Blasphemy Law and Public Neutrality in Indonesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BLASPHEMY LAWS in the 21ST CENTURY: a VIOLATION of HUMAN RIGHTS in PAKISTAN Fanny Mazna Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected]

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School 2017 BLASPHEMY LAWS IN THE 21ST CENTURY: A VIOLATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN PAKISTAN Fanny Mazna Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp Recommended Citation Mazna, Fanny. "BLASPHEMY LAWS IN THE 21ST CENTURY: A VIOLATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN PAKISTAN." (Jan 2017). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Papers by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BLASPHEMY LAWS IN THE 21ST CENTURY A VIOLATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN PAKISTAN by Fanny Mazna B.A., Kinnaird College for Women, 2014 A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Science Department of Mass Communication and Media Arts in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale May 2017 RESEARCH PAPER APPROVAL BLASPHEMY LAWS IN THE 21ST CENTURY A VIOLATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN PAKISTAN By Fanny Mazna A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in the field of Mass Communication and Media Arts Approved by: William Babcock, Co-Chair William Freivogel, Co-Chair Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale April, 6th 2017 AN ABSTRACT OF THE RESEARCH PAPER OF FANNY MAZNA, for the Master of Science degree in MASS COMMUNICATION AND MEDIA ARTS presented on APRIL, 6th 2017, at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. TITLE: BLASPHEMY LAWS IN THE 21ST CENTURY- A VIOLATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN PAKISTAN MAJOR PROFESSOR: Dr. -

Statement by Dr. Richard Benkin

Dr. Richard L. Benkin ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Email: [email protected] http://www.InterfaithStrength.com Also Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn Bangladesh: “A rose by any other name is still blasphemy.” Written statement to US Commission on Religious Freedom Virtual Hearing on Blasphemy Laws and the Violation of International Religious Freedom Wednesday, December 9, 2020 Dr. Richard L. Benkin Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states: “Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.” While few people champion an unrestricted right to free of expression, fewer still stand behind the use of state power to protect a citizen’s right from being offended by another’s words. In the United States, for instance, a country regarded by many correctly or not as a “Christian” nation, people freely produce products insulting to many Christians, all protected, not criminalized by the government. A notorious example was a painting of the Virgin Mary with elephant dung in a 1999 Brooklyn Museum exhibit. Attempts to ban it or sanction the museum failed, and a man who later defaced the work to redress what he considered an anti-Christian slur was convicted of criminal mischief for it. Laws that criminalize free expression as blasphemy are incompatible with free societies, and nations that only pose as such often continue persecution for blasphemy in disguise. In Bangladesh, the government hides behind high sounding words in a toothless constitution while sanctioning blasphemy in other guises. -

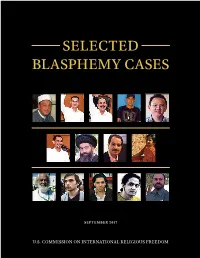

Selected Blasphemy Cases

SELECTED BLASPHEMY CASES SEPTEMBER 2017 U.S. COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM Mohamed Basuki “Ahok” Abdullah al-Nasr Andry Cahya Ahmed Musadeq Sebastian Joe Tjahaja Purnama EGYPT INDONESIA INDONESIA INDONESIA INDONESIA Ayatollah Mohammad Mahful Muis Kazemeini Mohammad Tumanurung Boroujerdi Ali Taheri Aasia Bibi INDONESIA IRAN IRAN PAKISTAN Ruslan Sokolovsky Abdul Shakoor RUSSIAN Raif Badawi Ashraf Fayadh Shankar Ponnam PAKISTAN FEDERATION SAUDI ARABIA SAUDI ARABIA SAUDI ARABIA UNITED STATES COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM SELECTED BLASPHEMY CASES SEPTEMBER 2017 WWW.USCIRF.GOV COMMISSIONERS Daniel Mark, Chairman Sandra Jolley, Vice Chair Kristina Arriaga de Bucholz, Vice Chair Tenzin Dorjee Clifford D. May Thomas J. Reese, S.J. John Ruskay Jackie Wolcott Erin D. Singshinsuk Executive Director PROFESSIONAL STAFF Dwight Bashir, Director of Research and Policy Elizabeth K. Cassidy, Director of International Law and Policy Judith E. Golub, Director of Congressional Affairs & Policy and Planning John D. Lawrence, Director of Communications Elise Goss-Alexander, Researcher Andrew Kornbluth, Policy Analyst Tiffany Lynch, Senior Policy Analyst Tina L. Mufford, Senior Policy Analyst Jomana Qaddour, Policy Analyst Karen Banno, Office Manager Roy Haskins, Manager of Finance and Administration Travis Horne, Communications Specialist SELECTED BLASPHEMY CASES Many countries today have blasphemy laws. Blasphemy is defined as “the act of insulting or showing contempt or lack of reverence for God.” Across the globe, billions of people view blasphemy as deeply offensive to their beliefs. Respecting Rights? Measuring the World’s • Violate international human rights standards; Blasphemy Laws, a U.S. Commission on Inter- • Often are vaguely worded, and few specify national Religious Freedom (USCIRF) report, or limit the forum in which blasphemy can documents the 71 countries – ranging from occur for purposes of punishment; Canada to Pakistan – that have blasphemy • Are inconsistent with the approach laws (as of June 2016). -

FAITH, INTOLERANCE, VIOLENCE and BIGOTRY Legal and Constitutional Issues of Freedom of Religion in Indonesia1 Adam J

DOI: 10.15642/JIIS.2016.10.2.181-212 Freedom of Religion in Indonesia FAITH, INTOLERANCE, VIOLENCE AND BIGOTRY Legal and Constitutional Issues of Freedom of Religion in Indonesia1 Adam J. Fenton London School of Public Relations, Jakarta - Indonesia | [email protected] Abstract: Religious intolerance and bigotry indeed is a contributing factor in social and political conflict including manifestations of terrorist violence. While freedom of religion is enshrined in ,ndonesia’s Constitution, social practices and governmental regulations fall short of constitutional and international law guarantees, allowing institutionalised bias in the treatment of religious minorities. Such bias inhiEits ,ndonesia’s transition to a fully-functioning pluralistic democracy and sacrifices democratic ideals of personal liberty and freedom of expression for the stated goals of religious and social harmony. The Ahok case precisely confirms that. The paper examines the constitutional bases of freedom of religion, ,ndonesia’s Blasphemy Law and takes account of the history and tenets of Pancasila which dictate a belief in God as the first principle of state ideology. The paper argues that the ,ndonesian state’s failure to recognise the legitimacy of alternate theological positions is a major obstacle to Indonesia recognising the ultimate ideal, enshrined in the national motto, of unity in diversity. Keywords: freedom of religion, violence, intolerance, constitution. Introduction This field of inquiry is where philosophy, religion, politics, terrorism–even scientific method–all converge in the arena of current 1 Based on a paper presented at the International Indonesia Forum IX, 23-24 August 2016 Atma Jaya Catholic University, Jakarta. JOURNAL OF INDONESIAN ISLAM Volume 10, Number 02, December 2016 181 Adam J. -

Blasphemy in a Secular State: Some Reflections

BLASPHEMY IN A SECULAR STATE: SOME REFLECTIONS Belachew Mekuria Fikre ♣ Abstract Anti-blasphemy laws have endured criticism in light of the modern, secular and democratic state system of our time. For example, Ethiopia’s criminal law provisions on blasphemous utterances, as well as on outrage to religious peace and feeling, have been maintained unaltered since they were enacted in 1957. However, the shift observed within the international human rights discourse tends to consider anti-blasphemy laws as going against freedom of expression. The recent Human Rights Committee General Comment No. 34 calls for a restrictive application of these laws for the full realisation of many of the rights within the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Secularism and human rights perspectives envisage legal protection to the believer and not the belief. Lessons can be drawn from the legal framework of defamation which considers injuries to the person rather than to institutions or to the impersonal sacred truth. It is argued that secular states can ‘promote reverence at the public level for private feelings’ through well-recognised laws of defamation and prohibition of hate speech rather than laws of blasphemy. This relocates the role of the state to its proper perspective in the context of its role in promoting interfaith dialogue, harmony and tolerance. Key words Blasphemy, Secular, Human Rights, Freedom of Expression, Defamation of Religion DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/mlr.v7i1.2 _____________ Introduction The secular as ‘an epistemic category’, and secularism as a value statement, have been around since the 1640s Peace of Westphalia, otherwise called the ‘peace of exhaustion’, and they remain one of the contested issues in today’s world political discourse. -

Measuring the World's Blasphemy Laws

RESPECTING RIGHTS? Measuring the World’s Blasphemy Laws U.S. COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM A gavel is seen in a hearing room in Panama City April 7, 2016. REUTERS/Carlos Jasso UNITED STATES COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM RESPECTING RIGHTS? Measuring the World’s Blasphemy Laws By Joelle Fiss and Jocelyn Getgen Kestenbaum JULY 2017 WWW.USCIRF.GOV COMMISSIONERS Daniel Mark, Chairman Sandra Jolley, Vice Chair Kristina Arriaga de Bucholz, Vice Chair Tenzin Dorjee Clifford D. May Thomas J. Reese, S.J. John Ruskay Jackie Wolcott Erin D. Singshinsuk Executive Director PROFESSIONAL STAFF Dwight Bashir, Director of Research and Policy Elizabeth K. Cassidy, Director of International Law and Policy Judith E. Golub, Director of Congressional Affairs & Policy and Planning John D. Lawrence, Director of Communications Sahar Chaudhry, Senior Policy Analyst Elise Goss-Alexander, Researcher Andrew Kornbluth, Policy Analyst Tiffany Lynch, Senior Policy Analyst Tina L. Mufford, Senior Policy Analyst Jomana Qaddour, Policy Analyst Karen Banno, Office Manager Roy Haskins, Manager of Finance and Administration Travis Horne, Communications Specialist This report, containing data collected, coded, and analyzed as of June 2016, was overseen by Elizabeth K. Cassidy, J.D., LL.M, Director of International Law and Policy at the U.S. Commis- sion on International Religious Freedom. At USCIRF, Elizabeth is a subject matter expert on international and comparative law issues related to religious freedom as well as U.S. refugee and asylum policy. -

The Impact of the Blasphemy Laws in Pakistan

“AS GOOD AS DEAD” THE IMPACT OF THE BLASPHEMY LAWS IN PAKISTAN Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Colin Foo © Amnesty International 2016 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2016 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 33/5136/2016 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS CASE SUMMARIES 7 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 9 1. THE EVOLUTION OF PAKISTAN’S BLASPHEMY LAWS 16 1.1 AMENDMENTS TO EXISTING LAW AND INTRODUCTION OF NEW LEGISLATION SINCE THE 1980S 17 1.2 SECTION 295-C AND THE FEDERAL SHARIAT COURT RULING 18 1.3 APPLICATION OF BLASPHEMY LAWS 18 2. THE BROAD SCOPE FOR ALLEGATIONS 21 2.1 BLASPHEMY ACCUSATIONS INSPIRED BY ULTERIOR MOTIVES 21 2.2 ACCUSATIONS OF BLASPHEMY AGAINST PEOPLE WITH MENTAL DISABILITIES 23 2.3 BLASPHEMY ACCUSATIONS USED TO CURTAIL FREEDOM OF OPINION AND EXPRESSION 24 3. -

Respecting Rights? Measuring the World's Blasphemy Laws

RESPECTING RIGHTS? Measuring the World’s Blasphemy Laws U.S. COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM A gavel is seen in a hearing room in Panama City April 7, 2016. REUTERS/Carlos Jasso UNITED STATES COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM RESPECTING RIGHTS? Measuring the World’s Blasphemy Laws By Joelle Fiss and Jocelyn Getgen Kestenbaum JULY 2017 WWW.USCIRF.GOV COMMISSIONERS Daniel Mark, Chairman Sandra Jolley, Vice Chair Kristina Arriaga de Bucholz, Vice Chair Tenzin Dorjee Clifford D. May Thomas J. Reese, S.J. John Ruskay Jackie Wolcott Erin D. Singshinsuk Executive Director PROFESSIONAL STAFF Dwight Bashir, Director of Research and Policy Elizabeth K. Cassidy, Director of International Law and Policy Judith E. Golub, Director of Congressional Affairs & Policy and Planning John D. Lawrence, Director of Communications Sahar Chaudhry, Senior Policy Analyst Elise Goss-Alexander, Researcher Andrew Kornbluth, Policy Analyst Tiffany Lynch, Senior Policy Analyst Tina L. Mufford, Senior Policy Analyst Jomana Qaddour, Policy Analyst Karen Banno, Office Manager Roy Haskins, Manager of Finance and Administration Travis Horne, Communications Specialist This report, containing data collected, coded, and analyzed as of June 2016, was overseen by Elizabeth K. Cassidy, J.D., LL.M, Director of International Law and Policy at the U.S. Commis- sion on International Religious Freedom. At USCIRF, Elizabeth is a subject matter expert on international and comparative law issues related to religious freedom as well as U.S. refugee and asylum policy. -

Policing Belief: the Impact of Blasphemy Laws on Human Rights Was Re- Searched and Written by Jo-Anne Prud’Homme, a Human Rights Researcher and Advocate

Policing Belief THE IMPACT OF BlAsphemy Laws On Human RIghts A FREEDOM HOUSE SPECIAL REPORT Policing Belief The Impact of BlAsphemy Laws On Human RIghts OCTOBER 2010 C O p y R i g h T i n f or m aT i O n All rights reserved. no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the pub- lisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. TaBlE Of contenTs Introduction. 1 Algeria. 13 Egypt . 21 greece . 35 Indonesia. 43 Malaysia. 57 Pakistan. 69 Poland. 89 References. 95 abouT freedOm hOusE Freedom House is an independent watchdog organization that supports the expansion of freedom around the world. Freedom House supports democratic change, monitors freedom, and advocates for democracy and human rights. Since its founding in 1941 by prominent Americans concerned with the mount- ing threats to peace and democracy, Freedom House has been a vigorous proponent of democratic values and a steadfast opponent of dictatorships of the far left and the far right. Eleanor Roosevelt and Wendell Willkie served as Freedom House’s first honorary co-chairpersons. Today, the organization’s diverse Board of Trustees is composed of a bipartisan mix of business and labor leaders, former senior government officials, scholars, and journalists who agree that the promotion of de- mocracy and human rights abroad is vital to America’s interests. aCknOwlEdgEmEnTs and sTudy team Policing Belief: The Impact of Blasphemy Laws on Human Rights was re- searched and written by Jo-anne prud’homme, a human rights researcher and advocate. -

Blasphemy Law in Muslim-Majority Countries: Religion-State Relationship and Rights Based Approaches in Pakistan, Indonesia and Turkey

Blasphemy Law in Muslim-Majority Countries: religion-state relationship and rights based approaches in Pakistan, Indonesia and Turkey By Haidar Adam Submitted to Central European University Department of Legal studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Law in Comparative Constitutional law Supervisor: Sejal Parmar CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2015 Abstract This thesis examines the blasphemy law within Muslim-majority countries in three jurisdictions namely Pakistan, Indonesia, and Turkey. Although it is very clear that the prohibition of blasphemy law is incompatible with international human rights law, the three insist its implementation. In addition, they also cooperate with other states to endorse the concept of “religion defamation”. However, the punishment pursuant to the blasphemy provisions is varies among the Muslim-majority countries depends on several factors. One of the factors is the religion-state relationship. Different forms of religion-state relationships will lead to different results in the state’s approach towards the religion. Within Muslim-majority states, there is wide range of interpretation of blasphemy provisions. The secular model in Muslim- majority states does not necessarily mean more protection for freedom of religion and freedom of expression. Keywords: blasphemy, defamation of religion, freedom of expression, constitution-making, religion-state relationship. CEU eTD Collection i Acknowledgements First of all, I would to thank to Allah SWT, because of His mercy I can finish this thesis. Peace be upon Muhammad, an Orphan, and also for his family. I would like to express my deep appreciation for my supervisor Professor Sejal Parmar for her patience encouraging me to finish this thesis and providing me many insightful comments and reviews. -

English Blasphemy

(QJOLVK%ODVSKHP\ Ian Hunter Humanity: An International Journal of Human Rights, Humanitarianism, and Development, Volume 4, Number 3, Winter 2013, pp. 403-428 (Article) 3XEOLVKHGE\8QLYHUVLW\RI3HQQV\OYDQLD3UHVV DOI: 10.1353/hum.2013.0022 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/hum/summary/v004/4.3.hunter.html Access provided by University of Queensland (12 Oct 2015 07:24 GMT) Ian Hunter English Blasphemy England’s blasphemy laws were abolished by an act of Parliament on May 8, 2008. This occurred with remarkably little fanfare, although not before a major parlia- mentary inquiry in 2002–3 and, prior to that, an attempt by a Muslim man (Mr. Choudhury) to launch a prosecution against Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses in 1990, on the grounds that it blasphemed against the Islamic religion.1 Interpretations of these developments have been strikingly different. Some commentators have viewed them as symptoms of the last gasps of a law whose enforcement of a national religion was an anachronism and whose replacement by offenses based on liberal toleration and respect was long overdue.2 Others, though, have seen the relegation of the protection of religion in favor of the protection of individual rights and freedoms as symptomatic of the West’s ‘‘intolerance of Europe’s Others’’ and ‘‘the secular modern state’s awesome potential for cruelty and destruction.’’3 In what follows I make a historical case for viewing these events neither as the triumph of rational liberalism over a confessional state nor as the tragic repression of an immigrant religious ‘‘Other’’ by a liberalism acting as the ideological bludgeon for the secular modern state.4 They should be viewed, rather, as part of the final undoing of the Anglican constitutional order that had lasted from the 1660s to the 1830s before undergoing a gradual disso- lution. -

Hate Speech Laws and Blasphemy Laws: Parallels Show Problems with the U.N

Emory International Law Review Volume 35 Issue 2 2021 Hate Speech Laws and Blasphemy Laws: Parallels Show Problems with the U.N. Strategy and Plan of Action on Hate Speech Meghan Fischer Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/eilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Meghan Fischer, Hate Speech Laws and Blasphemy Laws: Parallels Show Problems with the U.N. Strategy and Plan of Action on Hate Speech, 35 Emory Int'l L. Rev. 177 (2021). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/eilr/vol35/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Emory Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Emory International Law Review by an authorized editor of Emory Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FISCHER_3.22.21 3/23/2021 4:02 PM HATE SPEECH LAWS AND BLASPHEMY LAWS: PARALLELS SHOW PROBLEMS WITH THE U.N. STRATEGY AND PLAN OF ACTION ON HATE SPEECH Meghan Fischer* ABSTRACT In May 2019, the United Nations Secretary-General introduced the U.N. Strategy and Plan of Action on Hate Speech, an influential campaign that poses serious risks to religious and political minorities because its definition of hate speech parallels elements common to blasphemy laws. U.N. human rights entities have denounced blasphemy laws because they are vague, broad, and prone to arbitrary enforcement, enabling the authorities to use them to attack religious minorities, political opponents, and people who have minority viewpoints. Likewise, the Strategy and Plan of Action’s definition of hate speech is ambiguous and relies entirely on subjective interpretation, opening the door to arbitrary and malicious accusations and prosecutions.