The Global Dimension of RFRA. Gerald L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Council and Participants

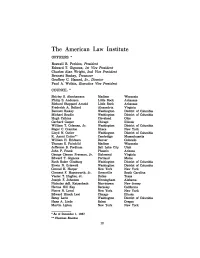

The American Law Institute OFFICERS * Roswell B. Perkins, President Edward T. Gignoux, 1st Vice President Charles Alan Wright, 2nd Vice President Bennett Boskey, Treasurer Geoffrey C. Hazard, Jr., Director Paul A. Wolkin, Executive Vice President COUNCIL * Shirley S. Abrahamson Madison Wisconsin Philip S. Anderson Little Rock Arkansas Richard Sheppard Arnold Little Rock Arkansas Frederick A. Ballard Alexandria Virginia Bennett Boskey Washington District of Columbia Michael Boudin Washington District of Columbia Hugh Calkins Cleveland Ohio Gerhard Casper Chicago Illinois William T. Coleman, Jr. Washington District of Columbia Roger C. Cramton Ithaca New York Lloyd N. Cutler Washington District of Columbia R. Ammi Cutter** Cambridge Massachusetts William H. Erickson Denver Colorado Thomas E. Fairchild Madison Wisconsin Jefferson B. Fordham Salt Lake City Utah John P. Frank Phoenix Arizona George Clemon Freeman, Jr. Richmond Virginia Edward T. Gignoux Portland Maine Ruth Bader Ginsburg Washington District of Columbia Erwin N. Griswold Washington District of Columbia Conrad K. Harper New York New York Clement F. Haynsworth, Jr. Greenville South Carolina Vester T. Hughes, Jr. Dallas Texas Joseph F. Johnston Birmingham Alabama Nicholas deB. Katzenbach Morristown New Jersey Herma Hill Kay Berkeley California Pierre N. Leval New York New York Edward Hirsch Levi Chicago Illinois Betsy Levin Washington District of Columbia Hans A. Linde Salem Oregon Martin Lipton New York New York *As of December 1, 1987 ** Chairman Emeritus OFFICERS AND COUNCIL Robert MacCrate New York New York Hale McCown Lincoln Nebraska Carl McGowan Washington District of Columbia Vincent L. McKusick Portland Maine Robert H. Mundheim Philadelphia Pennsylvania Roswell B. Perkins New York New York Ellen Ash Peters Hartford Connecticut Louis H. -

Why Do Nations Obey International Law?

Review Essay Why Do Nations Obey International Law? The New Sovereignty: Compliance with InternationalRegulatory Agreements. By Abram Chayes" and Antonia Handler Chayes.*" Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995. Pp. xii, 404. $49.95. Fairness in International Law and Institutions. By Thomas M. Franck.- Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995. Pp. 500. $55.00. Harold Hongju Koh Why do nations obey international law? This remains among the most perplexing questions in international relations. Nearly three decades ago, Louis Henkin asserted that "almost all nations observe almost all principles of international law and almost all of their obligations almost all of the time."' Although empirical work since then seems largely to have confirmed this hedged but optimistic description,2 scholars Felix Frankfurter Professor of Law, Emeritus, Harvard Law School ** President, Consensus Building Institute. Murray and Ida Becker Professor of Law; Director. Center for International Studtcs. New York University School of Law. t Gerard C. and Bernice Latrobe Smith Professor of International Law; Director. Orville H, Schell, Jr., Center for International Human Rights, Yale University. Thts Essay sketches arguments to be fleshed out in a forthcoming book, tentatively entitled WHY NATIONS OBEY: A THEORY OF COMPLIANCE WITH INTERNATIONAL LAW. Parts of this Review Essay derive from the 1997 \Vaynflete Lectures. Magdalen College, Oxford University, and a brief book review of the Chayeses volume in 91 Am. J. INT'L L. (forthcoming 1997). 1 am grateful to Glenn Edwards, Jessica Schafer. and Douglas Wolfe for splendid research assistance, and to Bruce Ackerman, Peter Balsam, Geoffrey Brennan. Paul David, Noah Feldman. Roger Hood, Andrew Hurrell, Mark Janis, Paul Kahn, Benedict Kingsbury, Tony Kronran. -

MILITANT LIBERALISM and ITS DISCONTENTS: on the DECOLONIAL ORIGINS of ENDLESS WAR a Dissertation Presented to the Faculty Of

MILITANT LIBERALISM AND ITS DISCONTENTS: ON THE DECOLONIAL ORIGINS OF ENDLESS WAR A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Aaron B Gavin December 2017 © 2017 Aaron B Gavin MILITANT LIBERALISM AND ITS DISCONTENTS: ON THE DECOLONIAL ORIGINS OF ENDLESS WAR Aaron B Gavin, Ph. D. Cornell University 2017 MILITANT LIBERALISM AND ITS DISCONTENTS tells a story about the reinvention of liberalism during the era of decolonization. The dissertation shows how a persistent pattern of militant liberalism came to structure the postwar international order—one where the United States engages in militant action to protect the liberal international order from irredeemable illiberal threats, precisely when its hegemonic influence reaches its limit. While anti-totalitarianism and the war on terror are defining episodes in the development of this pattern, the dissertation argues that it was only liberalism’s encounter with decolonization that made the practice of militant liberalism ideologically coherent and enduring. After shattering the civilizational justifications of nineteenth century liberalism, decolonization provided militant liberals with a unique enemy, the Third World, upon which to distinguish and legitimate their own logic of violence, all while destroying alternative political possibilities arising out of the decolonial process. The dissertation explores these themes through four political thinkers—Isaiah Berlin, Louis Henkin, Frantz Fanon, and Carl Schmitt—and narrates a story about the legitimation of militant liberalism and the eventual rise of its discontents. On the one hand, Berlin and Henkin spoke of Thirdworldism as uniquely threatening: the former arguing that Thirdworldist nationalism often morphed into romantic self-assertion, and the latter claiming that Thirdworldists exploited state sovereignty allowing international terrorism to proliferate unbound. -

JD Columbia Law School 1965 AB Columbia College 1962 Bar

BERNARD H. OXMAN Office: Home: School of Law TEL: 305 284 2293 10 Edgewater Drive (9H) University of Miami FAX: 305 284 6619 Coral Gables, FL 33133 Coral Gables, FL 33124-8087 <[email protected]> TEL: 305 443 9550 Education: J.D. Columbia Law School 1965 A.B. Columbia College 1962 Bar Admissions: District of Columbia, New York Employment: University of Miami School of Law, 1977-present Richard A. Hausler Professor of Law, 2008 to present Professor of Law, 1980-present Director, Maritime Law Program, 1997-present University Faculty Senator, 1996-2008; 2009-2017 Associate Dean, 1987-90 Associate Professor, 1977-80 Subjects taught regularly: conflict of laws, international law, law of the sea, torts AJIL: American Journal of International Law Co-Editor in Chief, 2003-2013 International Decisions Editor, 1998-2003 Board of Editors 1986-present Adjudication, Judge ad hoc, International Court of Justice: Arbitration, Black Sea Maritime Delimitation case (Romania v. Ukraine), Review Panel: 2006-2009 Judge ad hoc, International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea: Land Reclamation case (Malaysia v. Singapore), 2003 Bay of Bengal Maritime Delimitation case (Bangladesh v. Myanmar), 2010-2012 Indian Ocean Maritime Delimitation case (Mauritius/Maldives), 2019- Member, Arbitral Tribunal constituted under Annex VII of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea: Land Reclamation case (Malaysia v. Singapore) (2003-2005) ARA Libertad case (Argentina v. Ghana) (2013) Chair, Review Panel Established under Article 17 and Annex II of the Convention on the Conservation and Management of High Seas Fishery Resources in the South Pacific Ocean Objection of the Russian Federation to CMM 1.01 (2013) Arbitrator, various international commercial arbitrations Counsel for the Philippines in South China Sea arbitration (Phil. -

The Legacy of Louis Henkin: Human Rights in the "Age of Terror" •Fi An

Columbia Law School Scholarship Archive Faculty Scholarship Faculty Publications 2007 The Legacy of Louis Henkin: Human Rights in the "Age of Terror" – An Interview with Sarah H. Cleveland Sarah H. Cleveland Columbia Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, International Law Commons, and the National Security Law Commons Recommended Citation Sarah H. Cleveland, The Legacy of Louis Henkin: Human Rights in the "Age of Terror" – An Interview with Sarah H. Cleveland, 38 COLUM. HUM. RTS. L. REV. 499 (2007). Available at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/1127 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Scholarship Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE LEGACY OF LOUIS HENKIN: HUMAN RIGHTS IN THE "AGE OF TERROR" An Interview with Sarah H. Cleveland* Louis Henkin and the Human Rights Idea What effect has Professor Henkin's work had upon your own thoughts or scholarship in the human rights field? My scholarly work spans the fields of international human rights and U.S. foreign relations law. I am particularly interested in the process by which human rights norms are implemented into domestic legal systems, the role the United States plays in promoting the internalization of human rights norms by other states, and the mechanisms by which the values of the international human rights regime are incorporated into the United States domestic legal system. -

Customary International Law and Human Rights Treaties Are Law of the United States

Michigan Journal of International Law Volume 20 Issue 2 1999 Customary International Law and Human Rights Treaties are Law of the United States Jordan J. Paust University of Houston Law Center Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjil Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Legislation Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Jordan J. Paust, Customary International Law and Human Rights Treaties are Law of the United States, 20 MICH. J. INT'L L. 301 (1999). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjil/vol20/iss2/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Journal of International Law at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CUSTOMARY INTERNATIONAL LAW AND HUMAN RIGHTS TREATIES ARE LAW OF THE UNITED STATES JordanJ. Paust* I. THE FOUNDERS AND PREDOMINANT TRENDS The Founders clearly expected that the customary law of nations was binding, was supreme law, created (among others) private rights and du- ties, and would be applicable in United States federal courts.' For example, at the time of the formation of the Constitution John Jay had written: "Under the national government ... the laws of nations, will always be expounded in one sense ... [and there is] wisdom ... in committing such questions to the jurisdiction and judgment of courts ap- pointed by and responsible only to one national government. -

854-2651 [email protected] COLUMBIA LAW SCHOOL, New

SARAH H. CLEVELAND COLUMBIA LAW SCHOOL 435 W. 116th St. New York, N.Y. 10027 (212) 854-2651 [email protected] PRESENT EMPLOYMENT & PROFESSIONAL ACTIVITIES COLUMBIA LAW SCHOOL, New York, NY. Louis Henkin Professor of Human and Constitutional Rights; Faculty Co-Director of the Human Rights Institute. Teaching and research in international and comparative human rights, international law, foreign affairs and the U.S. Constitution, national security law, and federal civil procedure. Board Member, Columbia University Global Policy Initiative (Since 2013). Board of Directors, Columbia Journal of Transnational Law (Since 2007). UN HUMAN RIGHTS COMMITTEE, Geneva, Switzerland. U.S. independent expert on the United Nations Human Rights Committee, the treaty body overseeing state implementation of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Elected in June 2014 by states parties to the Covenant to serve four-year term commencing Jan. 2015. Special Rapporteur for Follow-up with states regarding concluding observations (2015-2017); Special Rapporteur for New Communications (Since 2017). EUROPEAN COMMISSION FOR DEMOCRACY THROUGH LAW (VENICE COMMISSION). Independent Member on the Council of Europe’s expert advisory body on human rights and rule of law reform. Assist with evaluating the compatibility of national laws and constitutional reforms in Europe, North Africa, Latin America, and elsewhere. Member, and Vice Chair of Sub- Commission on the Rule of Law and Sub-Commission on Federal States (Since 2013). Observer Member (Oct. 2010-April 2013). AMERICAN LAW INSTITUTE, COORDINATING REPORTER, RESTATEMENT (FOURTH) OF THE FOREIGN RELATIONS LAW OF THE UNITED STATES. Co-Coordinating Reporter directing and overseeing preparation of major treatise on U.S. -

Book Reviews

BOOK REVIEWS FOREIGN AFFAIRS AND THE CONSTITUTION.By Louis Henkin*.Mi neola, N.Y.: The Foundation Press, 1972. Pp. 553.$11.50. In reviewing Professor Louis Henkin's book, Foreign Affairs and the Constitution, I am tempted in the manner of those who review books for the New York Review of Books to take offon my own.The title of the book, the timeliness of the subject, and the clear need forexamining the "controlling relevance of the Constitution"' to the conduct of for eign affairs, invites thought and debate. How can one read the title without contemplating the Constitution and the war, for example? The longest, most expensive, and most divisive war of American history has just been concluded.It was made without Congress exercis ing its constitutional right (or perhaps duty) "to declare war," and it ended without a peace treaty.In the meantime the Supreme Court has managed for ten years to avoid a decision as to what has happened to Article I, Section 8 (II) of the Constitution. Professor Henkin states that "[t]he President has power ...to wage in full ...war imposed upon the United States."2 It tests one's imagination, however, to believe that the Vietnam war came about because the President was required to act as commander-in-chief to repel a North Vietnamese attack on the United States. What has happened to the power of Congress to declare war? Surely the United Nations Charter with its principle that all members "shall settle their international disputes by peaceful means"3 did not amend Congress's constitutional power to declare war. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE, Vol. 156, Pt. 12 November 17, 2010

November 17, 2010 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE, Vol. 156, Pt. 12 17719 REMEMBERING LOUIS HENKIN Henkin, and we at the Commission on service of Raymond M. Kight, who is ∑ Mr. CARDIN. Mr. President, today I Security and Cooperation in Europe the longest-serving elected sheriff of wish to commemorate the life of Louis join that mourning. Our deepest and Montgomery County. Ray Kight was an Henkin. most sincere condolences and prayers Army veteran when he joined the As chairman of the Commission on go out to his family and friends. He Montgomery County Police Depart- Security and Cooperation in Europe, I shall be missed.∑ ment in 1963. He was sworn in as dep- wish to honor the memory of Professor f uty sheriff in 1967 and was elected sher- iff in 1986. Louis Henkin, known to many as the RECOGNIZING HOWARD father of human rights law, who passed During his tenure, Sheriff Kight COMMUNITY COLLEGE away last month. He was born Eliezer transitioned the office into a modern, Henkin on November 11, 1917, in mod- ∑ Mr. CARDIN. Mr. President, today I professional law enforcement agency. ern-day Belarus. He was the son of recognize the 40th anniversary of How- In addition to the traditional role in Rabbi Yosef Eliyahu Henkin, an au- ard Community College in Howard the service of legal process, protecting thority in Jewish law. Louis, as he County, MD. In 1970, Howard Commu- the courts, transporting prisoners and later became known, came to the nity College began with 1 building and apprehending fugitives, the Sheriff’s United States at the age of five in 1923. -

Lifting Our Veil of Ignorance: Culture, Constitutionalism, and Women's

Fordham Law School FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History Faculty Scholarship 2005 Lifting Our Veil of Ignorance: Culture, Constitutionalism, and Women's Human Rights in Post-September 11 America Catherine Powell Fordham University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Human Rights Law Commons Recommended Citation Catherine Powell, Lifting Our Veil of Ignorance: Culture, Constitutionalism, and Women's Human Rights in Post-September 11 America , 57 Hastings L.J. 331 (2005-2006) Available at: http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/faculty_scholarship/410 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lifting Our Veil of Ignorance: Culture, Constitutionalism, and Women's Human Rights in Post-September i i America CATHERINE POWELL* INTRODUCTION While we live in an Age of Rights,' culture continues to be a major challenge to the human rights project. During the drafting of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR)2 in the 194os and during the Cold War era, the periodic disputes that erupted over civil and political rights in contrast to economic, social and cultural rights could be read either explicitly or implicitly as a cultural debate.' Some scholars and commentators claim that with the collapse of the Cold War and in the aftermath of the September ii terrorist attacks, the clash today is even more explicitly a cultural one-between Western and other cultures.4 Despite attempts by President George W. -

Brief of Louis Henkin, Harold Hongju Koh, and Michael H. Posner As Amici Curiae in Support of Respondents

No. 03-1027 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States DONALD RUMSFELD, Petitioner, v. JOSE PADILLA and DONNA R. NEWMAN as Next Friend of Jose Padilla, Respondents. ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT BRIEF OF LOUIS HENKIN, HAROLD HONGJU KOH, AND MICHAEL H. POSNER AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS DEBORAH PEARLSTEIN DONALD FRANCIS DONOVAN HUMAN RIGHTS FIRST* (Counsel of Record) 100 Maryland Avenue, N.E. CARL MICARELLI Suite 500 J. PAUL OETKEN Washington, DC 20002-5625 ALEXANDER K.A. GREENAWALT Telephone: (202) 547-5692 JIHEE GILLIAN SUH DEBEVOISE & PLIMPTON LLP * Formerly the Lawyers Committee 919 Third Avenue for Human Rights. New York, NY 10022-3916 Telephone: (212) 909-6000 Counsel for Amici Curiae Louis Henkin, Harold Hongju Koh, and Michael H. Posner TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS........................................................ i TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.................................................ii INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE.......................................... 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .............................................. 2 ARGUMENT.......................................................................... 5 I. THE EXECUTIVE IS CONSTRAINED BY LAW EVEN IN TIMES OF WAR....................... 5 A. The Constitution Does Not Confer Limitless Powers on the President Even in Times of War.......................................... 5 B. This Court Has Recognized that the Law Applies in Times of War........................... 10 C. The Law of War, As Defined by Applicable Statutes, Treaties, and Customary Law, Imposes Limits on Detention in Times of Armed Conflict. .............................................................. 18 II. THE EXECUTIVE’S DETENTION OF PADILLA IS UNLAWFUL..................................... 22 CONCLUSION.................................................................... 28 (i) ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Cases Cramer v. United States, 325 U.S. 1 (1945) ......................................................15, 21 United States v. Curtiss-Wright Export Co., 299 U.S. -

Is International Law Really State Law?

COMMENTARY IS INTERNATIONAL LAW REALLY STATE LAW? Harold Hangju Koh* Revisionist scholars have recently challenged the hornbook rule that United States federal courts shall determine questions of customary international law as federal law. The revisionists claim that the traditional rule violates constitutional history and doctrine, and offends fundamental principles of separation of powers, federalism, and democracy. Professor Koh rebuts the revisionist challenge, applying each of the revisionists' own stated criteria. He demonstrates that the lawful and sensible practice of treating international law as federal law should be left undisturbed by both the political and judicial branches. How should we understand the following passages? [W]e are constrained to make it clear that an issue concerned with a basic choice regarding the competence and function of the Judiciary and the National Executive in ordering our relationships with other members of the international community must be treated exclusively as an aspect of federal law.' Customary international law is federal law, to be enunciated authorita- tively by the federal courts.2 International human rights cases predictably raise legal issues - such as interpretationsof internationallaw - that are matters of Federal common law and within the particular expertise of Federal courts.3 Taking these passages at face value, most readers would under- stand them to mean just what they say: judicial determinations of in- ternational law - including international human rights law - are matters of federal law. That these three declarations emanate from the * Gerard C. and Bernice Latrobe Smith Professor of International Law and Director, Orville H. Schell, Jr. Center for International Human Rights, Yale Law School.