Preventing Future Children from Living in Poverty in Port Isabel, Texas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2011 Program

2 x Rio Grande Valley Sports Hall of Fame I welcome you to the 24th Annual Rio Grande Valley Sports Hall of Fame Induction Banquet. We are happy to have the banquet return to Brownsville, after having been in McAllen and Donna for the past four years. Brownsville hosted the two largest crowds of our banquet history in 2005 and 2006 with attendance of 360 guests. With the outstanding Class of 2011 being honored tonight, the attendance should surpass 300 again! I offer my congratulations to the 2011 class of seven inductees! As is usually the case, football again dominates the class that was selected by 85 voters from the group of past inductees and Hall of Fame board members, who took time to study the biographies and submit their votes last September. Six of the seven new inductees were outstanding football players representing their high schools. Two of them (Bob Brumley and Sammy Garza) went on to play professional football after highly successful collegiate careers. Another (Travis Sanders) still holds a 33-year old consecutive 100-yard rushing record for the Valley. All-State quarterback & safety (Donald Guillot) went on to NCAA baseball stardom at the University of Texas-PanAmerican, while the football coach of the class (Bruce Bush) has a stellar record of 41 successful seasons in South Texas. Another former quarterback from the state semi-finalist PSJA Bears (Carlos Vela) became a well-known trackand& field coach in the Valley. In addition, not to be outdone is the man (Ronnie Zamora) who helps players and coaches of several sports gain local, state and national recognition with his sports media writing, announcing and website work, always bringing recognition for others to the Valley. -

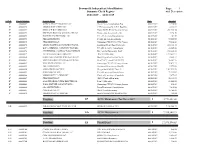

BR: Summary Check Register with Desc 06042015

Brownsville Independent School District Page: 1 Summary Check Register with Description 08/01/2019 - 08/31/2019 FUND Check Number Vendor Name Description Date Amount E7 00000069 MARCO ARIZPE ROOFING LLC. Sharp Elem.-Consolidation Proj 08/08/2019 1,350.00 E7 00000070 ARMKO INDUSTRIES INC. CTE Cummings-BLA H.S. Roof Re- 08/09/2019 4,886.82 E7 00000071 GERLACH BUILDERS LLC. Hanna ECHS HVAC System & Contr 08/09/2019 496,730.94 E7 00000072 GREEN-RUBIANO & ASSOCIATES INC Engineering Assessment of the 08/09/2019 5,194.50 E7 00000073 CARRIER ENTERPRISES LLC. Perez Elementary-Consolidation 08/12/2019 101.79 E7 00000074 PBK ARCHITECTS Facility Interior Assessments 08/12/2019 87,500.00 E7 00000075 CPM DESIGN LLC. Cummings CTE CV4 & CV3 Classro 08/16/2019 75,816.86 E7 00000076 ARGIO ROOFING & CONSTRUCTION L Southmost Elem. Roof Replaceme 08/16/2019 213,133.45 E7 00000077 BOUGAMBILIAS CONSTRUCTION LLC. Perez Elementary- Consolidatio 08/16/2019 23,965.00 E7 00000078 CENTENNIAL CONTRACTORS ENTERPR Del Castillo Elementary- Roof 08/16/2019 153,230.85 E7 00000079 E3 ENTEGRAL SOLUTIONS INC. -PACE ECHS (003) 08/16/2019 1,794,657.91 E7 00000080 GONZALEZ ENGINEERING & SURVEYI Board Approved Contract for Pr 08/16/2019 2,002.17 E7 00000081 MONTENEGRO'S PAVING & HAULING Item #7-6" Cement 3500 PSI wit 08/16/2019 56,807.55 E7 00000082 NM CONTRACTING LLC. Cummings CTE CV1 Canopy Improv 08/16/2019 98,475.71 E7 00000083 PBK ARCHITECTS Southmost Elementary - Roof Re 08/16/2019 1,375.00 E7 00000084 SCHNEIDER ELECTRIC Design Build HVAC Phase II 08/16/2019 1,502,593.80 E7 00000085 GONZALEZ GLASS Perez Elementary-Consolidation 08/16/2019 79,233.02 E7 00000086 MOORE SUPPLY COMPANY Canales Elementary - Consolida 08/16/2019 7,677.87 E7 00000087 CPM DESIGN LLC. -

March/April, 1990

t i MM—MM rl '"-^^^~zzz^~-^^ Coca-Cola signed as League's first corporate sponsor BY PETER CONTRERAS $461,450 last year for Public Information 361 academic scholar Director ships to students to The University attend Texas univer Intcrscholastic sities and colleges. League and Coca- "Other funds Cola have entered derived from this into ah agreement in agreement will go principle that makes toward improving the soft drink com theovcrall program," pany the first corpo Marshall continued. rate sponsor of UIL "Some of the funds activities. will be designated to Dr. Bailey upgraderegionaland Marshall, UIL director, and Ted Faubel of state meets and tournaments and to de Austin, a sales development account velop a greater range of instructional manager for Coca-Cola, made the an multi-media materials for teachers and nouncement during the boys' state bas students." ketball tournament in Austin in early Funds will also be used to increase March. the interest in and support of UIL pro 'The focus of all UIL activities is the grams at the local and state levels, Marshall student," Marshall said. "Academic, ath concluded. letic and fine arts contests are created, In return, Coca-Cola gets advertising "organized and administered with the in UIL publications and special recogni dominant intention of enriching the stu tion at UIL state events, but its name will dent's total educational experience. The not be included in the title of state cham UIL has entered the realm of corporate pionships events. sponsorship with the same philosophy." "If we were looking at it strictly as an Under the agreement, the UIL will advertising vehicle, we could have gotten receive 5125,000 in cash, $100,000 for its a lot more bang for our dollar by going scholarship foundation and more than with commercials," said Faubel. -

Institutes for Texas Teachers

Humanities Texas, the state af!liate of the National Endowment for the Humanities, conducts and supports public programs in history, literature, philosophy, and other humanities disciplines. These programs strengthen Texas communities and ultimately help sustain representative democracy by cultivating informed, educated citizens. www.humanitiestexas.org As the largest school at The University of Texas at Austin, the College of Liberal Arts forms the core of the university experience: a classic liberal arts education at a world-class research university. The college provides intellectual challenges, exposure to diversity, and learning opportunities that cross cultural boundaries and promote individual growth. Top-ranked programs set the standard for undergraduate excellence. www.utexas.edu/cola The University of Texas at San Antonio is dedicated to the advancement of knowledge through research and discovery, teaching and learning, community engagement and public service. As an institution of access and excellence, UTSA embraces multicultural traditions, serving as a center for intellectual and creative resources as well as a catalyst for socioeconomic development for Texas, the nation, and the world. www.utsa.edu The mission of the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum is to preserve and protect the historical materials in the collections institutes for texas teachers of the Johnson Library and make them readily accessible, to increase public awareness of the American experience through relevant exhibitions and educational programs, and to advance the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum’s standing as a center for intellectual activity and community leadership while meeting the challenges of a changing world. www.lbjlib.utexas.edu A We the People initiative of the National Endowment for the Humanities, with support from Houston Endowment, a philanthropy endowed by Mr. -

2015-16 TGCA Volleyball Academic All-State Selections

2015-16 TGCA Volleyball Academic All-State Selections Athlete First Athlete Last High School Coach First Coach Last Conf. 1A Sara English ASPERMONT HIGH SCHOOL Rebekah Bland 1A Jacy Sparks ASPERMONT HIGH SCHOOL Rebekah Bland 1A Macy Higgins BLUM HIGH SCHOOL Lauren McPherson 1A Rhealee Spies BURTON HIGH SCHOOL Katie Cloud 1A Cali Porter FORT DAVIS HIGH SCHOOL Gary Lamar 1A Kristina Mayo GARY HIGH SCHOOL Tamika Hubbard 1A Sydney Ritter GARY HIGH SCHOOL Tamika Hubbard 1A Cheyenne Camp KNOX CITY HIGH SCHOOL Brenna Hoegger 1A Cortlyn Barnes MEDINA HIGH SCHOOL Lovey Sockol 1A Hannah Garrison MEDINA HIGH SCHOOL Lovey Sockol 1A Chyna Phillips MEDINA HIGH SCHOOL Lovey Sockol 1A Whitley Whitewood MEDINA HIGH SCHOOL Lovey Sockol 1A Aurora Denise Araujo MUNDAY SECONDARY SCHOOL Jessica Toliver 1A Skylar Gomez MUNDAY SECONDARY SCHOOL Jessica Toliver 1A Kimberly Shahan MUNDAY SECONDARY SCHOOL Jessica Toliver 1A Ana Vega MUNDAY SECONDARY SCHOOL Jessica Toliver 1A Kiera Cosby NORTH ZULCH HIGH SCHOOL Gregory Horn 1A Jasmine D Willis OAKWOOD HIGH SCHOOL Mike Hill 1A Kendall Deaton PADUCAH HIGH SCHOOL Sandra Tribble 1A Leslie Mayo PADUCAH HIGH SCHOOL Sandra Tribble 1A Madison Heyman ROUND TOP‐CARMINE HIGH SCHOOL RaChelle Etzel 1A Adyson Lange ROUND TOP‐CARMINE HIGH SCHOOL RaChelle Etzel 1A Emma Leppard ROUND TOP‐CARMINE HIGH SCHOOL RaChelle Etzel 1A Cheyenne Janssen RUNGE HIGH SCHOOL Melissa Lopez 1A Brittany Rauch STERLING CITY HIGH SCHOOL Amelia Reeves 1A Verenise Aguirre TIOGA SCHOOL Mindy Patton 1A Samantha Holcomb TIOGA SCHOOL Mindy Patton 1A Heather -

The Collegian (2008-08-25)

University of Texas Rio Grande Valley ScholarWorks @ UTRGV The Collegian Special Collections and Archives 8-25-2008 The Collegian (2008-08-25) Isis Lopez The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.utrgv.edu/collegian Recommended Citation The Collegian (BLIBR-0075). UTRGV Digital Library, The University of Texas – Rio Grande Valley This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections and Archives at ScholarWorks @ UTRGV. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Collegian by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UTRGV. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. THE STUDENT VOICE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT BROWNSVILLE AND TEXAS SOUTHMOST COLLEGE THE Volume 61 Monday OLLEGIANwww.collegian.utb.edu CIssue 2 August 25, 2008 TSC tax rate hearing Thursday Enrollment By Julianna Sosa operating budget of the district --Property acquisition, raise the same amount of dollars up slightly Staff Writer is funded by tax revenues, which $1,250,000 as the 2007 rate; and the rollback provide funding for scholarships, --Insurance, $1,177,683 rate, which is 16.51 cents and By Julianna Sosa The first of two public hearings capital improvements, deferred --Institutional Advancement would generate 8 percent more in Staff Writer on the proposed 2008 Texas maintenance, insurance and (partnership budget/grant writers), revenue than the 2007 rate. Southmost College District tax administration. $530,169 Sanchez gave two examples A total of 11,581 students were rate is set for 5 p.m. Thursday in Melba Sanchez, assistant vice --Library (partnership budget), showing the effect of the tax rates registered for classes at UTB/TSC the Gorgas Hall boardroom. -

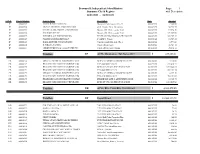

BR: Summary Check Register with Desc 06042015

Brownsville Independent School District Page: 1 Summary Check Register with Description 06/01/2021 - 06/30/2021 FUND Check Number Vendor Name Description Date Amount E7 00000323 AMTECH SOLUTIONS INC. Margaret Clark Aquatic Ctr.- R 06/04/2021 2,800.00 E7 00000324 ARAIZA GENERAL CONSTRUCTION #101 Canales Elem. Demolition 06/04/2021 34,966.33 E7 00000325 CENTRAL AIR AND HEATING SERVIC Margaret M. Clark Aquatic Cent 06/04/2021 15,874.50 E7 00000326 RIO ROOFING INC. Margaret M. Clark Aquatic Cent 06/04/2021 121,505.00 E7 00000327 VICTORIA AIR CONDITIONING RIVERA ECHS-HVAC & LED LIGHTNI 06/04/2021 181,787.19 E7 00000328 CHANIN ENGINEERING LLC. Faulk M.S. Canopy 06/09/2021 14,927.10 E7 00000329 RABA KISTNER CONSULTANTS Constructional Materials Obser 06/28/2021 1,574.66 E7 00000330 R. PIZANA PAVING Canales Elementary- 06/29/2021 36,724.40 E7 00000331 GREEN-RUBIANO & ASSOCIATES INC Canales Elementary Canopy 06/30/2021 25,646.43 Total for: E7 ACH - Maintenance Tax Notes 2017 $ 435,805.61 EB 00000188 MIRACLE MEDICAL EQUIPMENT AND MIRACLE MEDICAL DIABETIC SUPPL 06/01/2021 3,110.00 EB 00000189 HEALTH CARE SERVICE CORPORATIO TXAA4010005 5/28/21 06/02/2021 859,410.79 EB 00000190 HEALTH CARE SERVICE CORPORATIO BCBS STOP LOSS FEES FOR SPECIF 06/11/2021 1,095,040.83 EB 00000191 HEALTH CARE SERVICE CORPORATIO TXAA4010005 6/11/21 06/15/2021 661,101.74 EB 00000192 MIRACLE MEDICAL EQUIPMENT AND MIRACLE MEDICAL DIABETIC SUPPL 06/15/2021 4,227.50 EB 00000193 HEALTH CARE SERVICE CORPORATIO TXAA4010005 6/18/21 06/23/2021 763,151.67 EB 00000194 DEARBORN LIFE INSURANCE -

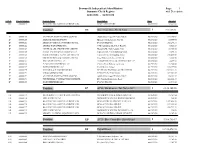

BR: Summary Check Register with Desc 06042015

Brownsville Independent School District Page: 1 Summary Check Register with Description 06/01/2020 - 06/30/2020 FUND Check Number Vendor Name Description Date Amount BC 00000075 HEALTH CARE SERVICE CORPORATIO STOP LOSS CREDIT 06/22/2020 772,668.61 Total for: BC Blue Cross-Blue Shield Fund $ 772,668.61 E7 00000179 AMERICAN CONTRACTING USA INC. (#005) Cummings CTE-Unit D & V 06/23/2020 127,746.02 E7 00000180 AMTECH SOLUTIONS INC. Margaret Clark Aquatic Ctr.- R 06/23/2020 15,000.00 E7 00000181 ARGIO ROOFING & CONSTRUCTION L FV1718-XXX-001 06/23/2020 382,278.31 E7 00000182 ARMKO INDUSTRIES INC. CTE Cummings-BLA H.S. Roof Re- 06/23/2020 5,523.87 E7 00000183 CENTRAL AIR AND HEATING SERVIC Margaret M. Clark Aquatic Cent 06/23/2020 11,400.00 E7 00000184 ETHOS-HOTISTIQUE HOLDINGS LLC. Hanna ECHS-CATE Building Const 06/23/2020 1,698.75 E7 00000185 GOMEZ-MENDEZ-SAENZ ARCHITECTS Canales Elem.-Re-Roofing Archi 06/23/2020 131,400.00 E7 00000186 GREEN-RUBIANO & ASSOCIATES INC Food Nutrition Services(FNS)-W 06/23/2020 1,000.00 E7 00000187 NM CONTRACTING LLC. CUMMINGS CTE-CV4 TECHNOLOGY UP 06/23/2020 4,639.68 E7 00000188 PLAGAR ENGINEERING LLC. Canales Elem Parking Lot Impro 06/23/2020 15,900.00 E7 00000189 RG ENTERPRISES LLC. Faulk Middle School 06/23/2020 124,279.00 E7 00000190 VICTORIA AIR CONDITIONING RIVERA ECHS-HVAC & LED LIGHTIN 06/23/2020 1,907,611.28 E7 00000191 ZIWA CORPORATION EP20029 ME-1718-913-001 06/23/2020 109,501.69 E7 00000192 AMERICAN CONTRACTING USA INC. -

COVID-19 Food and Social Services Resources

Version 2 3-27-2020 COVID-19 Food and Social Services FOOD ASSISTANCE 1. RGV Food Bank -956-682-8101 Call this number for both Cameron and Hidalgo county participants and select option 2 for food assistance to get a pantry referral closest to the participants address. RGV Food Bank for Seniors Only: Thursday 9:30 am to 11:30 am. (First come first serve) RGV Food Bank Emergency Food: Tuesdays and Thursdays 8 am to 5 pm. RGV Food Bank also has a senior commodity program for low-income individuals over age 60. At this time they stopped food distribution in March due to Covid-19 precautions and are going to let me know if they will have food distribution in April. 2. The Salvation Army helps cure hunger daily by providing nutritious meals to anyone in need. This includes homeless people of all ages, as well as individuals and families who may be down on their luck and in need of some extra assistance. In addition to addressing the immediate symptoms of food insecurity, our programs are designed to help identify and treat its root cause. Over time, this holistic approach to the physical, mental and spiritual needs of each person helps moves many from ‘hungry’ to ‘fully healed.’ Salvation Army of McAllen 956-682-1468 1600 N. 23rd Street McAllen, TX 78501 Salvation Army of Harlingen 956-423-2454 119 E. Monroe Avenue Harlingen, TX 78550 3 Amigos Del Valle, Inc. Hidalgo, Willacy, Cameron Visit online at www.advrgv.org or at (956) 213-9400 Centers are open at this time and will be serving food on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. -

Uil Region 28 Region Executive Committee Email Meeting, Tuesday, October 30, 2018

UIL REGION 28 REGION EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE EMAIL MEETING, TUESDAY, OCTOBER 30, 2018 1. Welcome, and Recognition of Region and Area Marching Contest results and Bands Certified to State I would like to welcome all of our committee members, Mr. Ismael Garcia, Rio Hondo ISD superintendent and committee chair, Dr. Arturo Cavazos, Harlingen CISD superintendent, Dr. Gonzalo Salazar, Los Fresnos CISD superintendent, Dr. Daniel Trevino, Mercedes ISD superintendent, Dr. Priscilla Canales, Weslaco ISD superintendent, Dr. Lisa Garcia, Point Isabel ISD superintendent, and Mr. Eduardo Infante, Lyford CISD superintendent, as well as any proxy s/he may have designated. Thank you for serving on this committee. Pigskin Jubilee 2018 was held in two locations on Saturday, October 20, 2018. The 6A Bands performed at the Bobby Lackey Stadium in the Weslaco ISD. Event judges were: Dennis Hopkins, Pittsburg, TX; Tammy Fedynich, Lubbock, TX, and Trevor Braselton, Dickinson High School, Dickinson, Texas. All nine bands participating presented superior performances (in spite of occasional mist and rain and an occasional downpour) and all nine bands received unanimous division I ratings (advancing them all from Region to Area G 6A Marching Contest). Performance order of bands was as follows: Brownsville Rivera Early College High School, Harlingen High School, Donna North High School, Weslaco High School, San Benito High School, Harlingen South High School, Weslaco East High School, Los Fresnos High School and Brownsville Homer Hanna High School. The 2A, 3A, 4A and 5A bands performed at the Mercedes ISD Tiger Stadium, also enduring challenging mist, rain and the occasional downpour. Judges were Mike Olson, New Braunfels, TX; Daniel Solis, San Antonio, TX; and Armando Robledo, Cy-Ridge HS, Houston. -

May, 1990 Conference AA News Writing 1

: ^^ 9lfftU*f «..—^^^- ^J^**^ ^7"^— ^^ ^*— j^^m ^T—V^^^. m&~rr. TV.. •• *H| •.-•_; ^_,_JJM*****IIII 11 "" ^*"i^0*" ""**%;:::.':::::::::Vf M"MI" ' ,l" • • * • • "• i l : v ,j •"-'' ""•- • ^S^v:-:v^,.'r.|r '* 'lY ' - ^^ A GRAND idea Denius-UIL Excellence Award to honor contributions made by contest sponsors The UIL is completing plans for the the 10 chosen to receive the awards will creation of a program to make cash receive a $1000 cash award and an awards to 10 outstanding sponsors of appropriate symbolic momento. school activities. The program, called Among the criteria to be considered the Denius-UIL Sponsor Excellence in the selection process are: Award, seeks to "identify and recognize • accomplishments of students as a each year 10 outstanding sponsors who result of the sponsor's leadership over a assist students in developing and 5-year period; refining their extracurricular talents to • indications that the sponsor is the highest degree possible," said Dr. receiving maximum results from Bill Stamps, assistant to the UIL existing resources; director. "We have the large elements • and recommendation of the for the scholarship set, although we sponsor by the principal as an effective have not finalized all aspects of the teacher in non-UIL classroom activities. program." Also, nominees will be required to Dr. Bailey Marshall, UIL director, submit a philosophical statement said the League has been concerned that regarding the role of competitive contest sponsors do not receive the activities in the secondary curriculum. recognition that they deserve. "We The selection committee will recognize that the quality of the benefits attempt to recognize sponsors from each of educational competition for students of the three categories of UIL activities, is directly attributable to theknowledge, Stamps said. -

Decade 1930 to 1939

Decade 1930 to 1939 Developments 1930 The U.S. Census has Harlingen population at 12,124. At this point Harlingen begins to surpass its San Benito neighbor in population and economic indicators. Whereas San Benito had a 1920 population of 5,070 in 1910, it has only doubled to 10, 753 by 1930. Harlingen meanwhile has leaped almost seven times from its 1920 total of 1,784. Adams Garden tract of 12,124 acres to the west of Stuart Place commences development with brush clearing. Its initial citrus plantings and land sales are by Charles F. C. Ladd and are subsequently taken over by Sid Berly. 1/14/30 Missouri Pacific and the Southern Pacific report that over 1000 homeseekers are in the Valley this week. 6/30 Key statistics put telephone connections at 1,550, light connections at 2,330, water connections at 1,615. Postal receipts total $51,410. Assessed valuation is $9,436,051. 7/23 Harlingen leads all Valley cities in general construction with a $1,417,000 total. 1932 This is a difficult time economically for the city as well as the country. To promote growth here the Harlingen Community League is formed "For the Advancement and Continued Progress of Harlingen and the Valley." The list of individuals on its letterhead speak for their prominence. W.L. Trammel is president; Charles F.C. Ladd, vp; Joe Penry, treasurer; John T. Floore, secretary-manager; Ray V. Gillispie, traffic manager; Bishop Clements, publicity director; and on the directorate are O.P. Storm, capitalist; J.J. Burk, Reese-Wil-Mond Hotel; V.V.