Global Issues and Local Language Literacy Practices in Two Rural Communities of Mexico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6 X 10.5 Long Title.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-51840-6 - An Introduction to Classical Nahuatl Michel Launey Excerpt More information Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī PART Ī Ī ONE Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-51840-6 - An Introduction to Classical Nahuatl Michel Launey Excerpt More information PRELIMINARY LESSON Phonetics and Writing S ince the time of the conquest, Nahuatl has been written by means of theLatinalphabet.Thereis,therefore,alongtraditiontowhichitis preferable to conform for the most part. Nonetheless, for the following reasons, somewordsinthisbookarewritteninanorthographythatdiffersfromthe traditional one. ̈ Theorthographyis,ofcourse,“hispanicized.”Torepresentthephoneticele- ments of Nahuatl, the letters or combinations of letters that represent identical or similar sounds in Spanish are used. Hence, there is no problem with the sounds that exist in both languages, not to mention those that are lacking in Nahuatl (b, d, g, r etc.). On the other hand, those that exist in Nahuatl but not inSpanisharefoundinalternatespellings,orareevenaltogetherignored.In particular, this is the case with vowel length and (even worse) with the glottal stop (see Table 1.1), which are systematically marked only by two grammar- ians, Horacio Carochi and Aldama y Guevara, and in a text named Bancroft Dialogues.1 ̈ This defective character is heightened by a certain fluctuation because the orthography of Nahuatl has never really been fixed. Hence, certain texts represent the vowel /i/ indifferently with i or j, others always represent it with i but extend this spelling to consonantal /y/, that is, to a differ- ent phoneme. -

Saltillo Street Names Index: Autumn Gleen Dr

M R - 6 - E R R - 5 - E C c 1 2 3 D 4 5 6 7 U C S D A T R . E R D L 6 . 8 E 3 Y SNER ST. RD 2446 MES SALTILLO STREET NAMES INDEX: AUTUMN GLEEN DR. E3 OLD HWY. 51 E3 A BAUHAUS DR. E3 OLD NATCHEZ TRACE TRAIL G3 BENT GRASS CIR. H2 OLD SALTILLO RD. E4, F4, F5, G5, H4, H5 A BERCH TREE DR. F4 OLD SOUTH PLANTATION DR. E2 R D BIG HARPE TRAIL G2 OLIVIA CV. D4 BIRMINGHAM RIDGE RD. F1, F2, G3 7 PARKRIDGE DR, F4 8 3 BOLIVAR CIR. G3 PATTERSON CIR. E5 . D BOSTIC AVE. E4 PECAN DR. D5 R BRIDLE CV. E3 PETE AVE. F3 D U BRISCOE ST. E4 PEYTON LN. D4 H BROCK DR. F3 33 35 35 35 PINECREST ST. E4 ST 32 32 33 TOWERY . CARTWRIGHT AVE. E4 PINEHURST AVE. E4 31 36 31 R 4 3 D 3 2 CHAMPIONS CV. H2 PINEWOOD ST. E4 5 6 5 4 CHERRY HILL DR. C4 POPULARWOOD LN. F4 1 6 9 5 CHESTNUT LN. C4 PRINSTON DR. E3 1 CHICKASAW CIR. G3 PULLTIGHT RD. B4, C4 CHICKASAW TRAIL G3 PYLE DR. E4 CHRISTY WAY C4 QUAIL CREEK RD. E3 CO 653-B H2, H3 RAILROAD AVE. E5 CO 653-D G3 RD 189 F3 CO 2012 E2, E3 RD 251 D2 3 CO 2012 F3 8 RD 521 C1, E2 7 CO 2720 A1 RD 599 C1, C2, D2 D R CO 2720 B1 RD 647 H3 COBBS CV. -

Fieldwork and Linguistic Analysis in Indigenous Languages of the Americas

Fieldwork and Linguistic Analysis in Indigenous Languages of the Americas edited by Andrea L. Berez, Jean Mulder, and Daisy Rosenblum Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 2 Published as a sPecial Publication of language documentation & conservation language documentation & conservation Department of Linguistics, UHM Moore Hall 569 1890 East-West Road Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96822 USA http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc university of hawai‘i Press 2840 Kolowalu Street Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96822-1888 USA © All texts and images are copyright to the respective authors. 2010 All chapters are licensed under Creative Commons Licenses Cover design by Cameron Chrichton Cover photograph of salmon drying racks near Lime Village, Alaska, by Andrea L. Berez Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication data ISBN 978-0-8248-3530-9 http://hdl.handle.net/10125/4463 Contents Foreword iii Marianne Mithun Contributors v Acknowledgments viii 1. Introduction: The Boasian tradition and contemporary practice 1 in linguistic fieldwork in the Americas Daisy Rosenblum and Andrea L. Berez 2. Sociopragmatic influences on the development and use of the 9 discourse marker vet in Ixil Maya Jule Gómez de García, Melissa Axelrod, and María Luz García 3. Classifying clitics in Sm’algyax: 33 Approaching theory from the field Jean Mulder and Holly Sellers 4. Noun class and number in Kiowa-Tanoan: Comparative-historical 57 research and respecting speakers’ rights in fieldwork Logan Sutton 5. The story of *o in the Cariban family 91 Spike Gildea, B.J. Hoff, and Sérgio Meira 6. Multiple functions, multiple techniques: 125 The role of methodology in a study of Zapotec determiners Donna Fenton 7. -

Toward a Comprehensive Model For

Toward a Comprehensive Model for Nahuatl Language Research and Revitalization JUSTYNA OLKO,a JOHN SULLIVANa, b, c University of Warsaw;a Instituto de Docencia e Investigación Etnológica de Zacatecas;b Universidad Autonóma de Zacatecasc 1 Introduction Nahuatl, a Uto-Aztecan language, enjoyed great political and cultural importance in the pre-Hispanic and colonial world over a long stretch of time and has survived to the present day.1 With an estimated 1.376 million speakers currently inhabiting several regions of Mexico,2 it would not seem to be in danger of extinction, but in fact it is. Formerly the language of the Aztec empire and a lingua franca across Mesoamerica, after the Spanish conquest Nahuatl thrived in the new colonial contexts and was widely used for administrative and religious purposes across New Spain, including areas where other native languages prevailed. Although the colonial language policy and prolonged Hispanicization are often blamed today as the main cause of language shift and the gradual displacement of Nahuatl, legal steps reinforced its importance in Spanish Mesoamerica; these include the decision by the king Philip II in 1570 to make Nahuatl the linguistic medium for religious conversion and for the training of ecclesiastics working with the native people in different regions. Members of the nobility belonging to other ethnic groups, as well as numerous non-elite figures of different backgrounds, including Spaniards, and especially friars and priests, used spoken and written Nahuatl to facilitate communication in different aspects of colonial life and religious instruction (Yannanakis 2012:669-670; Nesvig 2012:739-758; Schwaller 2012:678-687). -

Otomi and Mazahua

Language and Culture Archives Bartholomew Collection of Unpublished Materials SIL International - Mexico Branch © SIL International NOTICE This document is part of the archive of unpublished language data created by members of the Mexico Branch of SIL International. While it does not meet SIL standards for publication, it is shared “as is” under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc- sa/4.0/) to make the content available to the language community and to researchers. SIL International claims copyright to the analysis and presentation of the data contained in this document, but not to the authorship of the original vernacular language content. AVISO Este documento forma parte del archivo de datos lingüísticos inéditos creados por miembros de la filial de SIL International en México. Aunque no cumple con las normas de publicación de SIL, se presenta aquí tal cual de acuerdo con la licencia "Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-CompartirIgual" (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc- sa/4.0/) para que esté accesible a la comunidad y a los investigadores. Los derechos reservados por SIL International abarcan el análisis y la presentación de los datos incluidos en este documento, pero no abarcan los derechos de autor del contenido original en la lengua indígena. THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO THE RECONSTRUCTION OF OTOPAMEAN (MEXICO) A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT -

A Critique of the Separation Base Method for Genealogical Subgrouping, with Data from Mixe-Zoquean*

Journal of Quantitative Linguistics 2006, Volume 13, Numbers 2 – 3, pp. 225 – 264 DOI: 10.1080/09296170600850759 A Critique of the Separation Base Method for Genealogical Subgrouping, with Data from Mixe-Zoquean* Michael Cysouw, Søren Wichmann and David Kamholz Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig ABSTRACT Holm (2000) proposes the ‘‘separation base’’ method for determining subgroup relationships in a language family. The method is claimed to be superior to most approaches to lexicostatistics because the latter falls victim to the ‘‘proportionality trap’’, that is, the assumption that similarity is proportional to closeness of relationship. The principles underlying Holm’s method are innovative and not obviously incorrect. However, his only demonstration of the method is with Indo-European. This makes it difficult to interpret the results, because higher-order Indo-European subgrouping remains controversial. In order to have some basis for verification, we have tested the method on Mixe-Zoquean, a well-studied family of Mesoamerica whose subgrouping has been established by two scholars working independently and using the traditional comparative method. The results of our application of Holm’s method are significantly different from the currently accepted family tree of Mixe-Zoquean. We identify two basic sources of problems that arise when Holm’s approach is applied to our data. The first is reliance on an etymological dictionary of the proto-language in question, which creates problems of circularity that cannot be overcome. The second is that the method is sensitive to the amount of documentation available for the daughter languages, which has a distorting effect on the computed relationships. -

A Grammar of Umbeyajts As Spoken by the Ikojts People of San Dionisio Del Mar, Oaxaca, Mexico

ResearchOnline@JCU This file is part of the following reference: Salminen, Mikko Benjamin (2016) A grammar of Umbeyajts as spoken by the Ikojts people of San Dionisio del Mar, Oaxaca, Mexico. PhD thesis, James Cook University. Access to this file is available from: http://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/50066/ The author has certified to JCU that they have made a reasonable effort to gain permission and acknowledge the owner of any third party copyright material included in this document. If you believe that this is not the case, please contact [email protected] and quote http://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/50066/ A Grammar of Umbeyajts as spoken by the Ikojts people of San Dionisio del Mar, Oaxaca, Mexico Mikko Benjamin Salminen, MA A thesis submitted to James Cook University, Cairns In fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Language and Culture Research Centre, Cairns Institute College of Arts, Society and Education - James Cook University October 2016 Copyright Care has been taken to avoid the infringement of anyone’s copyrights and to ensure the appropriate attributions of all reproduced materials in this work. Any copyright owner who believes their rights might have been infringed upon are kindly requested to contact the author by e-mail at [email protected]. The research presented and reported in this thesis was conducted in accordance with the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research, 2007. The proposed research study received human ethics approval from the JCU Human Research Ethics Committee Approval Number H4268. -

Active with AAC

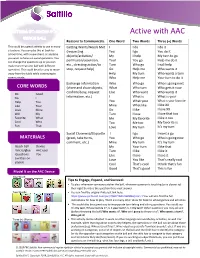

Active with AAC Reasons to Communicate One Word Two Words Three (+) Words This could be a great activity to use in many Getting Wants/Needs Met I I do I do it situations. You can play this at back-to- (requesting You I go You do it school time, with a new client, or anytime objects/activities/ My I help My turn to go you want to focus on social questions. You can change the questions up or you can permission/attention, Your You go Help me do it make more than one ball with different etc., directing action/to Turn Who go I will help stop, request help) Go Help me Who wants it questions. This could be a fun way to move away from the table while continuing to Help My turn Who wants a turn communicate. Who Help me Your turn to do it Exchange Information Who Who go Who is going next CORE WORDS (share and show objects, What Who turn Who gets it now confirm/deny, request Like Who want Who wants it Do Good Go I information, etc.) I What is What is your Help You You What your What is your favorite Like Your Mine What like I like XX Love Mine Go I like I love XX Will My Turn I love I love that too Favorite What Me My favorite I like it too Cool Who Too Me too My favorite is Fun That Love My turn It’s my turn Social Closeness/Etiquette I I go I want a go MATERIALS (greet, take turns, You Who go Who is going now comment, etc.) Mine My turn It’s my turn Beach ball Device My Your turn I like that Velcro/glue AAC user Turn I like I like it Questions You Like I love I love it (written on Love You like That’s really cool paper) Cool That’s cool I think that’s fun Good That’s good This is fun Model It on the AAC Device One Word: Tips to Engage, Expand, and Succeed: • To play: whenever someone catches the ball, whatever question is touching (or is closest to) their right thumb is the question they must answer. -

Bftrkeley and LOS ANGELES 1945 SIERRA POPOLUCA FOLKLORE and BELIEFS

SIERRA POPOLUCA FOLKLORE AND BELIEFS BY GEORGE M. FOSTER UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PUBLICATIONS IN AMERICAN ARCHAEOLOGY AND ETHNOLOGY Volume 42, No. 2, pp. 177-250 UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS BFtRKELEY AND LOS ANGELES 1945 SIERRA POPOLUCA FOLKLORE AND BELIEFS BY GEORGE M. FOSTER UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS BERKELEY AND LOS ANGELES 1945 UNIvERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PUJBLICATIONS IN AMERICAN ARCHAEOLOGY AND ETHNOLOGY EDITORS (Los ANGELES): RALTPH L. BEALS, FRANEKLN FEARING, HARRY HOIJER Volume 42, No. 2, pp. 177-250 Submitted by editors September 30, 1943 Issued January 19, 1945 Price, 75 cents UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS BERKELEY AND Los ANGELES CALIFORNIA CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON, ENGLAND PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERIOA CONTENTS PAGE I. INTTRODUCTION ........................ .......................... 177 II. STORIIES 1. The Origin of Maize .................................................. 191 2. The Origin of Maize (Second Version) ....................... 196 3. Two Men Meet a Rayo .................................................. 196 4. Story of the Armadillo .................................................. 198 5. Why the Alligator Has No Tongue ......................... 199 6. How the Turkey Lost His Means of Defense . .................... 199 7. Origin of the Partridge .................................................. 199 8. Why Copal Is Burned for the Chanekos ....................... 200 9. An Encounter with Chanekos ............................................. 201 10. The Chaneko, The Man, His Mistress, -

Studie V Příruční Studovně Separátů

Studie v příručce separátů LING (č. 419a) Sestavil: Jan Křivan Afrika (africké jazyky) • Kamwe (Higi) Mohrlang, Roger (1971). VECTORS, PROSODIES, AND HIGI VOWELS. Journal of African Languages . Téma: fonetika. Více informací. • Ejagham (Etung) Edmondson, T. & Bendor-Samuel, J.T. (1966). TONE PATTERNS OF ETUNG. Journal of African Languages . Téma: fonetika. Více informací. • Igede (Igede) Bergman, Richard (1971). VOWEL SANDHI AND WORD DIVISION IN IGEDE. J.W.A.L.. Téma: fonologie. Více informací. • Hun-Saare (Duka) Bendor-Samuel, John & Cressman, Esther & Skitch, Donna (1971). THE NOMINAL PHRASE IN DUKA. J.W.A.L.. Téma: syntax. Více informací. • Nuclear Igbo (Izi) Bendor-Samuel, J.T. (1968). VERB CLUSTERS IN IZI. J.W.A.L.. Téma: syntax. Více informací. • Nuclear Igbo (Izi) Bendor-Samuel, J.T. & Meier, Inge (1967). SOME CONTRASTING FEATURES OF THE IZI VERBAL SYSTEM. Institute of linguistics. Téma: syntax. Více informací. • Legbo (Agbo) Bendor-Samuel J.T. & Spreda, K.W. (1969). FORTIS ARTICULATION: A FEATURE OF THE PRESENT CONTINUOUS VERB IN AGBO. Linguistics An International Review. Téma: fonetika. Více informací. • Lokaa (Yakur) Bendor-Samuel, J.T. (1969). YAKUR SYLLABLE PATTERNS. Word. Téma: fonologie. Více informací. • Mossi – Dagbani – Gourmanchema (Afrikanische Sprachen) Westermann, Diedrich (1947). PLURALBILDUNG UND NOMINALKLASSEN IN EINIGEN AFRIKANISCHEN SPRACHEN. Abhandlungen der deutschen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin. Téma: srovnání. Více informací. • Dagbani (Dagbani) Wilson, W.A.A. & Bendor-Samuel J.T. (1969). THE PHONOLOGY OF THE NOMINAL IN DAGBANI. Linguistics An International Review. Téma: fonologie. Více informací. • Bimoba – Moba (Bimoba) Bendor-Samuel, John T. (1965). PROBLEMS IN THE ANALYSIS OF SENTENCES AND CLAUSES IN BIMOBA. Word. Téma: syntax. Více informací. -

A Linguistic Look at the Olmecs Author(S): Lyle Campbell and Terrence Kaufman Source: American Antiquity, Vol

Society for American Archaeology A Linguistic Look at the Olmecs Author(s): Lyle Campbell and Terrence Kaufman Source: American Antiquity, Vol. 41, No. 1 (Jan., 1976), pp. 80-89 Published by: Society for American Archaeology Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/279044 Accessed: 24/02/2010 18:09 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=sam. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Society for American Archaeology is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Antiquity. http://www.jstor.org 80 AMERICAN ANTIQUITY [Vol. 41, No. 1, 1976] Palomino, Aquiles Smith, Augustus Ledyard, and Alfred V. -

Copyright by Susan Smythe Kung 2007

Copyright by Susan Smythe Kung 2007 The Dissertation Committee for Susan Smythe Kung Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: A Descriptive Grammar of Huehuetla Tepehua Committee: Nora C. England, Supervisor Carlota S. Smith Megan Crowhurst Anthony C. Woodbury Paulette Levy James K. Watters A Descriptive Grammar of Huehuetla Tepehua by Susan Smythe Kung, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2007 Dedication For the Tepehua people of Huehuetla, Hidalgo, Mexico, and especially for Nicolás. If it were not for their friendship and help, I never would have begun this dissertation. If it were not for their encouragement of me, as well as their commitment to my project, I never would have finished it. Acknowledgements My first and largest debt of gratitude goes to all of the speakers of Huehuetla Tepehua who contributed in some way to this grammar. Without them, this volume would not exist. I want to thank the Vigueras family, in particular, for taking me into their home and making me a part of their family: don Nicolás, his wife doña Fidela, their children Nico, Tonio, Mari, Carmelo, Martín, Lupe, and Laurencio, and their daughter-in-law Isela. Not only do I have a home here in the U.S., but I also have a home in Huehuetla with them. There was also the extended family, who lived in the same courtyard area and who also took me in and gave me free access to their homes and their lives: don Nicolás’ mother doña Angela, his two brothers don Laurencio and don Miguel, their wives doña Fidela and doña Juana, and all of their children.