English Blasphemy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The E Book 2021–2022 the E Book

THE E BOOK 2021–2022 THE E BOOK This book is a guide that sets the standard for what is expected of you as an Exonian. You will find in these pages information about Academy life, rules and policies. Please take the time to read this handbook carefully. You will find yourself referring to it when you have questions about issues ranging from the out-of-town procedure to the community conduct system to laundry services. The rules and policies of Phillips Exeter Academy are set by the Trustees, faculty and administration, and may be revised during the school year. If changes occur during the school year, the Academy will notify students and their families. All students are expected to follow the most recent rules and policies. Procedures outlined in this book apply under normal circumstances. On occasion, however, a situation may require an immediate, nonstandard response. In such circumstances, the Academy reserves the right to take actions deemed to be in the best interest of the Academy, its employees and its students. This document as written does not limit the authority of the Academy to alter its rules and procedures to accommodate any unusual or changed circumstances. If you have any questions about the contents of this book or anything else about life at Phillips Exeter Academy, please feel free to ask. Your teachers, your dorm proctors, Student Listeners, and members of the Dean of Students Office all are here to help you. Phillips Exeter Academy 20 Main Street, Exeter, New Hampshire Tel 603-772-4311 • www.exeter.edu 2021 by the Trustees of Phillips Exeter Academy HISTORY OF THE ACADEMY Phillips Exeter Academy was founded in 1781 A gift from industrialist and philanthropist by Dr. -

BLASPHEMY LAWS in the 21ST CENTURY: a VIOLATION of HUMAN RIGHTS in PAKISTAN Fanny Mazna Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected]

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School 2017 BLASPHEMY LAWS IN THE 21ST CENTURY: A VIOLATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN PAKISTAN Fanny Mazna Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp Recommended Citation Mazna, Fanny. "BLASPHEMY LAWS IN THE 21ST CENTURY: A VIOLATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN PAKISTAN." (Jan 2017). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Papers by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BLASPHEMY LAWS IN THE 21ST CENTURY A VIOLATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN PAKISTAN by Fanny Mazna B.A., Kinnaird College for Women, 2014 A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Science Department of Mass Communication and Media Arts in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale May 2017 RESEARCH PAPER APPROVAL BLASPHEMY LAWS IN THE 21ST CENTURY A VIOLATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN PAKISTAN By Fanny Mazna A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in the field of Mass Communication and Media Arts Approved by: William Babcock, Co-Chair William Freivogel, Co-Chair Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale April, 6th 2017 AN ABSTRACT OF THE RESEARCH PAPER OF FANNY MAZNA, for the Master of Science degree in MASS COMMUNICATION AND MEDIA ARTS presented on APRIL, 6th 2017, at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. TITLE: BLASPHEMY LAWS IN THE 21ST CENTURY- A VIOLATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN PAKISTAN MAJOR PROFESSOR: Dr. -

Statement by Dr. Richard Benkin

Dr. Richard L. Benkin ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Email: [email protected] http://www.InterfaithStrength.com Also Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn Bangladesh: “A rose by any other name is still blasphemy.” Written statement to US Commission on Religious Freedom Virtual Hearing on Blasphemy Laws and the Violation of International Religious Freedom Wednesday, December 9, 2020 Dr. Richard L. Benkin Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states: “Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.” While few people champion an unrestricted right to free of expression, fewer still stand behind the use of state power to protect a citizen’s right from being offended by another’s words. In the United States, for instance, a country regarded by many correctly or not as a “Christian” nation, people freely produce products insulting to many Christians, all protected, not criminalized by the government. A notorious example was a painting of the Virgin Mary with elephant dung in a 1999 Brooklyn Museum exhibit. Attempts to ban it or sanction the museum failed, and a man who later defaced the work to redress what he considered an anti-Christian slur was convicted of criminal mischief for it. Laws that criminalize free expression as blasphemy are incompatible with free societies, and nations that only pose as such often continue persecution for blasphemy in disguise. In Bangladesh, the government hides behind high sounding words in a toothless constitution while sanctioning blasphemy in other guises. -

Revue Française De Civilisation Britannique, XVIII-1 | 2013 Orthodoxy, Heresy and Treason in Elizabethan England 2

Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique French Journal of British Studies XVIII-1 | 2013 Orthodoxie et hérésie dans les îles Britanniques Orthodoxy, Heresy and Treason in Elizabethan England Orthodoxie, hérésie et trahison dans l’Angleterre élisabéthaine Claire Cross Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/rfcb/3561 DOI: 10.4000/rfcb.3561 ISSN: 2429-4373 Publisher CRECIB - Centre de recherche et d'études en civilisation britannique Printed version Date of publication: 1 March 2013 ISBN: 2-911580-37-0 ISSN: 0248-9015 Electronic reference Claire Cross, « Orthodoxy, Heresy and Treason in Elizabethan England », Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique [Online], XVIII-1 | 2013, Online since 01 March 2013, connection on 20 March 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/rfcb/3561 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/rfcb.3561 This text was automatically generated on 20 March 2020. Revue française de civilisation britannique est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Orthodoxy, Heresy and Treason in Elizabethan England 1 Orthodoxy, Heresy and Treason in Elizabethan England Orthodoxie, hérésie et trahison dans l’Angleterre élisabéthaine Claire Cross 1 Despite the severe penalties laid down in the Acts of Supremacy and Uniformity of 1559, the Elizabethan Government initially displayed great unwillingness to proceed against Catholics for their religious beliefs, but changed its stance on the promulgation of the papal bull of 1570 which excommunicated the queen and released her subjects from their allegiance. At the beginning of the reign, Protestant and Catholic controversialists in their publications concentrated upon whether the English Church could be considered to be a true Church; after the State began prosecuting seminary priests and their lay protectors for treason, the debate moved on to whether Catholics were being put to death exclusively for a political crime or sacrificing their lives solely for their faith. -

Anglo-Jewry's Experience of Secondary Education

Anglo-Jewry’s Experience of Secondary Education from the 1830s until 1920 Emma Tanya Harris A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements For award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Hebrew and Jewish Studies University College London London 2007 1 UMI Number: U592088 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U592088 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract of Thesis This thesis examines the birth of secondary education for Jews in England, focusing on the middle classes as defined in the text. This study explores various types of secondary education that are categorised under one of two generic terms - Jewish secondary education or secondary education for Jews. The former describes institutions, offered by individual Jews, which provided a blend of religious and/or secular education. The latter focuses on non-Jewish schools which accepted Jews (and some which did not but were, nevertheless, attended by Jews). Whilst this work emphasises London and its environs, other areas of Jewish residence, both major and minor, are also investigated. -

A Preface to Swift's Test Act Tracts

Ian Higgins The Australian National University, Canberra A Preface to Swift’s Test Act Tracts Abstract. There are seven securely canonical polemical works by Jonathan Swift that are primarily concerned with opposing Whig attempts to repeal the Sacramental Test in favour of Protestant Dissenters in Ireland. They are occasional prose works, polemical interventions in topical controversies over the repeal attempts of 1707–9 and 1732–33. In his Test Act tracts, and in other polemical and satirical writings, Swift responds to an array of Dissenting arguments arraigned against the Sacramental Test. One of these Dissenting anti-Test argu- ments was that temporal rewards for religious conformity and penalties for Nonconformity encouraged religious hypocrisy. Swift’s response to this argument has become notorious. This essay will offer a short view of Swift on the Sacramental Test and hypocrisy. It will notice the kinds of general argument Swift drew upon in defence of conformity and for imposing civil disabilities on Dissenters. I The Sacramental Test, in Swift’s words, “obliges all Men, who enter into Office under the Crown, to receive the Sacrament according to the Rites of the Church of Ireland.”1 The Test Act had been imposed in England in 1673 after the forced withdrawal of Charles II’s Second Declaration of Indulgence in 1672. It required “that all and every person or persons … that shall bear any office or offices, civil or military” must take “the Sacrament of the Lords Supper according to the usage of the Church of England.” The Test Act of 1678 further required all Members of Parliament to make a declaration against the Roman Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation.2 After the passing of the Toleration Act in 1689, the Test Acts were the principal bulwark of the Anglican confessional state or at least of the Anglican monopoly of public office. -

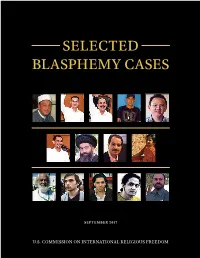

Selected Blasphemy Cases

SELECTED BLASPHEMY CASES SEPTEMBER 2017 U.S. COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM Mohamed Basuki “Ahok” Abdullah al-Nasr Andry Cahya Ahmed Musadeq Sebastian Joe Tjahaja Purnama EGYPT INDONESIA INDONESIA INDONESIA INDONESIA Ayatollah Mohammad Mahful Muis Kazemeini Mohammad Tumanurung Boroujerdi Ali Taheri Aasia Bibi INDONESIA IRAN IRAN PAKISTAN Ruslan Sokolovsky Abdul Shakoor RUSSIAN Raif Badawi Ashraf Fayadh Shankar Ponnam PAKISTAN FEDERATION SAUDI ARABIA SAUDI ARABIA SAUDI ARABIA UNITED STATES COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM SELECTED BLASPHEMY CASES SEPTEMBER 2017 WWW.USCIRF.GOV COMMISSIONERS Daniel Mark, Chairman Sandra Jolley, Vice Chair Kristina Arriaga de Bucholz, Vice Chair Tenzin Dorjee Clifford D. May Thomas J. Reese, S.J. John Ruskay Jackie Wolcott Erin D. Singshinsuk Executive Director PROFESSIONAL STAFF Dwight Bashir, Director of Research and Policy Elizabeth K. Cassidy, Director of International Law and Policy Judith E. Golub, Director of Congressional Affairs & Policy and Planning John D. Lawrence, Director of Communications Elise Goss-Alexander, Researcher Andrew Kornbluth, Policy Analyst Tiffany Lynch, Senior Policy Analyst Tina L. Mufford, Senior Policy Analyst Jomana Qaddour, Policy Analyst Karen Banno, Office Manager Roy Haskins, Manager of Finance and Administration Travis Horne, Communications Specialist SELECTED BLASPHEMY CASES Many countries today have blasphemy laws. Blasphemy is defined as “the act of insulting or showing contempt or lack of reverence for God.” Across the globe, billions of people view blasphemy as deeply offensive to their beliefs. Respecting Rights? Measuring the World’s • Violate international human rights standards; Blasphemy Laws, a U.S. Commission on Inter- • Often are vaguely worded, and few specify national Religious Freedom (USCIRF) report, or limit the forum in which blasphemy can documents the 71 countries – ranging from occur for purposes of punishment; Canada to Pakistan – that have blasphemy • Are inconsistent with the approach laws (as of June 2016). -

Blasphemy Law and Public Neutrality in Indonesia

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vol 8 No 2 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy March 2017 Research Article © 2017 Victor Imanuel W. Nalle. This is an open access article licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/). Blasphemy Law and Public Neutrality in Indonesia Victor Imanuel W. Nalle Faculty of Law, Darma Cendika Catholic University, Indonesia Doi:10.5901/mjss.2017.v8n2p57 Abstract Indonesia has the potential for social conflict and violence due to blasphemy. Currently, Indonesia has a blasphemy law that has been in effect since 1965. The blasphemy law formed on political factors and tend to ignore the public neutrality. Recently due to a case of blasphemy by the Governor of Jakarta, relevance of blasphemy law be discussed again. This paper analyzes the weakness of the blasphemy laws that regulated in Law No. 1/1965 and interpretation of the Constitutional Court on the Law No. 1/1965. The analysis in this paper, by statute approach, conceptual approach, and case approach, shows the weakness of Law No. 1/1965 in putting itself as an entity that is neutral in matters of religion. This weakness caused Law No. 1/1965 set the Government as the interpreter of the religion scriptures that potentially made the state can not neutral. Therefore, the criminalization of blasphemy should be based on criteria without involving the state as an interpreter of the theological doctrine. Keywords: constitutional right, blasphemy, religious interpretation, criminalization, public neutrality 1. Introduction Indonesia is a country with a high level of trust toward religion. -

FAITH, INTOLERANCE, VIOLENCE and BIGOTRY Legal and Constitutional Issues of Freedom of Religion in Indonesia1 Adam J

DOI: 10.15642/JIIS.2016.10.2.181-212 Freedom of Religion in Indonesia FAITH, INTOLERANCE, VIOLENCE AND BIGOTRY Legal and Constitutional Issues of Freedom of Religion in Indonesia1 Adam J. Fenton London School of Public Relations, Jakarta - Indonesia | [email protected] Abstract: Religious intolerance and bigotry indeed is a contributing factor in social and political conflict including manifestations of terrorist violence. While freedom of religion is enshrined in ,ndonesia’s Constitution, social practices and governmental regulations fall short of constitutional and international law guarantees, allowing institutionalised bias in the treatment of religious minorities. Such bias inhiEits ,ndonesia’s transition to a fully-functioning pluralistic democracy and sacrifices democratic ideals of personal liberty and freedom of expression for the stated goals of religious and social harmony. The Ahok case precisely confirms that. The paper examines the constitutional bases of freedom of religion, ,ndonesia’s Blasphemy Law and takes account of the history and tenets of Pancasila which dictate a belief in God as the first principle of state ideology. The paper argues that the ,ndonesian state’s failure to recognise the legitimacy of alternate theological positions is a major obstacle to Indonesia recognising the ultimate ideal, enshrined in the national motto, of unity in diversity. Keywords: freedom of religion, violence, intolerance, constitution. Introduction This field of inquiry is where philosophy, religion, politics, terrorism–even scientific method–all converge in the arena of current 1 Based on a paper presented at the International Indonesia Forum IX, 23-24 August 2016 Atma Jaya Catholic University, Jakarta. JOURNAL OF INDONESIAN ISLAM Volume 10, Number 02, December 2016 181 Adam J. -

No Longer an Alien, the English Jew: the Nineteenth-Century Jewish

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1997 No Longer an Alien, the English Jew: The Nineteenth-Century Jewish Reader and Literary Representations of the Jew in the Works of Benjamin Disraeli, Matthew Arnold, and George Eliot Mary A. Linderman Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Linderman, Mary A., "No Longer an Alien, the English Jew: The Nineteenth-Century Jewish Reader and Literary Representations of the Jew in the Works of Benjamin Disraeli, Matthew Arnold, and George Eliot" (1997). Dissertations. 3684. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/3684 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1997 Mary A. Linderman LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO "NO LONGER AN ALIEN, THE ENGLISH JEW": THE NINETEENTH-CENTURY JEWISH READER AND LITERARY REPRESENTATIONS OF THE JEW IN THE WORKS OF BENJAMIN DISRAELI, MATTHEW ARNOLD, AND GEORGE ELIOT VOLUME I (CHAPTERS I-VI) A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH BY MARY A. LINDERMAN CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JANUARY 1997 Copyright by Mary A. Linderman, 1997 All rights reserved. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to acknowledge the invaluable services of Dr. Micael Clarke as my dissertation director, and Dr. -

Blasphemy in a Secular State: Some Reflections

BLASPHEMY IN A SECULAR STATE: SOME REFLECTIONS Belachew Mekuria Fikre ♣ Abstract Anti-blasphemy laws have endured criticism in light of the modern, secular and democratic state system of our time. For example, Ethiopia’s criminal law provisions on blasphemous utterances, as well as on outrage to religious peace and feeling, have been maintained unaltered since they were enacted in 1957. However, the shift observed within the international human rights discourse tends to consider anti-blasphemy laws as going against freedom of expression. The recent Human Rights Committee General Comment No. 34 calls for a restrictive application of these laws for the full realisation of many of the rights within the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Secularism and human rights perspectives envisage legal protection to the believer and not the belief. Lessons can be drawn from the legal framework of defamation which considers injuries to the person rather than to institutions or to the impersonal sacred truth. It is argued that secular states can ‘promote reverence at the public level for private feelings’ through well-recognised laws of defamation and prohibition of hate speech rather than laws of blasphemy. This relocates the role of the state to its proper perspective in the context of its role in promoting interfaith dialogue, harmony and tolerance. Key words Blasphemy, Secular, Human Rights, Freedom of Expression, Defamation of Religion DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/mlr.v7i1.2 _____________ Introduction The secular as ‘an epistemic category’, and secularism as a value statement, have been around since the 1640s Peace of Westphalia, otherwise called the ‘peace of exhaustion’, and they remain one of the contested issues in today’s world political discourse. -

Measuring the World's Blasphemy Laws

RESPECTING RIGHTS? Measuring the World’s Blasphemy Laws U.S. COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM A gavel is seen in a hearing room in Panama City April 7, 2016. REUTERS/Carlos Jasso UNITED STATES COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM RESPECTING RIGHTS? Measuring the World’s Blasphemy Laws By Joelle Fiss and Jocelyn Getgen Kestenbaum JULY 2017 WWW.USCIRF.GOV COMMISSIONERS Daniel Mark, Chairman Sandra Jolley, Vice Chair Kristina Arriaga de Bucholz, Vice Chair Tenzin Dorjee Clifford D. May Thomas J. Reese, S.J. John Ruskay Jackie Wolcott Erin D. Singshinsuk Executive Director PROFESSIONAL STAFF Dwight Bashir, Director of Research and Policy Elizabeth K. Cassidy, Director of International Law and Policy Judith E. Golub, Director of Congressional Affairs & Policy and Planning John D. Lawrence, Director of Communications Sahar Chaudhry, Senior Policy Analyst Elise Goss-Alexander, Researcher Andrew Kornbluth, Policy Analyst Tiffany Lynch, Senior Policy Analyst Tina L. Mufford, Senior Policy Analyst Jomana Qaddour, Policy Analyst Karen Banno, Office Manager Roy Haskins, Manager of Finance and Administration Travis Horne, Communications Specialist This report, containing data collected, coded, and analyzed as of June 2016, was overseen by Elizabeth K. Cassidy, J.D., LL.M, Director of International Law and Policy at the U.S. Commis- sion on International Religious Freedom. At USCIRF, Elizabeth is a subject matter expert on international and comparative law issues related to religious freedom as well as U.S. refugee and asylum policy.