University of Copenhagen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Africa 3Rd to 22Nd September 2015 (20 Days)

Hollyhead & Savage Trip Report South Africa 3rd to 22nd September 2015 (20 days) Female Cheetah with cubs and Impala kill by Heinz Ortmann Trip Report compiled by Tour Leader: Heinz Ortmann Trip Report Hollyhead & Savage Private South Africa September 2015 2 Tour Summary A fantastic twenty day journey that began in the beautiful Overberg region and fynbos of the Western Cape, included the Wakkerstroom grasslands, coastal dune forest of iSimangaliso Wetland Park, the Baobab-studded hills of Mapungubwe National Park and ended along a stretch of road searching for Kalahari specials north of Pretoria amongst many others. We experienced a wide variety of habitats and incredible birds and mammals. An impressive 400-plus birds and close to 50 mammal species were found on this trip. This, combined with visiting little-known parts of South Africa such as Magoebaskloof and Mapungubwe National Park, made this tour special as well as one with many unforgettable experiences and memories for the participants. Our journey started out from Cape Town International Airport at around lunchtime on a glorious sunny early-spring day. Our journey for the first day took us eastwards through the Overberg region and onto the Agulhas plains where we spent the next two nights. The farmlands in these parts appear largely barren and consist of single crop fields and yet host a surprising number of special, localised and endemic species. Our afternoon’s travels through these parts allowed us views of several more common and widespread species such as Egyptian and Spur-winged Geese, raptors like Jackal Buzzard, Rock Kestrel and Yellow-billed Kite, Speckled Pigeons, Capped Wheatear, Pied Starling, the ever present Pied and Cape Crow, White-necked Raven and Pin-tailed Whydah, almost in full breeding plumage. -

Uganda and Rwanda: Shoebill Experience, Nyungwe’S Albertine Rift and Great Apes

MEGAFARI: Uganda and Rwanda: Shoebill experience, Nyungwe’s Albertine Rift and Great Apes 16 – 27 April 2010 (12 days), Leader: Keith Barnes, Custom trip Photos by Keith Barnes. All photos taken on this trip. The spectacular Shoebill was the star of the show in Uganda, and a much-wanted species by all. Introduction This was the second leg of the Megafari – a true trip of a lifetime for most of the participants. Our Tanzania leg had already been the most successful trip we had ever had, netting an incredible 426 bird species in only 11 days. The main aims of the Uganda and Rwanda leg was to see a Shoebill stalking in deep Papyrus swamps, score a gamut of rainforest birds in both the lowlands of Budongo and then also the impressive montane forests of the incredible Nyungwe NP, and to see primates and of course, the irrepressible great apes, Chimpanzee and Mountain Gorilla. Fortunately, we achieved all these aims, netting 417 bird species on this 12-day leg of the trip, as well as accumulating an incredible 675 bird species and 62 mammals in just over three-weeks of the Megafari. The Megafari was a boon for spectacular birds and we saw 51 species of bird of prey, 11 species of turaco, 11 species of kingfisher, 10 species of bee-eater, 12 species of hornbill, and 25 species of sunbird. We also saw the famous Big-5 mammals and had incredible encounters with Mountain Gorillas and Chimpanzees amongst 11 species of primates. For the extremely successful Tanzania portion of the tour, click here. -

Government of the Republic of Sierra Leone Bumbuna Hydroelectric

Government of the Republic of Sierra Leone Ministry of Energy and Power Public Disclosure Authorized Bumbuna Hydroelectric Project Environmental Impact Assessment Draft Final Report - Appendices Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized January 2005 Public Disclosure Authorized in association with BMT Cordah Ltd Appendices Document Orientation The present EIA report is split into three separate but closely related documents as follows: Volume1 – Executive Summary Volume 2 – Main Report Volume 3 – Appendices This document is Volume 3 – Appendices. Nippon Koei UK, BMT Cordah and Environmental Foundation for Africa i Appendices Glossary of Acronyms AD Anno Domini AfDB African Development Bank AIDS Auto-Immune Deficiency Syndrome ANC Antenatal Care BCC Behavioural Change Communication BHP Bumbuna Hydroelectric Project BWMA Bumbuna Watershed Management Authority BOD Biochemical Oxygen Demand BP Bank Procedure (World Bank) CBD Convention on Biodiversity CHC Community Health Centre CHO Community Health Officer CHP Community Health Post CLC Community Liaison Committee COD Chemical Oxygen Demand dbh diameter at breast height DFID Department for International Development (UK) DHMT District Health Management Team DOC Dissolved Organic Carbon DRP Dam Review Panel DUC Dams Under Construction EA Environmental Assessment ECA Export Credit Agency EFA Environmental Foundation for Africa EHS Environment, Health and Safety EHSO Environment, Health and Safety Officer EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EMP Environmental Management Plan EPA -

Namibia Crane News 11

Namibia Crane News 11 July 2005 National B lue crane census proposed The Namibia Crane Working Group is investigating a national Blue Crane census, to obtain an update on numbers. This proposal corresponds with the recom- mended actions from the Red Data Book account for Blue Cranes (see Namibia Crane News No. 6). The last count in December 1994 provided a total estimate of 49 adults and 11 yearlings. It will be interesting to see whether the population is still declining after the recent good rains. Ideally the census would include an aerial survey of Etosha and the grassland areas to the north, together with ground surveys. We are still deciding on the best time of year for the census, bearing in mind that we would like to pick up as many juveniles as Enthusiastic Kasika and Impalila guides out birding possible. Any incidental observations of the other two (Photo: Sandra Slater-Jones) crane species would also be noted, but a full census of help bird enthusiasts find Rosy-throated Longclaw, the latter species would probably be more feasible after Black Coucal, Luapula Cisticola, Slaty egret, African the rainy season, when the non-resident Wattled Skimmer, Swamp Boubou, Western Banded Snake Cranes visit the Nyae Nyae pans. You are welcome to Eagle and other exciting species like African Finfoot contact us with any comments and suggestions! Lesser Jacana, Pygmy Geese and Pel's Fishing Owl. Caprivi bird conservation/tourism grows! The Open Africa Initiative has expressed interest in Sandra Slater-Jones (Conservation International incorporating Kasika and Impalila Conservancy - Chobe Project: Field Facilitator) tourism activities into the "Open Africa Zambia Tel: +264 66 254 254; Cell: +264 81 2896889 Route" currently being investigated. -

Laniarius Spp.) in Coastal Kenya and Somalia

Brian W. Finch et al. 74 Bull. B.O.C. 2016 136(2) Redefining the taxonomy of the all-black and pied boubous (Laniarius spp.) in coastal Kenya and Somalia by Brian W. Finch, Nigel D. Hunter, Inger Winkelmann, Karla Manzano-Vargas, Peter Njoroge, Jon Fjeldså & M. Thomas P. Gilbert Received 21 October 2015 Summary.—Following the rediscovery of a form of Laniarius on Manda Island, Kenya, which had been treated as a melanistic morph of Tropical Boubou Laniarius aethiopicus for some 70 years, a detailed field study strongly indicated that it was wrongly assigned. Molecular examination proved that it is the same species as L. (aethiopicus) erlangeri, until now considered a Somali endemic, and these populations should take the oldest available name L. nigerrimus. The overall classification of coastal boubous also proved to require revision, and this paper presents a preliminary new classification for taxa in this region using both genetic and morphological data. Genetic evidence revealed that the coastal ally of L. aethiopicus, recently considered specifically as L. sublacteus, comprises two unrelated forms, requiring a future detailed study. The black-and-white boubous—characteristic birds of Africa’s savanna and wooded regions—have been treated as subspecies of the highly polytypic Laniarius ferrugineus (Rand 1960), or subdivided, by separating Southern Boubou L. ferrugineus, Swamp Boubou L. bicolor and Turati’s Boubou L. turatii from the widespread and geographically variable Tropical Boubou L. aethiopicus (Hall & Moreau 1970, Fry et al. 2000, Harris & Franklin 2000). They are generally pied, with black upperparts, white or pale buff underparts, and in most populations a white wing-stripe. -

Birders Checklist for the Mapungubwe National Park and Area

Birders Checklist for the Mapungubwe National Park and area Reproduced with kind permission of Etienne Marais of Indicator Birding Visit www.birding.co.za for more info and details of birding tours and events Endemic birds KEY: SA = South African Endemic, SnA = Endemic to Southern Africa, NE = Near endemic (Birders endemic) to the Southern African Region. RAR = Rarity Status KEY: cr = common resident; nr = nomadic breeding resident; unc = uncommon resident; rr = rare; ? = status uncertain; s = summer visitor; w = winter visitor r Endemicity Numbe Sasol English Status All Scientific p 30 Little Grebe cr Tachybaptus ruficollis p 30 Black-necked Grebe nr Podiceps nigricollis p 56 African Darter cr Anhinga rufa p 56 Reed Cormorant cr Phalacrocorax africanus p 56 White-breasted Cormorant cr Phalacrocorax lucidus p 58 Great White Pelican nr Pelecanus onocrotalus p 58 Pink-backed Pelican ? Pelecanus rufescens p 60 Grey Heron cr Ardea cinerea p 60 Black-headed Heron cr Ardea melanocephala p 60 Goliath Heron cr Ardea goliath p 60 Purple Heron uncr Ardea purpurea p 62 Little Egret uncr Egretta garzetta p 62 Yellow-billed Egret uncr Egretta intermedia p 62 Great Egret cr Egretta alba p 62 Cattle Egret cr Bubulcus ibis p 62 Squacco Heron cr Ardeola ralloides p 64 Black Heron uncs Egretta ardesiaca p 64 Rufous-bellied Heron ? Ardeola rufiventris RA p 64 White-backed Night-Heron rr Gorsachius leuconotus RA p 64 Slaty Egret ? Egretta vinaceigula p 66 Green-backed Heron cr Butorides striata p 66 Black-crowned Night-Heron uncr Nycticorax nycticorax p -

South Africa Mega Birding Tour I 6Th to 30Th January 2018 (25 Days) Trip Report

South Africa Mega Birding Tour I 6th to 30th January 2018 (25 days) Trip Report Aardvark by Mike Bacon Trip report compiled by Tour Leader: Wayne Jones Rockjumper Birding Tours View more tours to South Africa Trip Report – RBT South Africa - Mega I 2018 2 Tour Summary The beauty of South Africa lies in its richness of habitats, from the coastal forests in the east, through subalpine mountain ranges and the arid Karoo to fynbos in the south. We explored all of these and more during our 25-day adventure across the country. Highlights were many and included Orange River Francolin, thousands of Cape Gannets, multiple Secretarybirds, stunning Knysna Turaco, Ground Woodpecker, Botha’s Lark, Bush Blackcap, Cape Parrot, Aardvark, Aardwolf, Caracal, Oribi and Giant Bullfrog, along with spectacular scenery, great food and excellent accommodation throughout. ___________________________________________________________________________________ Despite havoc-wreaking weather that delayed flights on the other side of the world, everyone managed to arrive (just!) in South Africa for the start of our keenly-awaited tour. We began our 25-day cross-country exploration with a drive along Zaagkuildrift Road. This unassuming stretch of dirt road is well-known in local birding circles and can offer up a wide range of species thanks to its variety of habitats – which include open grassland, acacia woodland, wetlands and a seasonal floodplain. After locating a handsome male Northern Black Korhaan and African Wattled Lapwings, a Northern Black Korhaan by Glen Valentine -

Zambia and Zimbabwe 28 �Ovember – 6 December 2009

Zambia and Zimbabwe 28 ovember – 6 December 2009 Guide: Josh Engel A Tropical Birding Custom Tour All photos taken by the guide on this tour. The Smoke that Thunders: looking down one end of the mile-long Victoria Falls. ITRODUCTIO We began this tour by seeing one of Africa’s most beautiful and sought after birds: African Pitta . After that, the rest was just details. But not really, considering we tacked on 260 more birds and loads of great mammals. We saw Zambia’s only endemic bird, Chaplin’s Barbet , as well as a number of miombo and broad-leaf specialties, including Miombo Rock-Thrush, Racket-tailed Roller, Southern Hyliota, Miombo Pied Barbet, Miombo Glossy Starling, Bradfield’s Hornbill, Pennant-winged ightjar, and Three-banded Courser. With the onset of the rainy season just before the tour, the entire area was beautifully green and was inundated with migrants, so we were able to rack up a great list of cuckoos and other migrants, including incredible looks at a male Kurrichane Buttonquail . Yet the Zambezi had not begun to rise, so Rock Pratincole still populated the river’s rocks, African Skimmer its sandbars, and Lesser Jacana and Allen’s Gallinule its grassy margins. Mammals are always a highlight of any Africa tour: this trip’s undoubted star was a leopard , while a very cooperative serval was also superb. Victoria Falls was incredible, as usual. We had no problems in Zimbabwe whatsoever, and our lodge there on the shores of the Zambezi River was absolutely stunning. The weather was perfect throughout the tour, with clouds often keeping the temperature down and occasional rains keeping bird activity high. -

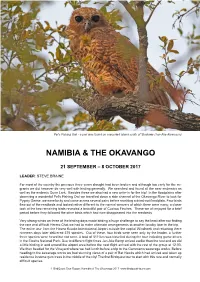

Namibia & the Okavango

Pel’s Fishing Owl - a pair was found on a wooded island south of Shakawe (Jan-Ake Alvarsson) NAMIBIA & THE OKAVANGO 21 SEPTEMBER – 8 OCTOBER 2017 LEADER: STEVE BRAINE For most of the country the previous three years drought had been broken and although too early for the mi- grants we did however do very well with birding generally. We searched and found all the near endemics as well as the endemic Dune Lark. Besides these we also had a new write-in for the trip! In the floodplains after observing a wonderful Pel’s Fishing Owl we travelled down a side channel of the Okavango River to look for Pygmy Geese, we were lucky and came across several pairs before reaching a dried-out floodplain. Four birds flew out of the reedbeds and looked rather different to the normal weavers of which there were many, a closer look at the two remaining birds revealed a beautiful pair of Cuckoo Finches. These we all enjoyed for a brief period before they followed the other birds which had now disappeared into the reedbeds. Very strong winds on three of the birding days made birding a huge challenge to say the least after not finding the rare and difficult Herero Chat we had to make alternate arrangements at another locality later in the trip. The entire tour from the Hosea Kutako International Airport outside the capital Windhoek and returning there nineteen days later delivered 375 species. Out of these, four birds were seen only by the leader, a further three species were heard but not seen. -

Bird Diversity and Land Use on the Slopes of Mt

Bird diversity and land use on the slopes of Mt. Kilimanjaro and the adjacent plains, Tanzania Bird diversity and land use on the slopes of Mt. Kilimanjaro and the adjacent plains, Tanzania Eija Soini Correct citation: Soini E. 2006. Bird diversity and land use on the slopes of Mt. Kilimanjaro and the adjacent plains, Tanzania. ICRAF Working Paper no. 11. Nairobi, Kenya: World Agroforestry Centre. Titles in the Working Paper Series aim to disseminate interim results on agroforestry research and practices and stimulate feedback from the scientific community. Other publication series from the World Agroforestry Centre include: Agroforestry Perspectives, Technical Manuals and Occasional Papers. Published by the World Agroforestry Centre United Nations Avenue PO Box 30677, GPO 00100 Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254(0)20 7224000, via USA +1 650 833 6645 Fax: +254(0)20 7224001, via USA +1 650 833 6646 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.worldagroforestry.org © World Agroforestry Centre 2006 ICRAF Working Paper no. 11 The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the World Agroforestry Centre. Articles appearing in this publication may be quoted or reproduced without charge, provided the source is acknowledged. No use of this publication may be made for resale or other commercial purposes. All images remain the sole property of their source and may not be used for any purpose without written permission of the source. 2 About the author Eija Soini has a Masters degree in Development Geography from the University of Helsinki, Finland. She has also studied a range of other subjects including Biology, African studies, Cultural Anthropology, Education, and Remote Sensing and GIS. -

Preliminary Systematic Notes on Some Old World Passerines

Kiv. ital. Orn., Milano, 59 (3-4): 183-195, 15-XII-1989 STOBRS L. OLSON PRELIMINARY SYSTEMATIC NOTES ON SOME OLD WORLD PASSERINES TIPOGKAFIA FUSI - PAVIA 1989 Riv. ital. Ora., Milano, 59 (3-4): 183-195, 15-XII-1989 STORRS L. OLSON (*) PRELIMINARY SYSTEMATIC NOTES ON SOME OLD WORLD PASSERINES Abstract. — The relationships of various genera of Old World passerines are assessed based on osteological characters of the nostril and on morphology of the syrinx. Chloropsis belongs in the Pycnonotidae. Nicator is not a bulbul and is returned to the Malaconotidae. Neolestes is probably not a bulbul. The Malagasy species placed in the genus Phyllastrephus are not bulbuls and are returned to the Timaliidae. It is confirmed that the relationships of Paramythia, Oreocharis, Malia, Tylas, Hyper - gerus, Apalopteron, and Lioptilornis (Kupeornis) are not with the Pycnonotidae. Trochocercus nitens and T. cycmomelas are monarchine flycatchers referable to the genus TerpsiphoTie. « Trochocercus s> nigromitratus, « T. s> albiventer, and « T. » albo- notatus are tentatively referred to Elminia. Neither Elminia nor Erythrocercus are monarch] nes and must be removed from the Myiagridae (Monarchidae auct.). Grai- lina and Aegithina- are monarch flycatchers referable to the Myiagridae. Eurocephalus belongs in the Laniinae, not the Prionopinae. Myioparus plumbeus is confirmed as belonging in the Muscicapidae. Pinarornis lacks the turdine condition of the syrinx. It appears to be most closely related to Neoeossypha, Stizorhina, and Modulatrix, and these four genera are placed along with Myadestes in a subfamily Myadestinae that is the primitive sister-group of the remainder of the Muscicapidae, all of which have a derived morphology of the syrinx. -

An Update of Wallacels Zoogeographic Regions of the World

REPORTS To examine the temporal profile of ChC produc- specification of a distinct, and probably the last, 3. G. A. Ascoli et al., Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 557 (2008). tion and their correlation to laminar deployment, cohort in this lineage—the ChCs. 4. J. Szentágothai, M. A. Arbib, Neurosci. Res. Program Bull. 12, 305 (1974). we injected a single pulse of BrdU into pregnant A recent study demonstrated that progeni- CreER 5. P. Somogyi, Brain Res. 136, 345 (1977). Nkx2.1 ;Ai9 females at successive days be- tors below the ventral wall of the lateral ventricle 6. L. Sussel, O. Marin, S. Kimura, J. L. Rubenstein, tween E15 and P1 to label mitotic progenitors, (i.e., VGZ) of human infants give rise to a medial Development 126, 3359 (1999). each paired with a pulse of tamoxifen at E17 to migratory stream destined to the ventral mPFC 7. S. J. Butt et al., Neuron 59, 722 (2008). + 18 8. H. Taniguchi et al., Neuron 71, 995 (2011). label NKX2.1 cells (Fig. 3A). We first quanti- ( ). Despite species differences in the develop- 9. L. Madisen et al., Nat. Neurosci. 13, 133 (2010). fied the fraction of L2 ChCs (identified by mor- mental timing of corticogenesis, this study and 10. J. Szabadics et al., Science 311, 233 (2006). + phology) in mPFC that were also BrdU+. Although our findings raise the possibility that the NKX2.1 11. A. Woodruff, Q. Xu, S. A. Anderson, R. Yuste, Front. there was ChC production by E15, consistent progenitors in VGZ and their extended neurogenesis Neural Circuits 3, 15 (2009).