Islamic Theological Texts and Contexts in Banjarese Society: an Overview of the Existing Studies*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

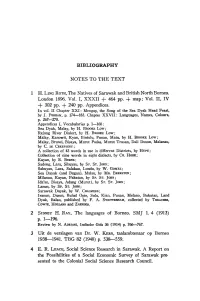

BIBLIOGRAPHY NOTES to the TEXT 1 H. LING ROTH, the Natives

BIBLIOGRAPHY NOTES TO THE TEXT 1 H. LING ROTH, The Natives of Sarawak and British North Borneo. London 18%. Vol. I, XXXII + 464 pp. + map; Vol. II, IV + 302 pp. + 240 pp. Appendices. In vol. II Chapter XXI: Mengap, the Song of the Sea Dyak Head Feast, by J. PERHAM, p. 174-183. Chapter XXVII: Languages, Names, Colours, p.267-278. Appendices I, Vocabularies p. 1-160: Sea Dyak, Malay, by H. BROOKE Low; Rejang River Dialect, by H. BROOKE Low; Malay, Kanowit, Kyan, Bintulu, Punan, Matu, by H. BROOKE Low; Malay, Brunei, Bisaya, Murut Padas, Murut Trusan, Dali Dusun, Malanau, by C. DE CRESPIGNY; A collection of 43 words in use in different Districts, by HUPE; Collection of nine words in eight dialects, by CH. HOSE; Kayan, by R. BURNS; Sadong, Lara, Sibuyau, by SP. ST. JOHN; Sabuyau, Lara, Salakau, Lundu, by W. GoMEZ; Sea Dayak (and Bugau), Malau, by MR. BRERETON; Milanau, Kayan, Pakatan, by SP. ST. JOHN; Ida'an, Bisaya, Adang (Murut), by SP. ST. JOlIN; Lanun, by SP. ST. JOHN; Sarawak Dayak, by W. CHALMERS; Iranun, Dusun, Bulud Opie, Sulu, Kian, Punan, Melano, Bukutan, Land Dyak, Balau, published by F. A. SWETTENHAM, collected by TREACHER, COWIE, HOLLAND and ZAENDER. 2 SIDNEY H. RAY, The languages of Borneo. SMJ 1. 4 (1913) p.1-1%. Review by N. ADRIANI, Indische Gids 36 (1914) p. 766-767. 3 Uit de verslagen van Dr. W. KERN, taalambtenaar op Borneo 1938-1941. TBG 82 (1948) p. 538---559. 4 E. R. LEACH, Social Science Research in Sarawak. A Report on the Possibilities of a Social Economic Survey of Sarawak pre sented to the Colonial Social Science Research Council. -

Learn Thai Language in Malaysia

Learn thai language in malaysia Continue Learning in Japan - Shinjuku Japan Language Research Institute in Japan Briefing Workshop is back. This time we are with Shinjuku of the Japanese Language Institute (SNG) to give a briefing for our students, on learning Japanese in Japan.You will not only learn the language, but you will ... Or nearby, the Thailand- Malaysia border. Almost one million Thai Muslims live in this subregion, which is a belief, and learn how, to grow other (besides rice) crops for which there is a good market; Thai, this term literally means visitor, ASEAN identity, are we there yet? Poll by Thai Tertiary Students ' Sociolinguistic. Views on the ASEAN community. Nussara Waddsorn. The Assumption University usually introduces and offers as a mandatory optional or free optional foreign language course in the state-higher Japanese, German, Spanish and Thai languages of Malaysia. In what part students find it easy or difficult to learn, taking Mandarin READING HABITS AND ATTITUDES OF THAI L2 STUDENTS from MICHAEL JOHN STRAUSS, presented partly to meet the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS (TESOL) I was able to learn Thai with Sukothai, where you can learn a lot about the deep history of Thailand and culture. Be sure to read the guide and learn a little about the story before you go. Also consider visiting neighboring countries like Cambodia, Vietnam and Malaysia. Air LANGUAGE: Thai, English, Bangkok TYPE OF GOVERNMENT: Constitutional Monarchy CURRENCY: Bath (THB) TIME ZONE: GMT No 7 Thailand invites you to escape into a world of exotic enchantment and excitement, from the Malaysian peninsula. -

Married Couples, Banjarese- Javanese Ethnics: a Case Study in South Kalimantan Province, Indonesia

Advances in Language and Literary Studies ISSN: 2203-4714 Vol. 7 No. 4; August 2016 Australian International Academic Centre, Australia Flourishing Creativity & Literacy An Analysis of Language Code Used by the Cross- Married Couples, Banjarese- Javanese Ethnics: A Case Study in South Kalimantan Province, Indonesia Supiani English Department, Teachers Training Faculty, Islamic University of Kalimantan Banjarmasin South Kalimantan Province, Indonesia E-mail: [email protected] Doi:10.7575/aiac.alls.v.7n.4p.139 Received: 02/04/2016 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.7575/aiac.alls.v.7n.4p.139 Accepted: 07/06/2016 Abstract This research aims to describe the use of language code applied by the participants and to find out the factors influencing the choice of language codes. This research is qualitative research that describe the use of language code in the cross married couples. The data are taken from the discourses about language code phenomena dealing with the cross- married couples, Banjarese- Javanese ethnics in Tanah Laut regency South Kalimantan, Indonesia. The conversations occur in the family and social life such as between a husband and a wife, a father and his son/daughter, a mother and her son/daughter, a husband and his friends, a wife and her neighbor, and so on. There are 23 data observed and recoded by the researcher based on a certain criteria. Tanah Laut regency is chosen as a purposive sample where this regency has many different ethnics so that they do cross cultural marriage for example between Banjarese- Javanese ethnics. Findings reveal that mostly the cross married couple used code mixing and code switching in their conversation of daily activities. -

The Conceptualization of Banjarese Culture Through Adjectives in Banjarese Lullabies

English Language Education Study Program, FKIP Universitas Lambung Mangkurat Banjarmasin Volume 2 Number 2 2019 THE CONCEPTUALIZATION OF BANJARESE CULTURE THROUGH ADJECTIVES IN BANJARESE LULLABIES Jumainah Abstract: The focus of this study is to conceptualize STKIP PGRI Banjarmasin Banjarese living values through the investigation of [email protected] adjectives used in Banjarese lullabies. Singing lullabies while rocking the baby is a common practice for Agustina Lestary Banjarese people. The lullabies becoming the subject of STKIP PGRI Banjarmasin the study of this research are the ones with Banjarese [email protected] lyrics. In practice, Banjarese parents do not only sing lullabies in their tribe language but also in either Arabic Ninuk Krismanti or Indonesian. The data are collected through three STKIP PGRI Banjarmasin techniques: observation, interview, and documentation. [email protected] The data are obtained from five regions all over South Kalimantan to represent both Banjar Hulu and Banjar Kuala. The adjectives found the lullabies being investigated are analyzed using Cultural Linguistic approach. The results of the study show a close connection between adjectives used in the lullabies and beliefs of Banjarese people. Adjectives describing desired and undesired traits of children reflect Islamic teachings. Keywords: Banjarese lullabies, conceptualization, Cultural Linguistics INTRODUCTION The definition of culture should not be limited only to particular performances, traditional dresses or ceremonies. Culture of a society is embedded in its people’s everyday lifestyle. The wisdom of a culture and the communal beliefs and thought are portrayed by how the people live, including but not limited to how they use their language. Language is tranformed to different channels, including lyrics of songs. -

A Phylogenetic Approach to Comparative Linguistics: a Test Study Using the Languages of Borneo

Hirzi Luqman 1st September 2010 A Phylogenetic Approach to Comparative Linguistics: a Test Study using the Languages of Borneo Abstract The conceptual parallels between linguistic and biological evolution are striking; languages, like genes are subject to mutation, replication, inheritance and selection. In this study, we explore the possibility of applying phylogenetic techniques established in biology to linguistic data. Three common phylogenetic reconstruction methods are tested: (1) distance-based network reconstruction, (2) maximum parsimony and (3) Bayesian inference. We use network analysis as a preliminary test to inspect degree of horizontal transmission prior to the use of the other methods. We test each method for applicability and accuracy, and compare their results with those from traditional classification. We find that the maximum parsimony and Bayesian inference methods are both very powerful and accurate in their phylogeny reconstruction. The maximum parsimony method recovered 8 out of a possible 13 clades identically, while the Bayesian inference recovered 7 out of 13. This match improved when we considered only fully resolved clades for the traditional classification, with maximum parsimony scoring 8 out of 9 possible matches, and Bayesian 7 out of 9 matches. Introduction different dialects and languages. And just as phylogenetic inference may be muddied by horizontal transmission, so “The formation of different languages and of distinct too may borrowing and imposition cloud true linguistic species, and the proofs that both have been developed relations. These fundamental similarities in biological and through a gradual process, are curiously parallel... We find language evolution are obvious, but do they imply that tools in distinct languages striking homologies due to community and methods developed in one field are truly transferable to of descent, and analogies due to a similar process of the other? Or are they merely clever and coincidental formation.. -

De La Versatilité (5) Avatars Du Luth Gambus À Bornéo

De la versatilité (5) Avatars du luth Gambus à Bornéo D HEROUVILLE, Pierre Draft 2013-13.0 - Mars 2020 Résumé : le présent article a pour objet l’origine et la diffusion des luths monoxyles en Malaisie et en Indonésie, en se focalisant sur l’histoire des genres musicaux locaux. Mots clés : diaspora hadhrami, qanbus, gambus, gambus Banjar, gambus Brunei, panting, tingkilan, jogget gembira, marwas, mamanda, rantauan, zapin, kutai, bugis CHAPITRE 5 : LE GAMBUS A BORNEO L.F. HILARIAN s’est évertué à dater la diffusion chez les premiers malais du luth iranien Barbat , ou de son avatar supposé yéménite Qanbus vers les débuts de l’islam. En l’absence d’annales explicites sur l’instrument, sa recherche a constamment corrélé historiquement diffusion de l’Islam à introduction de l’instrument. Dans le cas de Bornéo Isl, [RASHID, 2010] cite néanmoins l’instrument dans l’apparat du sultan (Awang) ALAK BELATAR (d.1371 AD?), à une époque avérée de l’islamisation de Brunei par le sultanat de Johore. Or, le qanbus yéménite aurait probablement été (ré)introduit à Lamu, Zanzibar, en Malaisie et aux Comores par une vague d’émigration hadhramie tardive, ce qui n’exclut pas cette présence sporadique antérieure. Nous n’étayons cette hypothèse sur la relative constance organologique et dimensionnelle des instruments à partir du 19ème siècle. L’introduction dans ces contrées de la danse al-zafan et du tambour marwas, tous fréquemment associés au qanbus, indique également qu’il a été introduit comme un genre autant que comme un instrument. Nous inventorions la lutherie et les genres relatifs dans l’île de Bornéo. -

[.35 **Natural Language Processing Class Here Computational Linguistics See Manual at 006.35 Vs

006 006 006 DeweyiDecimaliClassification006 006 [.35 **Natural language processing Class here computational linguistics See Manual at 006.35 vs. 410.285 *Use notation 019 from Table 1 as modified at 004.019 400 DeweyiDecimaliClassification 400 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 [400 [400 *‡Language Class here interdisciplinary works on language and literature For literature, see 800; for rhetoric, see 808. For the language of a specific discipline or subject, see the discipline or subject, plus notation 014 from Table 1, e.g., language of science 501.4 (Option A: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, class in 410, where full instructions appear (Option B: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, place before 420 through use of a letter or other symbol. Full instructions appear under 420–490) 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 SUMMARY [401–409 Standard subdivisions and bilingualism [410 Linguistics [420 English and Old English (Anglo-Saxon) [430 German and related languages [440 French and related Romance languages [450 Italian, Dalmatian, Romanian, Rhaetian, Sardinian, Corsican [460 Spanish, Portuguese, Galician [470 Latin and related Italic languages [480 Classical Greek and related Hellenic languages [490 Other languages 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [401 *‡Philosophy and theory See Manual at 401 vs. 121.68, 149.94, 410.1 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [.3 *‡International languages Class here universal languages; general -

Judul : an Analysis of Language Code Used by the Cross Married Couple

Judul : An analysis of language code used by the cross married couple, banjarese- Javanese ethnic group (a case study in pelaihari regency south Kalimantan) Nama : Supiani CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A. Research Background People use language to communicate in their every day social interactions. Thus, language becomes an important medium of communication. In communication, language makes people easier to express their thoughts, feelings, experiences, and so on. Wardhaugh (1998: 8) explains that, “language allows people to say things to each other and express communicative needs”. In short, language is constantly used by humans in their every day life. Many linguists have tried to make definitions of language. According to Hall (in Lyons, 1981: 4) “Language is the institution whereby humans communicate and interact with each other by means of habitually used oral- auditory arbitrary symbol”. Meanwhile in language: The Social Mirror, Chaika (1994: 6) states: “Language is multi layered and does not show a one-to-one correspondence between message and meaning as animal languages do. For this reason, every meaning can be expressed in more than one way and there are many ways to express any meaning. Languages differ from each other, but all seem suited for the tasks they are used for. Languages change with changing social conditions”. 2 In all human activities, the language use has an important correlation with the factors outside of it. People commonly use language in accordance with social structure and system of value in the society. The internal and external differences in human societies such as sex, age, class, occupation, geographical origin and so on, also influence their language1 . -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research (ASSEHR), volume 147 1st International Conference on Social Sciences Education "Multicultural Transformation in Education, Social Sciences and Wetland Environment" (ICSSE 2017) Exploring Cultural Values Through Banjarese Language Study Zulkifli Indonesia Language Education Department Faculty of Teacher Training and Education Universitas Lambung Mangkurat Banjarmasin, Indonesia [email protected] Abstract— Culture as a human creation is constantly evolving, culture itself. Essentially, humans do not want to survive in as well as experiencing change, along with the dynamics of the certain circumstances, but they want to go to better conditions, life of its supporting people. Every culture has some cultural more pleasant circumstances, and circumstances that further values that become a part of the wisdom of its people. These ensure the survival of their lives and the next generation. values can be found through language as an important element in One element of culture that is also highly regarded by the culture. Therefore, the study of language is important if supporting society is the language with all things related in it, associated with the exploration of cultural values in a society. It also applies to the study of Banjarese cultural values. The study including those concerning cultural values. In other words, the of Banjarase language can be used to the language use, through assessment of the language will be able to uncover the cultural sentences, both revealed through the use of the language in the values that apply in the language itself. Indeed, it must be association, as well as in the use of the language that goes into the admitted that language is a reflection of people's lives literary field. -

BANJARESE ETHNO-RELIGIOUS IDENTITY MAINTENANCE THROUGH the REINTRODUCTION of BANJAR JAWI SCRIPT Saifuddin Ahmad Husin

1 BANJARESE ETHNO-RELIGIOUS IDENTITY MAINTENANCE THROUGH THE REINTRODUCTION OF BANJAR JAWI SCRIPT Saifuddin Ahmad Husin Abstract Language sociologists propose some factors contributing to the choice of a language over the other. These factors include economic, social, political, educational, and demographic factors. Other language scientists mention religious, values and attitudinal factors. What is real choice is there for those who use lesser-used script, such as Arabic script for Malay and Bahasa Indonesia, in a community where most people use a major national script, i.e. Latin script to write their language. How do economic, political, religious, educational, and demographic factors influence the choice of use of script for a language? Introduction Sociolinguists suggest that there are many different social reasons for choosing a particular code or variety in a community where various language or code choices are available. When discussing about language choice and its results; language shift and language maintenance, sociolinguists mostly speak about choosing a whole system and structure of language. Seldom, if never at all, have they discussed it with respect to the script in which a language is written. Therefore, research on use of script has been a scarcity in the field of sociolinguistics. One of such scarcity has been the work of Christina Bratt Paulston (2003) which mentioned choice of alphabet as one of the major language problems. This study is about Arabic script used to write Banjarese language. Such script is usually known as Malay Arabic script or Jawi Script. The use of such script varies from place to place following the system and structure its respective language user. -

Language Shift Among Muslim Tamils in the Klang Valley

LANGUAGE SHIFT AMONG MUSLIM TAMILS IN THE KLANG VALLEY AZEEZAH JAMEELAH BT. MOHAMED MOHIDEEN DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ENGLISH AS A SECOND LANGUAGE FACULTY OF LANGUAGES AND LINGUISTICS UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA KUALA LUMPUR 2012 UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA ORIGINAL LITERARY WORK DECLARATION Name of Candidate: Azeezah Jameelah Bt. Mohamed Mohideen I/C No.:730807-10-5714 Matric No.: TGB070012 Name of Degree: Master of English as a Second Language Title of Dissertation (“this Work”): Language Shift among Muslim Tamils in the Klang Valley Field of Study: Sociolinguistics I do solemnly and sincerely declare that:- (1) I am the sole writer/author of this Work; (2) This Work is original; (3) Any use of any work in which copyright exists was done by way of fair dealing and for permitted purposes and any excerpt or extract from, or reference to or reproduction of any copyright work has been disclosed expressly and sufficiently and the title of the work and its authorship have been acknowledged in this Work; (4) I do not have any actual knowledge nor do I ought reasonably to know that the making of this work constitutes an infringement of any copyright work; (5) I hereby assign all and every copyright in this Work to the University of Malaya (“UM”), who henceforth shall be the owner of the copyright in this Work and any reproduction or use in any form or by any means whatsoever is prohibited without the written consent of UM having been first had and obtained; (6) I am fully aware that if in the course of this Work, I have infringed any copyright whether intentionally or otherwise, I may be subject to legal action or any other action as may be determined by UM. -

Inherited Vocabulary of Proto-Austronesian in the Banjarese Language

ISSN: 2186-8492, ISSN: 2186-8484 Print Vol. 2 No. 2 May 2013 ASIAN JOURNAL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES & HUMANITIES INHERITED VOCABULARY OF PROTO-AUSTRONESIAN IN THE BANJARESE LANGUAGE Rustam Effendi Faculty of Teacher Training and Education, Lambung Mangkurat University, Banjarmasin, INDONESIA. [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper attempts to present a reflection of the Proto-Austronesian language in the Banjarese language (BL). Used in the South, Central Kalimantan and East Kalimantan, it is was a lingua franca of trade in the past. Almost all Dayak speech communities are have knowledge of it. In addition, it is also spoken in certain regions of Sumatra, including Tembilahan (Riau) and Sabak Bernam (Malaysia). As a language covering wide area of users, it has many dialects and sub-dialects. Linguists still have different opinions in terms of the BL dialect. Hapip, Suryadikara and Durasid state that BL consists of two dialects. They are the Hulu or the upper- stream dialect and the Kuala or the down-stream dialect. Meanwhile, Kawi claims that there are three Banjarese dialects namely the Hulu Dialect, Kuala dialect, and Bukit or the mountain-range dialect. BL belongs to the family of the Austronesian language. The question is: How are the elements of the Proto-Austronesian (PA) language reflected in Banjarese? In relation to the question, this research is done to describe the reflection of the PA in BL using comparison method and was done by arranging a set of characteristics of the Banjarese vocabulary that correspond the PA etimon. The research result shows that: (a) generally the PA etimony are represented unimpairedly in the BL, (b) the PA’s phonemes are inherited in the BL without any changes, (c) the reflection forms of some words shows some changes; however these changes seem to be sporadic; (d) the phonetic changes tend to refer to the similarities of the articulatory circumference; and (e) not all of the PA etimony is reflected in the BL.