Push DOODLES New Thinking About Roleplaying Volume 1 INTRODUCTION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collaborative Storytelling 2.0: a Framework for Studying Forum-Based Role-Playing Games

COLLABORATIVE STORYTELLING 2.0: A FRAMEWORK FOR STUDYING FORUM-BASED ROLE-PLAYING GAMES Csenge Virág Zalka A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2017 Committee: Kristine Blair, Committee Co-Chair Lisa M. Gruenhagen Graduate Faculty Representative Radhika Gajjala, Committee Co-Chair Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Kristine Blair and Radhika Gajjala, Committee Co-Chairs Forum-based role-playing games are a rich, yet barely researched subset of text- based digital gaming. They are a form of storytelling where narratives are created through acts of play by multiple people in an online space, combining collaboration and improvisation. This dissertation acts as a pilot study for exploring these games in their full complexity at the intersection of play, narrative, and fandom. Building on theories of interactivity, digital storytelling, and fan fiction studies, it highlights forum games’ most unique features, and proves that they are is in no way liminal or secondary to more popular forms of role-playing. The research is based on data drawn from a large sample of forums of various genres. One hundred sites were explored through close textual analysis in order to outline their most common features. The second phase of the project consisted of nine months of participant observation on select forums, in order to gain a better understanding of how their rules and practices influence the emergent narratives. Participants from various sites contributed their own interpretations of forum gaming through a series of ethnographic interviews. This did not only allow agency to the observed communities to voice their thoughts and explain their practices, but also spoke directly to the key research question of why people are drawn to forum gaming. -

International Journal of Role-Playing

International Journal of Role-Playing The aim of The International Journal of Role-Playing is to act as a hybrid knowledge network, and bring together the varied interests in role-playing and the associated knowledge networks, e.g. academic research, the games and creative industries, the arts and the strong role- playing communities. Editorial The Many Faces of Role- The Invisible Rules of Role- Playing Games Playing. The Social The International Journal of Framework of Role-Playing Role-Playing is a response to a By examining a range of role- Process growing need for a place where playing games some common the varied and wonderful fields of features of them emerge. This This paper looks at the process of role-playing research and - results in a definition that is role-playing that takes place in development, covering academia, more successful then previous various games. Role-play is a the industry and the arts, can ones at identifying both what is, social activity, where three exchange knowledge and and what is not, a role-playing elements are always present: An research, form networks and game. imaginary game world, a power communicate. structure and personified player Michael Hitchens characters. Anders Drachen Anders Drachen Editorial Board IJRP Macquirie University Markus Montola Australia University of Tampere Finland 2 3-21 22-36 Roles and Worlds in the Seeking Fulfillment: A Hermeneutical Approach to Hybrid RPG Game of Comparing Role-Play In Role-Playing Analysis Oblivion Table-top Gaming and World of Warcraft This is an article about viewing Single player games are now role-playing games and role- powerful enough to convey the Through ethnographic research playing game theory from a impression of shared worlds with and a survey of World of hermeneutical standpoint. -

SILVER AGE SENTINELS (D20)

Talking Up Our Products With the weekly influx of new roleplaying titles, it’s almost impossible to keep track of every product in every RPG line in the adventure games industry. To help you organize our titles and to aid customers in finding information about their favorite products, we’ve designed a set of point-of-purchase dividers. These hard-plastic cards are much like the category dividers often used in music stores, but they’re specially designed as a marketing tool for hobby stores. Each card features the name of one of our RPG lines printed prominently at the top, and goes on to give basic information on the mechanics and setting of the game, special features that distinguish it from other RPGs, and the most popular and useful supplements available. The dividers promote the sale of backlist items as well as new products, since they help customers identify the titles they need most and remind buyers to keep them in stock. Our dividers can be placed in many ways. These are just a few of the ideas we’ve come up with: •A divider can be placed inside the front cover or behind the newest release in a line if the book is displayed full-face on a tilted backboard or book prop. Since the cards 1 are 11 /2 inches tall, the line’s title will be visible within or in back of the book. When a customer picks the RPG up to page through it, the informational text is uncovered. The card also works as a restocking reminder when the book sells. -

Roll 2D6 to Kill

1 Roll 2d6 to kill Neoliberal design and its affect in traditional and digital role-playing games Ruben Ferdinand Brunings August 15th, 2017 Table of contents 2 Introduction: Why we play 3. Part 1 – The history and neoliberalism of play & table-top role-playing games 4. Rules and fiction: play, interplay, and interstice 5. Heroes at play: Quantification, power fantasies, and individualism 7. From wargame to warrior: The transformation of violence as play 9. Risky play: chance, the entrepreneurial self, and empowerment 13. It’s ‘just’ a game: interactive fiction and the plausible deniability of play 16. Changing the rules, changing the game, changing the player 18. Part 2 – Technics of the digital game: hubristic design and industry reaction 21. Traditional vs. digital: a collaborative imagination and a tangible real 21. Camera, action: The digitalisation of the self and the representation of bodies 23. The silent protagonist: Narrative hubris and affective severing in Drakengard 25. Drakengard 3: The spectacle of violence and player helplessness 29. Conclusion: Games, conventionality, and the affective power of un-reward 32. References 36. Bibliography 38. Introduction: Why we play 3 The approach of violence or taboo in game design is a discussion that has historically been a controversial one. The Columbine shooting caused a moral panic for violent shooter video games1, the 2007 game Mass Effect made FOX News headlines for featuring scenes of partial nudity2, and the FBI kept tabs on Dungeons & Dragons hobbyists for being potential threats after the Unabomber attacks.3 The question ‘Do video games make people violent?’ does not occur within this thesis. -

I Never Took Myself Seriously As a Writer Until I Studied at Macquarie.” LIANE MORIARTY MACQUARIE GRADUATE and BEST-SELLING AUTHOR

2 swf.org.au RESEARCH & ENGAGEMENT 1817 - 2017 luxury property sales and rentals THE UN OF ITE L D A S R T E A T N E E S G O E F T A A M L E U R S I N C O A ●C ● SYDNEY THE LIFTED BROW Welcome 3 SWF 2017 swf.org.au A Message from the Artistic Director Contents eading can be a mixed blessing. For In a special event, writer and photographer 4-15 anyone who has had the misfortune Bill Hayes talks to Slate’s Stephen Metcalf about City & Walsh Bay to glance at the headlines recently, Insomniac City: New York, Oliver, and Me, an the last few months have felt like a intimate love letter to New York and his late Guest Curators 4 long fever dream, for reasons that partner, beloved writer and neurologist extend far beyond the outcome of the Oliver Sacks. R Bernadette Brennan has delved into 7 US Presidential election or Brexit. Nights at Walsh Bay More than 20 million refugees are on the move the career of one of Australia’s most adept and another 40 million people are displaced in and admired authors, Helen Garner, with Thinking Globally 11 their own countries, in the largest worldwide A Writing Life. An all-star cast of Garner humanitarian crisis since 1945. admirers – Annabel Crabb, Benjamin Law Scientists announced that the Earth reached and Fiona McFarlane – will join Bernadette City & Walsh Bay its highest temperatures in 2016 – for the third in conversation with Rebecca Giggs about year in a row. -

The Rise of Twitter Fiction…………………………………………………………1

Twitter Fiction: A Shift in Author Function Hilary Hyman Twitter fiction, an example of twenty-first century digital narrative, allows authors to experiment with literary form, production, and dissemination as they engage readers through a communal network. Twitter offers creative space for both professionals and amateurs to publish fiction digitally, enabling greater collaboration among authors and readers. Examining Jennifer Egan’s “Black Box” and selected Twitter stories from Junot Diaz, Teju Cole, and Elliott Holt, this thesis establishes two distinct types of Twitter fiction—one produced for the medium and one produced through it—to consider how Twitter’s present feed and character limit fosters a uniquely interactive reading experience. As the conversational medium calls for present engagement with the text and with the author, Twitter promotes newly elastic relationships between author and reader that renegotiate the former boundaries between professionals and amateurs. This thesis thus considers how works of Twitter fiction transform the traditional author function and pose new questions regarding digital narrative’s modes of existence, circulation, and appropriation. As digital narrative makes its way onto democratic forums, a shifted author function leaves us wondering what it means to be an author in the digital age. Twitter Fiction: A Shift in Author Function Hilary Anne Hyman Twitter Fiction: A Shift in Author Function Hilary Anne Hyman An Undergraduate Honors Thesis Submitted to the Department of English at Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Major April 18, 2016 Thesis Adviser: Vera Kutzinski Date Second Reader: Haerin Shin Date Program Director: Teresa Goddu Date For My Parents Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge Professor Teresa Goddu for shaping me into the writer I have become. -

Intellectual Property and Gender Implications in Online Games

ARTICLES PRETENDING WITHOUT A LICENSE: INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY AND GENDER IMPLICATIONS IN ONLINE GAMES CASEY FIESLER+ I.Introduction............................. .................. 1 II.Pretending and Storytelling in Borrowed Worlds ....... .......... 4 A. Role Playing in the Sand............................ 7 B. Women in the Sandbox ..................... 10 C. Building Virtual Sandcastles............... .......... 13 III.Pretending Without a License ....................... 19 A. Fanwork and Copyright ............ .. ............. 19 B. The Problem with Play........................... 25 C. Paper Doll Princesses and Virtual Castles.................... 26 IV.The Future of Pretending ................................ 31 A. Virtual Paper Dolls .................................... 31 B. Virtual Sandboxes .......................... 32 V.Conclusion .............................................. 33 "It beats playing with regular Barbies."' I. INTRODUCTION According to media accounts, it is only in the past decade or so that video-game designers begun to appreciate the growing female gamer demographic.2 Though the common strategy for targeting these consumers I PhD Candidate, Human-Centered Computing, Georgia Institute of Technology. JD, Vanderbilt University Law School, 2009. An early draft of this article was presented at the 2009 IP/Gender Symposium at American Law School; the author wishes to thank the participants for their valuable input, as well as Professor Steven Hetcher of Vanderbilt Law School. ' A statement by 9-year-old Presleigh, who would rather play with dolls on a website called Cartoon Doll Emporium. Matt Richtel & Brad Stone, Logging On, Playing Dolls, N.Y. TIMES, June 6, 2007, at Cl. 2 E.g., Tina Arons, Gamer Girls: More females flocking to video games, DAILY I 2 BUFFALO INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LAWJOURNAL Vol. IX seems to be to make pink consoles and games about fashion design,' there is a growing recognition of trends that indicate gender differences in gaming style. -

Game Design and Role-Playing Games

This is an Accepted Manuscript of a book chapter published by Routledge in Role- Playing Game Studies: Transmedia Foundations on April 4, 2018, available online: https://www.routledge.com/Role-Playing-Game-Studies-Transmedia-Foundations/Deterding-Zagal/p/book/9781138638907 Please cite as: Björk, Staffan and Zagal, José P. (2018). “Game Design and Role- Playing Games” In Zagal, José P. and Deterding, S. (eds.), Role-Playing Game Studies: Transmedia Foundations. New York: Routledge, 323-336. 18 Game Design and Role-Playing Games Staffan Björk; José Zagal This chapter explores role-playing games (RPGs) from a design perspective. While there are many approaches to acquiring knowledge about RPGs, designers of RPGs often consider the structural elements of a game—its rules and the entities on which the rules act—and how they will interact with each other. One complication of game design, and RPG design specifically, is that “games” involve and describe both the artifacts that makes playing possible – the things we buy in stores – and the gameplay artifacts enable and encourage. While game designers can exert control over the artifact (e.g. a rulebook or software), their ultimate goal is to encourage a certain kind of gameplay. Thus, gameplay, which primarily depends on the player’s behavior, is out of their direct control. Salen and Zimmerman (2004) refer to this as “second-order design” and stress the importance of playtesting to see if the game artifacts generate the desired game activities when used by the intended target group. However, they also stress the importance of game designers having a structural understanding of games as systems so they can anticipate how specific design configurations will work. -

The Platinum Appendix

SHANNON APPELCLINE SHANNON A HISTORY OF THE ROLEPLAYING GAME INDUSTRY THE PLATINUM APPENDIX SHANNON APPELCLINE This supplement to the Designers & Dragons book series was made possible by the incredible support given to us by the backers of the Designers & Dragons Kickstarter campaign. To all our backers, a big thank you from Evil Hat! _Journeyman_ Antoine Pempie Carlos Curt Meyer Donny Van Zandt Gareth Ryder-Han- James Terry John Fiala Keith Zientek malifer Michael Rees Patrick Holloway Robert Andersson Selesias TiresiasBC ^JJ^ Anton Skovorodin Carlos de la Cruz Curtis D Carbonell Dorian rahan James Trimble John Forinash Kelly Brown Manfred Gabriel Michael Robins Patrick Martin Frosz Robert Biddle Selganor Yoster Todd 2002simon01 Antonio Miguel Morales CURTIS RICKER Doug Atkinson Garrett Rooney James Turnbull John GT Kelroy Was Here Manticore2050 Michael Ruff Nielsen Robert Biskin seraphim_72 Todd Agthe 2Die10 Games Martorell Ferriol Carlos Gustavo D. Cardillo Doug Keester Garry Jenkins James Winfield John H. Ken Manu Marron Michael Ryder Patrick McCann Robert Challenger Serge Beaumont Todd Blake 64 Oz. Games Aoren Flores Ríos D. Christopher Doug Kern Gary Buckland James Wood John Hartwell ken Bronson Manuel Pinta Michael Sauer Patrick Menard Robert Conley Sérgio Alves Todd Bogenrief 6mmWar Apocryphal Lore Carlos Ovalle Dawson Dougal Scott Gary Gin Jamie John Heerens Ken Bullock Guerrero Michael Scholl Patrick Mueller-Best Robert Daines Sergio Silvio Todd Cash 7th Dimension Games Aram Glick Carlos Rincon D. Daniel Wagner Douglas Andrew Gary Kacmarcik Jamie MacLaren John Hergenroeder Ken Ditto Manuel Siebert Michael Sean Manley Patrick Murphy Robert Dickerson Herrera Gea Todd Dyck 9thLevel Aram Zucker-Scharff caroline D.J. -

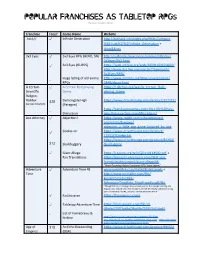

Popular Franchises As Tabletop Rpgs Rev. 7 (Jan

Popular Franchises as Tabletop RPGs Rev. 7 (Jan. 2021) Ctrl+F to find your way around. Use capitalization if nothing is coming up. Franchise Free? Game Name Website .hack// ✓ Infinite Generation http://dothack.info/index.php?title=Category%3 A.hack%2F%2FInfinite_Generation + Odds&Ends A Certain ✓ A Certain Roleplaying https://1d4chan.org/wiki/A_Certain_Role- Scientific Game playing_Game Railgun Ace Attorney ✓ Abjection! https://www.reddit.com/r/AceAttorney/commen ts/8zwgwa/abjection_a_little_rpg_game_inspired _by_ace ✓ Cookie Jar https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/115517/ Cookie-Jar https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/84260/S $12 Skullduggery kulduggery Adventure ✓ Adventure Time 4E www.mediafire.com/?ia9628cdx6zacwb + Time http://www.mediafire.com/file/kmxkml5mzduc9 94/AdventureTimeBeta_PrintFriendly.pdf/file “Though I’m not releasing a new version just for this, people reading this original post should note that hit points should be initially calculated using your constitution SCORE, not your constitution MODIFIER.” FarUniverse https://faruniverse.com/ ✓ https://docs.google.com/file/d/0BwNr37N7Yp6b ✓ Tabletop Adventure Time cDRmMnZSZ0V3a2s/edit - List of homebrews & https://www.reddit.com/r/rpg/comments/81nf9g/any_chance_of_a n_english_adventure_time_rpg/ + https://mutant- history future.fandom.com/wiki/Adventure_Time Age of ✓ Gods and Monsters https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/150889/ Mythology (Fate) Akira $10 KISHU (PbtA) https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/319947/ See also Battle KISHU Angel: Alita. $11 Cybergeneration (CP2020) https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/25143/ ✓ Psychedemia (Fate) https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/142732/ Aladdin $50 City of Brass (5E) https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/266871/ Prince of City-of-Brass-5e Often goes on sale for significantly less. Persia, The $25 City of Brass (SW/OSR) https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/266876/ Etc. -

Shadowrun, Fifth Edition, Preview Two | Catalyst Game Labs

SHADOWRUN >noun Any movement, action, or series of such made in carrying out plans which are illegal or quasilegal. WorldWide WorldWatch 2050 archive INCOMING MESSAGE FROM M. WRATH: Hoi chummers! This is a preview of an in-progress version of Shadowrun, Fifth Edition, and proofing is still under way. Spelling, grammar, "p. XX" references and so on may be updated before heading to press. Get more info at www.shadowruntabletop.com SHADOwrun, fiftH eDitiOn • preview twO SECTION.02 SHADOWRUN CONCEPTS advancing the story, and the gamemaster should feel that THE GAME & YOU they can keep the story moving ahead without having to engage in prolonged and distracting discussions about As a player in a Shadowrun game, your primary objec- the rules. The more members of the group work together, tive is to make things happen. Many of those things the better their chances of shooting people in the face for should be awesome. The gamemaster will set up a story money in spectacular and amazing fashions will be. for you, then your character will decide how to respond For more advice on running a Shadowrun game and to the initial setup and all the events that happen once working with players, see Gamemaster Advice, p. 332. the story gets rolling. Sooner or later—hopefully soon- er—you’ll face a challenge, something that requires you to test your abilities. The rules are here so that you and HOW TO MAKE the gamemaster can determine the outcome of your ac- tions. Did the shot from your Ares Predator V hit the ork THINGS HAPPEN ganger right between the tusks? Are you able to sneak past the sleepy dwarf guard without waking him up? Did Your Shadowrun character does all the things a normal you counter the stunball the troll mage threw at you and person does, along with the occasional grand theft, dissolve it into millions of pieces of glittery mana? espionage mission, or hit job. -

POPULAR FRANCHISES AS TABLETOP RPGS Revision 10 (Apr.2021)

POPULAR FRANCHISES AS TABLETOP RPGS Revision 10 (Apr.2021) Franchise Free? Game Name Website .hack// ✓ Infinite Generation http://dothack.info/index.php?title=Category %3A.hack%2F%2FInfinite_Generation + Odds&Ends 3x3 Eyes ✓ 3x3 Eyes RPG (HERO, SN) http://surbrook.devermore.com/worldbooks/ 3x3eyes/3x3.html ✓ 3x3 Eyes (GURPS) https://web.archive.org/web/20001109020600/ http://www.dca.fee.unicamp.br/~henriqmh/ 3x3Eyes/RPG/ Huge listing of old anime http://www.oocities.org/timessquare/arena/ - RPGs 2448/about.html A Certain ✓ A Certain Roleplaying https://1d4chan.org/wiki/A_Certain_Role- Scientific Game playing_Game Railgun, Raildex $20 Demongate High https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/127312/ See also Smallville. (Paragon) https://yarukizerogames.com/2011/02/10/role- - Discussion play-this-a-certain-scientific-railgun/ Ace Attorney ✓ Abjection! https://www.reddit.com/r/AceAttorney/ comments/8zwgwa/ abjection_a_little_rpg_game_inspired_by_ace ✓ Cookie Jar https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/ 115517/Cookie-Jar https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/84260/ $12 Skullduggery Skulduggery ✓ Giant Allege: https://i.4pcdn.org/tg/1520114144592.pdf + Fan Translations https://projects.inklesspen.com/fatal-and- friends/professorprof/giant-allege/#6 “Heart-Pounding Robot Courtroom RPG" from Japan!” Adventure ✓ Adventure Time 4E www.mediafire.com/?ia9628cdx6zacwb + Time http://www.mediafire.com/file/ kmxkml5mzduc994/ AdventureTimeBeta_PrintFriendly.pdf/file “Though I’m not releasing a new version just for this, people reading this original post should