Regional Organization and the Dynamics of Inter-Municipal Cooperation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Core 1..120 Hansard (PRISM::Advent3b2 17.25)

House of Commons Debates VOLUME 148 Ï NUMBER 098 Ï 1st SESSION Ï 42nd PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Wednesday, October 26, 2016 Speaker: The Honourable Geoff Regan CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) 6133 HOUSE OF COMMONS Wednesday, October 26, 2016 The House met at 2 p.m. I met a woman entrepreneur, innovating for the success of her small business, and children striving toward excellence. They are future doctors, lawyers, and tradespeople. I saw it in their eyes; if they get the opportunity, they will succeed. Prayer I speak from experience. Twenty-five years ago, I was a girl child striving for opportunity in a developing country, uniform dusty but Ï (1400) eyes gleaming. [Translation] Today I am even more committed to working with the Minister of The Speaker: It being Wednesday, we will now have the singing International Development and La Francophonie to further the of the national anthem led by the hon. member for Hochelaga. partnership between Canada, Kenya, and other African nations. As a [Members sang the national anthem] donor country, Africa is and should remain a priority for us. *** Ï (1405) STATEMENTS BY MEMBERS BARRIE [Translation] Mr. John Brassard (Barrie—Innisfil, CPC): Mr. Speaker, the TAX HAVENS Canadian Federation of Independent Business recently named Barrie the third most progressive city, out of 122 in the country, for Mr. Gabriel Ste-Marie (Joliette, BQ): Mr. Speaker, today is a entrepreneurial start-ups in 2016. historic day. For the first time, we, the people's representatives, will vote either for or against tax havens. -

2009-2012 Barrie Advance Ca

COLLECTIVE AGREEMENT between METROLAND MEDIA GROUP LTD. - and - COMMUNICATIONS, ENERGY AND PAPERWORKERS UNION OF CANADA SOUTHERN ONTARIO NEWSMEDIA GUILD LOCAL 87-M BARRIE ADVERTISING SALES DEPARTMENTS Ratified February 8, 2010 August 31, 2009 to August 31, 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS LOCAL HISTORY 5 PREAMBLE 10 ARTICLE 1 – RELATIONSHIP 10 1.01 Recognition 10 1.02 Union Membership 10 1.03 Deduction of Union Dues 10 ARTICLE 2 – MANAGEMENT RIGHTS 10 ARTICLE 3 – NEW EMPLOYEES 11 3.01 Probationary Period 11 ARTICLE 4 – PART-TIME & TEMPORARY EMPLOYEES 11 4.01 Part-time Employees 11 4.02 Excluded Clauses 11 4.03 Part-time Benefits 11 4.04 Working Full-time Hours 12 4.05 Part-time Wages 12 4.06 Temporary Employees 12 4.07 Excluded Clauses 12 4.08 Temporary Seniority 12 ARTICLE 5 – INFORMATION 12 ARTICLE 6 – NO STRIKE OR LOCK-0UT 13 ARTICLE 7 – NO DISCRIMINATION 13 ARTICLE 8 – STEWARDS 13 ARTICLE 9 – GRIEVANCE PROCEDURE 13 ARTICLE 10 – ARBITRATION 15 ARTICLE 11 – HEALTH & SAFETY 16 ARTICLE 12 – JOB POSTINGS 16 12.01 Posting and Selection 16 12.02 Trial Period 16 ARTICLE 13 – DISCIPLINE & DISCHARGE 17 2 13.01 Just Cause 17 13.02 Discharge Grievance 17 13.03 Employee Files 17 ARTICLE 14 – TERMINATION 17 14.01 Continuity of Service 17 14.02 Notice 17 ARTICLE 15 – SENIORITY & SECURITY 17 15.01 Seniority 17 15.02 Layoffs 18 15.03 Severance Pay 18 15.04 Benefit Continuance 18 15.05 Vacancies 18 ARTICLE 16 – HOURS OF WORK 18 16.01 Work Week 18 16.02 Overtime 18 ARTICLE 17 – CLASSIFICATIONS AND WAGES 19 17.01 Weekly Salaries 19 17.02 Weekly Pay 19 17.03 Experience -

Stations Monitored

Stations Monitored 10/01/2019 Format Call Letters Market Station Name Adult Contemporary WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary WLEV-FM ALLENTOWN-BETHLEHEM, PA 100.7 WLEV Adult Contemporary KMVN-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MOViN 105.7 Adult Contemporary KMXS-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MIX 103.1 Adult Contemporary WOXL-FS ASHEVILLE, NC MIX 96.5 Adult Contemporary WSB-FM ATLANTA, GA B98.5 Adult Contemporary WSTR-FM ATLANTA, GA STAR 94.1 Adult Contemporary WFPG-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ LITE ROCK 96.9 Adult Contemporary WSJO-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ SOJO 104.9 Adult Contemporary KAMX-FM AUSTIN, TX MIX 94.7 Adult Contemporary KBPA-FM AUSTIN, TX 103.5 BOB FM Adult Contemporary KKMJ-FM AUSTIN, TX MAJIC 95.5 Adult Contemporary WLIF-FM BALTIMORE, MD TODAY'S 101.9 Adult Contemporary WQSR-FM BALTIMORE, MD 102.7 JACK FM Adult Contemporary WWMX-FM BALTIMORE, MD MIX 106.5 Adult Contemporary KRVE-FM BATON ROUGE, LA 96.1 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WMJY-FS BILOXI-GULFPORT-PASCAGOULA, MS MAGIC 93.7 Adult Contemporary WMJJ-FM BIRMINGHAM, AL MAGIC 96 Adult Contemporary KCIX-FM BOISE, ID MIX 106 Adult Contemporary KXLT-FM BOISE, ID LITE 107.9 Adult Contemporary WMJX-FM BOSTON, MA MAGIC 106.7 Adult Contemporary WWBX-FM -

A Roadmap to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Call to Action #66

INDIGENOUS YOUTH VOICES A Roadmap to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Call to Action #66 JUNE 2018 INDIGENOUS YOUTH VOICES 1 Kitinanaskimotin / Qujannamiik / Marcee / Miigwech: To all the Indigenous youth and organizations who took the time to share their ideas, experiences, and perspectives with us. To Assembly of Se7en Generations (A7G) who provided Indigenous Youth Voices Advisors administrative and capacity support. ANDRÉ BEAR GABRIELLE FAYANT To the Elders, mentors, friends and family who MAATALII ANERAQ OKALIK supported us on this journey. To the Indigenous Youth Voices team members who Citation contributed greatly to this Roadmap: Indigenous Youth Voices. (2018). A Roadmap to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Call to Action #66. THEA BELANGER MARISSA MILLS Ottawa, Canada Anishinabe/Maliseet Southern Tuschonne/Michif Electronic ISBN Paper ISBN ERIN DONNELLY NATHALIA PIU OKALIK 9781550146585 9781550146592 Haida Inuk LINDSAY DUPRÉ CHARLOTTE QAMANIQ-MASON WEBSITE INSTAGRAM www.indigenousyouthvoices.com @indigenousyouthvoices Michif Inuk FACEBOOK TWITTER WILL LANDON CAITLIN TOLLEY www.fb.com/indigyouthvoices2 A ROADMAP TO TRC@indigyouthvoice #66 Anishinabe Algonquin ACKNOWLEDGMENT We would like to recognize and honour all of the generations of Indigenous youth who have come before us and especially those, who under extreme duress in the Residential School system, did what they could to preserve their language and culture. The voices of Indigenous youth captured throughout this Roadmap echo generations of Indigenous youth before who have spoken out similarly in hopes of a better future for our peoples. Change has not yet happened. We offer this Roadmap to once again, clearly and explicitly show that Indigenous youth are the experts of our own lives, capable of voicing our concerns, understanding our needs and leading change. -

March 8, 2019 S00 County Clerk County of Simcoe Administration

BOX 400 CITY HALL P.O. BARRIE, ONTARIO 70 COLLIER STREET L4M 415 TEL. (705) 792-7900 FAX (705) 739-4265 [email protected] www.barrie.ca THE CORPORATION OF THE CITY OF BARRIE Mayor’s Office March 8, 2019 S00 County Clerk County of Simcoe Administration Centre 1110 Highway 26 Midhurst, Ontario L9X 1N6 Dear County Clerk: As you are no doubt aware, the opioid crisis has hit our City hard. Led by the Simcoe-Muskoka District Health Unit, a broad coalition of public health, law enforcement, social service, and other organizations have come together to combat the crisis within a plan called the Simcoe Muskoka Opioid Strategy (SMOS) focussed on five pillars: Prevention, Treatment, Enforcement, Harm Reduction, and Emergency Management. Although the SMOS is making strides, it is challenged by the need for more resources, specifically financial support and in some cases the need for qualified personnel. As such, and due to the ongoing severity of the crisis, at the Barrie City Council meeting of March 4, 2019, City Council passed the following Resolution concerning the ongoing opioid overdose crisis in Canada: 19-G-049 ONGOING OPIOID OVERDOSE CRISIS IN CANADA WHEREAS Barrie ranks third among large municipalities in Ontario for opioid overdose emergency department (ED) visit rates, and WHEREAS there were 81 opioid-related deaths in Simcoe Muskoka in 2017, with 36 of those deaths in Barrie, and WHEREAS there were an estimated 4000 opioid-related deaths across Canada in 2017, and WHEREAS the central north area of Barrie (which includes downtown) had 10 times the rate of opioid overdose ED visits in 2017 than the provincial average, and four times the overall Barrie average, and WHEREAS the Canadian drug and substances strategy and the Simcoe-Muskoka Opioid Strategy are based on the pillars of Prevention, Treatment, Harm Reduction, Enforcement, and Emergency Management. -

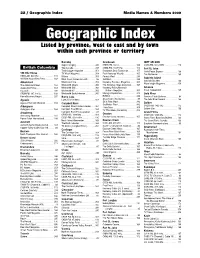

Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by Province, West to East and by Town Within Each Province Or Territory

22 / Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by province, west to east and by town within each province or territory Burnaby Cranbrook fORT nELSON Super Camping . 345 CHDR-FM, 102.9 . 109 CKRX-FM, 102.3 MHz. 113 British Columbia Tow Canada. 349 CHBZ-FM, 104.7mHz. 112 Fort St. John Truck Logger magazine . 351 Cranbrook Daily Townsman. 155 North Peace Express . 168 100 Mile House TV Week Magazine . 354 East Kootenay Weekly . 165 The Northerner . 169 CKBX-AM, 840 kHz . 111 Waters . 358 Forests West. 289 Gabriola Island 100 Mile House Free Press . 169 West Coast Cablevision Ltd.. 86 GolfWest . 293 Gabriola Sounder . 166 WestCoast Line . 359 Kootenay Business Magazine . 305 Abbotsford WaveLength Magazine . 359 The Abbotsford News. 164 Westworld Alberta . 360 The Kootenay News Advertiser. 167 Abbotsford Times . 164 Westworld (BC) . 360 Kootenay Rocky Mountain Gibsons Cascade . 235 Westworld BC . 360 Visitor’s Magazine . 305 Coast Independent . 165 CFSR-FM, 107.1 mHz . 108 Westworld Saskatchewan. 360 Mining & Exploration . 313 Gold River Home Business Report . 297 Burns Lake RVWest . 338 Conuma Cable Systems . 84 Agassiz Lakes District News. 167 Shaw Cable (Cranbrook) . 85 The Gold River Record . 166 Agassiz/Harrison Observer . 164 Ski & Ride West . 342 Golden Campbell River SnoRiders West . 342 Aldergrove Campbell River Courier-Islander . 164 CKGR-AM, 1400 kHz . 112 Transitions . 350 Golden Star . 166 Aldergrove Star. 164 Campbell River Mirror . 164 TV This Week (Cranbrook) . 352 Armstrong Campbell River TV Association . 83 Grand Forks CFWB-AM, 1490 kHz . 109 Creston CKGF-AM, 1340 kHz. 112 Armstrong Advertiser . 164 Creston Valley Advance. -

Leadership by Design to Unveil One Place to Look, OLBA's On-Line

For and about members of the ONTARIO LIBRARY BOARDS’ ASSOCIATION InsideOLBA WINTER 2008 NO. 21 ISSN 1192 5167 Leadership by Design to unveil One Place to Look, OLBA’s on-line library for trustees he Ontario Library everything easier to use. One Boards‘Association is Place to Look is the result of ready to unveil the latest research done by Margaret component of its four-year pro- Andrewes and Randee Loucks gram, Leadership by Design. in which trustees said they TThe project’s on-line library wanted to look for resources in for trustees, One Place to Look, one place and that the search is ready for launch at the 2008 needed to be as simple as possi- Super Conference. OLBA ble. Council has seen the test ver- Many trustees with little on- sion and were thrilled with line experience were particular- what they saw. You will be, too. ly anxious that access to trustee materials be simple. These One Place to Look builds findings informed the develop- on Cut to the Chase ment of One Place to Look, our Cut to the Chase is the on-line library for trustees. durable, laminated four-page fold-out quick reference guide Your Path to Library to being a trustee. This was the Leadership is the Key damental responsibilities in years by the Library Develop- first element in the Leadership Borrowing the name from achieving effective leadership ment Training Program spear- by Design project. Since the the Ontario library communi- and sound library governance. headed by the Southern Ontario final version of Cut to the ty’s 1990 Strategic Plan that The “Your Path to Library Library Service in combination Chase was delivered to all saw the beginning of more Leadership ” chart on the back with the Ontario Library library boards in Ontario, the intensive focus on board devel- of Cut to the Chase is your key Service-North and the Ontario response has been excellent. -

Canada 2020 International Religious Freedom Report

CANADA 2020 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The constitution guarantees freedom of conscience, religion, thought, belief, opinion, expression, and the right to equal protection and benefit of the law without discrimination based on religion. The government does not require religious groups to register, but some registered groups may receive tax-exempt status. In November, the Quebec Court of Appeal reduced the sentence of a man to 25 years before eligibility for parole after he pled guilty in 2018 to six counts of first-degree murder for the 2017 killing of six worshippers at the Islamic Cultural Centre of Quebec. In November and December, a Quebec court concurrently heard challenges by four groups of plaintiffs, including the National Council of Canadian Muslims, Canadian Civil Liberties Association, the English Montreal School Board, a Quebec teachers union, and individuals to strike down as unconstitutional a provincial law prohibiting certain categories of government employees from wearing religious symbols while exercising their official functions. The law remained in force through year’s end. Provincial governments imposed societal restrictions on assembly, including for all faith groups, to limit the transmission of COVID-19, but some religious communities said provincial orders and additional measures were discriminatory. Quebec authorities imposed a temporary mandatory COVID-19 quarantine on a Hasidic Jewish community in a suburb of Montreal that some members said was discriminatory because it applied only to Jews, although the religious community had initiated the quarantine voluntarily. Some members of Hutterite colonies in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta said they experienced societal discrimination outside their communities due to provincial governments publishing outbreaks of COVID-19 in Hutterite communities. -

Fisher Auditorium

and pathway. Crews are now finishing up the new permanent basketball court/ice rink. The rink is expected to open by the 2017 Highlights end of the year. Keep an eye on the City’s website for the latest (barrie.ca). Recycled Road Sand Pilot Program Saving City $500,000 Annually New Recreation Centre and Library The City of Barrie will be saving half a million dollars this year Coming to Ward 10 by collecting and recycling road sand as part of winter control. On November 20, 2017, Barrie City Council approved location, The sand that is collected from roads during the annual spring programs and facility concepts for a new Recreation Centre street sweeping program has typically been disposed of at the and Library in Ward 10. The proposed location is on the west landfill. This City put down 7,400 tonnes of sand on City streets side of Yonge Street, north of Lockhart Road. The approximate last winter and collected 4,137 tonnes during street sweeping in 18 acres of land is currently used as farmland. The concept the spring. 87% of that sand was diverted from the landfill thanks includes: 2 ice pads 42,414 sf pool 20,920 square foot – to this new innovative program. fitness centre 26,617 square foot - gymnasium 15,392 square foot - library Outdoor splash pad Soccer field Emergency Services Campus 3 tennis and pickle ball courts Playground and skate park. The City is embarking on an innovative facility that will house Barrie Police, Simcoe County Paramedics and Barrie Fire Why I LOVE Barrie Emergency Service dispatch communications in one location, Last year I ran my first ‘Why I love Barrie’ contest and the response at 110 Fairview Road. -

City Council Meeting No.15, June 18, 2002

CITY COUNCIL MEETING NO. 15-2002 The Regular Meeting of City Council was held on Tuesday, June 18, 2002 at 7:30 p.m. in the Council Chamber, City Hall. Her Worship Mayor Isabel Turner presided. There was an "In-Camera" meeting of the Committee of the Whole from 6:30 pm to 7:30 pm in the Councillors’ Lounge. (Council Chambers) ROLL CALL Present: Mayor Turner, Councillor Beavis, Councillor Campbell, Councillor Clements, Councillor Downes, Councillor Foster, Councillor Garrison (arrived 8:15 pm), Councillor George, Councillor Pater, Councillor Rogers, Councillor Stoparczyk, Councillor Sutherland. (12) Absent: Councillor Meers (1) (Council Chambers) Administrative Staff Present: Mr. B. Meunier, CAO; Ms. C. Beach, Commissioner, Planning & Development Services; Mrs. C. Downs, Manager, Council Support/City Clerk; Mr. M. Fluhrer, Manager, Parks & Arenas Division; Mr. D. Leger, Commissioner, Corporate Services; Mr. H. Linscott, Director, Legal Services; Mr. P. MacLatchy, Manager, Environmental Services; Ms. N. Sullivan, Deputy City Clerk. * * * * * * * * * * * * COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE “IN CAMERA” (A) Moved by Councillor Pater Seconded by Councillor Rogers THAT Council resolve itself into the Committee of the Whole “In Camera” to consider the following items: 1. Litigation or Potential Litigation 2. Negotiations 3. Legal Matters CARRIED * * * * * * * * * * * * City Council Meeting No. 15 Minutes June 18, 2002 Page 398 (Council Chambers) Administrative Staff Present: Mr. B. Meunier, CAO; Ms. C. Beach, Commissioner, Planning & Development Services; Mr. B. Bishop, Director, Human Resources; Mr. J. Cross, Community Development Facilitator, Emergency Management; Mrs. C. Downs, Manager, Council Support/City Clerk; Mr. M. Fluhrer, Manger, Parks & Arenas; Mr. G. Grange, Manager, Social Housing Division; Mr. G. -

Core 1..160 Hansard (PRISM::Advent3b2 16.00)

House of Commons Debates VOLUME 147 Ï NUMBER 010 Ï 2nd SESSION Ï 41st PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Tuesday, October 29, 2013 Speaker: The Honourable Andrew Scheer CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) 507 HOUSE OF COMMONS Tuesday, October 29, 2013 The House met at 10 a.m. that the House immediately adopt the provisions of private member's Motion No. 461, listed on today's Order Paper, that deals specifically with the creation of a special committee of this House on security and intelligence oversight, to be appointed to study and make Prayers recommendations with respect to the appropriate method of parliamentary oversight of Canadian government policies, regula- tions and activities in the areas of intelligence, including all of those ROUTINE PROCEEDINGS departments, agencies and review bodies, civilian and military, involved in the collection, analysis and dissemination of intelligence Ï (1005) for the purpose of Canada's national security. [English] The Speaker: Does the hon. member for St. John's East have the PRIVACY COMMISSIONER unanimous consent of the House? The Speaker: I have the honour to lay upon the table the annual Some hon. members: No. report on the Privacy Act of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada for the year 2012-13. *** [Translation] PETITIONS This document is deemed to have been permanently referred to the HUMAN RIGHTS Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights. Mrs. Joy Smith (Kildonan—St. Paul, CPC): Mr. Speaker, I have several hundred petitioners among my constituents in *** Winnipeg, Manitoba. They call upon the House of Commons to [English] ensure that the Holodomor and Canada's first national internment FIRST NATIONS ELECTIONS ACT operations are permanently and prominently displayed at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights in its galleries. -

B. Background of Molson Inc

Bibliothèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence dowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfom, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/fïlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. CHAPTER ONE: SETTING AND CONTEXT OF STUDY A. Introduction Molson Inc. ("Molson") has been in the brewery business since 1786, representing one of Canada's oldest consumer brands. Ending a period of diverse corporate holdings, 1998 saw the retum of the organization to its core business following the sale of other unrelated holdings, The Molson 1999 Annual Report (fiscal year endhg March 3 1, 1999) boasts 3,850 ernployees and seven brewexies across Canada, including the subject of this paper, the Molson plant located in Barrie, Ontario, approximately 100 kilometers north of Toronto ("Molson B amie"). The 1990s were for Molson a time of continuous corporate change and restructuring dnven by the necessity to meet the pressures of a world economy that was rapidly changing on cornpetitive, regulatory and technical fronts.