Blasphemy and the Modern, “Secular” State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BLASPHEMY LAWS in the 21ST CENTURY: a VIOLATION of HUMAN RIGHTS in PAKISTAN Fanny Mazna Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected]

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School 2017 BLASPHEMY LAWS IN THE 21ST CENTURY: A VIOLATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN PAKISTAN Fanny Mazna Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp Recommended Citation Mazna, Fanny. "BLASPHEMY LAWS IN THE 21ST CENTURY: A VIOLATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN PAKISTAN." (Jan 2017). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Papers by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BLASPHEMY LAWS IN THE 21ST CENTURY A VIOLATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN PAKISTAN by Fanny Mazna B.A., Kinnaird College for Women, 2014 A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Science Department of Mass Communication and Media Arts in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale May 2017 RESEARCH PAPER APPROVAL BLASPHEMY LAWS IN THE 21ST CENTURY A VIOLATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN PAKISTAN By Fanny Mazna A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in the field of Mass Communication and Media Arts Approved by: William Babcock, Co-Chair William Freivogel, Co-Chair Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale April, 6th 2017 AN ABSTRACT OF THE RESEARCH PAPER OF FANNY MAZNA, for the Master of Science degree in MASS COMMUNICATION AND MEDIA ARTS presented on APRIL, 6th 2017, at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. TITLE: BLASPHEMY LAWS IN THE 21ST CENTURY- A VIOLATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN PAKISTAN MAJOR PROFESSOR: Dr. -

Islam in a Secular State Walid Jumblatt Abdullah Islam in a Secular State

RELIGION AND SOCIETY IN ASIA Abdullah Islam in a Secular State a Secular in Islam Walid Jumblatt Abdullah Islam in a Secular State Muslim Activism in Singapore Islam in a Secular State Religion and Society in Asia This series contributes cutting-edge and cross-disciplinary academic research on various forms and levels of engagement between religion and society that have developed in the regions of South Asia, East Asia, and South East Asia, in the modern period, that is, from the early 19th century until the present. The publications in this series should reflect studies of both religion in society and society in religion. This opens up a discursive horizon for a wide range of themes and phenomena: the politics of local, national and transnational religion; tension between private conviction and the institutional structures of religion; economical dimensions of religion as well as religious motives in business endeavours; issues of religion, law and legality; gender relations in religious thought and practice; representation of religion in popular culture, including the mediatisation of religion; the spatialisation and temporalisation of religion; religion, secularity, and secularism; colonial and post-colonial construction of religious identities; the politics of ritual; the sociological study of religion and the arts. Engaging these themes will involve explorations of the concepts of modernity and modernisation as well as analyses of how local traditions have been reshaped on the basis of both rejecting and accepting Western religious, -

Statement by Dr. Richard Benkin

Dr. Richard L. Benkin ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Email: [email protected] http://www.InterfaithStrength.com Also Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn Bangladesh: “A rose by any other name is still blasphemy.” Written statement to US Commission on Religious Freedom Virtual Hearing on Blasphemy Laws and the Violation of International Religious Freedom Wednesday, December 9, 2020 Dr. Richard L. Benkin Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states: “Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.” While few people champion an unrestricted right to free of expression, fewer still stand behind the use of state power to protect a citizen’s right from being offended by another’s words. In the United States, for instance, a country regarded by many correctly or not as a “Christian” nation, people freely produce products insulting to many Christians, all protected, not criminalized by the government. A notorious example was a painting of the Virgin Mary with elephant dung in a 1999 Brooklyn Museum exhibit. Attempts to ban it or sanction the museum failed, and a man who later defaced the work to redress what he considered an anti-Christian slur was convicted of criminal mischief for it. Laws that criminalize free expression as blasphemy are incompatible with free societies, and nations that only pose as such often continue persecution for blasphemy in disguise. In Bangladesh, the government hides behind high sounding words in a toothless constitution while sanctioning blasphemy in other guises. -

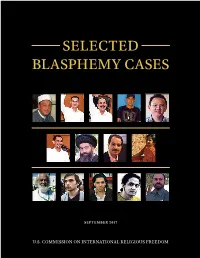

Selected Blasphemy Cases

SELECTED BLASPHEMY CASES SEPTEMBER 2017 U.S. COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM Mohamed Basuki “Ahok” Abdullah al-Nasr Andry Cahya Ahmed Musadeq Sebastian Joe Tjahaja Purnama EGYPT INDONESIA INDONESIA INDONESIA INDONESIA Ayatollah Mohammad Mahful Muis Kazemeini Mohammad Tumanurung Boroujerdi Ali Taheri Aasia Bibi INDONESIA IRAN IRAN PAKISTAN Ruslan Sokolovsky Abdul Shakoor RUSSIAN Raif Badawi Ashraf Fayadh Shankar Ponnam PAKISTAN FEDERATION SAUDI ARABIA SAUDI ARABIA SAUDI ARABIA UNITED STATES COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM SELECTED BLASPHEMY CASES SEPTEMBER 2017 WWW.USCIRF.GOV COMMISSIONERS Daniel Mark, Chairman Sandra Jolley, Vice Chair Kristina Arriaga de Bucholz, Vice Chair Tenzin Dorjee Clifford D. May Thomas J. Reese, S.J. John Ruskay Jackie Wolcott Erin D. Singshinsuk Executive Director PROFESSIONAL STAFF Dwight Bashir, Director of Research and Policy Elizabeth K. Cassidy, Director of International Law and Policy Judith E. Golub, Director of Congressional Affairs & Policy and Planning John D. Lawrence, Director of Communications Elise Goss-Alexander, Researcher Andrew Kornbluth, Policy Analyst Tiffany Lynch, Senior Policy Analyst Tina L. Mufford, Senior Policy Analyst Jomana Qaddour, Policy Analyst Karen Banno, Office Manager Roy Haskins, Manager of Finance and Administration Travis Horne, Communications Specialist SELECTED BLASPHEMY CASES Many countries today have blasphemy laws. Blasphemy is defined as “the act of insulting or showing contempt or lack of reverence for God.” Across the globe, billions of people view blasphemy as deeply offensive to their beliefs. Respecting Rights? Measuring the World’s • Violate international human rights standards; Blasphemy Laws, a U.S. Commission on Inter- • Often are vaguely worded, and few specify national Religious Freedom (USCIRF) report, or limit the forum in which blasphemy can documents the 71 countries – ranging from occur for purposes of punishment; Canada to Pakistan – that have blasphemy • Are inconsistent with the approach laws (as of June 2016). -

Cultural Dynamics

Cultural Dynamics http://cdy.sagepub.com/ Authoring (in)Authenticity, Regulating Religious Tolerance: The Implications of Anti-Conversion Legislation for Indian Secularism Jennifer Coleman Cultural Dynamics 2008 20: 245 DOI: 10.1177/0921374008096311 The online version of this article can be found at: http://cdy.sagepub.com/content/20/3/245 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Cultural Dynamics can be found at: Email Alerts: http://cdy.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://cdy.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://cdy.sagepub.com/content/20/3/245.refs.html >> Version of Record - Oct 21, 2008 What is This? Downloaded from cdy.sagepub.com at The University of Melbourne Libraries on April 11, 2014 AUTHORING (IN)AUTHENTICITY, REGULATING RELIGIOUS TOLERANCE The Implications of Anti-Conversion Legislation for Indian Secularism JENNIFER COLEMAN University of Pennsylvania ABSTRACT This article explores the politicization of ‘conversion’ discourses in contemporary India, focusing on the rising popularity of anti-conversion legislation at the individual state level. While ‘Freedom of Religion’ bills contend to represent the power of the Hindu nationalist cause, these pieces of legislation refl ect both the political mobility of Hindutva as a symbolic discourse and the prac- tical limits of its enforcement value within Indian law. This resurgence, how- ever, highlights the enduring nature of questions regarding the quality of ‘conversion’ as a ‘right’ of individuals and communities, as well as reigniting the ongoing battle over the line between ‘conversion’ and ‘propagation’. Ul- timately, I argue that, while the politics of conversion continue to represent a decisive point of reference in debates over the quality and substance of reli- gious freedom as a discernible right of Indian democracy and citizenship, the widespread negative consequences of this legislation’s enforcement remain to be seen. -

Blasphemy Law and Public Neutrality in Indonesia

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vol 8 No 2 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy March 2017 Research Article © 2017 Victor Imanuel W. Nalle. This is an open access article licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/). Blasphemy Law and Public Neutrality in Indonesia Victor Imanuel W. Nalle Faculty of Law, Darma Cendika Catholic University, Indonesia Doi:10.5901/mjss.2017.v8n2p57 Abstract Indonesia has the potential for social conflict and violence due to blasphemy. Currently, Indonesia has a blasphemy law that has been in effect since 1965. The blasphemy law formed on political factors and tend to ignore the public neutrality. Recently due to a case of blasphemy by the Governor of Jakarta, relevance of blasphemy law be discussed again. This paper analyzes the weakness of the blasphemy laws that regulated in Law No. 1/1965 and interpretation of the Constitutional Court on the Law No. 1/1965. The analysis in this paper, by statute approach, conceptual approach, and case approach, shows the weakness of Law No. 1/1965 in putting itself as an entity that is neutral in matters of religion. This weakness caused Law No. 1/1965 set the Government as the interpreter of the religion scriptures that potentially made the state can not neutral. Therefore, the criminalization of blasphemy should be based on criteria without involving the state as an interpreter of the theological doctrine. Keywords: constitutional right, blasphemy, religious interpretation, criminalization, public neutrality 1. Introduction Indonesia is a country with a high level of trust toward religion. -

FAITH, INTOLERANCE, VIOLENCE and BIGOTRY Legal and Constitutional Issues of Freedom of Religion in Indonesia1 Adam J

DOI: 10.15642/JIIS.2016.10.2.181-212 Freedom of Religion in Indonesia FAITH, INTOLERANCE, VIOLENCE AND BIGOTRY Legal and Constitutional Issues of Freedom of Religion in Indonesia1 Adam J. Fenton London School of Public Relations, Jakarta - Indonesia | [email protected] Abstract: Religious intolerance and bigotry indeed is a contributing factor in social and political conflict including manifestations of terrorist violence. While freedom of religion is enshrined in ,ndonesia’s Constitution, social practices and governmental regulations fall short of constitutional and international law guarantees, allowing institutionalised bias in the treatment of religious minorities. Such bias inhiEits ,ndonesia’s transition to a fully-functioning pluralistic democracy and sacrifices democratic ideals of personal liberty and freedom of expression for the stated goals of religious and social harmony. The Ahok case precisely confirms that. The paper examines the constitutional bases of freedom of religion, ,ndonesia’s Blasphemy Law and takes account of the history and tenets of Pancasila which dictate a belief in God as the first principle of state ideology. The paper argues that the ,ndonesian state’s failure to recognise the legitimacy of alternate theological positions is a major obstacle to Indonesia recognising the ultimate ideal, enshrined in the national motto, of unity in diversity. Keywords: freedom of religion, violence, intolerance, constitution. Introduction This field of inquiry is where philosophy, religion, politics, terrorism–even scientific method–all converge in the arena of current 1 Based on a paper presented at the International Indonesia Forum IX, 23-24 August 2016 Atma Jaya Catholic University, Jakarta. JOURNAL OF INDONESIAN ISLAM Volume 10, Number 02, December 2016 181 Adam J. -

Social Geography-18Kp2g07

SOCIAL GEOGRAPHY CODE – 18KP2GO7 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ UNIT- I SOCIAL GEOGRAPHY: NATURE AND SCOPE OF SOCIAL GEOGRAPHY-SOCIAL STRUCTURE-SOCIAL PROCESSES --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Social geography • The term ‘social geography’ carries with it an inherent confusion. In the popular perception the distinction between social and cultural geography is not very clear. The idea which has gained popularity with the geographers is that social geography is an analysis of social phenomena expressed in space. When the term emerged within the Anglo-American tradition during the 1960s, it was basically applied as a synonym for the search for patterns in the distribution of social groups. • Social geography is the branch of human geography that is most closely related to social theory in general and sociology in particular, dealing with the relation of social phenomena and its spatial components. Though the term itself has a tradition of more than 100 years,[ there is no consensus • However, the term ‘ social phenomena’ is in its developing stage and might be interpreted in a variety of ways keeping in view the specific context of the societies at different stages of social evolution in the occidental and the oriental worlds. The term ‘social phenomena’ encompasses the whole framework of human interaction with environment, leading to the articulation of social space by diverse human groups in different ways. • The end-product of human activity may be perceived in the spatial patterns manifest in the personality of regions; each pattern acquiring its form under the overwhelming influence of social structure. Besides the patterns, the way the social phenomena are expressed in space may become a cause of concern as well. -

Redalyc.Myths and Realities on Islam and Democracy in the Middle East

Estudios Políticos ISSN: 0121-5167 [email protected] Instituto de Estudios Políticos Colombia Cevik, Salim Myths and Realities on Islam and Democracy in the Middle East Estudios Políticos, núm. 38, enero-junio, 2011, pp. 121-144 Instituto de Estudios Políticos Medellín, Colombia Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=16429066007 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Myths and Realities on Islam and Democracy in the Middle East* Salim Cevik** Abstract There is a strong body of literature that claims that Islam and democracy are essentially incompatible. However, Islam like all other religions is multivocal and it has strong theorethical elements that can also work for a basis of a democratic polity. Throughout the Muslim world there are certain countries that achieved a considerable level of democratization. It is only the Arab world, not the Muslim world, that so far represents a complete failure in terms of democratic transition. The failure of Arab world should be attributed to more political reasons, such as oil economy and the rentier state model than to Islam. Lack of international support for pro-democracy movements in the region, under the fear that they might move towards an Islamist political system is also an important factor in the democratic failures in the region. However, democratic record of Turkey’s pro-Islamic Justice and Development Party challenges these fears. With the international attention it attracts, particularly from the Arab world, Turkish experience provides a strong case for the compatibility of [ 121 ] democracy and Islam. -

Blasphemy in a Secular State: Some Reflections

BLASPHEMY IN A SECULAR STATE: SOME REFLECTIONS Belachew Mekuria Fikre ♣ Abstract Anti-blasphemy laws have endured criticism in light of the modern, secular and democratic state system of our time. For example, Ethiopia’s criminal law provisions on blasphemous utterances, as well as on outrage to religious peace and feeling, have been maintained unaltered since they were enacted in 1957. However, the shift observed within the international human rights discourse tends to consider anti-blasphemy laws as going against freedom of expression. The recent Human Rights Committee General Comment No. 34 calls for a restrictive application of these laws for the full realisation of many of the rights within the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Secularism and human rights perspectives envisage legal protection to the believer and not the belief. Lessons can be drawn from the legal framework of defamation which considers injuries to the person rather than to institutions or to the impersonal sacred truth. It is argued that secular states can ‘promote reverence at the public level for private feelings’ through well-recognised laws of defamation and prohibition of hate speech rather than laws of blasphemy. This relocates the role of the state to its proper perspective in the context of its role in promoting interfaith dialogue, harmony and tolerance. Key words Blasphemy, Secular, Human Rights, Freedom of Expression, Defamation of Religion DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/mlr.v7i1.2 _____________ Introduction The secular as ‘an epistemic category’, and secularism as a value statement, have been around since the 1640s Peace of Westphalia, otherwise called the ‘peace of exhaustion’, and they remain one of the contested issues in today’s world political discourse. -

Measuring the World's Blasphemy Laws

RESPECTING RIGHTS? Measuring the World’s Blasphemy Laws U.S. COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM A gavel is seen in a hearing room in Panama City April 7, 2016. REUTERS/Carlos Jasso UNITED STATES COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM RESPECTING RIGHTS? Measuring the World’s Blasphemy Laws By Joelle Fiss and Jocelyn Getgen Kestenbaum JULY 2017 WWW.USCIRF.GOV COMMISSIONERS Daniel Mark, Chairman Sandra Jolley, Vice Chair Kristina Arriaga de Bucholz, Vice Chair Tenzin Dorjee Clifford D. May Thomas J. Reese, S.J. John Ruskay Jackie Wolcott Erin D. Singshinsuk Executive Director PROFESSIONAL STAFF Dwight Bashir, Director of Research and Policy Elizabeth K. Cassidy, Director of International Law and Policy Judith E. Golub, Director of Congressional Affairs & Policy and Planning John D. Lawrence, Director of Communications Sahar Chaudhry, Senior Policy Analyst Elise Goss-Alexander, Researcher Andrew Kornbluth, Policy Analyst Tiffany Lynch, Senior Policy Analyst Tina L. Mufford, Senior Policy Analyst Jomana Qaddour, Policy Analyst Karen Banno, Office Manager Roy Haskins, Manager of Finance and Administration Travis Horne, Communications Specialist This report, containing data collected, coded, and analyzed as of June 2016, was overseen by Elizabeth K. Cassidy, J.D., LL.M, Director of International Law and Policy at the U.S. Commis- sion on International Religious Freedom. At USCIRF, Elizabeth is a subject matter expert on international and comparative law issues related to religious freedom as well as U.S. refugee and asylum policy. -

“Une Messe Est Possible”: the Imbroglio of the Catholic Church in Contemporary Latin Europe

Center for European Studies Working Paper No. 113 “Une Messe est Possible”: The Imbroglio of the Catholic Church 1 in Contemporary Latin Europe by Paul Christopher Manuel Margaret Mott [email protected] [email protected] Paul Christopher Manuel is Affiliate and Co-Chair, Iberian Study Group, Center for European Studies, Har- vard University and Professor and Chair, Department of Politics, Saint Anselm College. Margaret Mott is Assistant Professor of Political Science at Marlboro College. ABSTRACT Throughout the contemporary period, the Church-State relationship in the nation-states of France, Italy, Spain and Portugal – which we will refer to as Latin Europe in this paper – has been a lively source of political conflict and societal cleavage, both on epistemological, and ontological grounds. Epistemological, in that the person living in Latin Europe has to decide whether his world view will be religious or secular; ontological, in that his mortality has kept some sense of the Catholic religion close to his heart and soul at the critical moments of his human reality. Secular views tend to define the European during ordinary periods of life, (“métro boulot dodo,”) while religious beliefs surge during the extraordinary times of life (birth, marriage, death,) as well as during the traditional ceremonial times (Christmas, Easter). This paper will approach the ques- tion on the role of the Catholic church in contemporary Latin Europe by first proposing three models of church-state relations in the region and their historical development, then looking at the role of the Vatican, followed by an examination of some recent Eurobarometer data on the views of contemporary Catholics in each country, and finishing with an analysis of selected public pol- icy issues in each country.