Blasphemy in a Secular State: Some Reflections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNITED ARAB EMIRATES UNITED ARAB EMIRATES RELIGIONS 1.1% 1.9% Agnostics Buddhists 1.3% Other 11.0% Christians 6.2% Hindus

Religious Freedom in the World Report 2021 UNITED ARAB EMIRATES UNITED ARAB EMIRATES RELIGIONS 1.1% 1.9% Agnostics Buddhists 1.3% Other 11.0% Christians 6.2% Hindus Population Area 9,813,170 83,600 Km2 78.5% GDP per capita GINI INDEX* Muslims 67,293 US$ 32.5 *Economic Inequality tion of committing adultery.”2 Article 1 of the penal code LEGAL FRAMEWORK ON FREEDOM OF RELIGION provides that Islamic law applies in hudud cases, including AND ACTUAL APPLICATION the payment of blood money in cases of murder. Article 66 states that the “original punishments” under the law apply to hudud crimes, including the death penalty. No one, The United Arab Emirates (UAE) is a federation of seven however, has been prosecuted or punished by a court for emirates situated in the Persian Gulf. Dubai is politically such an offence. and economically the most important of them. The law criminalises blasphemy and imposes fines and According to the constitution of 1971,1 Islam is the official imprisonment in these cases. Insulting other religions is religion of the federation. Article 7 reads: “Islam is the of- also banned. Non-citizens face deportation in case of ficial religion of the UAE. Islamic Shari‘a is a main source blasphemy. of legislation in the UAE.” Article 25 excludes discrimina- tion based on religion. It states: “All persons are equal in While Muslims may proselytise, penalties are in place for law. There shall be no distinction among the citizens of the non-Muslims doing the same among Muslims. If caught, UAE on the basis of race, nationality, faith or social status.” non-citizens may have their residency revoked and face Article 32 states: “Freedom to exercise religious worship deportation. -

BLASPHEMY LAWS in the 21ST CENTURY: a VIOLATION of HUMAN RIGHTS in PAKISTAN Fanny Mazna Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected]

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School 2017 BLASPHEMY LAWS IN THE 21ST CENTURY: A VIOLATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN PAKISTAN Fanny Mazna Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp Recommended Citation Mazna, Fanny. "BLASPHEMY LAWS IN THE 21ST CENTURY: A VIOLATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN PAKISTAN." (Jan 2017). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Papers by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BLASPHEMY LAWS IN THE 21ST CENTURY A VIOLATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN PAKISTAN by Fanny Mazna B.A., Kinnaird College for Women, 2014 A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Science Department of Mass Communication and Media Arts in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale May 2017 RESEARCH PAPER APPROVAL BLASPHEMY LAWS IN THE 21ST CENTURY A VIOLATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN PAKISTAN By Fanny Mazna A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in the field of Mass Communication and Media Arts Approved by: William Babcock, Co-Chair William Freivogel, Co-Chair Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale April, 6th 2017 AN ABSTRACT OF THE RESEARCH PAPER OF FANNY MAZNA, for the Master of Science degree in MASS COMMUNICATION AND MEDIA ARTS presented on APRIL, 6th 2017, at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. TITLE: BLASPHEMY LAWS IN THE 21ST CENTURY- A VIOLATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN PAKISTAN MAJOR PROFESSOR: Dr. -

Malta Is a Small, Densely-Populated Island Nation of 450,000 Inhabitants, Located in the Mediterranean Sea, South of Sicily

Malta Malta is a small, densely-populated island nation of 450,000 inhabitants, located in the Mediterranean Sea, south of Sicily. It is a parliamentary republic and member state of the European Union. Despite opposition from the Catholic Church, which remains hugely influential, Malta has seen significant progressive reforms in recent years including the introduction of divorce and same-sex civil unions, and the abolition of the country’s “blasphemy” law. Constitution and Education and Family, Freedom of government children’s rights community, expression society, religious advocacy of courts and humanist values tribunals There is There is state Discriminatory systematic funding of at least prominence is religious privilege some religious given to religious Preferential schools bodies, traditions treatment is given Religious schools or leaders to a religion or have powers to Religious groups religion in general discriminate in control some There is an admissions or public or social established employment services church or state religion State-funding of religious institutions or salaries, or discriminatory tax exemptions Constitution and Education and Family, Freedom of government children’s rights community, expression society, religious advocacy of courts and humanist values tribunals Official symbolic Concerns that deference to secular or religion religious authorities interfere in specifically religious freedoms Legend Constitution and government Freedom of conscience, religion, and expression are protected in law (Articles 40 and 41, Constitution of Malta). However, in practice, strong preference is afforded to the Roman Catholic Church, and Catholicism remains the official state religion of Malta (Article 2). Education and children’s rights The constitution prescribes religious teaching of the Catholic faith as compulsory education in all State schools: Article 2: (1) The religion of Malta is the Roman Catholic Apostolic Religion. -

Transcendence of God

TRANSCENDENCE OF GOD A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE OLD TESTAMENT AND THE QUR’AN BY STEPHEN MYONGSU KIM A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR (PhD) IN BIBLICAL AND RELIGIOUS STUDIES IN THE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA SUPERVISOR: PROF. DJ HUMAN CO-SUPERVISOR: PROF. PGJ MEIRING JUNE 2009 © University of Pretoria DEDICATION To my love, Miae our children Yein, Stephen, and David and the Peacemakers around the world. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I thank God for the opportunity and privilege to study the subject of divinity. Without acknowledging God’s grace, this study would be futile. I would like to thank my family for their outstanding tolerance of my late studies which takes away our family time. Without their support and kind endurance, I could not have completed this prolonged task. I am grateful to the staffs of University of Pretoria who have provided all the essential process of official matter. Without their kind help, my studies would have been difficult. Many thanks go to my fellow teachers in the Nairobi International School of Theology. I thank David and Sarah O’Brien for their painstaking proofreading of my thesis. Furthermore, I appreciate Dr Wayne Johnson and Dr Paul Mumo for their suggestions in my early stage of thesis writing. I also thank my students with whom I discussed and developed many insights of God’s relationship with mankind during the Hebrew Exegesis lectures. I also remember my former teachers from Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, especially from the OT Department who have shaped my academic stand and inspired to pursue the subject of this thesis. -

Blasphemy, Charlie Hebdo, and the Freedom of Belief and Expression

Blasphemy, Charlie Hebdo, and the Freedom of Belief and Expression The Paris attacks and the reactions rashad ali The horrific events in Paris, with the killing of a group of Other reactions highlight and emphasise the fact journalists, a Police officer, and members of the Jewish that Muslims are also victims of terrorism – often the community in France have shocked and horrified most main victims – a point which Charlie Hebdo made in commentators. These atrocities, which the Yemen branch an editorial of the first issue of the magazine published of the global terrorist group al-Qaeda have claimed the following the attack on its staff. Still others highlight responsibility for,1 have led to condemnations from that Jews were targeted merely because they were Jews.2 across the political spectrum and across religious divides. This was even more relevant given how a BBC journalist Some ubiquitous slogans that have arisen, whether appeared to suggest that there was a connection between Je suis Charlie, Ahmed, or Juif, have been used to show how “Jews” treated Palestinians in Israel and the killing of empathy with various victims of these horrid events. Jews in France in a kosher shop.3 These different responses illustrate some of the divides in The most notorious response arguably has not come public reaction, with solidarity shown to various camps. from Islamist circles but from the French neo-fascist For example, some have wished to show support and comedian Dieudonne for stating on his Facebook solidarity with the victims but have not wished to imply account “je me sens Charlie Coulibaly” (“I feel like Charlie or show support to Charlie Hebdo as a publication, Coulibaly”). -

Islam in a Secular State Walid Jumblatt Abdullah Islam in a Secular State

RELIGION AND SOCIETY IN ASIA Abdullah Islam in a Secular State a Secular in Islam Walid Jumblatt Abdullah Islam in a Secular State Muslim Activism in Singapore Islam in a Secular State Religion and Society in Asia This series contributes cutting-edge and cross-disciplinary academic research on various forms and levels of engagement between religion and society that have developed in the regions of South Asia, East Asia, and South East Asia, in the modern period, that is, from the early 19th century until the present. The publications in this series should reflect studies of both religion in society and society in religion. This opens up a discursive horizon for a wide range of themes and phenomena: the politics of local, national and transnational religion; tension between private conviction and the institutional structures of religion; economical dimensions of religion as well as religious motives in business endeavours; issues of religion, law and legality; gender relations in religious thought and practice; representation of religion in popular culture, including the mediatisation of religion; the spatialisation and temporalisation of religion; religion, secularity, and secularism; colonial and post-colonial construction of religious identities; the politics of ritual; the sociological study of religion and the arts. Engaging these themes will involve explorations of the concepts of modernity and modernisation as well as analyses of how local traditions have been reshaped on the basis of both rejecting and accepting Western religious, -

Statement by Dr. Richard Benkin

Dr. Richard L. Benkin ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Email: [email protected] http://www.InterfaithStrength.com Also Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn Bangladesh: “A rose by any other name is still blasphemy.” Written statement to US Commission on Religious Freedom Virtual Hearing on Blasphemy Laws and the Violation of International Religious Freedom Wednesday, December 9, 2020 Dr. Richard L. Benkin Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states: “Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.” While few people champion an unrestricted right to free of expression, fewer still stand behind the use of state power to protect a citizen’s right from being offended by another’s words. In the United States, for instance, a country regarded by many correctly or not as a “Christian” nation, people freely produce products insulting to many Christians, all protected, not criminalized by the government. A notorious example was a painting of the Virgin Mary with elephant dung in a 1999 Brooklyn Museum exhibit. Attempts to ban it or sanction the museum failed, and a man who later defaced the work to redress what he considered an anti-Christian slur was convicted of criminal mischief for it. Laws that criminalize free expression as blasphemy are incompatible with free societies, and nations that only pose as such often continue persecution for blasphemy in disguise. In Bangladesh, the government hides behind high sounding words in a toothless constitution while sanctioning blasphemy in other guises. -

"Blasphemy"? Jesus Before Caiaphas in Mark 14:61-64

CHAPTER ELEVEN IN WHAT SENSE "BLASPHEMY"? JESUS BEFORE CAIAPHAS IN MARK 14:61-64 Jesus' response to the question of Caiaphas, in which he affirms that he is "the Christ the Son of the Blessed," whom Caiaphas and company "will see" as "Son of Man seated at the right hand of Power and coming with the clouds of heaven" (Mark 14:61-62), provokes the cry of "blasphemy!" (Mark 14:64). Many scholars have wondered why, and for good reason. Claiming to be Israel's Messiah was not considered blasphemous.! Although disparaging them as impostors and opportun ists, Josephus never accused any of the many would-be kings and deliverers of first-century Israel as blasphemers. Perhaps a more telling example comes from rabbinic tradition. Rabbi Aqiba's procla mation of Simon ben Kosiba as Messiah was met with skepticism, but not with cries of blasphemy (cf. y. Ta'an. 4.5; b. Sanh. 93b.) Even W. L. Lane (The Gospel of Mark [NIC; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1974] 536) argues that "anyone who [was in prison and deserted by his followers, but nevertheless still] proclaimed himself to be the Messiah could not fail to be a blasphemer who dared to make a mockery of the promises given by God to his people." This is no more than an assumption. There is no evidence that a claim to be Messiah, under any circumstances, was considered blasphemous (pace J. C. O'Neill, "The Silence of Jesus," NTS 15 [1969] 153-67; idem, "The Charge of Blasphemy at Jesus' Trial before the Sanhedrin," in E. -

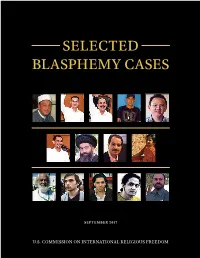

Selected Blasphemy Cases

SELECTED BLASPHEMY CASES SEPTEMBER 2017 U.S. COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM Mohamed Basuki “Ahok” Abdullah al-Nasr Andry Cahya Ahmed Musadeq Sebastian Joe Tjahaja Purnama EGYPT INDONESIA INDONESIA INDONESIA INDONESIA Ayatollah Mohammad Mahful Muis Kazemeini Mohammad Tumanurung Boroujerdi Ali Taheri Aasia Bibi INDONESIA IRAN IRAN PAKISTAN Ruslan Sokolovsky Abdul Shakoor RUSSIAN Raif Badawi Ashraf Fayadh Shankar Ponnam PAKISTAN FEDERATION SAUDI ARABIA SAUDI ARABIA SAUDI ARABIA UNITED STATES COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM SELECTED BLASPHEMY CASES SEPTEMBER 2017 WWW.USCIRF.GOV COMMISSIONERS Daniel Mark, Chairman Sandra Jolley, Vice Chair Kristina Arriaga de Bucholz, Vice Chair Tenzin Dorjee Clifford D. May Thomas J. Reese, S.J. John Ruskay Jackie Wolcott Erin D. Singshinsuk Executive Director PROFESSIONAL STAFF Dwight Bashir, Director of Research and Policy Elizabeth K. Cassidy, Director of International Law and Policy Judith E. Golub, Director of Congressional Affairs & Policy and Planning John D. Lawrence, Director of Communications Elise Goss-Alexander, Researcher Andrew Kornbluth, Policy Analyst Tiffany Lynch, Senior Policy Analyst Tina L. Mufford, Senior Policy Analyst Jomana Qaddour, Policy Analyst Karen Banno, Office Manager Roy Haskins, Manager of Finance and Administration Travis Horne, Communications Specialist SELECTED BLASPHEMY CASES Many countries today have blasphemy laws. Blasphemy is defined as “the act of insulting or showing contempt or lack of reverence for God.” Across the globe, billions of people view blasphemy as deeply offensive to their beliefs. Respecting Rights? Measuring the World’s • Violate international human rights standards; Blasphemy Laws, a U.S. Commission on Inter- • Often are vaguely worded, and few specify national Religious Freedom (USCIRF) report, or limit the forum in which blasphemy can documents the 71 countries – ranging from occur for purposes of punishment; Canada to Pakistan – that have blasphemy • Are inconsistent with the approach laws (as of June 2016). -

Cultural Dynamics

Cultural Dynamics http://cdy.sagepub.com/ Authoring (in)Authenticity, Regulating Religious Tolerance: The Implications of Anti-Conversion Legislation for Indian Secularism Jennifer Coleman Cultural Dynamics 2008 20: 245 DOI: 10.1177/0921374008096311 The online version of this article can be found at: http://cdy.sagepub.com/content/20/3/245 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Cultural Dynamics can be found at: Email Alerts: http://cdy.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://cdy.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://cdy.sagepub.com/content/20/3/245.refs.html >> Version of Record - Oct 21, 2008 What is This? Downloaded from cdy.sagepub.com at The University of Melbourne Libraries on April 11, 2014 AUTHORING (IN)AUTHENTICITY, REGULATING RELIGIOUS TOLERANCE The Implications of Anti-Conversion Legislation for Indian Secularism JENNIFER COLEMAN University of Pennsylvania ABSTRACT This article explores the politicization of ‘conversion’ discourses in contemporary India, focusing on the rising popularity of anti-conversion legislation at the individual state level. While ‘Freedom of Religion’ bills contend to represent the power of the Hindu nationalist cause, these pieces of legislation refl ect both the political mobility of Hindutva as a symbolic discourse and the prac- tical limits of its enforcement value within Indian law. This resurgence, how- ever, highlights the enduring nature of questions regarding the quality of ‘conversion’ as a ‘right’ of individuals and communities, as well as reigniting the ongoing battle over the line between ‘conversion’ and ‘propagation’. Ul- timately, I argue that, while the politics of conversion continue to represent a decisive point of reference in debates over the quality and substance of reli- gious freedom as a discernible right of Indian democracy and citizenship, the widespread negative consequences of this legislation’s enforcement remain to be seen. -

Blasphemy Law and Public Neutrality in Indonesia

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vol 8 No 2 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy March 2017 Research Article © 2017 Victor Imanuel W. Nalle. This is an open access article licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/). Blasphemy Law and Public Neutrality in Indonesia Victor Imanuel W. Nalle Faculty of Law, Darma Cendika Catholic University, Indonesia Doi:10.5901/mjss.2017.v8n2p57 Abstract Indonesia has the potential for social conflict and violence due to blasphemy. Currently, Indonesia has a blasphemy law that has been in effect since 1965. The blasphemy law formed on political factors and tend to ignore the public neutrality. Recently due to a case of blasphemy by the Governor of Jakarta, relevance of blasphemy law be discussed again. This paper analyzes the weakness of the blasphemy laws that regulated in Law No. 1/1965 and interpretation of the Constitutional Court on the Law No. 1/1965. The analysis in this paper, by statute approach, conceptual approach, and case approach, shows the weakness of Law No. 1/1965 in putting itself as an entity that is neutral in matters of religion. This weakness caused Law No. 1/1965 set the Government as the interpreter of the religion scriptures that potentially made the state can not neutral. Therefore, the criminalization of blasphemy should be based on criteria without involving the state as an interpreter of the theological doctrine. Keywords: constitutional right, blasphemy, religious interpretation, criminalization, public neutrality 1. Introduction Indonesia is a country with a high level of trust toward religion. -

Universal Periodic Review 2009

UNIVERSAL PERIODIC REVIEW 2009 SAUDI ARABIA NGO: European Centre for Law and Justice 4, Quai Koch 67000 Strasbourg France RELIGIOUS FREEDOM IN THE SAUDI ARABIA SECTION 1: Legal Framework I. Saudi Constitutional Provisions Saudi Arabia is an Islamic monarchy.1 The Saudi Constitution is comprised of the Koran, Sharia law, and the Basic Law.2 “Islamic law forms the basis for the country’s legal code.”3 Strict Islamic law governs,4 and as such, the Saudi Constitution does not permit religious freedom. Even the practice of Islam itself is limited to the strict, Saudi-specific interpretation of Islam.5 Importantly, the Saudi government makes essentially no distinction between religion and government.6 According to its constitution, Saudi Arabia is a monarchy with a limited Consultative Council and Council of Ministers.7 The Consultative Council is governed by the Shura Council Law, which is based on Islam,8 and serves as an advisory body that operates strictly within the traditional confines of Islamic law.9 The Council of Ministers, expressly recognized by the Basic Law,10 is authorized to “examine almost any matter in the kingdom.”11 The Basic Law was promulgated by the king in 1993 and operates somewhat like a limited “bill of rights” for Saudi citizens. Comprising a portion of the Saudi Constitution, the Basic Law broadly outlines “the government’s rights and responsibilities,” as well as the general structure of government and the general source of law (the Koran). 12 The Basic Law consists of 83 articles defining the strict, Saudi Islamic state. By declaring that Saudi Arabia is an Islamic state and by failing to make any 1 U.S.