The Medieval Rural Landscape, C AD 1000–1500 by James Bond

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oxfordshire. Chipping Nor Ton

DIRI::CTOR Y. J OXFORDSHIRE. CHIPPING NOR TON. 79 w the memory of Col. Henry Dawkins M.P. (d. r864), Wall Letter Box cleared at 11.25 a.m. & 7.40 p.m. and Emma, his wife, by their four children. The rents , week days only of the poor's allotment of so acres, awarded in 1770, are devoted to the purchase of clothes, linen, bedding, Elementary School (mixed), erected & opened 9 Sept. fuel, tools, medical or other aid in sickness, food or 1901 a.t a. cost of £ r,ooo, for 6o children ; average other articles in kind, and other charitable purposes; attendance, so; Mrs. Jackson, mistress; Miss Edith Wright's charity of £3 I2S. is for bread, and Miss Daw- Insall, assistant mistress kins' charity is given in money; both being disbursed by the vicar and churchwardens of Chipping Norton. .A.t Cold Norron was once an Augustinian priory, founded Over Norton House, the property of William G. Dawkina by William Fitzalan in the reign of Henry II. and esq. and now the residence of Capt. Denis St. George dedicated to 1818. Mary the Virgin, John the Daly, is a mansion in the Tudor style, rebuilt in I879, Evangelist and S. Giles. In the reign of Henry VII. and st'anding in a well-wooded park of about go acres. it was escheated to the Crown, and subsequently pur William G. Dawkins esq. is lord of the manor. The chased by William Sirlith, bishop of Lincoln (I496- area is 2,344 acres; rateable value, £2,oo6; the popula 1514), by-whom it was given to Brasenose College, Ox tion in 1901 was 3so. -

Appleton with Eaton Community Plan

Appleton with Eaton Community Plan Final Report & Action Plan July 2010 APPLETON WITH EATON COMMUNITY PLAN PART 1: The Context Section A: The parish of Appleton with Eaton is situated five miles south west of Oxford. It Appleton with Eaton consists of the village of Appleton and the hamlet of Eaton, together totalling some 900 inhabitants. It is surrounded by farmland and woods, and bordered by the Thames to the north-west. Part of the parish is in the Oxford Green Belt, and the centre of Appleton is a conservation area. It is administered by Oxfordshire County Council, The Vale of the White Horse District Council and Appleton with Eaton Parish Council. Appleton and Eaton have long histories. Appleton is known to have been occupied by the Danes in 871 AD, and both settlements are mentioned in the Doomsday Book. Eaton celebrated its millennium in 1968. The parish’s buildings bear witness to its long history, with the Manor House and St Laurence Church dating back to the twelfth century, and many houses which are centuries old. Appleton’s facilities include a community shop and part-time post office, a church, a chapel, a village hall, a primary school, a pre-school, a pub, a sportsfield and a tennis club. Eaton has a pub. There is a limited bus service linking the parish with Oxford, Swindon, Southmoor and Abingdon. There are some twenty-five clubs and societies in Appleton, and a strong sense of community. Businesses in the parish include three large farms, a long-established bell-hanging firm, a saddlery, an electrical systems firm and an increasing number of small businesses run from home. -

11 Witney - Hanborough - Oxford

11 Witney - Hanborough - Oxford Mondays to Saturdays notes M-F M-F S M-F M-F Witney Market Square stop C 06.14 06.45 07.45 - 09.10 10.10 11.15 12.15 13.15 14.15 15.15 16.20 - Madley Park Co-op 06.21 06.52 07.52 - - North Leigh Masons Arms 06.27 06.58 07.58 - 09.18 10.18 11.23 12.23 13.23 14.23 15.23 16.28 17.30 Freeland Broadmarsh Lane 06.35 07.06 08.07 07.52 09.27 10.27 11.32 12.32 13.32 14.32 15.32 16.37 17.40 Long Hanborough New Road 06.40 07.11 08.11 07.57 09.31 10.31 11.36 12.36 13.36 14.36 15.36 16.41 Eynsham Spareacre Lane 06.49 07.21 08.20 09.40 10.40 11.45 12.45 13.45 14.45 15.45 16.50 Eynsham Church 06.53 07.26 08.24 08.11 09.44 10.44 11.49 12.49 13.49 14.49 15.49 16.54 17.49 Botley Elms Parade 07.06 07.42 08.33 08.27 09.53 10.53 11.58 12.58 13.58 14.58 15.58 17.03 18.00 Oxford Castle Street 07.21 08.05 08.47 08.55 10.07 11.07 12.12 13.12 13.12 15.12 16.12 17.17 18.13 notes M-F M-F S M-F M-F S Oxford Castle Street E2 07.25 08.10 09.10 10.15 11.15 12.15 13.15 14.15 15.15 16.35 16.35 17.35 17.50 Botley Elms Parade 07.34 08.20 09.20 10.25 11.25 12.25 13.25 14.25 15.25 16.45 16.50 17.50 18.00 Eynsham Church 07.43 08.30 09.30 10.35 11.35 12.35 13.35 14.35 15.35 16.55 17.00 18.02 18.10 Eynsham Spareacre Lane 09.34 10.39 11.39 12.39 13.39 14.39 15.39 16.59 17.04 18.06 18.14 Long Hanborough New Road 09.42 10.47 11.47 12.47 13.47 14.47 15.47 17.07 17.12 18.14 18.22 Freeland Broadmarsh Lane 07.51 08.38 09.46 10.51 11.51 12.51 13.51 14.51 15.51 17.11 17.16 18.18 18.26 North Leigh Masons Arms - 08.45 09.55 11.00 12.00 13.00 -

February 2020

The Sprout into Act ap ion Le ! Better Botley, better planet! The Botley and North Hinksey ‘Big Green Day’ Fighting ClimateSaturday Feb.Change 29th 10.30am in Botley – 4pm on 29th February Activities will include Children’s play activities and face painting ‘Dr. Bike’ cycle maintenance Seed planting and plant swap Entertainment, Photobooth, food and drink ‘Give and take’ - bring your unwanted books, Short talks on what we can do in our homes music and clothing and our community More information at: https://leap-into-action.eventbrite.co.uk The newsletter for North HinkseyABC & Botley Association for Botley Communities Issue 144 February 2020 1 The Sprout Issue 144, February 2020 Contents 3 Letters to the Editor Brownies Christmas Treats 5 Leap into Action 25 Botley Babies and Toddlers 9 Taekwondo for everyone 27 Our New Community Hall 13 the First Cumnor Hill 31 Recycling Properly 17 Dance-outs and Saturdads 35 Friendly Running Group 19 Planning Applications 37 Scouts festive fun 21 Eating to Save the Planet 41 Randoms 43 Local organizations From the Editor Welcome to the first Sprout of 2020! As befits a decade in which there is everything to play for on the climate front, this month’s offering has several articles designed to help us get into gear. Recycling properly (p 31) shows how to make your recycling effective. Eating to Save the Planet (p21) is an account of the third talk in Low Carbon West Oxford’s series Act Now. (The fourth will be on Avoiding Waste on 8th February.) LCWO is a priceless local resource, as is the waste-busting Oxford Foodbank. -

Settlement Type

Design Guide 5 Settlement Type www.westoxon.gov.uk Design Guide 5: Settlement Type 2 www.westoxon.gov.uk Design Guide 5: Settlement Type 5.1 SETTLEMENT TYPE Others have an enclosed character with only limited views. Open spaces within settlements, The settlements in the District are covered greens, squares, gardens – even wide streets – by Local Plan policies which describe the contribute significantly to the unique form and circumstances in which any development will be character of that settlement. permitted. Most new development will occur in sustainable locations within the towns and Where development is permitted, the character larger villages where a wide range of facilities and and context of the site must be carefully services is already available. considered before design proposals are developed. Fundamental to successfully incorporating change, Settlement character is determined by a complex or integrating new development into an existing series of interactions between it and the landscape settlement, is a comprehensive understanding of in which it is set – including processes of growth the qualities that make each settlement distinctive. or decline through history, patterns of change in the local economy and design or development The following pages represent an analysis of decisions by landowners and residents. existing settlements in the District, looking at the pattern and topographic location of settlements; As a result, the settlements of West Oxfordshire as well as outlining the chief characteristics of all vary greatly in terms of settlement pattern, scale, of the settlements in the District (NB see 5.4 for spaces and building types. Some villages have a guidance on the application of this analysis). -

South Oxfordshire Zone Botley 5 ©P1ndar 4 Centre©P1ndart1 ©P1ndar

South_Oxon_Network_Map_South_Oxon_Network_Map 08/10/2014 10:08 Page 1 A 3 4 B4 0 20 A40 44 Oxford A4 B B 4 Botley Rd 4 4017 City 9 South Oxfordshire Zone Botley 5 ©P1ndar 4 Centre©P1ndarT1 ©P1ndar 2 C 4 o T2 w 1 le 4 y T3 A R A o 3 a 4 d Cowley Boundary Points Cumnor Unipart House Templars Ox for Travel beyond these points requires a cityzone or Square d Kenilworth Road Wa Rd tl SmartZone product. Dual zone products are available. ington Village Hall Henwood T3 R Garsington A420 Oxford d A34 Science Park Wootton Sandford-on-Thames C h 4 i 3 s A e Sugworth l h X13 Crescent H a il m d l p A40 X3 to oa R n 4 Radley T2 7 Stadhampton d X2 4 or B xf 35 X39 480 A409 O X1 X40 Berinsfield B 5 A 415 48 0 0 42 Marcham H A Abingdon ig Chalgrove A41 X34 h S 7 Burcot 97 114 T2 t Faringdon 9 X32 d Pyrton 00 7 oa 1 Abingd n R O 67 67A o x 480 B4 8 fo B 0 4 40 Clifton r P 67B 3 d a 45 B rk B A Culham R Sta Hampden o R n 114 T2 a T1 d ford R Rd d w D Dorchester d A4 rayton Rd Berwick Watlington 17 o Warborough 09 Shellingford B Sutton Long Salome 40 Drayton B B Courtenay Wittenham 4 20 67 d 67 Stanford in X1 8 4 oa Little 0 A R 67A The Vale A m Milton Wittenham 40 67A Milton 74 nha F 114 CERTAIN JOURNEYS er 67B a Park r Shillingford F i n 8 3 g Steventon ady 8 e d rove Ewelme 0 L n o A3 45 Fernham a G Benson B n X2 ing L R X2 ulk oa a 97 A RAF Baulking B d Grove Brightwell- 4 Benson ©P1ndar67 ©P1ndar 0 ©P1ndar MON-FRI PEAK 7 Milton Hill 4 67A 1 Didcot Cum-Sotwell Old AND SUNDAYS L Uffington o B 139 n Fa 67B North d 40 A Claypit Lane 4 eading Road d on w 1 -

Park and Formal Garden Walks Icon Key 2 Formal Gardens Exit 20 Bladon Bridge Information Formal Gardens Lake

23 No vehicle access Vehicle Exit To Churchill’s Burial Site, 20 A4095 St Martin’s Church, Bladon P 10 11 8 9 5 4 13 6 7 6 Due to the Cascades One Way having essential A4095 Traffic 12 restoration works South there is no access. Lawn Formal 3 7 Gardens No access is possible 9 to The Boathouse for 8 2 your safety. 21 Hensington P 4 5 Drive Vehicle access only 2 3 1 1 A44 P 19 Woodstock Entrance 14 22 Pedestrian access only Rowing Boats 2 1 15 Great Lake 17 Hi gh Street Queen Pool 3 18 The water levels are lower due to the Cascade essential works taking place. Levels Market Street will be returned by the end of August. The town of Woodstock Visit wakeuptowoodstock.com 16 Park Farm this way This is not a public area. Flagstaff Information Point and Facilities Formal Garden exit YOUR ON-SITE 2 3 3 GUIDE East NEW Courtyard PALACE ENTRANCE ENTRANCE FORMAL GARDENS AUDIO GUIDE Entrance 2 Ditchley A44 1 Gate & TREASURE HUNT WHERE YOU The Palace and grounds are a working Estate and there are vehicles using the CAN ENTER TO WIN PRIZES roads. Please follow guidance on any safety signage around the site during EXIT your visit. All children under 12 years old must be supervised at all times. blenheimpalace.com/app MAP KEY KEEPING The Palace and grounds are a working Estate and there are YOU vehicles using the roads. Please follow guidance on any SAFE safety signage around the site during your visit. -

Title Page Tag Line 1 Priory Manor 2 Ambrosden a Select Development of 2, 3, 4 & 5 Bedroom Homes in Ambrosden, Oxfordshire a Warm Welcome

TITLE PAGE TAG LINE 1 PRIORY MANOR 2 AMBROSDEN A SELECT DEVELOPMENT OF 2, 3, 4 & 5 BEDROOM HOMES IN AMBROSDEN, OXFORDSHIRE A WARM WELCOME We pride ourselves in providing you with the expert help and advice you may need at all stages of buying a new home, to enable you to bring that dream within your reach. We actively seek regular feedback from our customers once they have moved into a Croudace home and use this information, alongside our own research into lifestyle changes to constantly improve our designs. Environmental aspects are considered both during the construction process and when new homes are in use and are of ever increasing importance. Our homes are designed both to reduce energy demands and minimise their impact on their surroundings. Croudace recognises that the quality of the new homes we build is of vital importance to our customers. Our uncompromising commitment to quality extends to the first class service we offer customers when they have moved in and we have an experienced team dedicated to this task. We are proud of our excellent ratings in independent customer satisfaction surveys, which place us amongst the top echelon in the house building industry. Buying a new home is a big decision. I hope you decide to buy a Croudace home and that you have many happy years living in it. Russell Denness, Group Chief Executive PRIORY MANOR 2 AMBROSDEN A WARM WELCOME FROM CROUDACE HOMES 3 YOUR NEW COMMUNITY Located in the picturesque village of Ambrosden, Priory Manor is a select development of 2, 3, 4 & 5 bedroom homes bordering verdant open countryside with rolling hills leading to the River Cherwell. -

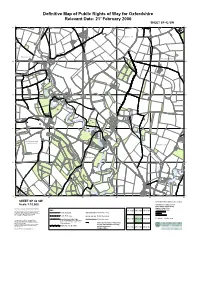

Definitive Map of Public Rights of Way for Oxfordshire Relevant Date: 21St February 2006 Colour SHEET SP 42 SW

Definitive Map of Public Rights of Way for Oxfordshire Relevant Date: 21st February 2006 Colour SHEET SP 42 SW 40 41 42 43 44 45 0004 8900 9600 4900 7100 0003 0006 2800 0003 2000 3700 5400 7100 8800 3500 5500 7000 8900 0004 0004 5100 8000 0006 25 365/1 Woodmans Cottage 25 Spring Close 9 202/31 365/3 202/36 1392 365/2 8891 365/17 202/2 400/2 8487 St Mary's Church 5/23 4584 36 0682 8381 Drain 202/30 CHURCH LANE 7876 2/56 20 8900 7574 365/2 2772 Westcot Barton CP 5568 2968 1468 1267 365/3 9966 4666 202/ 0064 8964 0064 5064 5064 202/29 Drain Spring 1162 0961 11 202/31 202/56 1359 0054 0052 365/1 0052 5751 0050 Oathill Farm Oathill Lodge 264/8 0050 264/7 6046 The Folly 0044 0044 6742 264/8 202/32 264/7 3241 7841 0940 7640 1839 2938 Drain 3637 7935 0033 0032 0032 0033 1028 4429 El Sub Sta 3729 7226 202/11 3124 6423 6023 Pond 0022 202/30 365/28 8918 0218 2618 7817 9217 4216 0015 0015 Spring 8214 2014 Willowbrook Cottage 9610 Radford House Enstone CP Radford 0001 House 202/32 Charlotte Cottage 224/1 Spring Steeple Barton CP Reservoir Nelson's Cottage 0077 6400 2000 3900 6200 2400 5000 7800 0005 3800 6400 0001 1300 3900 6100 0005 RADFORD Convent Cottage 8700 2600 6400 2000 3900 0002 1300 24 Convent Cottage 0002 5000 7800 0005 3800 4800 6400 365/4 0001 3900 6100 0005 24 Holly Tree House Brook Close 0005 Brook Close White House Farm Radford Lodge 365/3 365/5 365/4 8889 Radford Farm 0084 6583 8083 0084 202/33 4779 0077 0077 0077 8976 3175 202/45 9471 224/1 Barton Leys Farm Pond 2669 8967 Mill House Kennels 7665 Pond 202/44 2864 6561 6360 Glyme The -

Uffington and Baulking Neighbourhood Plan Website.10

Uffington and Baulking Neighbourhood Plan 2011-2031 Uffington Parish Council & Baulking Parish Meeting Made Version July 2019 Acknowledgements Uffington Parish Council and Baulking Parish Meeting would like to thank all those who contributed to the creation of this Plan, especially those residents whose bouquets and brickbats have helped the Steering Group formulate the Plan and its policies. In particular the following have made significant contributions: Gillian Butler, Wendy Davies, Hilary Deakin, Ali Haxworth, John-Paul Roche, Neil Wells Funding Groundwork Vale of the White Horse District Council White Horse Show Trust Consultancy Support Bluestone Planning (general SME, Characterisation Study and Health Check) Chameleon (HNA) Lepus (LCS) External Agencies Oxfordshire County Council Vale of the White Horse District Council Natural England Historic England Sport England Uffington Primary School - Chair of Governors P Butt Planning representing Developer - Redcliffe Homes Ltd (Fawler Rd development) P Butt Planning representing Uffington Trading Estate Grassroots Planning representing Developer (Fernham Rd development) R Stewart representing some Uffington land owners Steering Group Members Catherine Aldridge, Ray Avenell, Anna Bendall, Rob Hart (Chairman), Simon Jenkins (Chairman Uffington Parish Council), Fenella Oberman, Mike Oldnall, David Owen-Smith (Chairman Baulking Parish Meeting), Anthony Parsons, Maxine Parsons, Clare Roberts, Tori Russ, Mike Thomas Copyright © Text Uffington Parish Council. Photos © Various Parish residents and Tom Brown’s School Museum. Other images as shown on individual image. Executive Summary This Neighbourhood Plan (the ‘Plan’) was prepared jointly for the Uffington Parish Council and Baulking Parish Meeting. Its key purpose is to define land-use policies for use by the Planning Authority during determination of planning applications and appeals within the designated area. -

Town and Country Planning Acts Require the Following to Be Advertised 17/01394/FUL BRIZE NORTON DEP CONLB MAJ PROW

WEST OXFORDSHIRE DISTRICT COUNCIL Town and Country Planning Acts require the following to be advertised 17/01394/FUL BRIZE NORTON DEP CONLB MAJ PROW. Land South of Upper Haddon Farm Station Road Brize Norton. 17/01441/HHD SHIPTON UNDER WYCHWOOD CONLB PROW. The Old Beerhouse Simons Lane Shipton Under Wychwood. 17/01442/LBC SHIPTON UNDER WYCHWOOD LBC. The Old Beerhouse Simons Lane Shipton Under Wychwood. 17/01453/HHD WOODSTOCK CONLB. 126 Oxford Street Woodstock Oxfordshire. 17/01337/HHD LITTLE TEW CONLB. Manor House Chipping Norton Road Little Tew. 17/01338/LBC LITTLE TEW LBC. Manor House Chipping Norton Road Little Tew. 17/01392/LBC STANDLAKE LBC. Midway Lancott Lane Brighthampton. 17/01395/HHD DUCKLINGTON CONLB. 3 The Square Ducklington Witney. 17/01450/S73 GREAT TEW CONLB. Land at the Great Tew Estate Great Tew Oxfordshire. 17/01482/HHD FULBROOK PROW. Appledore Garnes Lane Fulbrook. 17/01627/HHD HAILEY CONLB PROW. 1 Middletown Cottages Middletown Hailey. 17/01332/HHD BAMPTON PROW. 5 Mercury Court Bampton Oxfordshire. 17/01255/FUL WITNEY CONLB. The Old Coach House Marlborough Lane Witney. 17/01397/FUL ALVESCOT CONLB. Rock Cottage Main Road Alvescot. 17/01406/HHD FILKINS AND BROUGHTON POGGS CONLB. Broctun House Broughton Poggs Lechlade. 17/01399/FUL CHASTLETON CONLB. School Kitebrook House Little Compton. 17/01409/HHD BRIZE NORTON CONLB. Yew Tree Cottage 60 Station Road Brize Norton. 17/01410/LBC BRIZE NORTON LBC. Yew Tree Cottage 60 Station Road Brize Norton. 17/01423/LBC ASCOTT UNDER WYCHWOOD LBC. The Old Farmhouse 15 High Street Ascott Under Wychwood. 17/01214/FUL WITNEY PROW. Cannon Pool Service Station 92 Hailey Road Witney. -

Oxfordshire Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by Bride’s Parish Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1635 Gerrard, Ralph --- Eustace, Bridget --- 1635 Saunders, William Caversham Payne, Judith --- 1635 Lydeat, Christopher Alkerton Micolls, Elizabeth --- 1636 Hilton, Robert Bloxham Cook, Mabell --- 1665 Styles, William Whatley Small, Simmelline --- 1674 Fletcher, Theodore Goddington Merry, Alice --- 1680 Jemmett, John Rotherfield Pepper Todmartin, Anne --- 1682 Foster, Daniel --- Anstey, Frances --- 1682 (Blank), Abraham --- Devinton, Mary --- 1683 Hatherill, Anthony --- Matthews, Jane --- 1684 Davis, Henry --- Gomme, Grace --- 1684 Turtle, John --- Gorroway, Joice --- 1688 Yates, Thos Stokenchurch White, Bridgett --- 1688 Tripp, Thos Chinnor Deane, Alice --- 1688 Putress, Ricd Stokenchurch Smith, Dennis --- 1692 Tanner, Wm Kettilton Hand, Alice --- 1692 Whadcocke, Deverey [?] Burrough, War Carter, Elizth --- 1692 Brotherton, Wm Oxford Hicks, Elizth --- 1694 Harwell, Isaac Islip Dagley, Mary --- 1694 Dutton, John Ibston, Bucks White, Elizth --- 1695 Wilkins, Wm Dadington Whetton, Ann --- 1695 Hanwell, Wm Clifton Hawten, Sarah --- 1696 Stilgoe, James Dadington Lane, Frances --- 1696 Crosse, Ralph Dadington Makepeace, Hannah --- 1696 Coleman, Thos Little Barford Clifford, Denis --- 1696 Colly, Robt Fritwell Kilby, Elizth --- 1696 Jordan, Thos Hayford Merry, Mary --- 1696 Barret, Chas Dadington Hestler, Cathe --- 1696 French, Nathl Dadington Byshop, Mary --- Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by