OPEN FORUM 'With Many Hands, the Burden Isn't Heavy": Creole

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Haiti Thirst for Justice

September 1996 Vol. 8, No. 7 (B) HAITI THIRST FOR JUSTICE A Decade of Impunity in Haiti I. SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS...........................................................................................................................2 II. IMPUNITY SINCE THE FALL OF THE DUVALIER FAMILY DICTATORSHIP ...........................................................7 The Twenty-Nine Year Duvalier Dictatorship Ends with Jean-Claude Duvalier's Flight, February 7, 1986.................7 The National Governing Council, under Gen. Henri Namphy, Assumes Control, February 1986 ................................8 Gen. Henri Namphy's Assumes Full Control, June 19, 1988.........................................................................................9 Gen. Prosper Avril Assumes Power, October 1988.....................................................................................................10 President Ertha Pascal Trouillot Takes Office, March 13, 1990 .................................................................................11 Jean-Bertrand Aristide Assumes Office as Haiti's First Democratically Elected President, February 7, 1991............12 Gen. Raul Cédras, Lt. Col. Michel François, and Gen. Phillippe Biamby Lead a Coup d'Etat Forcing President Aristide into Exile, Sept. 30, 1991 ...................................................................................13 III. IMPUNITY FOLLOWING PRESIDENT JEAN-BERTRAND ARISTIDE'S RETURN ON OCTOBER 15, 1994, AND PRESIDENT RENÉ PRÉVAL'S INAUGURATION ON FEBRUARY 7, 1996..............................................16 -

Won't Buy All Books

The Courier Volume 4 Issue 31 Article 1 6-4-1971 The Courier, Volume 4, Issue 31, June 4, 1971 Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.cod.edu/courier This Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the College Publications at DigitalCommons@COD. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Courier by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@COD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. First CD nursing Nearly 700 class graduates to graduate The fourth commencement College of DuPage will graduate Berg, college president, was the exercises of College of DuPage will its first class of nurses at next speaker. be Friday evening, June 11, at 7:45 week’s commencement exercises. Mrs. Santucci said she is urging in the college gym. About 650 Twenty eight nurses, one of them the students to work in general Associate degrees and about 50 male, will graduate and after hospitals for wide experience certificates in various technologies taking a state board examination before specializing. will be awarded. qualify as registered nurses. The class that was “pinned” Dr. Rodney Berg, college Mary Ann Santucci, chairman of includes: president, will introduce the stage the nursing program, presented Susan Altorfer, Carol Beechler, party and the speakers of the pins to the class at a meeting May Betty Black, Patricia Crandall, evening. Thomas Biggs, president 16 in the Gymnasium. Dr. Rodney Betty Crim, Donna Dorrough, of the Associated Student Body, Noreen Ehlenburg, Gloria Ellis, will make remarks. Phyllis Foster, Denise Gilman, The main speaker of the evening Diane Hastings, Carol Jenkins, will be Dr. -

Reconstructing Democracy

Reconstructing Democracy Joint Report of Independent Electoral Monitors of Haiti’s November 28, 2010 Election Let Haiti Live Organizations listed indicate participants in November 28th observer delegation Table of Contents Executive Summary I. Introduction II. Credibility and Timing of November 28, 2010 Election The CEP and Exclusions Without Justification Inadequate Time to Prepare Election Election in the Midst of Crises The Role of MINUSTAH III. Observations of the Independent Monitors IV. Responses from Haiti and the International Community Haitian Civil Society The OAS and CARICOM The United Nations The United States Canada V. Conclusions APPENDICES A. Additional Analysis of the Electoral Law B. Detailed Observation from the Institute for Justice and Democracy in Haiti Team C. Summary of Election Day 11/28/10, The Louisiana Justice Institute, Jacmel D. Observations from Nicole Lazarre, The Louisiana Justice Institute, in Port-au-Prince E. Observations from Alexander Main, Center for Economic and Policy Research F. Observations from Clay Kilgore, Kledev G. Voices of Haiti: In Pursuit of the Undemocratic, Mark Snyder, International Action Ties H. U.S. Will Pay for Haitian Vote Fraud, Brian Concannon and Jeena Shah, IJDH Executive Summary The first round of Haiti’s presidential and legislative election was held on November 28, 2010 in particularly inauspicious conditions. Over one million people who lost their homes in the earthquake were still living in appalling conditions, in makeshift camps, in and around Port-au- Prince. A cholera epidemic that had already claimed over two thousand lives was raging throughout the country. Finally, the election was being organized by a provisional electoral authority council that was hand-picked by President Préval and widely distrusted. -

HAITI COUNTRY READER TABLE of CONTENTS Merritt N. Cootes 1932

HAITI COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS Merritt N. Cootes 1932 Junior Officer, Port-au-Prince 1937-1940 Vice Consul, Port-au-Prince Henry L. T. Koren 1948-1951 Administrative Officer, Port-au-Prince Slator Clay Blackiston, Jr. 1950-1952 Economic Officer, Port-au-Prince Milton Barall 1954-1956 Deputy Chief of Mission, Port-au-Prince Raymond E. Chambers 1955-1957 Deputy Director of Binational Center, USIA, Port-au-Prince Edmund Murphy 1961-1963 Public Affairs Office, USIA, Port-au-Prince Jack Mendelsohn 1964-1966 Consular/Political Officer, Port-au-Prince Claude G. Ross 1967-1969 Ambassador, Haiti John R. Burke 1970-1972 Deputy Chief of Mission, Port-au-Prince Harry E. Mattox 1970-1973 Economic Officer, Port-au-Prince Robert S. Steven 1971-1973 Special Assistant to Under Secretary of Management, Department of State, Washington, DC Jon G. Edensword 1972-1973 Visa Officer, Port-au-Prince Michael Norton 1972-1980 Radio News Reporter, Haiti Keith L. Wauchope 1973-1974 State Department Haiti Desk Officer, Washington, DC Scott Behoteguy 1973-1977 Mission Director, USAID, Haiti Wayne White 1976-1978 Consular Officer, Port-au-Prince Lawrence E. Harrison 1977-1979 USAID Mission Director, Port-au-Prince William B. Jones 1977-1980 Ambassador, Haiti Anne O. Cary 1978-1980 Economic/Commercial Officer, Port-au- Prince Ints M. Silins 1978-1980 Political Officer, Port-au-Prince Scott E. Smith 1979-1981 Head of Project Development Office, USAID, Port-au-Prince Henry L. Kimelman 1980-1981 Ambassador, Haiti David R. Adams 1981-1984 Mission Director, USAID, Haiti Clayton E. McManaway, Jr. 1983-1986 Ambassador, Haiti Jon G. -

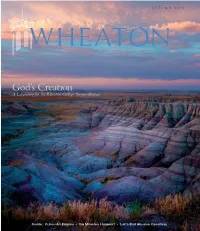

God's Creation and Learn More ABET Accredited Schools Including University of Illinois at Urbana- About Him

AUTUMN 2013 WHEATON God’s Creation A Laboratory for the Wheaton College Science Station Inside: Cuba––An Enigma • Do Miracles Happen? • Let’s End Abusive Coaching 133858_FC,IFC,01,BC.indd 1 8/4/13 4:31 PM Wheaton College serves Jesus Christ and advances His Kingdom through excellence in liberal arts and graduate programs that educate the whole person to build the church and benefit society worldwide. volume 16 issue 3 A u T umN 2013 6 14 ALUMNI NEWS DEPARTMENTS 34 A Word with Alumni 2 Letters From the director of alumni relations 4 News 35 Wheaton Alumni Association News Sports Association news and events 10 56 Authors 40 Alumni Class News Books by Wheaton’s faculty; thoughts on grieving from Luke Veldt ’84. Cover photo: The Badlands of South Dakota is a destination for study and 58 Readings discovery for Wheaton students, and is in close proximity to their base Excerpts from the 2013 commencement address camp, the Wheaton College Science Station (see story, p.6). The geology by Rev. Francis Chan. program’s biannual field camp is a core academic requirement that gives majors experience in field methods as they participate in mapping 60 Faculty Voice exercises based on the local geological features of the Black Hills region. On field trips to the Badlands, environmental science and biology majors Dr. Michael Giuliano, head coach of men’s soccer learn about the arid grassland ecosystem and observe its unique plants and adjunct professor of communication studies, and animals. Geology students learn that the multicolored sediment layers calls for an end to abusive coaching. -

My Experience Working with the UN, the OAS, IFES, IRI, USAID, and Other International Organizations on Haiti’S Elections, from 1987 to 2000 by Jean Paul Poirier

My Experience Working with the UN, the OAS, IFES, IRI, USAID, and other International Organizations on Haiti’s Elections, from 1987 to 2000 by Jean Paul Poirier Historical Context Haiti has the distinction for defeating the Napoleonic Armies1 and for being the first black republic.2 Although this was a historic undertaking, it led to many difficulties in the develop- ment of the burgeoning nation.3 That the war against France virtually destroyed the capital Port-au-Prince, as well as the infrastructure of the economy, which was mostly oriented in providing sugar and other agricultural goods to France, was a crippling consequence.4 The fact that most developed nations boycotted the new nation in its early stages5 also contributed to the slow development of the new republic. As Hauge stated, “A symbiotic relationship developed between the two most powerful groups in Haiti, the military and the merchant elites.” He further added, “By 1938 Haiti had transferred more than 30 million Francs to France.” The alliance between the military and the merchant elites was countered in 1957 by Dr. François Duvalier coming to power, and retained his power by creating his own personal armed militia, the feared Tonton Macoutes.6 This violent and brutal force assisted Duvalier in maintaining a reign of terror, depleting the country of many of its elites who took refuge in the U.S., Canada,7 and France. At Duvalier’s death in 1971,8 he was succeeded by his son Jean Claude, aged nineteen years old. As Wenche brought forth, “Jean Claude reestablished the traditional relationship between the state and Haiti’s elites and in doing this lost support of the old Duvalierists.” Although Haiti gained considerable economic support during Jean Claude’s tenure, he lost his grasp on power though a number of factors, including the development of popular and peasant organizations in the 1980s,9 It all came to a head when Pope Jean Paul II’s famous phrase “Il faut que sa change,”10 rocked Duvalier’s regime to its core. -

Wheaton Athletes Worldwide

WH E A WHEATON T O N 21 INNOVATORS | COMMUNISM TO CHRIST | JIM HEIMBACH '78 | STUDENT DEBT REAR ADMIRAL R. TIMOTHY ZIEMER '68, P.46 USN (RET.) VOLUME 2015 ISSUE 18 3 // // AUTUMN 2015AUTUMN 21 Innovators in the 21st Century WHEATON.EDU/MAGAZINE Student Debt: Why It’s Worth It From Communism to Christ KNOW A STUDENT WHO BELONGS AT WHEATON? TELL US! As alumni and friends of Wheaton, you play a critical role in helping us identify the best and brightest students to recruit to the College. You have a unique understanding of Wheaton and can easily identify the type of students who will take full advantage of the Wheaton College experience. We value your opinion and invite you to join us in the recruit- ment process. Please send contact information of potential students you believe will thrive in Wheaton’s rigorous and Christ-centered academic environment. We will take the next step to connect with them and begin the process. 800.222.2419 x0 wheaton.edu/refer VOLUME 18 // ISSUE 3 AUTUMN 2015 featuresWHEATON “ I consider my work a success if I can provide a showcase of God’s creation with my creation.” ➝ Facebook facebook.com/ 21 INNOVATORS: ART: wheatoncollege.il LEADING THE JIM HEIMBACH ’78 WAY / 21 / 32 Twitter twitter.com/ wheatoncollege COMMENCEMENT: STUDENT DEBT: GOD’S DOUBLE WHY IT’S WORTH IT Instagram AGENT 30 34 instagram.com/ / / wheatoncollegeil WHEATON.EDU/MAGAZINE THE WHEATON FUND + YOU IT ALL ADDS UP TO A BIG DIFFERENCE households gave to 6,650 the Wheaton Fund 75 households gave $10,000 or more to the Wheaton Fund 635 households made a first-time Wheaton Fund gift 5 households gave $100,000 or more to the Wheaton Fund $814,614.85 given by those who gave less than $1,000 to the Wheaton Fund 58.55% of dollars came from alumni 26.57% of dollars came from parents 14.88% of dollars came from friends Numbers included here represent giving through June 10, 2015 Thank you for all you did to make fiscal year 2015 successful! Make your Wheaton Fund gift today to help get fiscal year 2016 off to a strong start. -

Haitian Historical and Cultural Legacy

Haitian Historical and Cultural Legacy A Journey Through Time A Resource Guide for Teachers HABETAC The Haitian Bilingual/ESL Technical Assistance Center HABETAC The Haitian Bilingual/ESL Technical Assistance Center @ Brooklyn College 2900 Bedford Avenue James Hall, Room 3103J Brooklyn, NY 11210 Copyright © 2005 Teachers and educators, please feel free to make copies as needed to use with your students in class. Please contact HABETAC at 718-951-4668 to obtain copies of this publication. Funded by the New York State Education Department Acknowledgments Haitian Historical and Cultural Legacy: A Journey Through Time is for teachers of grades K through 12. The idea of this book was initiated by the Haitian Bilingual/ESL Technical Assistance Center (HABETAC) at City College under the direction of Myriam C. Augustin, the former director of HABETAC. This is the realization of the following team of committed, knowledgeable, and creative writers, researchers, activity developers, artists, and editors: Marie José Bernard, Resource Specialist, HABETAC at City College, New York, NY Menes Dejoie, School Psychologist, CSD 17, Brooklyn, NY Yves Raymond, Bilingual Coordinator, Erasmus Hall High School for Science and Math, Brooklyn, NY Marie Lily Cerat, Writing Specialist, P.S. 181, CSD 17, Brooklyn, NY Christine Etienne, Bilingual Staff Developer, CSD 17, Brooklyn, NY Amidor Almonord, Bilingual Teacher, P.S. 189, CSD 17, Brooklyn, NY Peter Kondrat, Educational Consultant and Freelance Writer, Brooklyn, NY Alix Ambroise, Jr., Social Studies Teacher, P.S. 138, CSD 17, Brooklyn, NY Professor Jean Y. Plaisir, Assistant Professor, Department of Childhood Education, City College of New York, New York, NY Claudette Laurent, Administrative Assistant, HABETAC at City College, New York, NY Christian Lemoine, Graphic Artist, HLH Panoramic, New York, NY. -

The Influence of Corporate Interests on USAID's Development Agenda

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 4-2-2012 The nflueI nce of Corporate Interests on USAID's Development Agenda: The aC se of Haiti Guy Metayer Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI12050218 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Metayer, Guy, "The nflueI nce of Corporate Interests on USAID's Development Agenda: The asC e of Haiti" (2012). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 609. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/609 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida THE INFLUENCE OF CORPORATE INTERESTS ON USAID'S DEVELOPMENT AGENDA: THE CASE OF HAITI A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in POLITICAL SCIENCE by Guy Metayer 2012 To: Dean Kenneth G. Furton choose the name of dean of your college/school College of Arts and Sciences choose the name of your college/school This dissertation, written by Guy Metayer, and entitled The Influence of Corporate Interests on USAID's Development Agenda: The Case of Haiti, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this dissertation and recommend that it be approved. _______________________________________ Richard S. Olson _______________________________________ John F. -

![CONCURRENT RESOLUTIONS—OCT. 6, 1988 102 STAT. 4909 ENROLLMENT CORRECTIONS—H.J. RES. 602 [S^N^R^Us] HAITI—DEMOCRATIC and EC](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3507/concurrent-resolutions-oct-6-1988-102-stat-4909-enrollment-corrections-h-j-res-602-s-n-r-us-haiti-democratic-and-ec-1993507.webp)

CONCURRENT RESOLUTIONS—OCT. 6, 1988 102 STAT. 4909 ENROLLMENT CORRECTIONS—H.J. RES. 602 [S^N^R^Us] HAITI—DEMOCRATIC and EC

CONCURRENT RESOLUTIONS—OCT. 6, 1988 102 STAT. 4909 ENROLLMENT CORRECTIONS—H.J. RES. 602 [s^n^R^us] Resolved by the Senate (the House of Representatives concurring), That, in the enrollment of the joint resolution (H.J. Res. 602) in support of the restoration of a free and independent Cambodia and the protection of the Cambodian people from a return to power by the genocidal Khmer Rouge, the Clerk of the House of Representa tives shall make the following corrections: (a) In subsection (2)— Ante, p. 2505. (1) strike out "in the context of a negotiated settlement"; and (2) strike out "in the context of a negotiated settlement,". (b) In subsection (10)— Ante, p. 2506. (1) strike out "immediately"; and (2) strike out "support and sanctuary" and insert: "assist- Biice". Agreed to October 4, 1988. HAITI—DEMOCRATIC AND ECONOMIC REFORMS [g.con.RrL] Whereas 29 years of repressive Duvalier rule came to end on February 7, 1986, when the Haitian people sent President-For-Life Jean-Claude Duvalier into exile; Whereas a National Governing Council, a military-dominated provi sional junta appointed by Duvalier prior to his departure and headed by General Henri Namphy, was named to govern the country and announced a plan to form a Constituent Assembly to draft a new constitution; Whereas on March 29, 1987, an overwhelming majority of Haitian voters (98.99 percent) approved the new constitution calling for the creation of a Provisional Electoral Council to draft an Electoral Law and oversee presidential and municipal elections; Whereas on November 29, -

Pygmalion Scheduled (Or March 12,13,14

Friday, March 6, 1964 ECHO TAYLOR UNIVERSITY — UPLAND, INDIANA VOL. XLIV —NO. 9 George B. Shaw's "Pygmalion Scheduled (or March 12,13,14 Pygmalion, a full length play by transformation, approved of the 12th 13th and 14th. George Bernard Shaw, will be pre project as a scientific experiment, The flower girl, Eliza Doolittle, sented at Taylor on March 12, 13, but did not agree with the inhu is portrayed by Marilyn Domhoff; and 14 at 8:15 in Shreiner Audi man treatment that Higgins gave Professor Higgins is played by torium. out to Eliza. Pickering is as intelli Bob Finch; and Colonel Pickering, Mr. Shaw wrote the play to im gent as Higgins, but he has man Higgin's Phonetician cohort, is press upon the public the impor ners becoming a gentleman, which portrayed by Tom Allen. are quite conspicious in Higgins tance of phoneticians in modern The other members of the cast by their absence. day society. include Cliff Robertson, Marion Pickering observes that Higgins Dodd, Eleanor Hustwick, Margo The plot involves Henry Hig- has brought Eliza up from one Dryer, Darlene Young, Ann Lentz, gins, an English speech teacher, grade of living in the direction of Dale Dickey, Gale Strain, and Bob who attempts to transform a Bob Finch, Eleanor Hustwick, and Tom Allen practice a scene another and in the process has Finton. cockney flower girl, Eliza Doo made her unfit for both lives. for the Trojan Player's production of Pygmalion. little, into an English lady by Tickets for the play may be Higgins thinks of himself as a teaching her to speak cultivated purchased prior to the date of very sufficient man until the hand English. -

Development Assistance in Haiti: Where Has the Money Gone?

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive DSpace Repository Theses and Dissertations 1. Thesis and Dissertation Collection, all items 2014-12 Development assistance in Haiti: where has the money gone? Anderson, Scott M. Monterey, California: Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/44512 Downloaded from NPS Archive: Calhoun NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS DEVELOPMENT ASSISTANCE IN HAITI: WHERE HAS THE MONEY GONE? by Scott M. Anderson December 2014 Thesis Advisor: Thomas C. Bruneau Second Reader: Robert E. Looney Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704–0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202–4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704–0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED December 2014 Master’s Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS DEVELOPMENT ASSISTANCE IN HAITI: WHERE HAS THE MONEY GONE? 6. AUTHOR(S) Scott M. Anderson 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION Naval Postgraduate School REPORT NUMBER Monterey, CA 93943–5000 9. SPONSORING /MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10.