Is International Law Really State Law?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Council and Participants

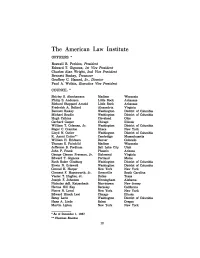

The American Law Institute OFFICERS * Roswell B. Perkins, President Edward T. Gignoux, 1st Vice President Charles Alan Wright, 2nd Vice President Bennett Boskey, Treasurer Geoffrey C. Hazard, Jr., Director Paul A. Wolkin, Executive Vice President COUNCIL * Shirley S. Abrahamson Madison Wisconsin Philip S. Anderson Little Rock Arkansas Richard Sheppard Arnold Little Rock Arkansas Frederick A. Ballard Alexandria Virginia Bennett Boskey Washington District of Columbia Michael Boudin Washington District of Columbia Hugh Calkins Cleveland Ohio Gerhard Casper Chicago Illinois William T. Coleman, Jr. Washington District of Columbia Roger C. Cramton Ithaca New York Lloyd N. Cutler Washington District of Columbia R. Ammi Cutter** Cambridge Massachusetts William H. Erickson Denver Colorado Thomas E. Fairchild Madison Wisconsin Jefferson B. Fordham Salt Lake City Utah John P. Frank Phoenix Arizona George Clemon Freeman, Jr. Richmond Virginia Edward T. Gignoux Portland Maine Ruth Bader Ginsburg Washington District of Columbia Erwin N. Griswold Washington District of Columbia Conrad K. Harper New York New York Clement F. Haynsworth, Jr. Greenville South Carolina Vester T. Hughes, Jr. Dallas Texas Joseph F. Johnston Birmingham Alabama Nicholas deB. Katzenbach Morristown New Jersey Herma Hill Kay Berkeley California Pierre N. Leval New York New York Edward Hirsch Levi Chicago Illinois Betsy Levin Washington District of Columbia Hans A. Linde Salem Oregon Martin Lipton New York New York *As of December 1, 1987 ** Chairman Emeritus OFFICERS AND COUNCIL Robert MacCrate New York New York Hale McCown Lincoln Nebraska Carl McGowan Washington District of Columbia Vincent L. McKusick Portland Maine Robert H. Mundheim Philadelphia Pennsylvania Roswell B. Perkins New York New York Ellen Ash Peters Hartford Connecticut Louis H. -

Why Do Nations Obey International Law?

Review Essay Why Do Nations Obey International Law? The New Sovereignty: Compliance with InternationalRegulatory Agreements. By Abram Chayes" and Antonia Handler Chayes.*" Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995. Pp. xii, 404. $49.95. Fairness in International Law and Institutions. By Thomas M. Franck.- Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995. Pp. 500. $55.00. Harold Hongju Koh Why do nations obey international law? This remains among the most perplexing questions in international relations. Nearly three decades ago, Louis Henkin asserted that "almost all nations observe almost all principles of international law and almost all of their obligations almost all of the time."' Although empirical work since then seems largely to have confirmed this hedged but optimistic description,2 scholars Felix Frankfurter Professor of Law, Emeritus, Harvard Law School ** President, Consensus Building Institute. Murray and Ida Becker Professor of Law; Director. Center for International Studtcs. New York University School of Law. t Gerard C. and Bernice Latrobe Smith Professor of International Law; Director. Orville H, Schell, Jr., Center for International Human Rights, Yale University. Thts Essay sketches arguments to be fleshed out in a forthcoming book, tentatively entitled WHY NATIONS OBEY: A THEORY OF COMPLIANCE WITH INTERNATIONAL LAW. Parts of this Review Essay derive from the 1997 \Vaynflete Lectures. Magdalen College, Oxford University, and a brief book review of the Chayeses volume in 91 Am. J. INT'L L. (forthcoming 1997). 1 am grateful to Glenn Edwards, Jessica Schafer. and Douglas Wolfe for splendid research assistance, and to Bruce Ackerman, Peter Balsam, Geoffrey Brennan. Paul David, Noah Feldman. Roger Hood, Andrew Hurrell, Mark Janis, Paul Kahn, Benedict Kingsbury, Tony Kronran. -

The Global Dimension of RFRA. Gerald L

University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository Constitutional Commentary 1997 The Global Dimension of RFRA. Gerald L. Neuman Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/concomm Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Neuman, Gerald L., "The Global Dimension of RFRA." (1997). Constitutional Commentary. 375. https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/concomm/375 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Minnesota Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Constitutional Commentary collection by an authorized administrator of the Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE GLOBAL DIMENSION OF RFRA Gerald L. Neuman* A multi-faceted controversy is currently raging over the con stitutionality of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993 (RFRA),t the federal legislative response to the Supreme Court's decision in Employment Division v. Smith.z In Smith, the Supreme Court eliminated most constitutional claims to religious exemption from generally applicable laws, abandoning a prior practice of subjecting such claims (verbally at least) to a compel ling interest test. The majority asserted that the Free Exercise Clause does not require state or federal governments to accom modate conscientious objectors to compliance with generally ap plicable laws. Congress, in turn, emphasized that "laws 'neutral' toward religion may burden religious exercise as surely as laws intended to interfere with religious exercise," and acted to "re store the compelling interest test" as a matter of statutory right.3 Congress's authority to enact such a statute, particularly as applied to generally applicable laws of the states, has been dis puted. -

MILITANT LIBERALISM and ITS DISCONTENTS: on the DECOLONIAL ORIGINS of ENDLESS WAR a Dissertation Presented to the Faculty Of

MILITANT LIBERALISM AND ITS DISCONTENTS: ON THE DECOLONIAL ORIGINS OF ENDLESS WAR A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Aaron B Gavin December 2017 © 2017 Aaron B Gavin MILITANT LIBERALISM AND ITS DISCONTENTS: ON THE DECOLONIAL ORIGINS OF ENDLESS WAR Aaron B Gavin, Ph. D. Cornell University 2017 MILITANT LIBERALISM AND ITS DISCONTENTS tells a story about the reinvention of liberalism during the era of decolonization. The dissertation shows how a persistent pattern of militant liberalism came to structure the postwar international order—one where the United States engages in militant action to protect the liberal international order from irredeemable illiberal threats, precisely when its hegemonic influence reaches its limit. While anti-totalitarianism and the war on terror are defining episodes in the development of this pattern, the dissertation argues that it was only liberalism’s encounter with decolonization that made the practice of militant liberalism ideologically coherent and enduring. After shattering the civilizational justifications of nineteenth century liberalism, decolonization provided militant liberals with a unique enemy, the Third World, upon which to distinguish and legitimate their own logic of violence, all while destroying alternative political possibilities arising out of the decolonial process. The dissertation explores these themes through four political thinkers—Isaiah Berlin, Louis Henkin, Frantz Fanon, and Carl Schmitt—and narrates a story about the legitimation of militant liberalism and the eventual rise of its discontents. On the one hand, Berlin and Henkin spoke of Thirdworldism as uniquely threatening: the former arguing that Thirdworldist nationalism often morphed into romantic self-assertion, and the latter claiming that Thirdworldists exploited state sovereignty allowing international terrorism to proliferate unbound. -

JD Columbia Law School 1965 AB Columbia College 1962 Bar

BERNARD H. OXMAN Office: Home: School of Law TEL: 305 284 2293 10 Edgewater Drive (9H) University of Miami FAX: 305 284 6619 Coral Gables, FL 33133 Coral Gables, FL 33124-8087 <[email protected]> TEL: 305 443 9550 Education: J.D. Columbia Law School 1965 A.B. Columbia College 1962 Bar Admissions: District of Columbia, New York Employment: University of Miami School of Law, 1977-present Richard A. Hausler Professor of Law, 2008 to present Professor of Law, 1980-present Director, Maritime Law Program, 1997-present University Faculty Senator, 1996-2008; 2009-2017 Associate Dean, 1987-90 Associate Professor, 1977-80 Subjects taught regularly: conflict of laws, international law, law of the sea, torts AJIL: American Journal of International Law Co-Editor in Chief, 2003-2013 International Decisions Editor, 1998-2003 Board of Editors 1986-present Adjudication, Judge ad hoc, International Court of Justice: Arbitration, Black Sea Maritime Delimitation case (Romania v. Ukraine), Review Panel: 2006-2009 Judge ad hoc, International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea: Land Reclamation case (Malaysia v. Singapore), 2003 Bay of Bengal Maritime Delimitation case (Bangladesh v. Myanmar), 2010-2012 Indian Ocean Maritime Delimitation case (Mauritius/Maldives), 2019- Member, Arbitral Tribunal constituted under Annex VII of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea: Land Reclamation case (Malaysia v. Singapore) (2003-2005) ARA Libertad case (Argentina v. Ghana) (2013) Chair, Review Panel Established under Article 17 and Annex II of the Convention on the Conservation and Management of High Seas Fishery Resources in the South Pacific Ocean Objection of the Russian Federation to CMM 1.01 (2013) Arbitrator, various international commercial arbitrations Counsel for the Philippines in South China Sea arbitration (Phil. -

The Legacy of Louis Henkin: Human Rights in the "Age of Terror" •Fi An

Columbia Law School Scholarship Archive Faculty Scholarship Faculty Publications 2007 The Legacy of Louis Henkin: Human Rights in the "Age of Terror" – An Interview with Sarah H. Cleveland Sarah H. Cleveland Columbia Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, International Law Commons, and the National Security Law Commons Recommended Citation Sarah H. Cleveland, The Legacy of Louis Henkin: Human Rights in the "Age of Terror" – An Interview with Sarah H. Cleveland, 38 COLUM. HUM. RTS. L. REV. 499 (2007). Available at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/1127 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Scholarship Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE LEGACY OF LOUIS HENKIN: HUMAN RIGHTS IN THE "AGE OF TERROR" An Interview with Sarah H. Cleveland* Louis Henkin and the Human Rights Idea What effect has Professor Henkin's work had upon your own thoughts or scholarship in the human rights field? My scholarly work spans the fields of international human rights and U.S. foreign relations law. I am particularly interested in the process by which human rights norms are implemented into domestic legal systems, the role the United States plays in promoting the internalization of human rights norms by other states, and the mechanisms by which the values of the international human rights regime are incorporated into the United States domestic legal system. -

Customary International Law and Human Rights Treaties Are Law of the United States

Michigan Journal of International Law Volume 20 Issue 2 1999 Customary International Law and Human Rights Treaties are Law of the United States Jordan J. Paust University of Houston Law Center Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjil Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Legislation Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Jordan J. Paust, Customary International Law and Human Rights Treaties are Law of the United States, 20 MICH. J. INT'L L. 301 (1999). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjil/vol20/iss2/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Journal of International Law at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CUSTOMARY INTERNATIONAL LAW AND HUMAN RIGHTS TREATIES ARE LAW OF THE UNITED STATES JordanJ. Paust* I. THE FOUNDERS AND PREDOMINANT TRENDS The Founders clearly expected that the customary law of nations was binding, was supreme law, created (among others) private rights and du- ties, and would be applicable in United States federal courts.' For example, at the time of the formation of the Constitution John Jay had written: "Under the national government ... the laws of nations, will always be expounded in one sense ... [and there is] wisdom ... in committing such questions to the jurisdiction and judgment of courts ap- pointed by and responsible only to one national government. -

854-2651 [email protected] COLUMBIA LAW SCHOOL, New

SARAH H. CLEVELAND COLUMBIA LAW SCHOOL 435 W. 116th St. New York, N.Y. 10027 (212) 854-2651 [email protected] PRESENT EMPLOYMENT & PROFESSIONAL ACTIVITIES COLUMBIA LAW SCHOOL, New York, NY. Louis Henkin Professor of Human and Constitutional Rights; Faculty Co-Director of the Human Rights Institute. Teaching and research in international and comparative human rights, international law, foreign affairs and the U.S. Constitution, national security law, and federal civil procedure. Board Member, Columbia University Global Policy Initiative (Since 2013). Board of Directors, Columbia Journal of Transnational Law (Since 2007). UN HUMAN RIGHTS COMMITTEE, Geneva, Switzerland. U.S. independent expert on the United Nations Human Rights Committee, the treaty body overseeing state implementation of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Elected in June 2014 by states parties to the Covenant to serve four-year term commencing Jan. 2015. Special Rapporteur for Follow-up with states regarding concluding observations (2015-2017); Special Rapporteur for New Communications (Since 2017). EUROPEAN COMMISSION FOR DEMOCRACY THROUGH LAW (VENICE COMMISSION). Independent Member on the Council of Europe’s expert advisory body on human rights and rule of law reform. Assist with evaluating the compatibility of national laws and constitutional reforms in Europe, North Africa, Latin America, and elsewhere. Member, and Vice Chair of Sub- Commission on the Rule of Law and Sub-Commission on Federal States (Since 2013). Observer Member (Oct. 2010-April 2013). AMERICAN LAW INSTITUTE, COORDINATING REPORTER, RESTATEMENT (FOURTH) OF THE FOREIGN RELATIONS LAW OF THE UNITED STATES. Co-Coordinating Reporter directing and overseeing preparation of major treatise on U.S. -

The Constitution in the Supreme Court: Civil War and Reconstruction, 1865-1873 David P

The Constitution in the Supreme Court: Civil War and Reconstruction, 1865-1873 David P. Curriet The appointment of Salmon P. Chase as Chief Justice in De- cember 1864, like that of his predecessor in 1836, marked the be- ginning of a new epoch in the Court's history. Not only had the Civil War altered the legal landscape dramatically; Chase was to preside over an essentially new complement of Justices. Of those who had sat more than a few years with Chief Justice Roger Ta- ney, only Samuel Nelson and Robert Grier were to remain for a significant time. With them were six newcomers appointed be- tween 1858 and 1864, five of them by Abraham Lincoln and four of them Republicans: Nathan Clifford, Noah H. Swayne, Samuel F. Miller, David Davis, Stephen J. Field, and Chase himself. These eight Justices were to sit together through most of the period until Chase's death in 1873. Taney's longtime colleagues James M. Wayne and John Catron were gone by 1867; William Strong, Jo- seph P. Bradley, and Ward Hunt, appointed at the end of Chase's tenure, played relatively minor roles. The work of the Chase period was largely done by eight men.1 Chase was Chief Justice for less than nine years, but his ten- ure was a time of important constitutional decisions. Most of the significant cases fall into three categories. The best known cases, which serve as the subject of this article, involve a variety of ques- tions arising out of the Civil War itself. Less dramatic but of com- parable impact on future litigation and of comparable jurispruden- tial interest were a number of decisions determining the inhibitory effect of the commerce clause on state legislation. -

The Fourteenth Amendment and the Unconstitutionality of Secession

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron Akron Law Review Akron Law Journals June 2015 The ourF teenth Amendment and the Unconstitutionality of Secession Daniel A. Farber Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Follow this and additional works at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Fourteenth Amendment Commons Recommended Citation Farber, Daniel A. (2012) "The ourF teenth Amendment and the Unconstitutionality of Secession," Akron Law Review: Vol. 45 : Iss. 2 , Article 6. Available at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview/vol45/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Akron Law Journals at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The nivU ersity of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Akron Law Review by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Farber: The Fourteenth Amendment 12- FARBER_MACRO.DOCM 6/13/2012 3:42 PM THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT AND THE UNCONSTITUTIONALITY OF SECESSION Daniel A. Farber∗ I. Introduction ...................................................................... 479 II. Antebellum Conceptions of Citizenship and the Nature of the Union ...................................................................... 484 A. Secession and the Nature of the Union ...................... 485 B. Federalism -

Annual Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS ANNUAL REPORT July 1,1998 - June 30,1999 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 861-•1789 TTele . (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www.cfr.org E-mail communications@cfr. org Officers and Directors, 1999–2000 Officers Directors Term Expiring 2004 Peter G. Peterson Term Expiring 2000 John Deutch Chairman of the Board Jessica P.Einhorn Carla A. Hills Maurice R. Greenberg Louis V. Gerstner Jr. Robert D. Hormats* Vice Chairman Maurice R. Greenberg William J. McDonough* Leslie H. Gelb Theodore C. Sorensen President George J. Mitchell George Soros* Michael P.Peters Warren B. Rudman Senior Vice President, Chief Operating Term Expiring 2001 Leslie H. Gelb Officer, and National Director ex officio Lee Cullum Paula J. Dobriansky Vice President, Washington Program Mario L. Baeza Honorary Officers David Kellogg Thomas R. Donahue and Directors Emeriti Vice President, Corporate Affairs, Richard C. Holbrooke Douglas Dillon and Publisher Peter G. Peterson† Caryl P.Haskins Lawrence J. Korb Robert B. Zoellick Charles McC. Mathias Jr. Vice President, Studies David Rockefeller Term Expiring 2002 Elise Carlson Lewis Honorary Chairman Vice President, Membership Paul A. Allaire and Fellowship Affairs Robert A. Scalapino Roone Arledge Abraham F. Lowenthal Cyrus R.Vance John E. Bryson Vice President Glenn E. Watts Kenneth W. Dam Anne R. Luzzatto Vice President, Meetings Frank Savage Janice L. Murray Laura D’Andrea Tyson Vice President and Treasurer Term Expiring 2003 Judith Gustafson Secretary Peggy Dulany Martin S. -

Title of the Thesis

From Convention to Classroom: The Long Road to Human Rights Education Paula Gerber Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Law School The University of Melbourne January 2008 Abstract A core function of the United Nations over the past six decades has been the promotion and protection of human rights. In pursuit of this goal, the UN General Assembly has adopted numerous human rights treaties covering a vast array of rights. Because it has the highest number of ratifications, the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CROC), is often lauded as the most successful of all the human rights treaties. Although the breadth and depth of human rights treaties is impressive, the amount of research into their effectiveness is not. Very little scholarship has been undertaken to evaluate the extent to which human rights treaties are being complied with by countries that have ratified them and whether ratification of a human rights treaty has a positive impact on the human rights situation within a State Party’s jurisdiction. The research that has been undertaken has been largely quantitative and limited to studies of compliance with civil and political rights. This thesis builds on this limited scholarship by qualitatively analysing the ‘compliance’ levels of two States, Australia and the United States, with the norm in Article 29(1) of CROC relating to human rights education (HRE). Although the United States has not ratified CROC, it was selected as one of the case studies for this research in order to enable comparison to be made between HRE in a State that has ratified CROC, and a State that has not, thereby shedding light on whether ratification of a human rights treaty makes a difference.