Discussion Papers in Economic and Social History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Subject Guide 1 – Records Relating to Inclosure

Durham County Record Office County Hall Durham DH1 5UL Telephone: 03000 267619 Email: [email protected] Website: www.durhamrecordoffice.org.uk Subject Guide 1 – Records Relating to Inclosure Issue no. 19 July 2020 Contents Introduction 1 Organisation of List 2 Alphabetical List of Townships 2 A 2 B 2 C 3 D 4 E 4 F 4 G 4 H 5 I 5 K 5 L 5 M 6 N 6 O 6 R 6 S 7 T 7 U 8 W 8 Introduction Inclosure (occasionally spelled “enclosure”) refers to a reorganisation of scattered land holdings by mutual agreement of the owners. Much inclosure of Common Land, Open Fields and Moor Land (or Waste), formerly farmed collectively by the residents on behalf of the Lord of the Manor, had taken place by the 18th century, but the uplands of County Durham remained largely unenclosed. Inclosures, to consolidate land-holdings, divide the land (into Allotments) and fence it off from other usage, could be made under a Private Act of Parliament or by general agreement of the landowners concerned. In the latter case the Agreement would be Enrolled as a Decree at the Court of Chancery in Durham and/or lodged with the Clerk of the Peace, the senior government officer in the County, so may be preserved in Quarter Sessions records. In the case of Parliamentary Enclosure a Local Bill would be put before Parliament which would pass it into law as an Inclosure Act. The Acts appointed Commissioners to survey the area concerned and determine its distribution as a published Inclosure Award. -

11 Witney - Hanborough - Oxford

11 Witney - Hanborough - Oxford Mondays to Saturdays notes M-F M-F S M-F M-F Witney Market Square stop C 06.14 06.45 07.45 - 09.10 10.10 11.15 12.15 13.15 14.15 15.15 16.20 - Madley Park Co-op 06.21 06.52 07.52 - - North Leigh Masons Arms 06.27 06.58 07.58 - 09.18 10.18 11.23 12.23 13.23 14.23 15.23 16.28 17.30 Freeland Broadmarsh Lane 06.35 07.06 08.07 07.52 09.27 10.27 11.32 12.32 13.32 14.32 15.32 16.37 17.40 Long Hanborough New Road 06.40 07.11 08.11 07.57 09.31 10.31 11.36 12.36 13.36 14.36 15.36 16.41 Eynsham Spareacre Lane 06.49 07.21 08.20 09.40 10.40 11.45 12.45 13.45 14.45 15.45 16.50 Eynsham Church 06.53 07.26 08.24 08.11 09.44 10.44 11.49 12.49 13.49 14.49 15.49 16.54 17.49 Botley Elms Parade 07.06 07.42 08.33 08.27 09.53 10.53 11.58 12.58 13.58 14.58 15.58 17.03 18.00 Oxford Castle Street 07.21 08.05 08.47 08.55 10.07 11.07 12.12 13.12 13.12 15.12 16.12 17.17 18.13 notes M-F M-F S M-F M-F S Oxford Castle Street E2 07.25 08.10 09.10 10.15 11.15 12.15 13.15 14.15 15.15 16.35 16.35 17.35 17.50 Botley Elms Parade 07.34 08.20 09.20 10.25 11.25 12.25 13.25 14.25 15.25 16.45 16.50 17.50 18.00 Eynsham Church 07.43 08.30 09.30 10.35 11.35 12.35 13.35 14.35 15.35 16.55 17.00 18.02 18.10 Eynsham Spareacre Lane 09.34 10.39 11.39 12.39 13.39 14.39 15.39 16.59 17.04 18.06 18.14 Long Hanborough New Road 09.42 10.47 11.47 12.47 13.47 14.47 15.47 17.07 17.12 18.14 18.22 Freeland Broadmarsh Lane 07.51 08.38 09.46 10.51 11.51 12.51 13.51 14.51 15.51 17.11 17.16 18.18 18.26 North Leigh Masons Arms - 08.45 09.55 11.00 12.00 13.00 -

The Bungalow Windrush Valley, Oxfordshire the Bungalow

The Bungalow Windrush Valley, Oxfordshire The Bungalow WINDRUSH VALLEY • OXFORDSHIRE An exclusive opportunity to build your own country house set in an area of outstanding natural beauty amongst rolling Cotswold countryside in the Windrush Valley near Swinbrook and Burford. Existing Bungalow Dining room | Sitting room | Kitchen Three Bedrooms | One bathroom Double garage | Peaceful location Plenty of parking Planning Permission There is planning permission for a contemporary Architect designed 6 en-suite bedroom family house replacement dwelling of up to 3,700 sq ft above ground using the existing access. In all about 3.45 acres Asthall 1 mile, Swinbrook 2 miles, Burford 4 miles, Witney 4 miles, Charlbury (trains to London Paddington 76 minutes) 9 miles, Oxford 18 miles (trains to London Marylebone 56 minutes) (all distances are approximate). These particulars are intended only as a guide and must not be relied upon as statements of fact. Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the text. glazed stairwell glazed stairwell MASTER BEDROOM rooflights to light ensuite bathroom MASTER BEDROOM rooflights to light ensuite bathroom glazed stairwell A - Floor area increased, layout altered MASTER BEDROOM BEDROOM 5 following client comments - March 2020 ENSUITE rooflights to light ensuite bathroom CUP'D A - Floor area increased, layout altered ENSUITE BEDROOM 5 following client comments - March 2020 ENSUITE CUP'D DRESSING ENSUITE ENSUITE DRESSING BEDROOM 3 ENSUITE A - Floor area increased, layout altered CUP'D BEDROOM -

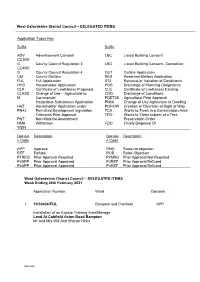

Applications Determined Under Delegated Powers PDF 317 KB

West Oxfordshire District Council – DELEGATED ITEMS Application Types Key Suffix Suffix ADV Advertisement Consent LBC Listed Building Consent CC3RE G County Council Regulation 3 LBD Listed Building Consent - Demolition CC4RE G County Council Regulation 4 OUT Outline Application CM County Matters RES Reserved Matters Application FUL Full Application S73 Removal or Variation of Condition/s HHD Householder Application POB Discharge of Planning Obligation/s CLP Certificate of Lawfulness Proposed CLE Certificate of Lawfulness Existing CLASS Change of Use – Agriculture to CND Discharge of Conditions M Commercial PDET28 Agricultural Prior Approval Hazardous Substances Application PN56 Change of Use Agriculture to Dwelling HAZ Householder Application under POROW Creation or Diversion of Right of Way PN42 Permitted Development legislation. TCA Works to Trees in a Conservation Area Telecoms Prior Approval TPO Works to Trees subject of a Tree PNT Non Material Amendment Preservation Order NMA Withdrawn FDO Finally Disposed Of WDN Decisio Description Decisio Description n Code n Code APP Approve RNO Raise no objection REF Refuse ROB Raise Objection P1REQ Prior Approval Required P2NRQ Prior Approval Not Required P3APP Prior Approval Approved P3REF Prior Approval Refused P4APP Prior Approval Approved P4REF Prior Approval Refused West Oxfordshire District Council – DELEGATED ITEMS Week Ending 26th February 2021 Application Number. Ward. Decision. 1. 19/03436/FUL Bampton and Clanfield APP Installation of an Equine Training Area/Manege Land At Cobfield Aston Road Bampton Mr And Mrs Will And Sharon Hicks DELGAT 2. 20/01655/FUL Ducklington REF Erection of four new dwellings and associated works (AMENDED PLANS) Land West Of Glebe Cottage Lew Road Curbridge Mr W Povey, Mr And Mrs C And J Mitchel And Abbeymill Homes L 3. -

Nov 12.Qxp:Feb 08.Qxd

Issue 352 November 2012 50p HGV ban Fun at the Autumn Fair County Cabinet forced to reinstate plan to deal with Chippy’s illegal pollution levels A plan to ‘downgrade’ the A44 and force a lorry weight restriction through Chipping Norton’s town centre is back in Oxfordshire’s Transport plan – but only after a row and a Cabinet u-turn. Air pollution in the Horsefair hotspot was A sunny Saturday in October saw the town declared illegal back in 2006. After 10 years of centre buzzing with people enjoying appraisals, options and the famous ‘black box’ on Transition Chipping Norton’s Autumn Fair. Topside, Oxfordshire County Council officially Fancy dress winner Chace Jones (right) is announced the ‘plan for a ban’ in their 2011 Local pictured with other entrants and TCN’s Transpor t plan. Barbara Saunders. Report and more Hopes were then dashed – first ‘funding cuts’ pictures on page 7. were blamed, then in April this year the County Cabinet tried to withdraw the whole idea. Chippy’s County Councillor Hilary Biles objected Maternity unit at full Council and now Cllr Rodney Rose, the Cabinet member who runs the roads, has reinstated the plan after a ‘scrutiny’ review. closure shock So it still could happen – but when and how? It Chipping Norton’s brand new will be up to local people, councillors and maternity unit, opened by MP David WODC to keep pressure on the County and work with other affected towns. Full story on Cameron last year, has closed for a this extraordinary turn of events inside. -

Postal Sector Council Alternative Sector Name Month (Dates)

POSTAL COUNCIL ALTERNATIVE SECTOR NAME MONTH (DATES) SECTOR BN15 0 Adur District Council Sompting, Coombes 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN15 8 Adur District Council Lancing (Incl Sompting (South)) 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN15 9 Adur District Council Lancing (Incl Sompting (North)) 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN42 4 Adur District Council Southwick 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN43 5 Adur District Council Old Shoreham, Shoreham 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN43 6 Adur District Council Kingston By Sea, Shoreham-by-sea 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN12 5 Arun District Council Ferring, Goring-by-sea 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN16 1 Arun District Council East Preston 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN16 2 Arun District Council Rustington (South), Brighton 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN16 3 Arun District Council Rustington, Brighton 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN16 4 Arun District Council Angmering 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN17 5 Arun District Council Littlehampton (Incl Climping) 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN17 6 Arun District Council Littlehampton (Incl Wick) 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN17 7 Arun District Council Wick, Lyminster 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN18 0 Arun District Council Yapton, Walberton, Ford, Fontwell 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN18 9 Arun District Council Arundel (Incl Amberley, Poling, Warningcamp) -

Excavations at Vicarage Field, Stanton Harcourt, 1951

Excavations at Vicarage Field, Stanton Harcourt, 1951 WITH AN ApPENDIX ON SECONDARY NEOLITmC WARES IN THE OXFORD REGION By NICHOLAS THOMAS THE SITE ICARAGE Field (FIG. I) lies less than half a mile from the centre of V Stanton Harcourt village, on the road westward to Beard Mill. It is situated on one of the gravel terraces of the upper Thames. A little to the west the river Windrush flows gently southwards to meet the Thames below Standlake. About four miles north-east another tributary, the Evenlode, runs into the Thames wlllch itself curves north, about Northmoor, past Stanton Harcourt and Eynsham to meet it. The land between this loop of the Thames and the smaller channels of the Windrush and Evenlode is flat and low-lying; but the gravel subsoil allows excellent drainage so that in early times, whatever their culture or occupation, people were encouraged to settle there.' Vicarage Field and the triangular field south of the road from Stanton Harcourt to Beard Mill enclose a large group of sites of different periods. The latter field was destroyed in 1944-45, after Mr. D. N. Riley had examined the larger ring-ditch in it and Mr. R. J. C. Atkinson the smaller.' Gravel-working also began in Vicarage Field in 1944, at which time Mrs. A. Williams was able to examine part of the area that was threatened. During September, 1951,' it became necessary to restart excavations in Vicarage Field when the gravel-pit of Messrs. Ivor Partridge & Sons (Beg broke) Ltd. was suddenly extended westward, involving a further two acres of ground. -

'Common Rights' - What Are They?

'Common Rights' - What are they? An investigation into rights of passage and rights of land use (or rights of common) Alan Shelley PG Dissertation in Landscape Architecture Cheltenham & Gloucester College of Higher Education April2000 Abstract There is a level of confusion relating to the expression 'common' when describing 'common rights'. What is 'common'? Common is a word which describes sharing or 'that affecting all alike'. Our 'common humanity' may be a term used to describe people in general. When we refer to something 'common' we are often saying, or implying, it is 'ordinary' or as normal. Mankind, in its earliest civilisation formed societies, usually of a family tribe, that expanded. Society is principled on community. What are 'rights'? Rights are generally agreed practices. Most often they are considered ethically, to be moral, just, correct and true. They may even be perceived, in some cases, to include duty. The evolution of mankind and society has its origins in the land. Generally speaking common rights have come from land-lore (the use of land). Conflicts have evolved between customs and the statutory rights of common people (the people of the commons). This has been influenced by Church (Canonical) law, from Roman formation, statutory enclosures of land and the corporation of local government. Privilege, has allowed 'freemen', by various customs, certain advantages over the general populace, or 'common people'. Unfortunately, the term no longer describes a relationship of such people with the land, but to their nationhood. Contents Page Common Rights - What are they?................................................................................ 1 Rights of Common ...................................................................................................... 4 Woods and wood pasture ............................................................................................ -

As a Largely Rural District the Highway Network Plays a Key Role in West Oxfordshire

Highways 8.9 As a largely rural district the highway network plays a key role in West Oxfordshire. The main routes include the A40 Cheltenham to Oxford, the A44 through Woodstock and Chipping Norton, the A361 Swindon to Banbury and the A4260 from Banbury through the eastern part of the District. These are shown on the Key Diagram (Figure 4.1). The provision of a good, reliable and congestion free highway network has a number of benefits including the provision of convenient access to jobs, services and facilities and the potential to unlock and support economic growth. Under the draft Local Plan, the importance of the highway network will continue to be recognised with necessary improvements to be sought where appropriate. This will include the delivery of strategic highway improvements necessary to support growth. 8.10 The A40 is the main east-west transport route with congestion on the section between Witney and Oxford being amongst the most severe transport problems in Oxfordshire and acting as a potential constraint to economic growth. One cause of the congestion is insufficient capacity at the Wolvercote and Cutteslowe roundabouts (outside the District) with the traffic lights and junctions at Eynsham and Cassington (inside the District) adding to the problem. Severe congestion is also experienced on the A44 at the Bladon roundabout, particularly during the morning peak. Further development in the District will put additional pressure on these highly trafficked routes. 8.11 In light of these problems, Oxfordshire County Council developed its ‘Access to Oxford’ project and although Government funding has been withdrawn, the County Council is continuing to seek alternative funding for schemes to improve the northern approaches to Oxford, including where appropriate from new development. -

Wall-Painting at South Leigh

A 'Fifteenth-Century' Wall-Painting at South Leigh By JOHN EDWARDS SUMMARY This paper is confined 10 one of Ihe several wall-painlings al Soulh Leigh church which Wert reslored in 1872, namely, Ihe Soul- Weighing on Ihe soulh wall of Ihe nave. In il,Jrom evidence based nol merely on Ihe records, but also on several points arising from a detailed examination of the wall-painting itself, it is hoped to demonstralt that the Soul- Weighing can no longer be accepted as even a htal!J-handtd repainting of a lale 151h cenlury original, bUI is now due for a re-appraisal in its own righl as an example of Victonan religious art. which took its subjectJrom the anginal medieval wall-painting but is about twiu as large. n the late 1860s the Bishop of Oxford, at the instigation of the lord of the manor, I Coningsby Sibthorp of Canwick Hall, Lincolnshire,' created the parish of South Leigh out of the existing parish of Stanton Harcourt, the first vicar of the new parish, the Rev. Gerard Moultrie, being appointed in 1869.' The church of South Leigh, SI. James the Great, has a rebuilt Norman chancel, but the rest is late 15th-century.] Considerable restoration of the church was necessary, and was already in progress by 27 th January, 1872/ in the course of which it was reported that 'on removing the whitewash from the walls remarkable wall-paintings have come to light'. ~ The restoration of the wall-paintings was carried out at a cost of £85 by Messrs. Burlison & Grylls; they had been appointed on Sibthorp's express nomination.' This was a somewhat curious choice, since they were not restorers of wall-paintings by profession, but after both had trained in the studios of Clayton & Bell, the celebrated makers of stained glass, they themselves had set up in the stained glass business only a few years before, in 1868.' No doubt (he pressure of work caused by the amount of Victorian church-restoration was such that those concerned had to turn their hands to whatever was required. -

St MICHAEL, Stanton Harcourt

OXFORD DIOCESE PILGRIM PROJECT OXFORD DIOCESE PILGRIM PROJECT You might also like to visit other nearby Oxford Diocese Pilgrim Project: churches in the Pilgrim Project: St Michael, Stanton Harcourt Dorchester Abbey OX29 5RJ Ancient Abbey Church Website: www.achurchnearyou.com/ St Peter Ad Vincula, South Newington stanton-harcourt-st-michael Exceptional medieval wall paintings St Margaret of Antioch, Binsey Alice in Wonderland’s treacle well PILGRIMAGE PRAYER Pilgrim God, You are our origin and our destination. Travel with us, we pray, in every pilgrimage of faith, and every journey of the heart. Give us the courage to set off, the nourishment we need to travel well, and the welcome we long for at our journey’s end. So may we grow in grace and love for you and in the service of others. through Jesus Christ our Lord, Amen John Pritchard, Bishop of Oxford ST MICHAEL, Illustrations by Brian Hall © Diocese of Oxford STANTON HARCOURT St Michael, Stanton Harcourt, mentioned in the Domesday Book, lies in a bend of the River Thames. St Michael’s church is thought to have been built in 1130 by Queen Adeliza, the second wife of Henry I, who owned the Manor. The church is famous for the shrine of the Anglo- Saxon female saint St Edburg, rescued in 1537 from Bicester Priory during the Dissolution of the Monasteries. In the late 12th century Queen Adeliza granted On the extreme right of the screen are two Alexander Pope who was sitting in the tower of the manor of Stantone to her kinswoman panels which escaped the attentions of the the Harcourt Manor Chapel and witnessed two Millicent, wife of Richard de Camville. -

Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxford Archdeacons’ Marriage Bond Extracts 1 1634 - 1849 Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1634 Allibone, John Overworton Wheeler, Sarah Overworton 1634 Allowaie,Thomas Mapledurham Holmes, Alice Mapledurham 1634 Barber, John Worcester Weston, Anne Cornwell 1634 Bates, Thomas Monken Hadley, Herts Marten, Anne Witney 1634 Bayleyes, William Kidlington Hutt, Grace Kidlington 1634 Bickerstaffe, Richard Little Rollright Rainbowe, Anne Little Rollright 1634 Bland, William Oxford Simpson, Bridget Oxford 1634 Broome, Thomas Bicester Hawkins, Phillis Bicester 1634 Carter, John Oxford Walter, Margaret Oxford 1634 Chettway, Richard Broughton Gibbons, Alice Broughton 1634 Colliar, John Wootton Benn, Elizabeth Woodstock 1634 Coxe, Luke Chalgrove Winchester, Katherine Stadley 1634 Cooper, William Witney Bayly, Anne Wilcote 1634 Cox, John Goring Gaunte, Anne Weston 1634 Cunningham, William Abbingdon, Berks Blake, Joane Oxford 1634 Curtis, John Reading, Berks Bonner, Elizabeth Oxford 1634 Day, Edward Headington Pymm, Agnes Heddington 1634 Dennatt, Thomas Middleton Stoney Holloway, Susan Eynsham 1634 Dudley, Vincent Whately Ward, Anne Forest Hill 1634 Eaton, William Heythrop Rymmel, Mary Heythrop 1634 Eynde, Richard Headington French, Joane Cowley 1634 Farmer, John Coggs Townsend, Joane Coggs 1634 Fox, Henry Westcot Barton Townsend, Ursula Upper Tise, Warc 1634 Freeman, Wm Spellsbury Harris, Mary Long Hanburowe 1634 Goldsmith, John Middle Barton Izzley, Anne Westcot Barton 1634 Goodall, Richard Kencott Taylor, Alice Kencott 1634 Greenville, Francis Inner