I Am Prejudiced, and So Are You

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indecent by PAULA VOGEL Directed by WENDY C

McGuire Proscenium Stage / Feb 17 – Mar 24, 2018 Indecent by PAULA VOGEL directed by WENDY C. GOLDBERG PLAY GUIDE Inside THE PLAY Synopsis • 3 Characters and Setting • 4 Inspiration for Indecent • 5 Responses to Indecent • 6 Responses to The God of Vengeance • 7 THE PLAYWRIGHT On Paula Vogel • 8 Paula Vogel on Indecent • 9 Paula Vogel on Sholem Asch • 10-11 Glossary: Concepts, Words, Ideas • 12-15 ADDITIONAL INFORMATION For Further Reading and Understanding • 16 Play guides are made possible by Guthrie Theater Play Guide Copyright 2018 DRAMATURG Jo Holcomb GRAPHIC DESIGNER Akemi Graves CONTRIBUTORS Jo Holcomb Guthrie Theater, 818 South 2nd Street, Minneapolis, MN 55415 All rights reserved. With the exception of classroom use by teachers and individual personal use, no part of this Play Guide ADMINISTRATION 612.225.6000 may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic BOX OFFICE 612.377.2224 or 1.877.44.STAGE TOLL-FREE or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by an information storage and retrieval system, without permission in guthrietheater.org • Joseph Haj, artistic director writing from the publishers. Some materials published herein are written especially for our Guide. Others are reprinted by permission of their publishers. The Guthrie Theater receives support from the National The Guthrie creates transformative theater experiences that ignite the imagination, stir Endowment for the Arts. This activity is made possible in part by the Minnesota State Arts Board, through an appropriation the heart, open the mind, and build community through the illumination of our common by the Minnesota State Legislature. The Minnesota State Arts Board received additional funds to support this activity from humanity. -

The Radical Roots of the Alt-Right

Gale Primary Sources Start at the source. The Radical Roots of the Alt-Right Josh Vandiver Ball State University Various source media, Political Extremism and Radicalism in the Twentieth Century EMPOWER™ RESEARCH The radical political movement known as the Alt-Right Revolution, and Evolian Traditionalism – for an is, without question, a twenty-first century American audience. phenomenon.1 As the hipster-esque ‘alt’ prefix 3. A refined and intensified gender politics, a suggests, the movement aspires to offer a youthful form of ‘ultra-masculinism.’ alternative to conservatism or the Establishment Right, a clean break and a fresh start for the new century and .2 the Millennial and ‘Z’ generations While the first has long been a feature of American political life (albeit a highly marginal one), and the second has been paralleled elsewhere on the Unlike earlier radical right movements, the Alt-Right transnational right, together the three make for an operates natively within the political medium of late unusual fusion. modernity – cyberspace – because it emerged within that medium and has been continuously shaped by its ongoing development. This operational innovation will Seminal Alt-Right figures, such as Andrew Anglin,4 continue to have far-reaching and unpredictable Richard Spencer,5 and Greg Johnson,6 have been active effects, but researchers should take care to precisely for less than a decade. While none has continuously delineate the Alt-Right’s broader uniqueness. designated the movement as ‘Alt-Right’ (including Investigating the Alt-Right’s incipient ideology – the Spencer, who coined the term), each has consistently ferment of political discourses, images, and ideas with returned to it as demarcating the ideological territory which it seeks to define itself – one finds numerous they share. -

Printed Covers Sailing Through the Air As Their Tables Are REVIEWS and REFUTATIONS Ipped

42 RECOMMENDED READING Articles Apoliteic music: Neo-Folk, Martial Industrial and metapolitical fascism by An- ton Shekhovtsov Former ELF/Green Scare Prisoner Exile Now a Fascist by NYC Antifa Books n ٻThe Nature of Fascism by Roger Gri Modernism and Fascism: The Sense of a Beginning under Mussolini and Hitler by Roger n ٻGri n ٻFascism edited by Roger Gri Black Sun: Aryan Cults, Esoteric Nazism, and the Politics of Identity by Nicholas Go- A FIELD GUIDE TO STRAW MEN odrick-Clarke Gods of the Blood: The Pagan Revival and White Separatism by Mattias Gardell Modernity and the Holocaust by Zygmunt Bauman Sadie and Exile, Esoteric Fascism, and Exterminate All the Brutes by Sven Lindqvist Confronting Fascism: Discussion Documents for a Militant Movement by Don Hamerquist, Olympias Little White Lies J. Sakai, Anti-Racist Action Chicago, and Mark Salotte Baedan: A Journal of Queer Nihilism Baedan 2: A Queer Journal of Heresy Baedan 3: A Journal of Queer Time Travel Against His-story, Against Leviathan! by Fredy Perlman Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body, and Primitive Accumulation by Silvia Federici Witchcraft and the Gay Counterculture by Arthur Evans The Many-Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners, and the Hidden History of the Revo- lutionary Atlantic by Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker Gone to Croatan: Origins of North American Dropout Culture edited by Ron Sakolsky and James Koehnline The Subversion of Politics: European Autonomous Social Movements and the Decolonization of Everyday Life by Georgy Katsia cas 1312 committee // February 2016 How the Irish Became White by Noel Ignatiev How Deep is Deep Ecology? by George Bradford Against the Megamachine: Essays on Empire and Its Enemies by David Watson Elements of Refusal by John Zerzan Against Civilization edited by John Zerzan This World We Must Leave and Other Essays by Jacques Camatte 41 total resistance mounted to the advent of industrial society. -

The Culture of Wikipedia

Good Faith Collaboration: The Culture of Wikipedia Good Faith Collaboration The Culture of Wikipedia Joseph Michael Reagle Jr. Foreword by Lawrence Lessig The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. Web edition, Copyright © 2011 by Joseph Michael Reagle Jr. CC-NC-SA 3.0 Purchase at Amazon.com | Barnes and Noble | IndieBound | MIT Press Wikipedia's style of collaborative production has been lauded, lambasted, and satirized. Despite unease over its implications for the character (and quality) of knowledge, Wikipedia has brought us closer than ever to a realization of the centuries-old Author Bio & Research Blog pursuit of a universal encyclopedia. Good Faith Collaboration: The Culture of Wikipedia is a rich ethnographic portrayal of Wikipedia's historical roots, collaborative culture, and much debated legacy. Foreword Preface to the Web Edition Praise for Good Faith Collaboration Preface Extended Table of Contents "Reagle offers a compelling case that Wikipedia's most fascinating and unprecedented aspect isn't the encyclopedia itself — rather, it's the collaborative culture that underpins it: brawling, self-reflexive, funny, serious, and full-tilt committed to the 1. Nazis and Norms project, even if it means setting aside personal differences. Reagle's position as a scholar and a member of the community 2. The Pursuit of the Universal makes him uniquely situated to describe this culture." —Cory Doctorow , Boing Boing Encyclopedia "Reagle provides ample data regarding the everyday practices and cultural norms of the community which collaborates to 3. Good Faith Collaboration produce Wikipedia. His rich research and nuanced appreciation of the complexities of cultural digital media research are 4. The Puzzle of Openness well presented. -

Al-QAEDA and the ARYAN NATIONS

Al-QAEDA AND THE ARYAN NATIONS A FOUCAULDIAN PERSPECTIVE by HUNTER ROSS DELL Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN CRIMINOLOGY AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON DECEMBER 2006 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS For my parents, Charles and Virginia Dell, without whose patience and loving support, I would not be who or where I am today. November 10, 2006 ii ABSTRACT AL-QAEDA AND THE ARYAN NATIONS A FOUCALTIAN PERSPECTIVE Publication No. ______ Hunter Ross Dell, M.A. The University of Texas at Arlington, 2006 Supervising Professor: Alejandro del Carmen Using Foucauldian qualitative research methods, this study will compare al- Qaeda and the Aryan Nations for similarities while attempting to uncover new insights from preexisting information. Little or no research had been conducted comparing these two organizations. The underlying theory is that these two organizations share similar rhetoric, enemies and goals and that these similarities will have implications in the fields of politics, law enforcement, education, research and United States national security. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS......................................................................................... ii ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................ iii Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION...................................................................................... -

Computational Propaganda, Jewish-Americans and the 2018 Midterms

A report from the Center on Technology and Society OCT 2018 Computational Propaganda, Jewish-Americans and the 2018 Midterms: The Amplification of Anti-Semitic Harassment Online Our Mission: To stop the defamation of the Jewish people and to secure justice and fair treatment to all. ABOUT CENTER FOR TECHNOLOGY & SOCIETY AND THE BELFER FELLOWS In a world riddled with cyberhate, online harassment, and misuses of ADL (Anti-Defamation technology, the Center for Technology & Society (CTS) serves as a resource League) fights anti-Semitism to tech platforms and develops proactive solutions. Launched in 2017 and and promotes justice for all. headquartered in Silicon Valley, CTS aims for global impacts and applications in an increasingly borderless space. It is a force for innovation, producing Join ADL to give a voice to cutting-edge research to enable online civility, protect vulnerable populations, those without one and to support digital citizenship, and engage youth. CTS builds on ADL’s century of protect our civil rights. experience building a world without hate and supplies the tools to make that a possibility both online and off-line. Learn more: adl.org The Belfer Fellowship program supports CTS’s efforts to create innovative solutions to counter online hate and ensure justice and fair treatment for all in the digital age through fellowships in research and outreach projects. The program is made possible by a generous contribution from the Robert A. and Renée E. Belfer Family Foundation. The inaugural 2018-2019 Fellows are: • Rev. Dr. Patricia Novick, Ph.D., of the Multicultural Leadership Academy, a program that brings Latino and African-American leaders together. -

The Fringe Insurgency Connectivity, Convergence and Mainstreaming of the Extreme Right

The Fringe Insurgency Connectivity, Convergence and Mainstreaming of the Extreme Right Jacob Davey Julia Ebner About this paper About the authors This report maps the ecosystem of the burgeoning Jacob Davey is a Researcher and Project Coordinator at ‘new’ extreme right across Europe and the US, which is the Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD), overseeing the characterised by its international outlook, technological development and delivery of a range of online counter- sophistication, and overtures to groups outside of the extremism initiatives. His research interests include the traditional recruitment pool for the extreme-right. This role of communications technologies in intercommunal movement is marked by its opportunistic pragmatism, conflict, the use of internet culture in information seeing movements which hold seemingly contradictory operations, and the extreme-right globally. He has ideologies share a bed for the sake of achieving provided commentary on the extreme right in a range common goals. It examines points of connectivity of media sources including The Guardian, The New York and collaboration between disparate groups and Times and the BBC. assesses the interplay between different extreme-right movements, key influencers and subcultures both Julia Ebner is a Research Fellow at the Institute for online and offline. Strategic Dialogue (ISD) and author of The Rage: The Vicious Circle of Islamist and Far-Right Extremism. Her research focuses on extreme right-wing mobilisation strategies, cumulative extremism and European terrorism prevention initiatives. She advises policy makers and tech industry leaders, regularly writes for The Guardian and The Independent and provides commentary on broadcast media, including the BBC and CNN. © ISD, 2017 London Washington DC Beirut Toronto This material is offered free of charge for personal and non-commercial use, provided the source is acknowledged. -

Qanon and Facebook

The Boom Before the Ban: QAnon and Facebook Ciaran O’Connor, Cooper Gatewood, Kendrick McDonald and Sarah Brandt 2 ‘THE GREAT REPLACEMENT’: THE VIOLENT CONSEQUENCES OF MAINSTREAMED EXTREMISM / Document title: About this report About NewsGuard This report is a collaboration between the Institute Launched in March 2018 by media entrepreneur and for Strategic Dialogue (ISD) and the nonpartisan award-winning journalist Steven Brill and former Wall news-rating organisation NewsGuard. It analyses Street Journal publisher Gordon Crovitz, NewsGuard QAnon-related contents on Facebook during a provides credibility ratings and detailed “Nutrition period of increased activity, just before the platform Labels” for thousands of news and information websites. implemented moderation of public contents spreading NewsGuard rates all the news and information websites the conspiracy theory. Combining quantitative and that account for 95% of online engagement across the qualitative analysis, this report looks at key trends in US, UK, Germany, France, and Italy. NewsGuard products discussions around QAnon, prominent accounts in that include NewsGuard, HealthGuard, and BrandGuard, discussion, and domains – particularly news websites which helps marketers concerned about their brand – that were frequently shared alongside QAnon safety, and the Misinformation Fingerprints catalogue of contents on Facebook. This report also recommends top hoaxes. some steps to be taken by technology companies, governments and the media when seeking to counter NewsGuard rates each site based on nine apolitical the spread of problematic conspiracy theories like criteria of journalistic practice, including whether a QAnon on social media. site repeatedly publishes false content, whether it regularly corrects or clarifies errors, and whether it avoids deceptive headlines. -

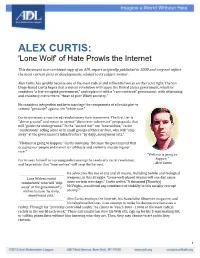

ALEX CURTIS: 'Lone Wolf' of Hate Prowls the Internet

ALEX CURTIS: 'Lone Wolf' of Hate Prowls the Internet This document is an archived copy of an ADL report originally published in 2000 and may not reflect the most current facts or developments related to its subject matter. Alex Curtis has quickly become one of the most radical and influential voices on the racist right. The San Diego‐based Curtis hopes that a violent revolution will topple the United States government, which he considers "a Jew‐occupied government," and replace it with a "race‐centered" government, with citizenship and residency restricted to "those of pure White ancestry." He considers integration and intermarriage the components of a Jewish plot to commit "genocide" against the "white race." Curtis envisions a two‐tiered revolutionary hate movement. The first tier is "above ground" and meant to spread "divisive or subversive" propaganda that will "guide the underground." In the "second tier" are "lone wolves," racist "combatants" acting alone or in small groups of three or four, who will "chip away" at the government's infrastructure "by daily, anonymous acts." "Violence is going to happen," Curtis contends, "because the government that occupies our people and nation is ruthlessly and violently murdering our race." "Violence is going to Curtis sees himself as a propagandist sowing the seeds of a racist revolution, happen," and he predicts that "lone wolves" will reap the harvest. ‐ Alex Curtis He advocates the use of any and all means, including bombs and biological Lone Wolves: racist weapons, in this struggle. "Some well‐placed Aryans will one day cause 'combatants' who will 'chip some serious wreckage," Curtis writes."A thousand [Timothy] away' at the government's McVeighs...would end any semblance of stability in this racially‐corrupt infrastructure 'by daily, society." anonymous acts.' Alex Curtis employs the Internet, his Nationalist Observer magazine, and his telephone hotlines in an attempt to make his destructive fantasies a reality. -

Post-Digital Cultures of the Far Right

Maik Fielitz, Nick Thurston (eds.) Post-Digital Cultures of the Far Right Political Science | Volume 71 Maik Fielitz, Nick Thurston (eds.) Post-Digital Cultures of the Far Right Online Actions and Offline Consequences in Europe and the US With kind support of Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Na- tionalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No- Derivatives 4.0 (BY-NC-ND) which means that the text may be used for non-commer- cial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ To create an adaptation, translation, or derivative of the original work and for com- mercial use, further permission is required and can be obtained by contacting [email protected] Creative Commons license terms for re-use do not apply to any content (such as graphs, figures, photos, excerpts, etc.) not original to the Open Access publication and further permission may be required from the rights holder. The obligation to research and clear permission lies solely with the party re-using the material. © 2019 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld Cover layout: Kordula Röckenhaus, Bielefeld Typeset by Alexander Masch, Bielefeld Printed by Majuskel Medienproduktion GmbH, Wetzlar Print-ISBN 978-3-8376-4670-2 PDF-ISBN 978-3-8394-4670-6 https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839446706 Contents Introduction | 7 Stephen Albrecht, Maik Fielitz and Nick Thurston ANALYZING Understanding the Alt-Right. -

Downloaded Cc-By License from Brill.Com09/30/2021At the Time of 05:35:12PM Publication

Fascism 10 (2021) 166-185 ‘The Girl Who Was Chased by Fire’: Violence and Passion in Contemporary Swedish Fascist Fiction Mattias Gardell Centre for Multidisciplinary Studies of Racism, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden [email protected] Abstract Fascism invites its adherents to be part of something greater than themselves, invoking their longing for honor and glory, passion and heroism. An important avenue for articulating its affective dimension is cultural production. This article investigates the role of violence and passion in contemporary Swedish-language fascist fiction. The protagonist is typically a young white man or woman who wakes up to the realities of the ongoing white genocide through being exposed to violent crime committed by racialized aliens protected by the System. Seeking revenge, the protagonist learns how to be a man or meets her hero, and is introduced to fascist ideology and the art of killing. Fascist literature identifies aggression and ethnical cleansing as altruistic acts of love. With its passionate celebration of violence, fascism hails the productivity of destructivity, and the life-bequeathing aspects of death, which is at the core of fascism’s urge for national rebirth. Keywords Sweden – fascist culture – fascist fiction – violence – heroism – death – love – radical nationalism Fascism – here used in its Griffian sense as a generic term for revolutionary nationalisms centered on a mythic core of national rebirth – has a discernible affective dimension. It offers its adherents to be part of something greater than themselves, invoking their longing for glory, honor, and beauty, and inducing their capacities for hate, love, self-sacrifice, and violence. An important avenue © Mattias Gardell, 2021 | doi:10.1163/22116257-10010004 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the prevailingDownloaded cc-by license from Brill.com09/30/2021at the time of 05:35:12PM publication. -

Into the Storm Uncovering the Narrative of Qanon

Into the storm Uncovering the narrative of QAnon Ioana Frincu (s1904914) University of Twente BSc. Communication Science Supervisor Menno de Jong “I think that the people who approach the social sciences with a ready-made conspiracy theory thereby deny themselves the possibility of ever understanding what the task of the social sciences is, for they assume that we can explain practically everything in society by asking who wanted it, whereas the real task of the social sciences is to explain those things which nobody wants, such as, for example, a war, or a depression“ (Popper, 2002, p. 168) 1 Abstract The alarming growth of QAnon, a conspiracy theory group, is just the tip of an complex issue which is dividing the world. From conspiracy theories shared on internet to storming Capitol Hill and disrupting the public and political discourse, QAnon quickly become a major threat in the real world. Nevertheless, there is still a limited understanding of its anatomy, characteristic and who are the followers, especially within academia. To address the gap, I will attempt to uncover the narrative of QAnon and its characteristics as the main focus of this research. Conducting a content analysis on 6, 432 posts from Q drops, 8kun, r/QAnon_Casualties and r/Qult_Headquarters implies taking into consideration two opposite perspective: the QAnon insider view and the outsider perspective that takes an anti-QAnon stand. The results are pointing out to an engaging “good vs evil” fight behind the movement as well as cult behavior and a goal to discredit any authority, among others. The conclusion contains several unexplored paths for future research and practical advice to the public and institutions about how to make sense of QAnon.