The Life and Letters of Margaret Junkin Preston

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer 2017 Czech Film Center

Summer 2017 Czech Film Center The Czech Film Center (CFC) was established in 2002 to represent, market and promote Czech cinema and film industry and to increase the awareness of Czech film worldwide. As a national partner of international film festivals and co-production platforms, CFC takes active part in selection and presentation of Czech films and projects abroad. Linking Czech cinema with international film industry, Czech Film Center works with a worldwide network of international partners to profile the innovation, diversity and creativity of Czech films, and looks for opportunities for creative exchange between Czech filmmakers and their international counterparts. CFC provides tailor-made consulting, initiates and co-organizes numerous pitching forums and workshops, and prepares specialized publications. As of February 2017, the Czech Film Center operates as a division of the State Cinematography Fund Czech Republic. Markéta Šantrochová Barbora Ligasová Martin Černý Head of Czech Film Center Festival Relations-Feature Films Festival Relations-Documentary e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] & Short Films tel.:+420 724 329 948 tel.: +420 778 487 863 e-mail: [email protected] tel.: +420 778 487 864 Rita Henzelyová Hedvika Petrželková Project Manager Editor & External Communication e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] tel.: +420 724 329 949 tel.: +420 770 127 726 Bohdan Sláma / In his new film, Ice Mother, Bohdan Sláma, revisits the theme of family, Barefoot / this time with a little more humor Oscar-winning and hope. director Jan Svěrák (Kolya) is finishing up his latest feature, 4 titled Barefoot. 10 Czech Film Springboard / 14 The second edition of the industry initiative organized by Czech Film Center and Finále Plzeň. -

Descendants of Joseph Junkin and Elizabeth Wallace Junkin

Descendants of Joseph Junkin and Elizabeth Wallace Junkin Generation 1 1. JOSEPH 1JUNKIN was born about 1715 in Monahan, Antrim, Ulster, Irelamd. He died on 01 Apr 1777 in Kingston, Cumberland Co, PA, USA (buried Silver Spring Burial Ground : may NOT be the same as the Silver Springs Presbyterian Church graveyard. In fact I think it was a family plot on the family farm.). He married Elizabeth Wallace, daughter of John Wallace and Martha Hays, in 1743 in Peach Bottom, York County, Pennsylvania. She was born between 1722-1724 in Tyrone, Tyrone, Ireland. She died on 10 Apr 1796 in Kingston, Cumberland, Pennsylvania, United States (buried Silver Spring Burial Ground : may NOT be the same as the Silver Springs Presbyterian Church graveyard. In fact I think it was a family plot on the family farm.). Joseph Junkin and Elizabeth Wallace had the following children: 2. i. WILLIAM 2JUNKIN was born in 1744 in East Pennsboro Twp. Cumberland County, Pennsylvania. He died in 1825 in Junkin Mills, Wayne Township, Mifflin County, Pennsylvania. He married Jane Galloway, daughter of George Galloway and Rebecca Junkin, in 1769. She was born on 08 Jan 1745. She died in 1786 in Junkin Mills, Wayne Township, Mifflin County, Pennsylvania. ii. MARY POLLY JUNKIN was born in 1747 in East Pennsboro Twp. Cumberland County, Pennsylvania. She died in 1825 in Culbertson's Run, Mifflin County, Pennsylvania. She married John Culbertson about 1767. He was born about 1747 in Culbertson's Run, Mifflin County, Pennsylvania. He died on 08 Jul 1811. 3. iii. JOSEPH JUNKIN II was born on 22 Jan 1750 in East Pennsboro Twp. -

Earl A. Pope Papers, Skillman Library 1828-2003 Lafayette College

EARL A. POPE PAPERS, SKILLMAN LIBRARY 1828-2003 LAFAYETTE COLLEGE BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Born in Tulca, Romania, on August 18, 1920, Earl A. Pope immigrated to the United States with his parents, Moses and Lena Pope, in 1923 (they celebrated Earl’s third birthday aboard the trans-Atlantic ship). After growing up in Akron, Ohio, where he graduated from Garfield High School in 1939, he attended Wheaton College, Wheaton, Illinois, earning an A.B. in Religion and an M.A. in Theology. He enrolled in Yale University Divinity School, where he was awarded a M.Div. degree in the History of Christianity. In 1948, while at Yale, he met Miriam (Mim) Nilsen, in Cromwell, Connecticut; they were married on September 9, 1950. For the next decade, The Rev. Earl A. Pope, ordained in the Evangelical Covenant Church of America, was the minister of churches in Floral Park, NY (1950-53), Cranston, RI (1954-57), and Rumford, RI (1957-60). While serving at the Rumford church, he also served for two years as a teaching fellow at Brown University, where he earned a Ph.D. in Religious Studies and American History. In 1960, Pope joined the Faculty of Lafayette College, where he taught in the Department of Religion for the next 30 years. While rising through the ranks of assistant, associate, and full professor and eventually being named (in 1988) the Helen H. P. Manson Professor of Bible, he also served in several administrative positions, including Head of the Religion Department (1977-85) and Dean of Studies (1970-72). Popular and effective as a teacher, Pope taught courses in scripture, world religions, religious history, ecumenism, and interfaith relations. -

Clique Steamrollers All Class Elections with Little Trouble

Dr. George Junkin, founder of Miami university and former pres • TbJ.s year marks the tenth an Ident of Lafayette College, Is bur niversary of the reestablishment ted in the Lexington cemetery. l or the Lee SChool ot Journalism. By the Studenta, For the Studenta VOL. XL WASHINGTON AND LEE UNIVERSITY, TUESDAY, OCfOBER 6, 1 936 NUMBER 5 ==;===~========~====~_;~ Dr. Helderman Applications for Degrees Faculty Passes Graham Explains Rules Due Before October 15 Clique Steamrollers To Address IRC Registrar E. S. Mattingly today On Seven For For Opening Dance Set warned all candidates tor degrees Thursday Night of any kind to be sure to tile their Rhodes Award All Class Elections formal applications before Octo Regulations governing the sale In the flaure will be Issued by the ber 15. He said that this must be ucriais in Spain" Chosen of tickets at the opentna dance ticket sellers at that end of the done by every student who ex set were announced last night by a:vmnaalum. Six Seniors, One Graduate As Subject for Club's pects to graduate this coming With Little Trouble Bob Graham, president of the Co- The south entrance of the IYDl· June. Reconunended For tilllon Club. naslum <the end neareat the dor- Initial Meeting B~ for applications may be ---------------------------· Payment of SOphomore dues mitories> wlll be reeerved exclu Scholarships obtained at the Registrar's office tbls year wlll entitle members of slvely tor Juniors. seniors, and Kemp Signed to Play Russ Doane and Jim Ruth and must be handed in to hlm, ac ROUND-TABLE TALK the class merely to participate ln law students who have paid sopb Appointed for Vacancies cording to a notice P<>8ted on all M. -

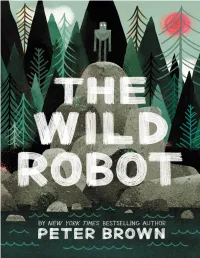

The Wild Robot.Pdf

Begin Reading Table of Contents Copyright Page In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher is unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights. To the robots of the future CHAPTER 1 THE OCEAN Our story begins on the ocean, with wind and rain and thunder and lightning and waves. A hurricane roared and raged through the night. And in the middle of the chaos, a cargo ship was sinking down down down to the ocean floor. The ship left hundreds of crates floating on the surface. But as the hurricane thrashed and swirled and knocked them around, the crates also began sinking into the depths. One after another, they were swallowed up by the waves, until only five crates remained. By morning the hurricane was gone. There were no clouds, no ships, no land in sight. There was only calm water and clear skies and those five crates lazily bobbing along an ocean current. Days passed. And then a smudge of green appeared on the horizon. As the crates drifted closer, the soft green shapes slowly sharpened into the hard edges of a wild, rocky island. The first crate rode to shore on a tumbling, rumbling wave and then crashed against the rocks with such force that the whole thing burst apart. -

Walpole Public Library DVD List A

Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] Last updated: 9/17/2021 INDEX Note: List does not reflect items lost or removed from collection A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Nonfiction A A A place in the sun AAL Aaltra AAR Aardvark The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.1 vol.1 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.2 vol.2 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.3 vol.3 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.4 vol.4 ABE Aberdeen ABO About a boy ABO About Elly ABO About Schmidt ABO About time ABO Above the rim ABR Abraham Lincoln vampire hunter ABS Absolutely anything ABS Absolutely fabulous : the movie ACC Acceptable risk ACC Accepted ACC Accountant, The ACC SER. Accused : series 1 & 2 1 & 2 ACE Ace in the hole ACE Ace Ventura pet detective ACR Across the universe ACT Act of valor ACT Acts of vengeance ADA Adam's apples ADA Adams chronicles, The ADA Adam ADA Adam’s Rib ADA Adaptation ADA Ad Astra ADJ Adjustment Bureau, The *does not reflect missing materials or those being mended Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] ADM Admission ADO Adopt a highway ADR Adrift ADU Adult world ADV Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ smarter brother, The ADV The adventures of Baron Munchausen ADV Adverse AEO Aeon Flux AFF SEAS.1 Affair, The : season 1 AFF SEAS.2 Affair, The : season 2 AFF SEAS.3 Affair, The : season 3 AFF SEAS.4 Affair, The : season 4 AFF SEAS.5 Affair, -

![[Pennsylvania County Histories]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5258/pennsylvania-county-histories-1315258.webp)

[Pennsylvania County Histories]

■ ' - .. 1.ri^^fSgW'iaBgSgajSa .. --- v i- ’ -***’... • '■ ± i . ; :.. - ....•* 1 ' • *’ .,,■•••■ - . ''"’•'"r.'rn'r .■ ' .. •' • * 1* n»r*‘V‘ ■ ■ •••■ *r:• • - •• • • .. f • ..^*»** ••*''*■*'*■'* ^,.^*«»*♦» ,.r„H 2;" •*»«.'* ;. I, . 1. .••I*'-*"** ' .... , .• •> -• * * • ..••••* . ... •• ’ vS -ft 17 V-.? f 3 <r<s> // \J, GS Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2018 with funding from This project is made possible by a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services as administered by the Pennsylvania Department of Education through the Office of Commonwealth Libraries https://archive.org/details/pennsylvaniacoun63unse SNMX. A Page . B Page B Page B C D D iitsim • - S Page S Pase S T uv w w w XYZ A GOOD M, I with chain, theodolite and compass. He spent his days in earning bread for his Sketch of the Career sons, family, and his evenings in preparing for AY ho “Kockeil East ra<Ue and future usefulness. His energies were too Watched Over Her Infant Footsteps With vigorous to be confined in a shoemaker’s Paternal Solicitude”—A Proposition to shop. He was ambitious ot a wider and Erect a Handsome Monument in the higher field of labor. His shop was his Circle to His Memory. * college and laboratory, and he was professor There is in the minds of many in Easton and student. While his genial wife sang the feeling that the recollections of William lullabies to her babe, Parsons was quietly Parsons shall be perpetuated by a suitable solving problems in surveying aud master¬ monument erected to bis memory. Cir¬ ing the use of logarithmic tables. It is not cumstances of recent occurrence have strange if he had some idea of future fame. -

Addresses on the Occasion of the Inauguration of Ethelbert Ducley

28775 A 58548 4 DUPL 1891 Narfield Christian Education STORAGE 1 . 2 a 5 Univ . of Mich . GENERAL LIBRARY of the UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN - PRESENTED BY Pres J . B Angell from Pres . Angell . May , to HRISTIAN EDUCATION . AN INAUGURAL ADDRESS BY ETHELBERT D . WARFIELD , LL . D . , President of Lafayette College . Lafayette College , OCTOBER 20th , 1891 . 39768 LAFAYETTE COLLEGE PUBLICATIONS . ANNUAL CATALOGUE . See third page of cover . THE MEN OF LAFAYETTE . S . J . Coffin , Ph . D . Graduate Catalogue . 1890 . $ 2 . 50 . THE LAFAYETTE . A College Periodical , pub lished by the Students semi -monthly during College Year . $ 1 . 50 per annum . THE MELANGE . A College Annual published by the Junior Class . Circa 200 pp . 8vo . 75 cents . LAFAYETTE COLLEGE . A Descriptive Pam phlet . 4 cts . Also , Examination Papers , occasional Ad dresses , etc . , which may be had by enclos ing stamps for postage to the SECRETARY , or THE REGISTRAR , Lafayette College , Easton , Pa . LAFAYETTE COLLEGE . 39768 ADDRESSES ON THE OCCASION OF THE INAUGURATION OF Ethelbert Dudley Warfield , LL . D . , AS PRESIDENT OF LAFAYETTE COLLEGE . EASTON , PENNSYLVANIA . : - PUBLISHED BY THE COLLEGE . 1891 . THE WEST PRINTING HOUSE EASTON , PENNA . PREFATORY NOTE . ETHELBERT DUDLEY WARFIELD , LL . D . , at that time President of Miami University , was elected to the presi dency of Lafayette College by the unanimous vote of the Board of Trustees , on March 17 , 1891 . Having signi fied his acceptance of the position thus tendered him , the first of September was appointed as the day on which he should assume the duties of the office . It being neces sary that the Synod of Pennsylvania should approve the appointment the formal act of induction was delayed until the Synod should have an opportunity to act at its annual meeting in October . -

The Anti-Slavery Movement in the Presbyterian Church, 1835-1861

This dissertation has been 62-778 microfilmed exactly as received HOWARD, Victor B., 1915- THE ANTI-SLAVERY MOVEMENT IN THE PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH, 1835-1861. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1961 History, modem University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE ANTI-SLAVERY MOVEMENT IN THE PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH, 1835-1861 DISSERTATION Presented In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University 9r Victor B, Howard, A. B., A. M. ****** The Ohio State University 1961 Approved by Adviser Department of History CONTENTS Chapter Page I The Division of 1837. .................. 1 II The Church Crystallizes Its Position On Slavery............. 89 III The Impact of the Fugitive Slave Law Upon the Church ........................... 157 IV Political Controversy and Division. .... 181 V The Presbyterian Church and the American Home Missionary Society........... 222 VI Anti-Slavery Literature and the Tract S o c i e t y ................................... 252 VII Foreign Missions and Slavery Problems . 265 VIII A Northwestern Seminary ................. 290 IX Crisis of 1 8 6 1 . ................. 309 Bibliography............................... 342 Autobiography..................................... 378 il CHAPTER I THE DIVISION OF 1837 In 1824 in central western New York, Charles G. Finney began a career in ministry that was to have far- reaching implications for the religious as well as the civil life of the people of the United States. In July of that year he was ordained by the Presbytery of St. Lawrence, and assigned as a missionary to the little towns of Evans Mills and Antwerp in Jefferson County, New York. Under the vivid preaching of this ex-lawyer a wave of revivalism began to sweep through the whole region.^ Following the revival of 1824-27, Finney carried the religious awakening into Philadelphia, New York City, and Rochester, New York. -

British Film Institute Report & Financial Statements 2006

British Film Institute Report & Financial Statements 2006 BECAUSE FILMS INSPIRE... WONDER There’s more to discover about film and television British Film Institute through the BFI. Our world-renowned archive, cinemas, festivals, films, publications and learning Report & Financial resources are here to inspire you. Statements 2006 Contents The mission about the BFI 3 Great expectations Governors’ report 5 Out of the past Archive strategy 7 Walkabout Cultural programme 9 Modern times Director’s report 17 The commitments key aims for 2005/06 19 Performance Financial report 23 Guys and dolls how the BFI is governed 29 Last orders Auditors’ report 37 The full monty appendices 57 The mission ABOUT THE BFI The BFI (British Film Institute) was established in 1933 to promote greater understanding, appreciation and access to fi lm and television culture in Britain. In 1983 The Institute was incorporated by Royal Charter, a copy of which is available on request. Our mission is ‘to champion moving image culture in all its richness and diversity, across the UK, for the benefi t of as wide an audience as possible, to create and encourage debate.’ SUMMARY OF ROYAL CHARTER OBJECTIVES: > To establish, care for and develop collections refl ecting the moving image history and heritage of the United Kingdom; > To encourage the development of the art of fi lm, television and the moving image throughout the United Kingdom; > To promote the use of fi lm and television culture as a record of contemporary life and manners; > To promote access to and appreciation of the widest possible range of British and world cinema; and > To promote education about fi lm, television and the moving image generally, and their impact on society. -

CRCEES Winter Festival 2008-09 CRCEES Winter Festival 2008-09

CRCEES Winter Festival 2008-09 CRCEES Winter Festival 2008-09 CONTENTS 01 Introduction 04 Visual Arts 09 Winter Festival of Central European Film 27 Music 32 Literary Events 36 Theatre 37 Academic Events 41 Language Learning 01 www.gla.ac.uk/crcees CRCEES Winter Festival 2008-09 The Centre for Russian, Central and East European The season will end with two major Conferences: Studies have great pleasure in hosting a major in February we will examine good practice in the Festival of Arts and Cultures in the Winter season teaching of the languages and cultures we offer of 2008/2009. and the season will conclude with the annual CRCEES Research Forum, to be held in Glasgow The Winter Festival will showcase the enormous in April 2009. breadth of CRCEES’ academic provision in terms of languages and cultures, and will open out an We look forward to welcoming you to this rich extraordinary wealth of resources to the Scottish programme of events. If you would like to know and the UK public more widely. more about the countries covered by this festival and be involved in future activities, please check The season includes major academic conferences our website or contact us for more information. on Hungary and Latvia and a special symposium entitled ‘Inter-cultural Crossings’ where speakers The organisers would like to express their from many European countries will bear witness appreciation to colleagues in the Department of to the powerful ‘crossings’ of other cultures into Central and East European Studies and those their own. in the Slavonic Studies section of the School of Modern Languages and Cultures at the University Throughout the Festival there will be films, of Glasgow as well as to the many colleagues in exhibitions of visual arts, literary readings, musical the partner institutions of CRCEES. -

Alessandro Baricco

Table of Contents Title Page Prologue Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Chapter 13 Chapter 14 Chapter 15 Chapter 16 Chapter 17 Chapter 18 Chapter 19 Chapter 20 Chapter 21 Chapter 22 Chapter 23 Chapter 24 Chapter 25 Chapter 26 Chapter 27 Chapter 28 Chapter 29 Chapter 30 Chapter 31 Chapter 32 Chapter 33 Chapter 34 Chapter 35 Epilogue About the Author Also by Alessandro Baricco Copyright Page Prologue “So, Mr. Klauser, should Mami Jane die?” “Screw them all.” “Is that a yes or a no?” “What do you think?” In October of 1987, CRB—the company that for twenty-two years had published the adventures of the mythical Ballon Mac— decided to take a poll of its readers to determine whether Mami Jane ought to die. Ballon Mac was a blind superhero who worked as a dentist by day and at night battled Evil, using the special powers of his saliva. Mami Jane was his mother. The readers were, in general, very fond of her: she collected Indian scalps and at night she performed as a bassist in a blues band whose other members were black. She was white. The idea of killing her off had come from the sales manager of CRB —a placid man who had a single passion: toy trains. He maintained that at this point Ballon Mac was on a dead-end track and needed new inspiration. The death of his mother—hit by a train as she fled a paranoid switchman— would transform him into a lethal mixture of rage and grief, that is, the exact image of his average reader.