Wall-Painting at South Leigh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Postal Sector Council Alternative Sector Name Month (Dates)

POSTAL COUNCIL ALTERNATIVE SECTOR NAME MONTH (DATES) SECTOR BN15 0 Adur District Council Sompting, Coombes 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN15 8 Adur District Council Lancing (Incl Sompting (South)) 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN15 9 Adur District Council Lancing (Incl Sompting (North)) 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN42 4 Adur District Council Southwick 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN43 5 Adur District Council Old Shoreham, Shoreham 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN43 6 Adur District Council Kingston By Sea, Shoreham-by-sea 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN12 5 Arun District Council Ferring, Goring-by-sea 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN16 1 Arun District Council East Preston 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN16 2 Arun District Council Rustington (South), Brighton 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN16 3 Arun District Council Rustington, Brighton 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN16 4 Arun District Council Angmering 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN17 5 Arun District Council Littlehampton (Incl Climping) 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN17 6 Arun District Council Littlehampton (Incl Wick) 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN17 7 Arun District Council Wick, Lyminster 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN18 0 Arun District Council Yapton, Walberton, Ford, Fontwell 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN18 9 Arun District Council Arundel (Incl Amberley, Poling, Warningcamp) -

Discussion Papers in Economic and Social History

U N I V E R S I T Y O F O X F O R D Discussion Papers in Economic and Social History Number 26, Nov. 1998 AN ARDUOUS AND UNPROFITABLE UNDERTAKING: THE ENCLOSURE OF STANTON HARCOURT, OXFORDSHIRE1 DAVID STEAD Nuffield College, University of Oxford 1 I owe much to criticism and suggestion from Simon Board, Tracy Dennison, Charles Feinstein, Michael Havinden, Avner Offer, and Leigh Shaw-Taylor. The paper also benefited from comments at the Economic and Social History Graduate Workshop, Oxford University, and my thanks to the participants. None of these good people are implicated in the views expressed here. For efficient assistance with archival enquiries, I am grateful to the staff at the Bodleian Library, Oxford University (hereafter Bodl.), Oxfordshire Archives (OA), the House of Lords Record Office (HLRO), West Sussex Record Office (WSRO), and the Department of Archives and Manuscripts, Reading University. I thank Michael Havinden, John Walton, and the Warden and Fellows of All Souls College for permitting citation of material. Financial assistance from the Economic and Social Research Council is gratefully acknowledged. Discussion Papers in Economic and Social History are edited by: James Foreman-Peck St. Antony’s College, Oxford, OX2 6JF Jane Humphries All Souls College, Oxford OX1 4AL Susannah Morris Nuffield College, Oxford OX1 1NF Avner Offer Nuffield College, Oxford, OX1 1NF David Stead Nuffield College, Oxford, OX1 1NF papers may be obtained by writing to Avner Offer, Nuffield College, Oxford, OX1 1NF email:[email protected] 2 Abstract This paper provides a case study of the parliamentary enclosure of Stanton Harcourt, Oxfordshire. -

As a Largely Rural District the Highway Network Plays a Key Role in West Oxfordshire

Highways 8.9 As a largely rural district the highway network plays a key role in West Oxfordshire. The main routes include the A40 Cheltenham to Oxford, the A44 through Woodstock and Chipping Norton, the A361 Swindon to Banbury and the A4260 from Banbury through the eastern part of the District. These are shown on the Key Diagram (Figure 4.1). The provision of a good, reliable and congestion free highway network has a number of benefits including the provision of convenient access to jobs, services and facilities and the potential to unlock and support economic growth. Under the draft Local Plan, the importance of the highway network will continue to be recognised with necessary improvements to be sought where appropriate. This will include the delivery of strategic highway improvements necessary to support growth. 8.10 The A40 is the main east-west transport route with congestion on the section between Witney and Oxford being amongst the most severe transport problems in Oxfordshire and acting as a potential constraint to economic growth. One cause of the congestion is insufficient capacity at the Wolvercote and Cutteslowe roundabouts (outside the District) with the traffic lights and junctions at Eynsham and Cassington (inside the District) adding to the problem. Severe congestion is also experienced on the A44 at the Bladon roundabout, particularly during the morning peak. Further development in the District will put additional pressure on these highly trafficked routes. 8.11 In light of these problems, Oxfordshire County Council developed its ‘Access to Oxford’ project and although Government funding has been withdrawn, the County Council is continuing to seek alternative funding for schemes to improve the northern approaches to Oxford, including where appropriate from new development. -

Oxfordshire. Far 365

TRADES DIRECTORY.] OXFORDSHIRE. FAR 365 Chesterman Richard Austin, Cropredy Cottrell Richard, Shilton, Faringdon Edden Charles, Thame lawn, Cropredy, Leamington Cox: Amos,East end,North Leigb,Witney Edden William, 54 High street, Thame ChichesterW.Lwr.Riding,N.Leigh,lHny Cox: Charles, Dnnsden, Reading Eden James, Charlbury S.O Child R. Astley bridge, Merton, Bicester Cox: Charles, Kidmore, Reading Edginton Charles, Kirtlington, Oxford Chi!lingworth Jn. Chippinghurst,Oxford Cox: Mrs. Eliza, Priest end, Thame Edginton Henry Bryan, Upper court, Chillingworth John, Cuddesdon, Oxford Cox: Isaac, Standhill,Henley-on-Thames Chadlington, Charlbury S.O Chillingworth J. Little Milton, Tetswrth Cox: :!\Irs. Mary, Yarnton, Oxford Edginton William, Merris court, Lyne- ChiltonChs.P.Nethercote,Tackley,Oxfrd Cox Thomas, Horton, Oxford ham, Chipping Norton Chown Brothers, Lobb, Tetsworth Cox Thos. The Grange,Oddington,Oxfrd Edmans Thos. Edwd. Kingsey, Thame Chown Mrs. M. Mapledurham, Reading Cox William, Horton, Oxford Edmonds Thomas Henry, Alvescott S. 0 Cho wn W. Tokers grn. Kid more, Reading Craddock F. Lyneham, Chipping "N orton Ed wards E. Churchill, Chipping N orton Churchill John, Hempton, Oxford CraddockFrank,Pudlicot,Shortbampton, Edwards William, Ramsden, Oxford Churchill William, Cassington, Oxford Charlbury S.O Eeley James, Horsepath, Oxford Clack Charles, Ducklington, Witney Craddock John W. Kencott, Swindon Eggleton Hy. David, Cbinnor, Tetswrth Clack William, Minster Lovell, Witney Craddock R. OverKiddington,Woodstck Eggleton John, Stod:.enchurch, Tetswrth Clapham C.Kencott hill,Kencott,Swindn Craddock William, Brad well manor, Eldridge John, Wardington, Banbury Clapton G. Osney hl.N orthLeigh, Witney Brad well, Lechlade S. 0 (Gloucs) Elkingto::1 Thos. & Jn. Claydon, Banbry Clapton James, Alvescott S.O Crawford Joseph, Bletchington, Oxford Elliott E. -

Cassington &Worton News

CASSINGTON & WORTON NEWS News and views from the parish of Cassington and Worton December 2011 – Issue 414 . visit our village website . www.cassington.info . BELL FAIR SUCCESS The Friends of St Peter's would like to thank all of those who came to support the Bell Fair on October 29th, and we are extremely grateful to the Hatwell family who offered to stage the fair specifically to raise money for the bells. The day was a great success, raising over £1500 towards the restoration of the church bells, which is planned for 2012. The fairground rides were very popular with even some of the village's more mature residents enjoying themselves on the biggest ride (in spite of the screaming!). Thanks too for all of those who helped at the barbeque, the skittles, the afternoon teas, the quiz and the supper. It was also good to have some live music from talented local youngsters Catch 23 in the afternoon, and from the Cassington Singers and C Factor winner Kevin Perisi in the evening. Advertising rates (increasing from Jan ‘12) Local ‘what’s on’ and fund-raising stuff is free. We hope that you enjoyed seeing the plans for the proposed works and the Simple local services, ‘for sales’ etc, are also free slide show of the tour of the tower which were displayed in the Village Hall. on noticeboard. Suitable commercial business are invited to Many thanks to The Red Lion for putting on a splendid firework display on support our community by buying advertising space ... 5th November and for allowing us to shake buckets at those coming to watch 1/8 page, £5 (£50 per year) – this contributed over £80 to the Bell Fund. -

Rushy Common Walk

Artist Residence OXFORDSHIRE SOUTH LEIGH & RUSHY COMMON Distance: 3.5 miles Time: allow 2 hours A local adventure - it can get very muddy so make use of our Hunter wellies and get stuck into countryside living! 1. Leaving the village on the Stanton Harcourt road, take the footpath on the right just beyond the South Leigh sign past the front of Tar Wood Lodge and through the gate with the yellow arrow. Continue ahead keeping Tar Wood on your right. As you pass under the pylons you will see Wytham Hill and Great Wood, then Boars Hill to your left. Follow the hedge and look back to see Eynsham Hall Park beyond College Farm. 2. Continue straight ahead when joining the track with a gate in the hedge on your right. The track to the left leads to Stanton Harcourt. After passing beneath a large oak tree look through the gap on your right where you may see many peewits, which nest on the ground. There are various birds here including long tailed tits, blue tits, chaffinches, and larks overhead. 3. Turn right when you reach the Stanton Harcourt to Cogges road for about 200 yards then take the footpath on the right just before The Firs. This track climbs gently between mixed hedges including dog roses, with rosebay willow herb and cow parsley. Rabbits and hares can also be seen along here. When reaching the opening bear left keeping the hedge on your left then continue straight on passing the gap on your left, heading for the pylons. Look out for buzzards overhead and deer prints on the ground. -

'Income Tax Parish'. Below Is a List of Oxfordshire Income Tax Parishes and the Civil Parishes Or Places They Covered

The basic unit of administration for the DV survey was the 'Income tax parish'. Below is a list of Oxfordshire income tax parishes and the civil parishes or places they covered. ITP name used by The National Archives Income Tax Parish Civil parishes and places (where different) Adderbury Adderbury, Milton Adwell Adwell, Lewknor [including South Weston], Stoke Talmage, Wheatfield Adwell and Lewknor Albury Albury, Attington, Tetsworth, Thame, Tiddington Albury (Thame) Alkerton Alkerton, Shenington Alvescot Alvescot, Broadwell, Broughton Poggs, Filkins, Kencot Ambrosden Ambrosden, Blackthorn Ambrosden and Blackthorn Ardley Ardley, Bucknell, Caversfield, Fritwell, Stoke Lyne, Souldern Arncott Arncott, Piddington Ascott Ascott, Stadhampton Ascott-under-Wychwood Ascott-under-Wychwood Ascot-under-Wychwood Asthall Asthall, Asthall Leigh, Burford, Upton, Signett Aston and Cote Aston and Cote, Bampton, Brize Norton, Chimney, Lew, Shifford, Yelford Aston Rowant Aston Rowant Banbury Banbury Borough Barford St John Barford St John, Bloxham, Milcombe, Wiggington Beckley Beckley, Horton-cum-Studley Begbroke Begbroke, Cutteslowe, Wolvercote, Yarnton Benson Benson Berrick Salome Berrick Salome Bicester Bicester, Goddington, Stratton Audley Ricester Binsey Oxford Binsey, Oxford St Thomas Bix Bix Black Bourton Black Bourton, Clanfield, Grafton, Kelmscott, Radcot Bladon Bladon, Hensington Blenheim Blenheim, Woodstock Bletchingdon Bletchingdon, Kirtlington Bletchington The basic unit of administration for the DV survey was the 'Income tax parish'. Below is -

Thames Valley Environmental Records Centre

Thames Valley Environmental Records Centre Sharing environmental information in Berkshire and Oxfordshire Local Wildlife Sites in West Oxfordshire, Oxfordshire - 2018 This list includes Local Wildlife Sites. Please contact TVERC for information on: site location and boundary area (ha) designation date last survey date site description notable and protected habitats and species recorded on site Site Site Name District Parish Code 20A01 Old Gravel Pit near Little West Oxfordshire Little Faringdon Faringdon 20H01 The Bog West Oxfordshire Filkins and Broughton Poggs 20N01 Shilton Bradwell Grove Airfield West Oxfordshire Kencot 20S02 Manor Farm Meadow West Oxfordshire Crawley 20S09 Willow Meadows West Oxfordshire Alvescot 20T02 Carterton Grassland West Oxfordshire Carterton 21I01 Taynton Bushes West Oxfordshire Bruern 21I02 Tangley Woods West Oxfordshire Bruern 21L02 Burford Wet Grassland West Oxfordshire Fulbrook 21M01 Taynton Down Quarry West Oxfordshire Taynton 21M02/1 Dean Bottom West Oxfordshire Fulbrook 21S01 Widley Copse West Oxfordshire Swinbrook and Widford 21U01 Bruern Woods West Oxfordshire Bruern 21W01 Swinbrook Watercress Beds West Oxfordshire Swinbrook and Widford Valley 22X03 Meadow at Besbury Lane West Oxfordshire Churchill 23V01 Oakham Quarry West Oxfordshire Rollright 30D08 Huck's Copse West Oxfordshire Brize Norton 30K01/3 Shifford Chimney Meadows West Oxfordshire Aston Bampton and Shifford 30N01 Mouldens Wood and Davis West Oxfordshire Ducklington Copse 30N02 Barleypark Wood West Oxfordshire Ducklington 30S02 Home -

The Methodist Legend of South Leigh an Article in Celebration of the 250Th Anniversary of the Ordination of John Wesley

The Methodist Legend of South Leigh An Article in Celebration of the 250th Anniversary of the Ordination of John Wesley. Sunday. September 19. 1725 by E. Ralph Bates Guide books specially written for the benefit of Methodist pilgrims in England point to the parish church of the small village of Soutll Leigh (sometimes written and more usually pronounced Lye), some two miles to the southeast of Witney and nine miles to the west of Oxford, as the scene of J ohn Wesley's first preach ing. l A brass plate affixed to the pulpit supports them. They follow a long line of Wesley historians. Over a century ago Tyerman wrote, "Wesley's first sermon was preached at South Leigh." 2 In fixing tile date as September 26, 1725, which was the Sunday im mediately following his ordination, it is clear that Tyerman intended his sentence to mean, "At South Leigh Wesley conducted his first preaching service." Curnock followed Tyerman and added that _ the text was Matthew 6: 33, "Seek ye first the kingdom of God, and His righteousness." 3 Telford accepted Tyerman's word as to place, but was content to give the date as "soon after his ordination." 4 Doughty accepted both place and date.5 More recently, Dr. Green of Oxford has accepted Tyerman's word.6 Baker wrote more cau tiously, "Wesley's first sermon was apparently preached on Sunday, 26th September 1725, exactly a week after his ordination." 7 While not discarding Tyerman's conjecture-for conjecture it was-the problem of accepting it was hinted at. -

Members of West Oxfordshire District Council 1997/98

LOWLANDS Councillor Name Address Ward and Parishes BARRETT, M A Wychwoods, Church View, Bampton, Bampton and Clanfield Oxon, OX18 2NE (Parishes: Bampton; Clanfield; Black Bourton) Tel: 01993 202561 [email protected] BOOTY, M R Calais Oak Farm, Bampton, Oxon, Bampton and Clanfield OX18 2BW (Parishes: Bampton; Clanfield; Black Bourton) Tel: 01993 851003 [email protected] CROSSLAND, 111 Burford Road, Carterton North West MRS M J Carterton, Oxon, OX18 1AJ (Parishes: Carterton Rock Farm; Carterton (Vice Chairman) Shillbrook) Tel: 01993 212654 [email protected] ENRIGHT, D S T 85 Newland, Witney, Witney East Oxon, OX28 3JW (Parish: Witney East) Tel: 01993 200012 [email protected] FENTON, Westfield House, Standlake, Aston and Stanton MRS E H N Bampton Road, Aston, Harcourt Oxon, OX18 2BU (Parishes: Aston, Cote, Shifford & Chimney; Tel: 01993 852082 Standlake; Northmoor; Stanton Harcourt; Mob: 07736 769629 Hardwick with Yelford) [email protected] GOOD, S J 3 Steadys Lane Standlake, Aston and Stanton Stanton Harcourt Harcourt Oxon, OX29 5RL (Parishes: Aston, Cote, Shifford & Chimney; Tel: 01865 882668 Standlake; Northmoor; Stanton Harcourt; [email protected] Hardwick with Yelford) HAINE, J 13 Poplar Farm Close, Milton under Milton under Wychwood Wychwood, Oxon, OX7 6LX (Parishes: Milton under Wychwood; Bruern; Tel: 01993 830078 Fifield; Idbury) [email protected] HANDLEY, P J Westbourne, Pie Corner, Shilton, Carterton North West Oxon, OX18 4AW Tel: 01993 842147 (Parishes: -

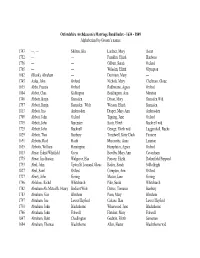

Alphabetized by Groom's Names

Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Alphabetized by Groom’s names 1743 ---, --- Shilton, Bks Lardner, Mary Ascot 1752 --- --- Franklin, Elizth Hanboro 1756 --- --- Gilbert, Sarah Oxford 1765 --- --- Wilsden, Elizth Glympton 1682 (Blank), Abraham --- Devinton, Mary --- 1745 Aales, John Oxford Nichols, Mary Cheltnam, Glouc 1635 Abba, Francis Oxford Radbourne, Agnes Oxford 1804 Abbot, Chas Kidlington Boddington, Ann Marston 1746 Abbott, Benjn Ramsden Dixon, Mary Ramsden Wid 1757 Abbott, Benjn Ramsden Widr Weston, Elizth Ramsden 1813 Abbott, Jno Ambrosden Draper, Mary Ann Ambrosden 1709 Abbott, John Oxford Tipping, Jane Oxford 1719 Abbott, John Burcester Scott, Elizth Bucknell wid 1725 Abbott, John Bucknell George, Elizth wid Luggershall, Bucks 1829 Abbott, Thos Banbury Treadwell, Kitty Clark Finmere 1691 Abbotts, Ricd Heath Marcombe, Anne Launton 1635 Abbotts, William Hensington Humphries, Agnes Oxford 1813 Abear, Edmd Whitfield Greys Bowlby, Mary Ann Caversham 1775 Abear, Jno Burton Walgrove, Bks Piercey, Elizth Rotherfield Peppard 1793 Abel, John Upton St Leonard, Glouc Bailey, Sarah St Rollright 1827 Abel, Saml Oxford Compton, Ann Oxford 1727 Abery, John Goring Mason, Jane Goring 1796 Ablolom, Richd Whitchurch Pike, Sarah Whitchurch 1742 Abraham Als Metcalfe, Henry Bodicot Widr Dawes, Tomasin Banbury 1783 Abraham, Geo Bloxham Penn, Mary Bloxham 1797 Abraham, Jno Lower Heyford Calcote, Han Lower Heyford 1730 Abraham, John Blackthorne Whorwood, Jane Blackthorne 1766 Abraham, John Fritwell Fletcher, Mary Fritwell 1847 -

The Medieval Rural Landscape, C AD 1000–1500 by James Bond

THE THAMES THROUGH TIME The Archaeology of the Gravel Terraces of the Upper and Middle Thames: The Thames Valley in the Medieval and Post-Medieval Periods AD 1000–2000 The Medieval Rural Landscape AD 1000–1500 THE THAMES THROUGH TIME The Archaeology of the Gravel Terraces of the Upper and Middle Thames: The Thames Valley in the Medieval and Post-Medieval Periods AD 1000-2000 The medieval rural landscape, c AD 1000–1500 by James Bond INTRODUCTION The study of the medieval rural landscape entails a long history of research. The late 19th and early 20th century saw several pioneering works by historians who aimed to shift the spotlight from matters of political and religious history towards a better understanding of the countryside (eg Seebohm 1883; Vinogradoff 1892; Maitland 1897). The work of Gray (1915) built on these early studies by emphasising the considerable evidence of regional variation in landscape character. By the 1950s, interest in the medieval rural landscape, and particularly of the medieval village, was accelerating, with research by Beresford (1954) and W G Hoskins (1955) amongst the most prominent. The emerging knowledge base was now becoming founded on archaeological research and this was increasingly complemented by architectural (eg Long 1938–1941; Faulkner 1958; Currie 1992) and place/field-name studies (Gelling 1954; 1976; Bond 1982; Faith 1998) which added further detail and context to understanding of medieval settlements. Broader appreciation of the wider landscape, in terms of how it was used, organised and perceived by its medieval inhabitants have also been examined from the perspective of the elite (eg Creighton 2009; Langton 2010) and increasingly from the point of view of the peasant (eg Faith 1997; Dyer 2014).