Policy in Ireland Was to Bring to an End the Tributary Relationship Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Irish Historic Towns Atlas (IHTA), No. 20, Tuam Author

Digital content from: Irish Historic Towns Atlas (IHTA), no. 20, Tuam Author: J.A. Claffey Editors: Anngret Simms, H.B. Clarke, Raymond Gillespie, Jacinta Prunty Consultant editor: J.H. Andrews Cartographic editor: Sarah Gearty Editorial assistants: Angela Murphy, Angela Byrne, Jennnifer Moore Printed and published in 2009 by the Royal Irish Academy, 19 Dawson Street, Dublin 2 Maps prepared in association with the Ordnance Survey Ireland and Land and Property Services Northern Ireland The contents of this digital edition of Irish Historic Towns Atlas no. 20, Tuam, is registered under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International License. Referencing the digital edition Please ensure that you acknowledge this resource, crediting this pdf following this example: Topographical information. In J.A. Claffey, Irish Historic Towns Atlas, no. 20, Tuam. Royal Irish Academy, Dublin, 2009 (www.ihta.ie, accessed 4 February 2016), text, pp 1–20. Acknowledgements (digital edition) Digitisation: Eneclann Ltd Digital editor: Anne Rosenbusch Original copyright: Royal Irish Academy Irish Historic Towns Atlas Digital Working Group: Sarah Gearty, Keith Lilley, Jennifer Moore, Rachel Murphy, Paul Walsh, Jacinta Prunty Digital Repository of Ireland: Rebecca Grant Royal Irish Academy IT Department: Wayne Aherne, Derek Cosgrave For further information, please visit www.ihta.ie TUAM View of R.C. cathedral, looking west, 1843 (Hall, iii, p. 413) TUAM Tuam is situated on the carboniferous limestone plain of north Galway, a the turbulent Viking Age8 and lends credence to the local tradition that ‘the westward extension of the central plain. It takes its name from a Bronze Age Danes’ plundered Tuam.9 Although the well has disappeared, the site is partly burial mound originally known as Tuaim dá Gualann. -

A Brief History of Christ Church MEDIEVAL PERIOD

A Brief History of Christ Church MEDIEVAL PERIOD Christ Church was founded in 1546, and there had been a college here since 1525, but prior to the Dissolution of the monasteries, the site was occupied by a priory dedicated to the memory of St Frideswide, the patron saint of both university and city. St Frideswide, a noble Saxon lady, founded a nunnery for herself as head and for twelve more noble virgin ladies sometime towards the end of the seventh century. She was, however, pursued by Algar, prince of Leicester, for her hand in marriage. She refused his frequent approaches which became more and more desperate. Frideswide and her ladies, forewarned miraculously of yet another attempt by Algar, fled up river to hide. She stayed away some years, settling at Binsey, where she performed healing miracles. On returning to Oxford, Frideswide found that Algar was as persistent as ever, laying siege to the town in order to capture his bride. Frideswide called down blindness on Algar who eventually repented of his ways, and left Frideswide to her devotions. Frideswide died in about 737, and was canonised in 1480. Long before this, though, pilgrims came to her shrine in the priory church which was now populated by Augustinian canons. Nothing remains of Frideswide’s nunnery, and little - just a few stones - of the Saxon church but the cathedral and the buildings around the cloister are the oldest on the site. Her story is pictured in cartoon form by Burne-Jones in one of the windows in the cathedral. One of the gifts made to the priory was the meadow between Christ Church and the Thames and Cherwell rivers; Lady Montacute gave the land to maintain her chantry which lay in the Lady Chapel close to St Frideswide’s shrine. -

Scouting Games. 61 Horse and Rider 54 1

The MacScouter's Big Book of Games Volume 2: Games for Older Scouts Compiled by Gary Hendra and Gary Yerkes www.macscouter.com/Games Table of Contents Title Page Title Page Introduction 1 Radio Isotope 11 Introduction to Camp Games for Older Rat Trap Race 12 Scouts 1 Reactor Transporter 12 Tripod Lashing 12 Camp Games for Older Scouts 2 Map Symbol Relay 12 Flying Saucer Kim's 2 Height Measuring 12 Pack Relay 2 Nature Kim's Game 12 Sloppy Camp 2 Bombing The Camp 13 Tent Pitching 2 Invisible Kim's 13 Tent Strik'n Contest 2 Kim's Game 13 Remote Clove Hitch 3 Candle Relay 13 Compass Course 3 Lifeline Relay 13 Compass Facing 3 Spoon Race 14 Map Orienteering 3 Wet T-Shirt Relay 14 Flapjack Flipping 3 Capture The Flag 14 Bow Saw Relay 3 Crossing The Gap 14 Match Lighting 4 Scavenger Hunt Games 15 String Burning Race 4 Scouting Scavenger Hunt 15 Water Boiling Race 4 Demonstrations 15 Bandage Relay 4 Space Age Technology 16 Firemans Drag Relay 4 Machines 16 Stretcher Race 4 Camera 16 Two-Man Carry Race 5 One is One 16 British Bulldog 5 Sensational 16 Catch Ten 5 One Square 16 Caterpillar Race 5 Tape Recorder 17 Crows And Cranes 5 Elephant Roll 6 Water Games 18 Granny's Footsteps 6 A Little Inconvenience 18 Guard The Fort 6 Slash hike 18 Hit The Can 6 Monster Relay 18 Island Hopping 6 Save the Insulin 19 Jack's Alive 7 Marathon Obstacle Race 19 Jump The Shot 7 Punctured Drum 19 Lassoing The Steer 7 Floating Fire Bombardment 19 Luck Relay 7 Mystery Meal 19 Pocket Rope 7 Operation Neptune 19 Ring On A String 8 Pyjama Relay 20 Shoot The Gap 8 Candle -

Proquest Dissertations

UNIVERSITY D'OTTAWA - ECOLE UES GRADUES EFFORTS IN THE FIELD OF RELIGIOUS TOLERATION IN THE EARLY POLITICAL CAREER OF EDMUND BURKE, I765-I782 by John Edmund O'Brien Thesis presented to the Faculty of Arts of the University of Ottawa through the Department of History as partial fulfill ment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. -sit>tee d'd'o0( ^ <^ "*YJ ^ \ s* m Ottawa v y t , L.ttKAKicS » Ottawa, Canada, 1955 UNIVERSITY OF OTTAWA - SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES UMI Number: DC53435 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI UMI Microform DC53435 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 _ UN1VERSITE D'OTTAWA - ECOLE PES GRADUES ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis was prepared under the guidance of Doctor George Buxton of the department of History of the University of Ottawa. ; ; The writer wishes to express his gratitude to the ; I j I following people or institutions that helped in the work of i ithe thesis: to Doctor Ross Hoffman and Doctor Paul Levack of i the Graduate School of Fordham University for introducing the! writer to the field of Burke studies; to Earl Fitzwilliam and; i his trustees for permission to quote from Burke letters in ! i the Wentworth Manuscripts and to J. -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details ‘Providence and Political Economy’: Josiah Tucker’s Providential Argument for Free Trade Peter Xavier Price PhD Thesis in Intellectual History University of Sussex April 2016 2 University of Sussex Peter Xavier Price Submitted for the award of a PhD in Intellectual History ‘Providence and Political Economy’: Josiah Tucker’s Providential Argument for Free Trade Thesis Summary Josiah Tucker, who was the Anglican Dean of Gloucester from 1758 until his death in 1799, is best known as a political pamphleteer, controversialist and political economist. Regularly called upon by Britain’s leading statesmen, and most significantly the Younger Pitt, to advise them on the best course of British economic development, in a large variety of writings he speculated on the consequences of North American independence for the global economy and for international relations; upon the complicated relations between small and large states; and on the related issue of whether low wage costs in poor countries might always erode the competitive advantage of richer nations, thereby establishing perpetual cycles of rise and decline. -

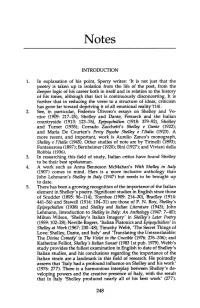

INTRODUCTION 1. in Explanation of His Point, Sperry Writes: 'It Is Not Just

Notes INTRODUCTION 1. In explanation of his point, Sperry writes: 'It is not just that the poetry is taken up in isolation from the life of the poet, from the deeper logic of his career both in itself and in relation to the history of his times, although that fact is continuously disconcerting. It is further that in reducing the verse to a structure of ideas, criticism has gone far toward depriving it of all emotional reality'(14). 2. See, in particular, Federico Olivero's essays on Shelley and Ve nice (1909: 217-25), Shelley and Dante, Petrarch and the Italian countryside (1913: 123-76), Epipsychidion (1918: 379-92), Shelley and Turner (1935); Corrado Zacchetti's Shelley e Dante (1922); and Maria De Courten's Percy Bysshe Shelley e l'Italia (1923). A more recent, and important, work is Aurelio Zanco's monograph, Shelley e l'Italia (1945). Other studies of note are by Tirinelli (1893); Fontanarosa (1897); Bernheimer (1920); Bini (1927); and Viviani della Robbia (1936). 3. In researching this field of study, Italian critics have found Shelley to be their best spokesman. 4. A work such as Anna Benneson McMahan's With Shelley in Italy (1907) comes to mind. Hers is a more inclusive anthology than John Lehmann's Shelley in Italy (1947) but needs to be brought up to date. 5. There has been a growing recognition of the importance of the Italian element in Shelley's poetry. Significant studies in English since those of Scudder (1895: 96-114), Toynbee (1909: 214-30), Bradley (1914: 441-56) and Stawell (1914: 104-31) are those of P. -

Ordination Sermons: a Bibliography1

Ordination Sermons: A Bibliography1 Aikman, J. Logan. The Waiting Islands an Address to the Rev. George Alexander Tuner, M.B., C.M. on His Ordination as a Missionary to Samoa. Glasgow: George Gallie.. [etc.], 1868. CCC. The Waiting Islands an Address to the Rev. George Alexander Tuner, M.B., C.M. on His Ordination as a Missionary to Samoa. Glasgow: George Gallie.. [etc.], 1868. Aitken, James. The Church of the Living God Sermon and Charge at an Ordination of Ruling Elders, 22nd June 1884. Edinburgh: Robert Somerville.. [etc.], 1884. Allen, William. The Minister's Warfare and Weapons a Sermon Preached at the Installation of Rev. Seneca White at Wiscasset, April 18, 1832. Brunswick [Me.]: Press of Joseph Grif- fin, 1832. Allen, Willoughby C. The Christian Hope. London: John Murray, 1917. Ames, William, Dan Taylor, William Thompson, of Boston, and Benjamin. Worship. The Re- spective Duties of Ministers and People Briefly Explained and Enforced the Substance of Two Discourses, Delivered at Great-Yarmouth, in Norfolk, Jan. 9th, 1775, at the Ordina- tion of the Rev. Mr. Benjamin Worship, to the Pastoral Office. Leeds: Printed by Griffith Wright, 1775. Another brother. A Sermon Preach't at a Publick Ordination in a Country Congregation, on Acts XIII. 2, 3. Together with an Exhortation to the Minister and People. London: Printed for John Lawrance.., 1697. Appleton, Nathaniel, and American Imprint Collection (Library of Congress). How God Wills the Salvation of All Men, and Their Coming to the Knowledge of the Truth as the Means Thereof Illustrated in a Sermon from I Tim. II, 4 Preached in Boston, March 27, 1753 at the Ordination of the Rev. -

The Great Fraud of Ulster

^i.: J <. •->.w.: >,%<.> ^ S. * f»*. ^- -:; 'I -f4.... 4 t/^ :S: >.t <» Iv.vO "*^^^- srr. T^:^ ,1 , c-<^ 6 1j^-r4 "^*^^t r %. , e-- THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY H Z^g- Crf». 2 REMOTE STOiMGE Return this book on or before the Latest Date stamped below. University of Illinois Library H0^i8\9» 19(ft SEP 1 4 I )97 L161 — H41 —— ——— — Ul s REMOTE STORAGE H34f % "STOLEN WATERS." ^^^ '^X J ^ j 80ME PRESS NOTICES. »\ "We can welcome Mr. Ilealy's treatment of a difficult and obscure J!N episode in the hiatory of Ulster as on the whole impartial, and based on Qr; a judicial reading of a vast accumulation of documentary evidence. m; In his capacity as historical detective he is fair-minded to a degree, T.'hich w'Mild amaze us if we were not so well acquainted with the well- tempered quality of an intellect that for subtlety and power and a dis- passionate coolness is not surpassed by that of any Irishman living. The wonderful net of intrigue by which all this was contrived has been carefully unravelled by Mr. llealy with a pertinaceous ingenuity worthy of Sherlock -Holmes." Morning I'ost. " Mr. Ilealy has accomi)lished a difficult task with considerable success. The result of his labours is an absorbing book. The author has succeeded in weaving a ivjmantic story out of the dry material of official records and legal documents." Athcnceum. " The story that Mr. Healy tells has something of the flavour of historical romance. Mr. Ilealy's method of argument on the main issue is calm and temperate. -

Ulster-Scots

Ulster-Scots Biographies 2 Contents 1 Introduction The ‘founding fathers’ of the Ulster-Scots Sir Hugh Montgomery (1560-1636) 2 Sir James Hamilton (1559-1644) Major landowning families The Colvilles 3 The Stewarts The Blackwoods The Montgomerys Lady Elizabeth Montgomery 4 Hugh Montgomery, 2nd Viscount Sir James Montgomery of Rosemount Lady Jean Alexander/Montgomery William Montgomery of Rosemount Notable individuals and families Patrick Montgomery 5 The Shaws The Coopers James Traill David Boyd The Ross family Bishops and ministers Robert Blair 6 Robert Cunningham Robert Echlin James Hamilton Henry Leslie John Livingstone David McGill John MacLellan 7 Researching your Ulster-Scots roots www.northdowntourism.com www.visitstrangfordlough.co.uk This publication sets out biographies of some of the part. Anyone interested in researching their roots in 3 most prominent individuals in the early Ulster-Scots the region may refer to the short guide included at story of the Ards and north Down. It is not intended to section 7. The guide is also available to download at be a comprehensive record of all those who played a northdowntourism.com and visitstrangfordlough.co.uk Contents Montgomery A2 Estate boundaries McLellan Anderson approximate. Austin Dunlop Kyle Blackwood McDowell Kyle Kennedy Hamilton Wilson McMillin Hamilton Stevenson Murray Aicken A2 Belfast Road Adams Ross Pollock Hamilton Cunningham Nesbit Reynolds Stevenson Stennors Allen Harper Bayly Kennedy HAMILTON Hamilton WatsonBangor to A21 Boyd Montgomery Frazer Gibson Moore Cunningham -

International Spy Museum

International Spy Museum Searchable Master Script, includes all sections and areas Area Location, ID, Description Labels, captions, and other explanatory text Area 1 – Museum Lobby M1.0.0.0 ΚΑΤΆΣΚΟΠΟΣ SPY SPION SPIJUN İSPİYON SZPIEG SPIA SPION ESPION ESPÍA ШПИОН Language of Espionage, printed on SCHPION MAJASUSI windows around entrance doors P1.1.0.0 Visitor Mission Statement For Your Eyes Only For Your Eyes Only Entry beyond this point is on a need-to-know basis. Who needs to know? All who would understand the world. All who would glimpse the unseen hands that touch our lives. You will learn the secrets of tradecraft – the tools and techniques that influence battles and sway governments. You will uncover extraordinary stories hidden behind the headlines. You will meet men and women living by their wits, lurking in the shadows of world affairs. More important, however, are the people you will not meet. The most successful spies are the unknown spies who remain undetected. Our task is to judge their craft, not their politics – their skill, not their loyalty. Our mission is to understand these daring professionals and their fallen comrades, to recognize their ingenuity and imagination. Our goal is to see past their maze of mirrors and deception to understand their world of intrigue. Intelligence facts written on glass How old is spying? First record of spying: 1800 BC, clay tablet from Hammurabi regarding his spies. panel on left side of lobby First manual on spy tactics written: Over 2,000 years ago, Sun Tzu’s The Art of War. 6 video screens behind glass panel with facts and images. -

Food Security in Ancestral Tewa Coalescent Communities: the Zooarchaeology of Sapa'owingeh in the Northern Rio Grande, New Mexico

Southern Methodist University SMU Scholar Anthropology Theses and Dissertations Anthropology Spring 5-15-2021 Food Security in Ancestral Tewa Coalescent Communities: The Zooarchaeology of Sapa'owingeh in the Northern Rio Grande, New Mexico Rachel Burger [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/hum_sci_anthropology_etds Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Burger, Rachel, "Food Security in Ancestral Tewa Coalescent Communities: The Zooarchaeology of Sapa'owingeh in the Northern Rio Grande, New Mexico" (2021). Anthropology Theses and Dissertations. https://scholar.smu.edu/hum_sci_anthropology_etds/13 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Anthropology at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. FOOD SECURITY IN ANCESTRAL TEWA COALESCENT COMMUNITIES: THE ZOOARCHAEOLOGY OF SAPA’OWINGEH IN THE NORTHERN RIO GRANDE, NEW MEXICO Approved by: ___________________________________ B. Sunday Eiselt, Associate Professor Southern Methodist University ___________________________________ Samuel G. Duwe, Assistant Professor University of Oklahoma ___________________________________ Karen D. Lupo, Professor Southern Methodist University ___________________________________ Christopher I. Roos, Professor Southern Methodist University FOOD SECURITY IN ANCESTRAL TEWA COALESCENT COMMUNITIES: THE ZOOARCHAEOLOGY OF SAPA’OWINGEH IN THE NORTHERN RIO GRANDE, NEW MEXICO A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the Dedman College Southern Methodist University in Partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a Major in Anthropology by Rachel M. Burger B.A. Anthropology and Archaeology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville M.A., Anthropology, Southern Methodist University May 15, 2021 Copyright (2021) Rachel M. -

Grattan's Parliament

REMINISCENCES OF GRATTAN’S PARLIAMENT AND THE IRISH LAND QUESTION. BY O. C. DALHOUSIE ROSS, M.I.C.E., M. ROYAL AGRICULTURAL SOCIETY. “ There lies beneath the whole of the Irish question that fearful Land .question, “ which has troubled all Administrations in Ireland during the last 100 years, and which “ will not be settled by settling the question of the National Government. How “ do Mr. Morley and the enthusiastic advocates of Home Rule think they can settle “ these Irish land difficulties which have so long been at the root of the Irish question? “ Irish laws could not multiply the number of Irish acres to be distributed among the “ Irish people ; Irish laws could not increase the fertility of the soil. While you may “ attempt to gratify what you may call the political or national aspirations of Ireland, “ you will leave the land still in question—Me land difficulties which arc insoluble by “ any methods which arc at present proposed."—Speech at Newcastle, June 22nd, 1886, of the Right Honourable Georgia G o s c h e n , M .P . Reprinted from “ Fair-Trade ♦ PUBLISHED BY GEORGE REVEIRS, GRAYSTOKE PLACE, FETTER LANE, LONDON, E.C. PRICE TWOPENCE. SKETCH MAP OF IRELAND, Showing the only districts which were represented previous to the X V IItli Century in the Irish Parliament, viz., Dublin and Drogheda, Wexford, Waterford, and Cork. REMINISCENCES OF GRATTAN’S PARLIAMENT AND THE IRISH LAND QUESTION. ------M------ I n the “ Personal Sketches of his Own Time,” published some sixty years ago by a certain learned knight and Irish judge, a lively account is given of some of the most distinguished members of Grattan’s Parlia ment, and of the social condition of Ireland in the days immediately preceding the Union with Great Britain in the year 1800; and some gleanings from that now forgotten publication may be of interest at this moment, whilst serving as a plea for a few observations on the Irish land question.