Identification of Historic Apple Trees in the Southwestern United States and Implications for Conservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

APPLE (Fruit Varieties)

E TG/14/9 ORIGINAL: English DATE: 2005-04-06 INTERNATIONAL UNION FOR THE PROTECTION OF NEW VARIETIES OF PLANTS GENEVA * APPLE (Fruit Varieties) UPOV Code: MALUS_DOM (Malus domestica Borkh.) GUIDELINES FOR THE CONDUCT OF TESTS FOR DISTINCTNESS, UNIFORMITY AND STABILITY Alternative Names:* Botanical name English French German Spanish Malus domestica Apple Pommier Apfel Manzano Borkh. The purpose of these guidelines (“Test Guidelines”) is to elaborate the principles contained in the General Introduction (document TG/1/3), and its associated TGP documents, into detailed practical guidance for the harmonized examination of distinctness, uniformity and stability (DUS) and, in particular, to identify appropriate characteristics for the examination of DUS and production of harmonized variety descriptions. ASSOCIATED DOCUMENTS These Test Guidelines should be read in conjunction with the General Introduction and its associated TGP documents. Other associated UPOV documents: TG/163/3 Apple Rootstocks TG/192/1 Ornamental Apple * These names were correct at the time of the introduction of these Test Guidelines but may be revised or updated. [Readers are advised to consult the UPOV Code, which can be found on the UPOV Website (www.upov.int), for the latest information.] i:\orgupov\shared\tg\applefru\tg 14 9 e.doc TG/14/9 Apple, 2005-04-06 - 2 - TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. SUBJECT OF THESE TEST GUIDELINES..................................................................................................3 2. MATERIAL REQUIRED ...............................................................................................................................3 -

Variety Description Origin Approximate Ripening Uses

Approximate Variety Description Origin Ripening Uses Yellow Transparent Tart, crisp Imported from Russia by USDA in 1870s Early July All-purpose Lodi Tart, somewhat firm New York, Early 1900s. Montgomery x Transparent. Early July Baking, sauce Pristine Sweet-tart PRI (Purdue Rutgers Illinois) release, 1994. Mid-late July All-purpose Dandee Red Sweet-tart, semi-tender New Ohio variety. An improved PaulaRed type. Early August Eating, cooking Redfree Mildly tart and crunchy PRI release, 1981. Early-mid August Eating Sansa Sweet, crunchy, juicy Japan, 1988. Akane x Gala. Mid August Eating Ginger Gold G. Delicious type, tangier G Delicious seedling found in Virginia, late 1960s. Mid August All-purpose Zestar! Sweet-tart, crunchy, juicy U Minn, 1999. State Fair x MN 1691. Mid August Eating, cooking St Edmund's Pippin Juicy, crisp, rich flavor From Bury St Edmunds, 1870. Mid August Eating, cider Chenango Strawberry Mildly tart, berry flavors 1850s, Chenango County, NY Mid August Eating, cooking Summer Rambo Juicy, tart, aromatic 16th century, Rambure, France. Mid-late August Eating, sauce Honeycrisp Sweet, very crunchy, juicy U Minn, 1991. Unknown parentage. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Burgundy Tart, crisp 1974, from NY state Late Aug.-early Sept. All-purpose Blondee Sweet, crunchy, juicy New Ohio apple. Related to Gala. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Gala Sweet, crisp New Zealand, 1934. Golden Delicious x Cox Orange. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Swiss Gourmet Sweet-tart, juicy Switzerland. Golden x Idared. Late Aug.-early Sept. All-purpose Golden Supreme Sweet, Golden Delcious type Idaho, 1960. Golden Delicious seedling Early September Eating, cooking Pink Pearl Sweet-tart, bright pink flesh California, 1944, developed from Surprise Early September All-purpose Autumn Crisp Juicy, slow to brown Golden Delicious x Monroe. -

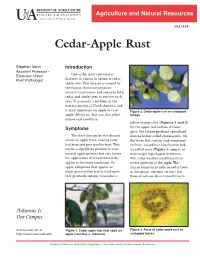

Cedar-Apple Rust

DIVISION OF AGRICULTURE RESEARCH & EXTENSION Agriculture and Natural Resources University of Arkansas System FSA7538 Cedar-Apple Rust Stephen Vann Introduction Assistant Professor One of the most spectacular Extension Urban Plant Pathologist diseases to appear in spring is cedar- apple rust. This disease is caused by the fungus Gymnosporangium juniperi-virginianae and requires both cedar and apple trees to survive each year. It is mainly a problem in the eastern portion of North America and is most important on apple or crab Figure 2. Cedar-apple rust on crabapple apple (Malus sp), but can also affect foliage. quince and hawthorn. yellow-orange color (Figures 1 and 2). Symptoms On the upper leaf surface of these spots, the fungus produces specialized The chief damage by this disease fruiting bodies called spermagonia. On occurs on apple trees, causing early the lower leaf surface (and sometimes leaf drop and poor quality fruit. This on fruit), raised hair-like fruiting bod can be a significant problem to com ies called aecia (Figure 3) appear as mercial apple growers but also harms microscopic cup-shaped structures. the appearance of ornamental crab Wet, rainy weather conditions favor apples in the home landscape. On severe infection of the apple. The apple, symptoms first appear as fungus forms large galls on cedar trees small green-yellow leaf or fruit spots in the spring (see next section), but that gradually enlarge to become a these structures do not greatly harm Arkansas Is Our Campus Visit our web site at: Figure 1. Cedar-apple rust (leaf spot) on Figure 3. Aecia of cedar-apple rust on https://www.uaex.uada.edu apple (courtesy J. -

Apples: Organic Production Guide

A project of the National Center for Appropriate Technology 1-800-346-9140 • www.attra.ncat.org Apples: Organic Production Guide By Tammy Hinman This publication provides information on organic apple production from recent research and producer and Guy Ames, NCAT experience. Many aspects of apple production are the same whether the grower uses low-spray, organic, Agriculture Specialists or conventional management. Accordingly, this publication focuses on the aspects that differ from Published nonorganic practices—primarily pest and disease control, marketing, and economics. (Information on March 2011 organic weed control and fertility management in orchards is presented in a separate ATTRA publica- © NCAT tion, Tree Fruits: Organic Production Overview.) This publication introduces the major apple insect pests IP020 and diseases and the most effective organic management methods. It also includes farmer profiles of working orchards and a section dealing with economic and marketing considerations. There is an exten- sive list of resources for information and supplies and an appendix on disease-resistant apple varieties. Contents Introduction ......................1 Geographical Factors Affecting Disease and Pest Management ...........3 Insect and Mite Pests .....3 Insect IPM in Apples - Kaolin Clay ........6 Diseases ........................... 14 Mammal and Bird Pests .........................20 Thinning ..........................20 Weed and Orchard Floor Management ......20 Economics and Marketing ........................22 Conclusion -

Treeid Variety Run 2 DNA Milb005 American Summer Pearmain

TreeID Variety Run 2 DNA Run 1 DNA DNA Sa… Sourc… Field Notes milb005 American Summer Pearmain/ "Sara's Polka American Summer Pearmain we2g016 AmericanDot" Summer Pearmain/ "Sara's Polka American Summer Pearmain we2f017 AmericanDot" Summer Pearmain/ "Sara's Polka American Summer Pearmain we2f018 AmericanDot" Summer Pearmain/ "Sara's Polka American Summer Pearmain eckh001 BaldwinDot" Baldwin-SSE6 eckh008 Baldwin Baldwin-SSE6 2lwt007 Baldwin Baldwin-SSE6 2lwt011 Baldwin Baldwin-SSE6 schd019 Ben Davis Ben Davis mild006 Ben Davis Ben Davis wayb004 Ben Davis Ben Davis andt019 Ben Davis Ben Davis ostt014 Ben Davis Ben Davis watt008 Ben Davis Ben Davis wida036 Ben Davis Ben Davis eckg002 Ben Davis Ben Davis frea009 Ben Davis Ben Davis frei009 Ben Davis Ben Davis frem009 Ben Davis Ben Davis fres009 Ben Davis Ben Davis wedg004 Ben Davis Ben Davis frai006 Ben Davis Ben Davis frag004 Ben Davis Ben Davis frai004 Ben Davis Ben Davis fram006 Ben Davis Ben Davis spor004 Ben Davis Ben Davis coue002 Ben Davis Ben Davis couf001 Ben Davis Ben Davis coug008 Ben Davis Ben Davis, error on DNA sample list, listed as we2a023 Ben Davis Bencoug006 Davis cria001 Ben Davis Ben Davis cria008 Ben Davis Ben Davis we2v002 Ben Davis Ben Davis we2z007 Ben Davis Ben Davis rilcolo Ben Davis Ben Davis koct004 Ben Davis Ben Davis koct005 Ben Davis Ben Davis mush002 Ben Davis Ben Davis sc3b005-gan Ben Davis Ben Davis sche019 Ben Davis, poss Black Ben Ben Davis sche020 Ben Davis, poss Gano Ben Davis schi020 Ben Davis, poss Gano Ben Davis ca2e001 Bietigheimer Bietigheimer/Sweet -

A Manual Key for the Identification of Apples Based on the Descriptions in Bultitude (1983)

A MANUAL KEY FOR THE IDENTIFICATION OF APPLES BASED ON THE DESCRIPTIONS IN BULTITUDE (1983) Simon Clark of Northern Fruit Group and National Orchard Forum, with assistance from Quentin Cleal (NOF). This key is not definitive and is intended to enable the user to “home in” rapidly on likely varieties which should then be confirmed in one or more of the manuals that contain detailed descriptions e.g. Bunyard, Bultitude , Hogg or Sanders . The varieties in this key comprise Bultitude’s list together with some widely grown cultivars developed since Bultitude produced his book. The page numbers of Bultitude’s descriptions are included. The National Fruit Collection at Brogdale are preparing a list of “recent” varieties not included in Bultitude(1983) but which are likely to be encountered. This list should be available by late August. As soon as I receive it I will let you have copy. I will tabulate the characters of the varieties so that you can easily “slot them in to” the key. Feedback welcome, Tel: 0113 266 3235 (with answer phone), E-mail [email protected] Simon Clark, August 2005 References: Bultitude J. (1983) Apples. Macmillan Press, London Bunyard E.A. (1920) A Handbook of Hardy Fruits; Apples and Pears. John Murray, London Hogg R. (1884) The Fruit Manual. Journal of the Horticultural Office, London. Reprinted 2002 Langford Press, Wigtown. Sanders R. (1988) The English Apple. Phaidon, Oxford Each variety is categorised as belonging to one of eight broad groups. These groups are delineated using skin characteristics and usage i.e. whether cookers, (sour) or eaters (sweet). -

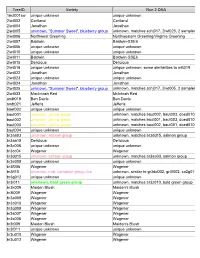

MORP DNA Results Treeid

TreeID Variety Run 2 DNA Run 1 DNA DNA Sa… Sourc… Field Notes 1bct001sw unique unknown unique unknown 2lwt002 Cortland Cortland 2lwt004 Jonathan Jonathan 2lwt005 unknown, "Summer Sweet", blueberry group unknown, matches schj017, 2lwt025, 2 samples 2lwt006 Northwest Greening NorthwesternUniversity of WY, Greening/Virginia blueberry group Greening 2lwt007 Baldwin Baldwin-SSE6 2lwt00b unique unknown unique unknown 2lwt010 unique unknown unique unknown 2lwt011 Baldwin Baldwin-SSE6 2lwt015 Delicious Delicious 2lwt016 unique unknown unique unknown, some similarities to wilt019 2lwt022 Jonathan Jonathan 2lwt023 unique unknown unique unknown 2lwt024 Jonathan Jonathan 2lwt025 unknown, "Summer Sweet", blueberry group unknown, matches schj017, 2lwt005, 2 samples 2lwt033 MacIntosh Red McIntoshUniversity Red of WY, blueberry group andt019 Ben Davis Ben Davis andt021 Jefferis Jefferis baef002 unique unknown unique unknown baut001 unknown, yellow group unknown, matches baut002, baut003, doed010, baut002 unknown, yellow group unknown,San_Isabel, matches but with baut001, incomplete baut003, data, yellowdoed010, baut003 unknown, yellow group unknown,San_Isabel, matches but with baut002, incomplete baut001, data, yellowdoed010, baut004 unique unknown uniqueSan_Isabel, unknown but with incomplete data, yellow br3aa03 unknown, salmon group unknown, matches br3dd15, salmon group br3aa15 Delicious Delicious br3c006 unique unknown unique unknown br3cc04 Wagener Wagener br3dd15 unknown, salmon group unknown, matches br3aa03, salmon group br3e009 unique unknown -

Progress in Apple Improvement

PROGRESS IN APPLE IMPROVEMENT J. R. MAGNESS, Principal Pomologisi, 13ivision of Fruit and Vegetable Crops and Diseases, liureau of Plant Industry ^ A HE apple we liave today is J^u" rciuovod from tlic "gift of the gods'' wliich prehistoric man found in roaming the woods of western Asia and temperate Europe. We can judge that apple only by the wild apples that grow today in the area between tlie Caspian Sea and Europe, which is believed to be the original habitat of the apple. These apples are generally onl>r 1 to 2 inches in diameter, are acici and astringent, and are far inferior io the choice modern horticultural varieties. The improvement of the apple through tlie selection of the best types of the wild seedlings goes far baclv to the very beginning of history. Methods of budding and grafting fiiiits were Icnown more than 2,000 years ago. According to linger, C^ato (third century, B. C.) knew seven different apple varieties, l^liny (first centiuy, A. D.) knew^ 36 different kinds. By tlie time the iirst settlers froni Europe were coming to the sliores of North America., himdreds of apple varieties had been named in European <M)unt]*ies, The superior varieties grown in l^^urope in the seventeenth century had, so far as is known, all developed as chance seedlings, but garden- ers had selected the best of the s(>edling trees îvnd propagated them vegetatively. The early American settlers, ptirticiilarly those from the temperate portions of Europe, who came to the eastern coast of North Amer- ica, brought with them seeds and in some cases grafted trees of European varieties. -

Inaugural Issue

THE ORTET Inaugural Issue Midwest Apple Improvement Association Autumn 2015 Newsletter MAIA Board of Directors IN THIS ISSUE Gregg Bachman Sunny Hill Fruit Farm, Carroll, OH 3 A Message from the Chairman Felix Cooper Garden’s Alive!, Tipp City, OH 4 President’s Report David Doud Countyline Orchard, Wabash, IN 5 MAIA Apple Evaluation iPad App Jim Eckert Eckert Orchards, Belleville, IL 6 An Embarrassment of Riches Allen Grobe Grobe Fruit Farm, Elyria, OH 7 An Article from the Archives David Hull White House Fruit Farm, Canfield, OH 8 Fall Taste Evaluations Dano Simmons Peace Valley Orchard, Rogers, OH 13 Apple Crunch Day Andy Lynd Lynd Fruit Farm, Pataskala, OH 14 Apples for New Era MAIA Advisors Mitch Lynd Lynd Fruit Farm, Pataskala, OH Dr. Diane Miller The Ohio State University Bill Dodd Hillcrest Orchard, Amherst, OH Newsletter Staff, Ciderwood Press Amy Miller, Editor-in-Chief Midwest Apple Improvement Association Matt Thomas, Creative Director P.O. Box 70 Kathryn Everson, Layout Editor Newcomerston, OH 43832 (800) 446 - 5171 To obtain the EverCrisp® licens- To find out how to become a member, learn ing agreement and learn more about more about our history, read past newsletters, MAIA1 go to: and more, go to: evercrispapple.com midwestapple.com 2 A Message from the Chairman Greetings All, ometimes we find value in unexpected places. An example S of this at our farm market is a used Pease apple peeler we bought several years ago to make peeling more efficient in our bakery. After a few weeks of using the peeler, the girls found that they liked their smaller household peelers better than using the bigger, although more efficient, peeler. -

Different Methods of Thinning Influenced by Variety and Hail Nets in Apple Orchards

Research Article Agri Res & Tech: Open Access J Volume 22 Issue 3 - August 2019 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Ricardo Antonio Ayub DOI: 10.19080/ARTOAJ.2019.22.556197 Different Methods of Thinning Influenced by Variety and Hail Nets in Apple Orchards Alexandre Pozzobom Pavanello1,2, Michael Zoth2, Ricardo Antonio Ayub1* and Kamila Karoline de Souza Los1 1Depto de Fitotecnia Universidade Estadual de Ponta Grossa, Brazil 2Kopetemzzentrum Obstbau Bodansee, Germany Submission: July 23, 2019; Published: August 20, 2019 *Corresponding author: Ricardo Antonio Ayub, Depto de Fitotecnia, Universidade Estadual de Ponta Grossa, UEPG, , Av. Carlos Cavalcanti, 4748, 84030900, Ponta Grossa-PR, Brazil Abstract Looking at the effects of thinning on apple quality, the purpose of this study was to investigate the fallouts of thinning methods in different varieties and under hail nets. The experiment was developed in Bavendorf, South Germany. The ‘Pinova’and ‘Braeburn’ apple trees were covered with two types of hail net: white, black and without nets. The following thinners were tested: Mechanical thinning (MT) with the ‘Darwin machine’; chemical thinning with Metamitron (CT-Metamitron) or 6-benzyladenine (CT-BA) and hand thinning (HT). The evaluations were: fruit set, time taken for HT, photosynthesis measurements, fruit retention, yield, fruit quality, and thinning efficacy value. The CT-BA treatment required the highest number of hours to perform HT for both varieties and hail nets. Comparing the varieties, the Pinova demonstrated less efficiency for thinning treatments, hence more hours were needed to thin by hand. Photosynthesis measurements were clearly different between CT-Metamitron versus CT-BA and MT curves, where CT-Metamitron remained in effect for 11 days after the treatment. -

Bayfieldberryfarm-Orchardguide

TOUR the FRUIT LOOP! Follow Cnty. Hwy. J just north and south of Bayfield, or take Washington Ave. from downtown and discover a wealth of fruits, berries and fresh produce! Be sure to spend some time meandering the backroads, including Valley Rd. and Betzold Rd., on the hills above Bayfield - the roadsides are dotted with farm stands and orchard shops, just waiting for you to discover them. GUIDEGUIDE JOIN US for APPLE FESTIVAL! Every autumn, the growing season culminates with a three-day celebration of the regions’s agricultural heritage, the Bayfield Apple Festival. Known locally as Applefest, the event features local foods, arts and crafts booths and live entertainment provided by the Blue Canvas Orchestra of Big Top Chautuaqua. And, of course, apples! It begins on the first Friday in October and is consistently rated as one of the top fall harvest festivals in the nation. Special events include the coronation of the Apple Festival Queen, who is chosen from Bayfield’s orchard families, an apple peeling contest, and the Grand Parade on Sunday afternoon. #BAYFIELDAPPLEFEST Surrounded by family farms and orchards, an exploration FRESH FRUIT & BERRY AVAILABILITY • ALL DATES ARE APPROXIMATE • of local food culture begins with a tour of the Fruit Loop, JUNE JULY AUGUST SEPTEMBER OCTOBER which winds its way around the city of Bayfield. STRAWBERRIES Bayfield’s location near Lake Superior and the Apostle Islands creates a unique CURRANTS micro-climate, which allows fruits and berries to flourish on the land surrounding JUNEBERRIES the city. During the summer months, you can find fresh strawberries, sweet and tart cherries, raspberries, blueberries and blackberries at the downtown farmers CHERRIES GRAPES market every Saturday morning and at roadside stands along the Fruit Loop. -

L 1,11 Ni * Li' ! ' ){[' 'Il 11'L'i J)[ Inhoud

mmMmm ;)l 1,11 ni * li' ! ' ){[' 'il 11'l'i j)[ Inhoud biz. 2 Inleiding 4 Aanwijzingen voor het gebruik 6 Het Nederlands Rassenregister en het Kwekersrecht 7 Grootfruit 8 - Inleiding 8 - Het gebruikswaardeonderzoek 9 - Plantmateriaal 14 - Bestuiving 18 - Bloeitijdengrafieken, bestuivingstabellen en -driehoeken 34 - Appel 86 - Peer 108 - Pruim 120 - Kers 137 Kleinfruit 139 - Inleiding 139 - Gebruikswaardeonderzoek 140 - Plantmateriaal 142 - Bestuiving 143 - Aardbei 165 - Blauwe bes 177 - Braam 186 - Framboos 197 - Kruisbes 206 - Rode bes 223 - Witte bes 231 - Zwarte bes 240 Noten 241 - Hazelaar 251 - Walnoot 256 Windschermen in de fruitteelt 260 Grassen voor rijstroken 265 Adressen van relevante instellingen 268 Register Rassenlijsten 1 t/m 18 284 Rassenregister 18e Rassenlijst 287 Uitgaven voor de Fruitteelt 18e RASSENLIJST voor Fruitgewassen 1992 CRF De Rassenlijst voor Fruitgewassen wordt samengesteld onder verant woordelijkheid van de Commissie voor de samenstelling van de Ras senlijst voor Fruitgewassen (CRF). Deze commissie is ingesteld bij Ko ninklijk Besluit van 10 mei 1967 (Staatsblad 268, d.d. 30 mei 1967). Zij is gevestigd te Wageningen en bestaat uit: ir. H.T.J. Peelen (voorzitter); ir. C.A.A.A. Maenhout (vice-voorzitter); ir. J.J. Bakker (secretaris); ir. R.K. Elema, ing. C.G.M. van Leeuwen en vacature (leden); ir. R.J.M. Meijer (adviserend lid). De taak van de commissie, de eisen waaraan de rassenlijst moet vol doen en de regels van procedurele aard zijn vastgesteld in hoofdstuk V, de artikelen 73 t/m 79 van de Zaaizaad- en Plantgoedwet, in het bo vengenoemd Besluit en in de Beschikking houdende inrichting van de Beschrijvende Rassenlijst voor Fruitgewassen van 18 mei 1967 (Staatscourant 98).