Article #7 Sidestroke

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Swim Strokes Pathways Swim Basics Swim Starters

Infant & Toddler Preschool School Age Teen & Adult 6 mos. –3 yrs. 3–5 yrs. 5–12 yrs. 12+ yrs. Program Overview Stages of Learning Stages A–B Stages 1–4 Stages 1–6 Stages 1–6 SWIM STARTERS SWIM BASICS SWIM STROKES PATHWAYS SWIM STARTERS SWIM BASICS (Safety Around Water) SWIM STROKES PATHWAYS Parent & child lessons Recommended skills for all to have around water Skills to support a healthy lifestyle Specialized tracks Parent* & child lessons Recommended skills for all to have around water Skills to support a healthy lifestyle Specialized tracks A B 1 2 3 4 5 6 Competition Water Water Water Water Water Stroke Stroke Stroke A B 1 2 3 4 5 6 Competition Discovery Exploration Acclimation Movement Stamina Introduction Development Mechanics Water Water Water Water Water Stroke Stroke Stroke Discovery Exploration Acclimation Movement Stamina Introduction Development Mechanics Blow bubbles Blow bubbles Submerge Submerge Submerge Endurance Endurance Endurance Leadership on surface, mouth & nose bob independently look at object on retrieve object in any stroke or any stroke or any stroke or Leadership assisted submerged, bottom chest-deep water combination of combination of combination of assisted Front glide strokes, 25 yd. strokes, 50 yd. strokes, 150 yd. Front tow assisted, to wall, Front glide Swim on front chin in water, Front tow 5 ft. 10 ft. (5 ft. 15 yd. (10 yd. Front crawl Front crawl Front crawl Recreation assisted blow bubbles, preschool) preschool) rotary breathing, bent-arm Introduces infants Focuses on Increases comfort Encourages Develops Introduces basic Introduces assisted Water exit 15 yd. recovery, 50 yd. and toddlers exploring body with underwater forward movement intermediate stroke technique breaststroke and technique on all Recreation Water exit independently Water exit Water exit 25 yd. -

La Sierra University Department of Health & Exercise Science

EXSC 115-1: Swim for Fitness Winter 2015 La Sierra University Department of Health & Exercise Science Instructor: Kimberly Feiler, MSHS, CHES Lifeguard Instructor & Water Safety Instructor Trainer (American Red Cross) [email protected] Office Hours: M/W/R 10:00 – 10:50 am, T/R 2:00 – 2:45 pm Class Dates: January 6 – March 12, 2015 (NO class meeting during Finals Week) Class Times: Tuesdays & Thursdays: 1:00 pm – 1:50 pm Location: LSU Pool *No class will be held if it is raining or if there is extreme wind. Make sure to check your email regularly for updates. Attire: Appropriate swimsuit; goggles; long hair needs to be tied back or in a swim cap; sunscreen. NO gym shorts, cut-offs, jewelry, gum, food, or cell phones. Integrity Statement: The student is expected to practice academic honesty in all activities related to this course. Original work is expected from the student. Refer to the Student Handbook for details. Course Objectives: Students will: 1. Participate to improve their cardiovascular and muscular fitness levels 2. Improve their swimming strokes Attendance: ALL classes are recommended for grading purposes. Workouts: Class activities will be explained by instructor and will include, but are not limited to: 1. Skills assessments (at beginning and end of quarter) 2. Kicks: flutter, frog, scissor, dolphin, egg-beater 3. Strokes: front crawl (free style); back crawl; breaststroke; elementary backstroke; sidestroke, over-arm sidestroke; butterfly; trudgen; inverted breaststroke 4. Floating; treading; diving (from surface of water, deck, diving blocks and board) 5. Water Safety: simple assists; reaching assists, with equipment; etc. -

Swim Level Descriptions

Swim Requirements Beginner I 1. Bobs – kids jump up and go under the water 10 times 2. Holding Breath Contest – goal: 10 seconds 3. Rhythmic Breathing – put face in the water and blow bubbles…when the child needs to breath, have them bring their face to the side 4. Prone Float – float on stomach, blowing bubbles with or without assistance…to pass they must be able to do it themselves 5. Prone Glide – arms above their head in streamline position, push off from ground with face in the water gliding on surface…goal: to glide a distance of 1 body length 6. Use of PFD (personal flotation devices) – use a kickboard independently Beginner II 1. Accomplish all the skills needed to pass Beginner I 2. Back Glide – arms above head in streamline position, push off from ground and glide across water without going under…goal: to glide a distance of 1 body length 3. Survival Float – arms out straight to the side, face in the water, bringing arms together in a clapping motion while lifting head up to take a breath then resuming prone float 4. Prone Glide with Kick – remain in streamline position with face in water 5. Back Guide with Kick – remain in streamline position on surface of water Beginner III 1. Accomplish all the skills needed to pass Beginner II 2. Crawl Stroke (15 Yards) – arms must come out of the water, face does not have to be in the water, kick continuously 3. Combined Stroke on Back (backstroke) – arms must come back straight touching ears, stomach up like a back float, kick continuously 4. -

Advanced Swimming, Phase II--Advanced Swimmer; Physical Education: 5551.48

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 093 879 SP 008 249 AUTHOR Gutting, Dick TITLE Advanced Swimming, Phase II--Advanced Swimmer; Physical Education: 5551.48. INSTITUTION Dade County Public Schools, Miami, Fla. PUB DATE 71 NOTE 16p.; An Authorized Course of Instruction for the Quinmester Program EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 BC -$1.50 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS Athletic Activities; Athletics; *Curriculum Guides; Intermediate Grades; *Physical Education; Secondary Grades; *Swimming IDENTIFIERS *Quinmester Program ABSTRACT GRADES OR AGES: Grades 7-12. SUBJECT MATTER: Advanced swimming. ORGANIZATION AND PHYSICAL APPEARANCE: The first two sections of the guides are devoted to course guidelines, description, and broad goal statement. The next two sections list behavioral and skill objectives and course content. The fifth section presents learning activities and teaching procedures. There is also a five-item bibliography. OBJECTIVES AND ACTIVITIES: The objective of the course is to provide the student with additional knowledge of swimming strokes and miscellaneous water skills which will make him an advanced swimmer. Basic skills, observed skills, and safety objectives are listed, as are learning activities. INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIALS: STUDENT ASSESSMENT: Evaluation checklists are included. (HMD) BEST COPYN\14',UZLE AUTHORIZED COURSE OF INSTRUCTION FOR THE DE PAP7MENT OF HEAL l- ", r A. 14E1, OWE NATIONAL INSTIT,!L OF UDT1(A,%C., . IDVANCFD SWIMMING !EASE TI - ADVANCED SWI711,R 551.4F. 5561.48 4=7. 552.4F. 5562.48 2C .553.4.E. 5563.48 4 554.V7 55=)L.48 -0 7555.4F 555.42 5556.4' 556.48 r C") 31-1YSTC; EDUCATION O Lerr- DIVISION OF INSTRUCTION1971 ADVANCED ;WHAMING PHASE I I - AN(;P:D ;;WIMMETi 5551.101 5561.48 5552.48 5562.48 5553.48 5563.48 5554.48 5564.48 5555.48 5565.48 5556.48 5566.48 PHYSICAL EDUCATION A\IMLN8LE 1315CO?' Written by Dick Gutting for the DIVISIONOF INSTRUCTION Dade County Public Schools Miami, Florida DADE COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD Mr.G. -

Learn About the Skills Taught at Each Level (PDF)

Student: Instructor: LEGEND: *:Critical skill 1: Perfect 2: Mostly 3: Almost 4: With help Skills for Parents there Infant first aid for: airway obstruction, rescue breathing, CPR* Entering and exiting the water safely with your child* Hug position for comfort Back-to-chest position for comfort Face-to-face hold (promotes mimicry)* Dunking* Head-on-shoulder support for back float* Armpit support for front float* Arm stroke to promote reaching and arm movement* Back support for back float* Selection and proper fitting of Personal Floatation Devices (lifejackets)* Skills for Infants 6-18 months Blowing bubbles (promotes breathing out with face in water) Rolling over from front to back (promotes back floating) Supported kicking on front* Supported kicking on back* Reaching/arm stroke (promotes arm movement for locomotion) Introduction to rhythmic breathing (promotes bobbing to safety) Instructor Notes: Registration Recommendation: Date: (*must be at least 3 years old to register for Aquatot 2) Student: Instructor: LEGEND: *:Critical skill 1: Perfect 2: Mostly 3: Almost 4: With help Skills for Parents Child first aid for: airway obstruction, rescue breathing, CPR* Entering and exiting the water safely with your child* Chest support for front float, kicking, and arm stroke* Dunking* Selection and proper fitting of Personal Floatation Devices (lifejackets)* Skills for Toddlers 18 months-3 years Seated entry — scooting in to water Jumping in from side* Independent movement—walking in water* Supported kicking on front* Supported kicking on back* -

An Experimental Testing of Ability and Progress in Swimming Walter J

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1933 An experimental testing of ability and progress in swimming Walter J. Osinski University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Osinski, Walter J., "An experimental testing of ability and progress in swimming" (1933). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 1852. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/1852 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. J883 DATE DUE UNIV. OF MASSACHUSETTS/AMHERST LIBRARY LD M268 1933 0825 "AN EXPERIMENTAL TESTING OP ABILITY AND PROGRESS IN SWIMMING." By Walter J. Osinskl "Thesis Submitted For Degree of Master of Science." Massachusetts State College, Amherst. 1933 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Page Terminology and definitions. •••• • 1 Limi -cation of exporiment • , • • ••«•••«• 5 Limitations of statistics. 4 ORIGIN AND HISTORY OF S'A'IEMING Historical excerpts.... • •••• 5 SURVEY OF SV.T .L ING LITERATURE History of testing in swimr.i5.ng «•••••..« 21 MATERIALS AND METHODS Development of tests* # •,••••••.,,* ..*•*••• 25 Test one. ••,,.».•• » »...•• »•• 26 Test two,... ............ •#••••##• 26 Test throe. •••• •••••#••••••••••••••»•• 27 Test four • ^ Test five 28 Test six, •*,,. ...*•••• • • 28 Method of procedure ,,,«• • • • 29 INTERPRETATION OF DATA Collection of data 34 Chart of entire experimental group,.,. • 37 Leg test of experimental group..... 38 Table I (leg test) 40 Graph I (leg test) 41 Page Collection of data (continuied) • Arm test of experimental group. ••••••• 42 Table II (arm tc st )••...••.«• 44 Graph II (arm test).. -

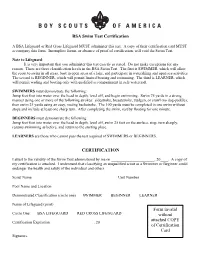

BSA Swim Test Certificate

BSA Swim Test Certification A BSA Lifeguard or Red Cross Lifeguard MUST administer this test. A copy of their certification card MUST accompany this form. Incomplete forms, or absence of proof of certification, will void the Swim Test. Note to Lifeguard: It is very important that you administer this test exactly as stated. Do not make exceptions for any reason. There are three classification levels in the BSA Swim Test. The first is SWIMMER, which will allow the scout to swim in all areas, boat in open areas of a lake, and participate in waterskiing and open sea activities. The second is BEGINNER, which will permit limited boating and swimming. The third is LEARNER, which will permit wading and boating only with qualified accompaniment in safe watercraft. SWIMMERS must demonstrate the following: Jump feet first into water over the head in depth, level off, and begin swimming. Swim 75 yards in a strong manner using one or more of the following strokes: sidestroke, breaststroke, trudgen, or crawl (no dog-paddle); then swim 25 yards using an easy, resting backstroke. The 100 yards must be completed in one swim without stops and include at least one sharp turn. After completing the swim, rest by floating for one minute. BEGINNERS must demonstrate the following: Jump feet first into water over the head in depth, level off, swim 25 feet on the surface, stop, turn sharply, resume swimming as before, and return to the starting place. LEARNERS are those who cannot pass the test required of SWIMMERS or BEGINNERS. CERTIFICATION I attest to the validity of the Swim Test administered by me on ______________________, 20____. -

Basic Rules- the Four Competitive Swimming Strokes Are Freestyle

Basic rules- The four competitive swimming strokes are freestyle, backstroke, breaststroke and butterfly. The combination of all four strokes is called individual medley or IM. In freestyle events, the competitor may swim any stroke. The stroke most commonly used is sometimes called the crawl, which is characterized by the alternate stroking of the arms over the surface of the water surface and an alternating (up-and-down) flutter kick. Backstroke consists of an alternating motion of the arms with a flutter kick while on the back. On turns, swimmers may rotate to the stomach and perform a flip turn after taking 1 freestyle arm pull, and some part of the swimmer must touch the wall. The swimmer must finish on the back. The breaststroke requires simultaneous movements of the arms on the same horizontal plane. The hands are pressed out from in front of the breast in a heart shaped pattern and recovered under or on the surface of the water. The kick is a simultaneous somewhat circular motion similar to the action of a frog. On turns and at the finish, the swimmer must touch the wall with both hands simultaneously at, above or below the water surface. Pull, breathe, kick, glide. Some consider the butterfly to be the most beautiful of the strokes. It features a simultaneous straight arm recovery of the arms over the water combined with an undulating dolphin kick. In the kick, the swimmer must keep both legs together and may not flutter, scissors or use the breaststroke kick. Both hands must touch the wall simultaneously on the turns and the finish. -

Answer the Questions. 1. Explain Your Current Swimming Ability, When Are You Nervous in the Water, When Are You Comfortable, An

History Swimming has been known since prehistoric times. Drawings from the Stone Answer the questions. Age were found in "the cave of swimmers" near Wadi Sora (or Sura) in the southwestern part of Egypt. Written references date from 2000 B.C., including Gilgamesh, the Iliad, the 1. Explain your current Odyssey, the Bible (Ezekiel 47:5, Acts 27:42, Isaiah 25:11), Beowulf, and other sagas. In swimming ability, when 1538 Nicolas Wynman, German professor of languages, wrote the first swimming book, are you nervous in the "Colymbetes". Competitive swimming in Europe started around 1800, mostly using breast- water, when are you stroke. The front crawl, then called the trudgen, was introduced in 1873 by John Arthur comfortable, and can Trudgen, copying it from Native Americans. Swimming was part of the first modern Olym- pic games in 1896 in Athens. In 1902 the trudgen was improved by Richard Cavill, using you swim any of the the flutter kick. In 1908, the world swimming association, Federation Internationale de Na- swimming tation de Amateur (FINA), strokes. was formed. Butterfly was first a variant of breaststroke, until it was accepted as a separate style in 1952. 2. List 5 important rules In 1603 the first national swimming organization was established in Japan. Emperor Go-Yozei of Japan declared that school children should swim. to always follow when The first German swimming club was founded in 1837 in Berlin. A journal mentions swimming. "swimming skates" in France, which may be an early version of a surfboard. Synchronized swimming started in the late 19th century, and the first competition was 3. -

Swimstart Level 5

lesson plans LEVEL FIVE LESSON PLANS Assistant Swim Teacher Award Manual Page 91-106 Pre Assessment: Learners must demonstrate the following skills before beginning Level 5 9 Relaxed Breaststroke timing demonstrating one complete Breaststroke stroke linked to another by a glide 9 Demonstrate 25m Freestyle with controlled arm actions and breathing 9 Demonstrate 25m Backstroke with controlled arm action and relaxed breathing Level Five Learning Intention To develop endurance in Freestyle, Backstroke and Breaststroke swimming with increasingly accurate technique and to increase Water Safety awareness including safe dives. N.B. Lessons 1-3 focus on Freestyle Lesson 4 focus on Sidestroke Lessons 5-6 improve Backstroke efficiency Lessons 7-9 focus on Breaststroke Lesson 10 requires deep water You may need to “pick and choose” different progressions for different group members as they progress. Level Five Learning Outcomes Learners should be able to consistently demonstrate the following criteria: 5.1 25m Sidestroke 5.2 H.E.L.P. 5.3 Clothed Survival 5.4 Group Safety Initiatives 5.5 50m Freestyle 5.6 50m Backstroke 5.7 50m Breaststroke Extra and Optional Unassisted Entries for Deep Water The following lesson plans are suggested programmes for completing the Level Five Objectives. There are many variables to take into consideration. • Diving should only ever be taught in pools deeper than 1.2m unless supported from inside the pool. • Teachers running lessons for 10min may have to omit some activities whereas teachers with 30min lessons may need to be creative and add further activities which enhance or support the activities suggested. • You may at any time extend your swimmers learning. -

Lessons Conversion Chart

Lessons Conversion chart If the swimmer... Register In Previous Level Parent & Is 4 to 12 months old and ready to learn to enjoy the water with a parent Starfish Tot 1 Parent & Is 12 to 24 months old and ready to learn to enjoy the water with a parent Duck Tot 2 Parent & Is 24 to 36 months old and ready to learn to enjoy the water with a parent Sea Turtle Tot 3 3 to 5 years Is 3 to 5 years and just starting out on his/her own in the water (parent Preschool participation for the first five weeks with transition to independent swimming lessons) 1 Can jump into chest-deep water (assisted), get their face wet and Preschool Sea Otter blow bubbles, float on their front and back for 3 sec. assisted 2 Can jump into chest-deep water on their own, submerge and exhale 3 Preschool times, float on their front and back for 3 sec. with a PFD, kick on their Salamander back for 5 m (assisted) 3 Can hold their breath underwater, kick on their front and back for 3 m, Preschool float on their front and back for 5 sec. and jump into deep water while Sunfish wearing a PFD 4 Can recover objects from the bottom in waist deep water, can glide Preschool and kick 5 m independently, float on their back and roll to their front Crocodile then swim 3 m 5 Can kick 7 m on their front, back and side, swim front crawl with a PFD Preschool Whale for 5 m and tread water while wearing a PFD 6 6 to 12 years Can jump independently unto chest-deep water, float of their front Swim Kids 1/ Swimmer 1 and back for 5 sec., glide 3 m and hold their breath underwater Sea Otter, Incomplete Can swim with kick for 5 m, roll laterally front to back and back to front Swim Kids 2/ Swimmer 2 and swim front crawl while wearing a PFD Completed Salamander Complete Can swim with kick for 7 m on front, back and side, tread water for 10 Swim Kids 2/ Swimmer 3 sec. -

Jamestown Community College Master Course

JAMESTOWN COMMUNITY COLLEGE State University of New York INSTITUTIONAL COURSE SYLLABUS Course Title: Individualized Swimming Course Abbreviation and Number: PHE 1710 Credit Hours: 2 Course Type: Lecture/Lab Course Description: Students will be provided instruction in beginning swimming basics. Students will demonstrate skill in drownproofing, elementary backstroke, backstroke, sidestroke, crawl stroke, trudgen stroke, and breaststroke. Improvement in swimming ability and cardiovascular health for all levels of swimmers are the main course objectives. No requisites. Student Learning Outcomes: Students who demonstrate understanding can: 1. Demonstrate proper technique using the freestyle, back, breast, elementary back, butterfly, and side strokes. 2. Develop endurance with distance swimming using the above strokes. 3. Demonstrate basic diving techniques from the pool deck and from the diving board. Topics Covered: Gliding Floating Kicking Free style Back stroke Elementary back stroke Breast stroke Butterfly stroke Side stroke Treading water Diving Turns (open and flip) Breathing techniques Endurance Information for Students Expectations of Students Civility Statement Student Responsibility Statement Academic Integrity Statement Accessibility Services Students who require accommodations to complete the requirements and expectations of this course because of a disability must make their accommodation requests to the Accessibility Services Coordinator. Get Help: JCC & Community Resources Emergency Closing Procedures Course grade is determined by the instructor based on a combination of factors, including but not limited to, homework, quizzes, exams, projects, and participation. Final course grade can be translated into a grade point value according to the following: A=4.0 B+=3.5 B=3 C+=2.5 C=2 D+=1.5 D=1 F=0 Veterans and active duty military personnel with special circumstances (e.g., upcoming deployments, drill requirements, VA appointments) are welcome and encouraged to communicate these to the instructor.