INTRODUCTION to 1 and 2 KINGS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloads/Jesuit Arabic Bible.Pdf 27 King James Version (KJV)

1 ©All rights reserved 2 Introduction Irenaeus, Polycarp, Papias New Testament Canonicity The Ten Papyri from the second century There is no co-called the original Gospel of the Four Gospels Anonymous Epistles within the New Testament A quick tour in the history of the New Testament The Gospel of John and the Greek Philosophy Were the scribes of the four Gospels, disciples of Jesus Christ? Who wrote the Gospel according to Matthew’s account? Who wrote the Gospel according to John’s account? Did the Holy Spirit inspire the four Gospels? Confessions of the Gospel of Luke The Church admits that there are forged additions in the New Testament The Gospel of Jesus Christ Who wrote the Old Testament? Loss of the Torah (Old Testament) Loss of a large number of the Bible's Books 3 In my early twenties, I have started my journey of exploring the world. I have visited many countries around the world and learnt about many different cultures and customs. I was shocked by the extent difference between the religions. I saw the Buddhist monks distancing themselves from the worldly life and devoting themselves to worshipping their god, Buddha. I saw the Christian monks isolating themselves in the monasteries and devoting themselves to worshipping their god, Jesus Christ. I saw those who worship trees, stones, cows, mice, fire, money and other inanimate objects, and I saw those who do not believe in the existence of God or they do believe in the existence of God, but they say, “We do not know anything about him.” I liked to hear from each one his point of view about what he worships. -

Books of the Bible and of the Apocrypha an Introduction

BOOKS OF THE BIBLE AND OF THE APOCRYPHA AN INTRODUCTION TO BIBLE APOCRYPHA (WITH A BIBLE HISTORY CHART AT THE END) Page 1-2: Introduction Historical controversy continues today among Bible students, researchers, scholars, and clergy about the subject of the Apocrypha; whether these "Bible-related" books are considered to be the very Word of God, or of historical reference accounts, or of uncertain origin and best kept on the shelf. Some Apocryphal books have even been marketed for sale as "Lost Books of the Bible". Essentially, Old Testament Apocrypha (14 books primarily) consists of Jewish documents that were not accepted into the Hebrew Bible / Old Testament as actual books of canon scripture, even though they were included in most of the early translations of the Bible (as far back as the Greek Septuagint), typically as a separate section after the Old Testament. Then there is the New Testament Apocrypha, which are writings attributed to Christians of the first four centuries in Christ but were not accepted into the New Testament either, and are very rarely included in any Bible. A summary introduction of each of the following charts is now presented. Page 3: Comparison of Modern Bibles Chart This chart compares a modern post-1885 KJV Bible with the 1970 Catholic New American Bible (NAB) translation and the difference is that the NAB still contains 10 of the original 14 OT Apocrypha books. The irony is that the pre-1885 KJV and earlier English translations contained all 14 Apocrypha books. What happened in 1885 to remove all Apocrypha from the KJV? The Latin Vulgate Bible of 405 A.D. -

Introduction to Eschatology

Introduction to Eschatology Prayer: We do not cease to thank you, 17 that the God of our Lord Jesus Christ, the Father of glory, may give to us the spirit of wisdom and revelation in the knowledge of Him, 18 that the eyes of your understanding would be enlightened; that we may intimately know the hope of Your calling and the riches of the glory of Your inheritance in us, 19 the exceeding greatness of His power toward the believers, according to the working of His mighty power 20 which He worked in Christ when You raised Him from the dead and seated Him at Your right hand in the heavens 21 far above all principality and power and might and dominion, and every name that is named, not only in this age but also in that which is to come. 22 And You put all things under His feet, and made Him head over all things to the church, 23 which is His body, the fullness of Him who fills all in all. (Eph 1:16-23) 25 Let us not refuse the voice of the Holy Spirit who speaks. For if they did not escape who refused Him in the past, much more shall we not escape if we turn away from Him who speaks now from heaven, 26 whose voice then shook the earth; but now He has promised, saying, "Once more I shake not only the earth, but also heaven." 27 Now this, "once more," indicates the removal of those things that can be shaken, as of things that are made, that the things which cannot be shaken may remain. -

Reader of 1 Corinthians 1 As to How It Was Applied

History and Authenticity of the Bible Lesson 14 Difficulties of Inspiration – Part Two By Dr. David Hocking Brought to you by The Blue Letter Bible Institute http://www.blbi.org A ministry of The Blue Letter Bible http://www.blueletterbible.org Lesson 14 HOCKING - HISTORY & AUTHENTICITY OF THE BIBLE Page 1 of 20 “Difficulties of Inspiration” - Part Two We are dealing with these five problems and you will find them in almost every textual criticism book. That’s why I want you to just know what they are. Difficulties in Transmission of the Text 1. Inexact Quotations 2. Variant Reports 3. Contradictory Statements 4. Unscientific Expressions 5. Human Errors I’m not going to expect you to know a lot of details, but let’s start with a basic one that comes up often—inexact quotations. There are many of them. I gave you an example out of Isaiah 40:3, matching Matthew 3:3, “Prepare ye the way of the Lord, make straight His path.” And you can see that there’s just a little variation in how it’s stated. Well, literally scores and scores of Old Testament quotations are like that in the New Testament. They are not quoted exactly. Now some people say, “Well maybe they are quoted off of the Greek Old Testament rather than the Hebrew, like the Septuagint.” That’s a big promoted thing among a lot of guys. A lot of pastors think that’s the deal. I think that is hustling too much. That’s like trying to “strain at a gnat” a little too much (cf. -

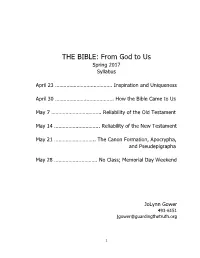

Syllabus and Text

THE BIBLE: From God to Us Spring 2017 Syllabus April 23 …………………………………. Inspiration and Uniqueness April 30 ………………….………………. How the Bible Came to Us May 7 …………………………….. Reliability of the Old Testament May 14 ………………………….. Reliability of the New Testament May 21 ……………………….. The Canon Formation, Apocrypha, and Pseudepigrapha May 28 ………………..………. No Class; Memorial Day Weekend JoLynn Gower 493-6151 [email protected] 1 INSPIRATION AND UNIQUENESS The Bible continues to be the best selling book in the World. But between 1997 and 2007, some speculate that Harry Potter might have surpassed the Bible in sales if it were not for the Gideons. This speaks to the world in which we now find ourselves. There is tremendous interest in things that are “spiritual” but much less interest in the true God revealed in the Bible. The Bible never tries to prove that God exists. He is everywhere assumed to be. Read Exodus 3:14 and write what you learn: ____________________________ _________________________________________________________________ The God who calls Himself “I AM” inspired a divinely authorized book. The process by which the book resulted is “God-breathed.” The Spirit moved men who wrote God-breathed words. Read the following verses and record your thoughts: 2 Timothy 3:16-17__________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________ Do a word study on “scripture” from the above passage, and write the results here: ____________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________ -

Overview of the Bible

Christian Resource Center – New Hampshire (www.crcnh.org) Overview of the Bible Where Did the Bible Come From? The Bible is the most important and most published book that has ever been possessed by mankind. It is the only book comprised of texts that were given to mankind directly by God. Everything that we need to know about spiritual, familial, and civil institutions as well as how to live a joyful and righteous life is contained within the 66 books of the bible. A huge portion of the bible points to the salvation that would come to humanity through the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. Below are some interesting biblical statistics. Bible Statistics (approximate) Data Total number of bibles printed 6,001,500,000 Approximate number of languages spoken in the 6,900 world today. Number of translations into new languages 1,300 currently in progress. Number of languages with a translation of the New 1,185 Testament. Number of languages with a translation of the 451 entire Bible. (Protestant Canon) Total Words in the King James Bible 788,258 Number of verses in the King James Bible 31,102 Total Chapters in the King James Bible 1,189 Total Books in the King James Bible 66 Total Number of Authors in the Bible 40 Years it took to write the Bible 1,600 Shortest Chapter Psalm 117 (2 verses) Longest Chapter Psalm 119 Middle Chapter Psalm 117 (the 595th chapter) Shortest Verse in the Bible John 11:35 – “Jesus wept.” Longest Verse in the Bible Esther 8:9 Please Make Copies and Distribute Freely Christian Resource Center – New Hampshire (www.crcnh.org) [2 Timothy 3:16-17] All Scripture is given by inspiration of God, and is profitable for doctrine, for reproof, for correction, for instruction in righteousness, that the man of God may be complete, thoroughly equipped for every good work. -

8 – the Lost Books of the Bible

8 – The Lost Books of the Bible Canonical Books: “Canon” comes from the Greek meaning “rule” or “measuring stick”. The accepted “canon” is comprised of the current 66 books in the Christian Bible. All 66 books are considered to be inspired by God. Proto-Canonical – “Proto” comes from the Greek meaning “first”. These books are the “first canon” and include the 39 Old Testament books that were the basis for the Hebrew bible. Deutero-Canonical – “Deutero” comes from the Greek meaning “second”. These books are the “second www.crcnh.org canon” and include the 27 New Testament books written in Greek. Non-Canonical Books: These are any “religious” book not included in the 66 books of the canon. They are referred to synonymously as either “apochryphal” or “pseudoepigraphal”. These books are not inspired by God. Apocrypha – From the Greek “apo” meaning “away” and “kryphos” meaning “hidden” (hidden away). These are works of unknown authorship or have doubtful authenticity. Pseudoepigrapha – Comes from the Greek “pseudes” meaning “false” and “epigraphe” meaning “name” (false name). These are works that are written by one author but are claimed to have originated earlier by an unknown author. Original King James Apocryphal Books* Other Apochryphal and Pseudoepigrapha Books 1. 1st Esdras 9. Letter of Jeremiah 1. Ascension of Moses 9. Letter of Aristias 2. 2nd Esdras 10. Prayer of Azariah 2. Book of Assaf 10. Vision of Ezra 3. Tobit 11. Susanna 3. Book of Noah 11. Treatise of Shem 4. Judith 12. Bel and the Dragon 4. Book of Adam & Eve 12. Ladder of Jacob 5. -

Reading 4 Chapter 8 the Babe of Bethlehem the Birth of Jesus Equally Definite with the Prophecies Declaring That the Messiah

Reading 4 Chapter 8 The Babe of Bethlehem The Birth of Jesus Equally definite with the prophecies declaring that the Messiah would be born in the lineage of David are the predictions that fix the place of His birth at Bethlehem, a small town in Judea. There seems to have been no difference of opinion among priests, scribes, or rabbis on the matter, either before or since the great event. Bethlehem, though small and of little importance in trade or commerce, was doubly endeared to the Jewish heart as the birthplace of David and as that of the prospective Messiah. Mary and Joseph lived in Nazareth of Galilee, far removed from Bethlehem of Judea; and, at the time of which we speak, the maternity of the Virgin was fast approaching. At that time a decree went out from Rome ordering a taxing of the people in all kingdoms and provinces tributary to the empire; the call was of general scope, it provided “that all the world should be taxed.”a The taxing herein referred to may properly be understood as an enrolment,b or a registration, whereby a census of Roman subjects would be secured, upon which as a basis the taxation of the different peoples would be determined. This particular census was the second of three such general registrations recorded by historians as occurring at intervals of about twenty years. Had the census been taken by the usual Roman method, each person would have been enrolled at the town of his residence; but the Jewish custom, for which the Roman law had respect, necessitated registration at the cities or towns claimed by the respective families as their ancestral homes. -

How We Got the Bible

Digging Deeper Links from the Discussion Guide for HOW WE GOT THE BIBLE LESSON 1 HOW WERE THE BOOKS OF THE BIBLE FIRST WRITTEN? The earliest books of the Bible (including Genesis-Deuteronomy, the five books of Moses) were written on papyrus made from plants growing along the Nile River. Papyrus could be formed into long sheets and rolled up onto scrolls. Writing could only be done on one side of the papyrus. Video demonstration: How Papyrus is Made Later books (including many in the New Testament) were written on animal skins called parchment or vellum. (2 Timothy 4:13). Writers could use both sides of parchment and vellum. These sheets were folded into a small booklet called a ―codex.‖ In the days when the New Testament was being written the largest codex could hold the four Gospels—Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. Video demonstration – Dirty Jobs- Making Vellum & Parchment Other Information: The Difference between Paper, Parchment & Vellum How the Sumerians started writing Writing before the alphabet Was the alphabet invented on Mt. Sinai? How the Christian church kept literacy alive in the Middle Ages Where were the copies made? Scriptoria. BIBLE IMAGES This site includes scanned images of old Bibles for you to peruse. LESSON 2 THE INSPIRATION OF SCRIPTURE The Report on the Inspiration of Scripture from the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod’s Commission on Theology and Church Relations (CTCR). THE EFFECT OF FALSE PRESUPPOSITIONS Bruno Bauer’s impact on Socialism’s Rejection of Christianity The impact the 18th-century German attack on the Bible had on Islamic Apologetics Quest for the Historical Jesus and the Authenticity of Scripture ERRORS IN THE DA VINCI CODE ―When someone presupposes that the miraculous is impossible, all evidence is dismissed and denied in the first place‖ (Dr. -

The Lost Books of the Bible

The Lost Books of the Bible Books Mentioned, But Not Found, In The Bible There are twenty-two books mentioned in the Bible, but not included. The variation is due to possible double mentions using differing names for the same book. Book of the Covenant Exodus 24:7 And he took the book of the covenant, and read in the audience of the people: and they said, All that the Lord hath said will we do, and be obedient. There are those that believe the Book of the Covenant is found in Exodus chapters 20 through 23. There are no authoritative sources for this text. Book of the Wars of the Lord Numbers 21:14 Wherefore it is said in the book of the wars of the Lord, What he did in the Red sea, and in the brooks of Arnon, Certain sources believe that this is to be found by drawing text from several Old Testament books. There are no authoritative sources for this text. Book of Jasher Here We have the entire book on this site Here Joshua 10:13 And the sun stood still, and the moon stayed, until the people had avenged themselves upon their enemies. Is not this written in the book of Jasher? So the sun stood still in the midst of heaven, and hasted not to go down about a whole day. 2 Samuel 1:18 (Also he bade them teach the children of Judah the use of the bow: behold, it is written in the book of Jasher.) The Manner of the Kingdom / Book of Statutes 1 Samuel 10:25 Then Samuel told the people the manner of the kingdom, and wrote it in a book, and laid it up before the Lord. -

The Walls of Jericho Joshua 6-10

Lesson 76 The Walls of Jericho Joshua 6-10 “Now while the Israelites did this, and the Canaanites did not attack them, but kept themselves quiet within their own walls, Joshua resolved to besiege them…” Josephus Standards That Might Be Hard to Keep “You should not date “Do not disfigure yourself with until you are at least 16 tattoos or body piercings. Young years old. … Avoid going women, if you desire to have your on frequent dates with ears pierced, wear only one pair of the same person.” earrings.” “Honoring the Sabbath day What other commandments or standards includes attending all your Church has the Lord given that some may question meetings. … Sunday is not a day for shopping, recreation, or the importance of? athletic events.” (1) Unusual Tactics For Battle As the Israelites entered the land of Canaan, the Lord gave them unusual commandments or instructions for how they were to attack the well-fortified city of Jericho. To some of the Israelites, these commandments may have seemed strange or unreasonable. Joshua 6:1-5 Compass the City First came the army of Israel. Then 7 priests blowing trumpets. Then the Ark of the Covenant. Last a special guard bring up Jericho the rear They marched everyday, once around the wall for 6 days Only the sound of the trumpets could be heard Joshua 6:3-14 The 7th Day They marched around 7 times …only Rahab the harlot shall live, she and all that are with her in the house, because she hid the messengers that we sent. -

Del Rey Bible Institute Fides Quaerens Intellectum

Del Rey Bible Institute Fides Quaerens Intellectum SCRIPTURE & HERMENEUTICS THE CASE FOR THE BIBLE1 The Uniqueness of the Bible CHAPTER OVERVIEW Introduction Unique in Its Continuity Unique in Its Circulation Unique in Its Translation Unique in Its Survival Through Time Through Persecution Through Criticism Unique in Its Teachings Prophecy History Character Unique in Its Influence on Literature Unique in Its Influence on Civilization A Reasonable Conclusion INTRODUCTION 1 Josh McDowell, Evidence for Christianity (Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson Publishers, 2006), 17-60. Over and over again, like a broken record, people ask me, “Oh, you don’t read the Bible, do you?” Sometimes they’ll say, “Why, the Bible is just another book; you ought to read…” Then they’ll mention a few of their favorite books. There are those who have a Bible in their library. They proudly tell me that it sits on the shelf next to other “greats,” such as Homer’s Odyssey or Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet or Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. Their Bible may be dusty, not broken in, but they still think of it as one of the classics. Others make degrading comments about the Bible, even snickering at the thought that anyone might take it seriously enough to spend time reading it. For these folks, having a copy of the Bible in their library is a sign of ignorance. The above questions and observations bothered me when, as a non-Christian, I tried to refute the Bible as God’s Word to humanity. I finally came to the conclusion that these were simply trite phrases from biased, prejudiced, or simply unread men and women.