generation ..................................... 24 Second Generation . .............••... 31 Third Generation ....................................• 34 Fourth Generation . •• 41 Fifth Generation . 58 Sixth Generation . 98 Seventh Generation ................................... 151 Eighth Generation . ............................. 201 Ninth Generation .................................... 229 Tenth Generation . .................. 236 Bibliography . ................. 237 Index of Persons . ............... 241 V EDITORIAL NOTE The first edition of this work was compiled by Charles Hitchcock Sherrill and published privately by him in the year 1894. In this second and revised edition General Sherrill has written the entire Introduction and First Generation which are signed with his name. The editor assumes the usual responsibility for the remainder of the book and hopes that it will be acceptable to the Sherrills and to his fellow genealogists. The arrangement of material is the one generally found in modem genealogies. Each head of a family is given a number, in a sequence beginning with the first settler who is No. 1. By looking ahead to the given number the succeeding generation will 4 be found. The superior or raised numbers ( as Jonathan ) indicate the degree of descent from the founder of the family in America. The usual abbreviations are used. -

Groundwater on the Rise Mages of Houses Tumbling Into Lake Delton During Record Rainfalls in June 2008 Remain Etched in Our Memories

Winter 2010 Aquatic Sciences Chronicle ASCwww.aqua.wisc.edu/chronicle UniverSity of WisconSin SeA GrAnt inStitUte UniverSity of WisconSin WAter reSoUrCeS inStitUte inSide: 4 Visibility Impresses Visitor 5 Asian Carp Online & 6 Outside the Classroom Madeline Gotkowitz water reSoUrCeS oUtreach GroUndwater on the riSe mages of houses tumbling into Lake Delton during record rainfalls in June 2008 remain etched in our memories. The 17 inches of rain that fell over southern Wisconsin in a i10-day period caused catastrophic flooding, and not just from overflowing streambanks. Another more unusual type of flooding took place at the same time, less than 50 miles away. About 4,300 acres of land located near Spring Green but not in the Wisconsin River floodplain became inundated with water—water that rose from the ground and overtopped the land surface. This was groundwater flooding. The land remained under water for more than five months. No amount of pumping would reduce the water level because there was no place for it to drain. “People didn’t understand what was going on because normally water has a place to go,” stated Madeline Gotkowitz, a hydrologist from the Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey. continued on page 7 >> Water surrounds a house in Spring Green. The flood was caused by ground- water flooding, instead of the more common surface water flooding. University of Wisconsin Aquatic Sciences Chronicle University of Wisconsin Aquatic Sciences Center feAtUred Web tool 1975 Willow Drive Madison, WI 53706-1177 Social Networking Telephone: (608) 263-3259 twitter.com/WiscWaterlib E-mail: [email protected] 8 For many people, the phrase “social networking” con- The Aquatic Sciences Center is the administra- jures up images of teenagers late at night, composing tive home of the University of Wisconsin Sea messages about their favorite rock bands. -

MOSQUITOES of the SOUTHEASTERN UNITED STATES

L f ^-l R A R > ^l^ ■'■mx^ • DEC2 2 59SO , A Handbook of tnV MOSQUITOES of the SOUTHEASTERN UNITED STATES W. V. King G. H. Bradley Carroll N. Smith and W. C. MeDuffle Agriculture Handbook No. 173 Agricultural Research Service UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE \ I PRECAUTIONS WITH INSECTICIDES All insecticides are potentially hazardous to fish or other aqpiatic organisms, wildlife, domestic ani- mals, and man. The dosages needed for mosquito control are generally lower than for most other insect control, but caution should be exercised in their application. Do not apply amounts in excess of the dosage recommended for each specific use. In applying even small amounts of oil-insecticide sprays to water, consider that wind and wave action may shift the film with consequent damage to aquatic life at another location. Heavy applications of insec- ticides to ground areas such as in pretreatment situa- tions, may cause harm to fish and wildlife in streams, ponds, and lakes during runoff due to heavy rains. Avoid contamination of pastures and livestock with insecticides in order to prevent residues in meat and milk. Operators should avoid repeated or prolonged contact of insecticides with the skin. Insecticide con- centrates may be particularly hazardous. Wash off any insecticide spilled on the skin using soap and water. If any is spilled on clothing, change imme- diately. Store insecticides in a safe place out of reach of children or animals. Dispose of empty insecticide containers. Always read and observe instructions and precautions given on the label of the product. UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Agriculture Handbook No. -

The Tragicomedy of the Surfers'commons

THE TRAGICOMEDY OF THE SURFERS ’ COMMONS DANIEL NAZER * I INTRODUCTION Ideally, the introduction to this article would contain two photos. One would be a photo of Lunada Bay. Lunada Bay is a rocky, horseshoe-shaped bay below a green park in the Palos Verdes neighbourhood of Los Angeles. It is a spectacular surf break, offering long and powerful rides. The other photograph would be of horrific injuries sustained by Nat Young, a former world surfing champion. Nat Young was severely beaten after a dispute that began as an argument over who had priority on a wave. These two images would help a non-surfer understand the stakes involved when surfers compete for waves. The waves themselves are an extraordinary resource lying at the centre of many surfers’ lives. The high value many surfers place on surfing means that competition for crowded waves can evoke strong emo- tions. At its worst, this competition can escalate to serious assaults such as that suffered by Nat Young. Surfing is no longer the idiosyncratic pursuit of a small counterculture. In fact, the popularity of surfing has exploded to the point where it is not only within the main- stream, it is big business. 1 And while the number of surfers continues to increase, * Law Clerk for Chief Judge William K. Sessions, III of the United States District Court for the District of Vermont. J.D. Yale Law School, 2004. I am grateful to Jeffrey Rachlinski, Robert Ellickson, An- thony Kronman, Oskar Liivak, Jason Byrne, Brian Fitzgerald and Carol Rose for comments and encour- agement. -

Surfing, Gender and Politics: Identity and Society in the History of South African Surfing Culture in the Twentieth-Century

Surfing, gender and politics: Identity and society in the history of South African surfing culture in the twentieth-century. by Glen Thompson Dissertation presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof. Albert M. Grundlingh Co-supervisor: Prof. Sandra S. Swart Marc 2015 0 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the author thereof (unless to the extent explicitly otherwise stated) and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: 8 October 2014 Copyright © 2015 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved 1 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract This study is a socio-cultural history of the sport of surfing from 1959 to the 2000s in South Africa. It critically engages with the “South African Surfing History Archive”, collected in the course of research, by focusing on two inter-related themes in contributing to a critical sports historiography in southern Africa. The first is how surfing in South Africa has come to be considered a white, male sport. The second is whether surfing is political. In addressing these topics the study considers the double whiteness of the Californian influences that shaped local surfing culture at “whites only” beaches during apartheid. The racialised nature of the sport can be found in the emergence of an amateur national surfing association in the mid-1960s and consolidated during the professionalisation of the sport in the mid-1970s.