The Chronology of Perpendicular Architecture in Oxford

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pevsner's Architectural Glossary

Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 1 PEVSNER’S ARCHITECTURAL GLOSSARY Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 2 Nikolaus and Lola Pevsner, Hampton Court, in the gardens by Wren's east front, probably c. Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 3 PEVSNER’S ARCHITECTURAL GLOSSARY Yale University Press New Haven and London Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 4 Temple Street, New Haven Bedford Square, London www.pevsner.co.uk www.lookingatbuildings.org.uk www.yalebooks.co.uk www.yalebooks.com for Published by Yale University Press Copyright © Yale University, Printed by T.J. International, Padstow Set in Monotype Plantin All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections and of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 5 CONTENTS GLOSSARY Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 6 FOREWORD The first volumes of Nikolaus Pevsner’s Buildings of England series appeared in .The intention was to make available, county by county, a comprehensive guide to the notable architecture of every period from prehistory to the present day. Building types, details and other features that would not necessarily be familiar to the general reader were explained in a compact glossary, which in the first editions extended to some terms. -

11 Witney - Hanborough - Oxford

11 Witney - Hanborough - Oxford Mondays to Saturdays notes M-F M-F S M-F M-F Witney Market Square stop C 06.14 06.45 07.45 - 09.10 10.10 11.15 12.15 13.15 14.15 15.15 16.20 - Madley Park Co-op 06.21 06.52 07.52 - - North Leigh Masons Arms 06.27 06.58 07.58 - 09.18 10.18 11.23 12.23 13.23 14.23 15.23 16.28 17.30 Freeland Broadmarsh Lane 06.35 07.06 08.07 07.52 09.27 10.27 11.32 12.32 13.32 14.32 15.32 16.37 17.40 Long Hanborough New Road 06.40 07.11 08.11 07.57 09.31 10.31 11.36 12.36 13.36 14.36 15.36 16.41 Eynsham Spareacre Lane 06.49 07.21 08.20 09.40 10.40 11.45 12.45 13.45 14.45 15.45 16.50 Eynsham Church 06.53 07.26 08.24 08.11 09.44 10.44 11.49 12.49 13.49 14.49 15.49 16.54 17.49 Botley Elms Parade 07.06 07.42 08.33 08.27 09.53 10.53 11.58 12.58 13.58 14.58 15.58 17.03 18.00 Oxford Castle Street 07.21 08.05 08.47 08.55 10.07 11.07 12.12 13.12 13.12 15.12 16.12 17.17 18.13 notes M-F M-F S M-F M-F S Oxford Castle Street E2 07.25 08.10 09.10 10.15 11.15 12.15 13.15 14.15 15.15 16.35 16.35 17.35 17.50 Botley Elms Parade 07.34 08.20 09.20 10.25 11.25 12.25 13.25 14.25 15.25 16.45 16.50 17.50 18.00 Eynsham Church 07.43 08.30 09.30 10.35 11.35 12.35 13.35 14.35 15.35 16.55 17.00 18.02 18.10 Eynsham Spareacre Lane 09.34 10.39 11.39 12.39 13.39 14.39 15.39 16.59 17.04 18.06 18.14 Long Hanborough New Road 09.42 10.47 11.47 12.47 13.47 14.47 15.47 17.07 17.12 18.14 18.22 Freeland Broadmarsh Lane 07.51 08.38 09.46 10.51 11.51 12.51 13.51 14.51 15.51 17.11 17.16 18.18 18.26 North Leigh Masons Arms - 08.45 09.55 11.00 12.00 13.00 -

Gothic Beyond Architecture: Manchester’S Collegiate Church

Gothic beyond Architecture: Manchester’s Collegiate Church My previous posts for Visit Manchester have concentrated exclusively upon buildings. In the medieval period—the time when the Gothic style developed in buildings such as the basilica of Saint-Denis on the outskirts of Paris, Île-de-France (Figs 1–2), under the direction of Abbot Suger (1081–1151)—the style was known as either simply ‘new’, or opus francigenum (literally translates as ‘French work’). The style became known as Gothic in the sixteenth century because certain high-profile figures in the Italian Renaissance railed against the architecture and connected what they perceived to be its crude forms with the Goths that sacked Rome and ‘destroyed’ Classical architecture. During the nineteenth century, critics applied Gothic to more than architecture; they located all types of art under the Gothic label. This broad application of the term wasn’t especially helpful and it is no-longer used. Gothic design, nevertheless, was applied to more than architecture in the medieval period. Applied arts, such as furniture and metalwork, were influenced by, and followed and incorporated the decorative and ornament aspects of Gothic architecture. This post assesses the range of influences that Gothic had upon furniture, in particular by exploring Manchester Cathedral’s woodwork, some of which are the most important examples of surviving medieval woodwork in the North of England. Manchester Cathedral, formerly the Collegiate Church of the City (Fig.3), see here, was ascribed Cathedral status in 1847, and it is grade I listed (Historic England listing number 1218041, see here). It is medieval in foundation, with parts dating to between c.1422 and 1520, however it was restored and rebuilt numerous times in the nineteenth century, and it was notably hit by a shell during WWII; the shell failed to explode. -

The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: the Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry Versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry

Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture Volume 5 Issue 2 135-172 2015 The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry Nelly Shafik Ramzy Sinai University Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Ramzy, Nelly Shafik. "The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry." Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture 5, 2 (2015): 135-172. https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal/vol5/iss2/7 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art History at Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture by an authorized editor of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ramzy The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry By Nelly Shafik Ramzy, Department of Architectural Engineering, Faculty of Engineering Sciences, Sinai University, El Masaeed, El Arish City, Egypt 1. Introduction When performing geometrical analysis of historical buildings, it is important to keep in mind what were the intentions -

The Digital Nature of Gothic

The Digital Nature of Gothic Lars Spuybroek Ruskin’s The Nature of Gothic is inarguably the best-known book on Gothic architecture ever published; argumentative, persuasive, passionate, it’s a text influential enough to have empowered a whole movement, which Ruskin distanced himself from on more than one occasion. Strangely enough, given that the chapter we are speaking of is the most important in the second volume of The Stones of Venice, it has nothing to do with the Venetian Gothic at all. Rather, it discusses a northern Gothic with which Ruskin himself had an ambiguous relationship all his life, sometimes calling it the noblest form of Gothic, sometimes the lowest, depending on which detail, transept or portal he was looking at. These are some of the reasons why this chapter has so often been published separately in book form, becoming a mini-bible for all true believers, among them William Morris, who wrote the introduction for the book when he published it First Page of John Ruskin’s “The with his own Kelmscott Press. It is a precious little book, made with so much love and Nature of Gothic: a chapter of The Stones of Venice” (Kelmscott care that one hardly dares read it. Press, 1892). Like its theoretical number-one enemy, classicism, the Gothic has protagonists who write like partisans in an especially ferocious army. They are not your usual historians – the Gothic hasn’t been able to attract a significant number of the best historians; it has no Gombrich, Wölfflin or Wittkower, nobody of such caliber – but a series of hybrid and atypical historians such as Pugin and Worringer who have tried again and again, like Ruskin, to create a Gothic for the present, in whatever form: revivalist, expressionist, or, as in my case, digitalist, if that is a word. -

Pick of the Churches

Pick of the Churches The East of England is famous for its superb collection of churches. They are one of the nation's great treasures. Introduction There are hundreds of churches in the region. Every village has one, some villages have two, and sometimes a lonely church in a field is the only indication that a village existed there at all. Many of these churches have foundations going right back to the dawn of Christianity, during the four centuries of Roman occupation from AD43. Each would claim to be the best - and indeed, all have one or many splendid and redeeming features, from ornate gilt encrusted screens to an ancient font. The history of England is accurately reflected in our churches - if only as a tantalising glimpse of the really creative years between the 1100's to the 1400's. From these years, come the four great features which are particularly associated with the region. - Round Towers - unique and distinctive, they evolved in the 11th C. due to the lack and supply of large local building stone. - Hammerbeam Roofs - wide, brave and ornate, and sometimes strewn with angels. Just lay on the floor and look up! - Flint Flushwork - beautiful patterns made by splitting flints to expose a hard, shiny surface, and then setting them in the wall. Often it is used to decorate towers, porches and parapets. - Seven Sacrament Fonts - ancient and splendid, with each panel illustrating in turn Baptism, Confirmation, Mass, Penance, Extreme Unction, Ordination and Matrimony. Bedfordshire Ampthill - tomb of Richard Nicholls (first governor of Long Island USA), including cannonball which killed him. -

Applications Determined Under Delegated Powers PDF 317 KB

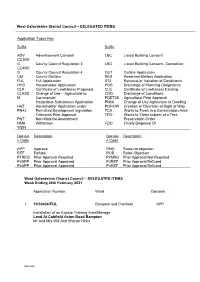

West Oxfordshire District Council – DELEGATED ITEMS Application Types Key Suffix Suffix ADV Advertisement Consent LBC Listed Building Consent CC3RE G County Council Regulation 3 LBD Listed Building Consent - Demolition CC4RE G County Council Regulation 4 OUT Outline Application CM County Matters RES Reserved Matters Application FUL Full Application S73 Removal or Variation of Condition/s HHD Householder Application POB Discharge of Planning Obligation/s CLP Certificate of Lawfulness Proposed CLE Certificate of Lawfulness Existing CLASS Change of Use – Agriculture to CND Discharge of Conditions M Commercial PDET28 Agricultural Prior Approval Hazardous Substances Application PN56 Change of Use Agriculture to Dwelling HAZ Householder Application under POROW Creation or Diversion of Right of Way PN42 Permitted Development legislation. TCA Works to Trees in a Conservation Area Telecoms Prior Approval TPO Works to Trees subject of a Tree PNT Non Material Amendment Preservation Order NMA Withdrawn FDO Finally Disposed Of WDN Decisio Description Decisio Description n Code n Code APP Approve RNO Raise no objection REF Refuse ROB Raise Objection P1REQ Prior Approval Required P2NRQ Prior Approval Not Required P3APP Prior Approval Approved P3REF Prior Approval Refused P4APP Prior Approval Approved P4REF Prior Approval Refused West Oxfordshire District Council – DELEGATED ITEMS Week Ending 26th February 2021 Application Number. Ward. Decision. 1. 19/03436/FUL Bampton and Clanfield APP Installation of an Equine Training Area/Manege Land At Cobfield Aston Road Bampton Mr And Mrs Will And Sharon Hicks DELGAT 2. 20/01655/FUL Ducklington REF Erection of four new dwellings and associated works (AMENDED PLANS) Land West Of Glebe Cottage Lew Road Curbridge Mr W Povey, Mr And Mrs C And J Mitchel And Abbeymill Homes L 3. -

The English Claim to Gothic: Contemporary Approaches to an Age-Old Debate (Under the Direction of DR STEFAAN VAN LIEFFERINGE)

ABSTRACT MARY ELIZABETH BLUME The English Claim to Gothic: Contemporary Approaches to an Age-Old Debate (Under the Direction of DR STEFAAN VAN LIEFFERINGE) The Gothic Revival of the nineteenth century in Europe aroused a debate concerning the origin of a style already six centuries old. Besides the underlying quandary of how to define or identify “Gothic” structures, the Victorian revivalists fought vehemently over the national birthright of the style. Although Gothic has been traditionally acknowledged as having French origins, English revivalists insisted on the autonomy of English Gothic as a distinct and independent style of architecture in origin and development. Surprisingly, nearly two centuries later, the debate over Gothic’s nationality persists, though the nationalistic tug-of-war has given way to the more scholarly contest to uncover the style’s authentic origins. Traditionally, scholarship took structural or formal approaches, which struggled to classify structures into rigidly defined periods of formal development. As the Gothic style did not develop in such a cleanly linear fashion, this practice of retrospective labeling took a second place to cultural approaches that consider the Gothic style as a material manifestation of an overarching conscious Gothic cultural movement. Nevertheless, scholars still frequently look to the Isle-de-France when discussing Gothic’s formal and cultural beginnings. Gothic historians have entered a period of reflection upon the field’s historiography, questioning methodological paradigms. This -

Programme of Events

Programme www.alumniweekend.ox.ac.uk of events Alumni Weekend in Oxford 19–21 September 2014 How to book 1 Browse the brochure and use the handy pull-out planner to help decide which sessions to attend. You can now search for programme content by college and subject division (see pp37–47). 2 Book online at www.alumniweekend.ox.ac.uk OR complete the booking form and return it by Friday 12 September. We recommend that you book early, as some sessions sell out quickly. 3 We’ll send you a booking confirmation as soon as your registration has been processed. Final event details will be sent in early September. Booking opens: 7 July 2014 Booking closes: 12 September 2014 Cover art inspired by the Penrose Paving at the Maths Institute Rob Judges/Oxford University Images Welcome Contents Booking your place 2 Now in its eighth year, our annual Meeting Our main venue this year will be the recently- Minds event continues to showcase the best opened Mathematical Institute – the Andrew Friday 19 September 5 and brightest of Oxford – past, present and Wiles Building - on the Radcliffe Observatory Saturday 20 September 13 future. Quarter off Woodstock Road and within easy reach of the city centre and most colleges. Sunday 21 September 29 All of our Meeting Minds events (and you The building’s design demonstrates how can now enjoy these occasions in Asia, Europe Family-friendly events 35 mathematical ideas are part of everyday life and North America as well as in Oxford) shine from the paving, featuring patterns dreamt up Colleges 37 a spotlight on the real-world impact of University by Oxford mathematician Sir Roger Penrose research, through a programme of lectures Subjects 45 (one of our featured speakers), to the crystal- and panel discussions. -

Fan Vaults After the English Gothic

Gloucester Cathedral cloister walk, slideshare.net/michae FAN lasanda/gloucester- cathedral2 VAULTS King’s College Chapel, quora.com/Are-there-any- buildings-with-fanned-vaulting-outside-of-the-US- Bath Abbey, quillcards.com/blog/bath-abbey/ UK-and-Canada Citation: K. Bagi (2018): Mechanics of Masonry Structures. Course handouts, Department of Structural Mechanics, Budapest University of Technology and Economics The images in this file may be subjected to copyright. In case of any question or problem, do not hesitate to contact Prof. K. Bagi, [email protected] . THIS LECTURE Definition Preliminaries to fan vaulting Reminder on the membrane solution Beginning of fan vaulting Constructional issues jointed masonry versus rib-and-panel system pendants roofing variations to the groundplan variations to the spandrel geometry the generator curve geometry Decline of fan vaulting; Fan vaults after the English Gothic Questions 2 / 43 DEFINITION When: Late Gothic; between the middle of XIVth – middle of XVIth century Where: in England only! (?? baltic examples ??) Definition: The shell is a surface of revolution: a smooth arc, concave from below, is rotated about a vertical axis being on the outer side. Bath Abbey, Vertical main ribs have identical shape, devizesdays.blogspot.com/2013/11/st-andrews- and are arranged at equal angles. school-sings-in-bath-abbey.html Between the conoids, a distinct spandrel panel is placed. The ribs are perpendicular to the surface. 3 / 43 DEFINITION Main components: + often applied: upfill in the vaulting -

Excavations at Vicarage Field, Stanton Harcourt, 1951

Excavations at Vicarage Field, Stanton Harcourt, 1951 WITH AN ApPENDIX ON SECONDARY NEOLITmC WARES IN THE OXFORD REGION By NICHOLAS THOMAS THE SITE ICARAGE Field (FIG. I) lies less than half a mile from the centre of V Stanton Harcourt village, on the road westward to Beard Mill. It is situated on one of the gravel terraces of the upper Thames. A little to the west the river Windrush flows gently southwards to meet the Thames below Standlake. About four miles north-east another tributary, the Evenlode, runs into the Thames wlllch itself curves north, about Northmoor, past Stanton Harcourt and Eynsham to meet it. The land between this loop of the Thames and the smaller channels of the Windrush and Evenlode is flat and low-lying; but the gravel subsoil allows excellent drainage so that in early times, whatever their culture or occupation, people were encouraged to settle there.' Vicarage Field and the triangular field south of the road from Stanton Harcourt to Beard Mill enclose a large group of sites of different periods. The latter field was destroyed in 1944-45, after Mr. D. N. Riley had examined the larger ring-ditch in it and Mr. R. J. C. Atkinson the smaller.' Gravel-working also began in Vicarage Field in 1944, at which time Mrs. A. Williams was able to examine part of the area that was threatened. During September, 1951,' it became necessary to restart excavations in Vicarage Field when the gravel-pit of Messrs. Ivor Partridge & Sons (Beg broke) Ltd. was suddenly extended westward, involving a further two acres of ground. -

College and Research Libraries

By MAX LEDERE~ A Stroll Through English Libraries Dr. Lederer is a fellow of the Library of now, a modern library having been estab Congress. lished right below the old one. The Bod leian Library, however, is still, as it has been HEN VISITING English libraries, one for ages, a working library, not only one of W looks back to six centuries of devoted the most revered, but also one of the largest service to the reader. Within convenient and most important institutions of its kind. range of the traveler are London and Ox The old Bodleian is too well known to ford. The libraries of these two cities offer require a minute description. Generation a good choice for a general view. after generation has climbed the shallow Let us start with Oxford, the ancient seat steps of the quaint wooden staircase. One of learning fQr almost seven centuries, would not suspect when passing the modest whose coat of arms humbly points to the entrance in a corner of the Old Schools eternal source of all truth and wisdom: Quadrangle that he was entering one of the Dominus illuminatio mea. In the venerable noblest repositories of man's wisdom and Merton College Library-the building was learning. Founded in the fifteenth century erected in the years I373-78-the lance it was despoiled IOO years later, and then shaped, narrow windows throw a dim light restored by Sir Thomas Bodley at the end on rows of leather-bound volumes, the gilt of the sixteenth century. The !-square titles and edges of which have long ago shaped hall with its beautiful old roofing, faded.