An Ecological Survey of Northeastern Botswana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Africa: Magoebaskloof and Kruger National Park Custom Tour Trip Report

SOUTH AFRICA: MAGOEBASKLOOF AND KRUGER NATIONAL PARK CUSTOM TOUR TRIP REPORT 24 February – 2 March 2019 By Jason Boyce This Verreaux’s Eagle-Owl showed nicely one late afternoon, puffing up his throat and neck when calling www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | TRIP REPORT South Africa: Magoebaskloof and Kruger National Park February 2019 Overview It’s common knowledge that South Africa has very much to offer as a birding destination, and the memory of this trip echoes those sentiments. With an itinerary set in one of South Africa’s premier birding provinces, the Limpopo Province, we were getting ready for a birding extravaganza. The forests of Magoebaskloof would be our first stop, spending a day and a half in the area and targeting forest special after forest special as well as tricky range-restricted species such as Short-clawed Lark and Gurney’s Sugarbird. Afterwards we would descend the eastern escarpment and head into Kruger National Park, where we would make our way to the northern sections. These included Punda Maria, Pafuri, and the Makuleke Concession – a mouthwatering birding itinerary that was sure to deliver. A pair of Woodland Kingfishers in the fever tree forest along the Limpopo River Detailed Report Day 1, 24th February 2019 – Transfer to Magoebaskloof We set out from Johannesburg after breakfast on a clear Sunday morning. The drive to Polokwane took us just over three hours. A number of birds along the way started our trip list; these included Hadada Ibis, Yellow-billed Kite, Southern Black Flycatcher, Village Weaver, and a few brilliant European Bee-eaters. -

Namibia Crane News 11

Namibia Crane News 11 July 2005 National B lue crane census proposed The Namibia Crane Working Group is investigating a national Blue Crane census, to obtain an update on numbers. This proposal corresponds with the recom- mended actions from the Red Data Book account for Blue Cranes (see Namibia Crane News No. 6). The last count in December 1994 provided a total estimate of 49 adults and 11 yearlings. It will be interesting to see whether the population is still declining after the recent good rains. Ideally the census would include an aerial survey of Etosha and the grassland areas to the north, together with ground surveys. We are still deciding on the best time of year for the census, bearing in mind that we would like to pick up as many juveniles as Enthusiastic Kasika and Impalila guides out birding possible. Any incidental observations of the other two (Photo: Sandra Slater-Jones) crane species would also be noted, but a full census of help bird enthusiasts find Rosy-throated Longclaw, the latter species would probably be more feasible after Black Coucal, Luapula Cisticola, Slaty egret, African the rainy season, when the non-resident Wattled Skimmer, Swamp Boubou, Western Banded Snake Cranes visit the Nyae Nyae pans. You are welcome to Eagle and other exciting species like African Finfoot contact us with any comments and suggestions! Lesser Jacana, Pygmy Geese and Pel's Fishing Owl. Caprivi bird conservation/tourism grows! The Open Africa Initiative has expressed interest in Sandra Slater-Jones (Conservation International incorporating Kasika and Impalila Conservancy - Chobe Project: Field Facilitator) tourism activities into the "Open Africa Zambia Tel: +264 66 254 254; Cell: +264 81 2896889 Route" currently being investigated. -

Laniarius Spp.) in Coastal Kenya and Somalia

Brian W. Finch et al. 74 Bull. B.O.C. 2016 136(2) Redefining the taxonomy of the all-black and pied boubous (Laniarius spp.) in coastal Kenya and Somalia by Brian W. Finch, Nigel D. Hunter, Inger Winkelmann, Karla Manzano-Vargas, Peter Njoroge, Jon Fjeldså & M. Thomas P. Gilbert Received 21 October 2015 Summary.—Following the rediscovery of a form of Laniarius on Manda Island, Kenya, which had been treated as a melanistic morph of Tropical Boubou Laniarius aethiopicus for some 70 years, a detailed field study strongly indicated that it was wrongly assigned. Molecular examination proved that it is the same species as L. (aethiopicus) erlangeri, until now considered a Somali endemic, and these populations should take the oldest available name L. nigerrimus. The overall classification of coastal boubous also proved to require revision, and this paper presents a preliminary new classification for taxa in this region using both genetic and morphological data. Genetic evidence revealed that the coastal ally of L. aethiopicus, recently considered specifically as L. sublacteus, comprises two unrelated forms, requiring a future detailed study. The black-and-white boubous—characteristic birds of Africa’s savanna and wooded regions—have been treated as subspecies of the highly polytypic Laniarius ferrugineus (Rand 1960), or subdivided, by separating Southern Boubou L. ferrugineus, Swamp Boubou L. bicolor and Turati’s Boubou L. turatii from the widespread and geographically variable Tropical Boubou L. aethiopicus (Hall & Moreau 1970, Fry et al. 2000, Harris & Franklin 2000). They are generally pied, with black upperparts, white or pale buff underparts, and in most populations a white wing-stripe. -

Namibia & the Okavango

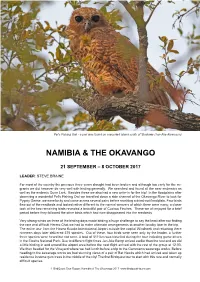

Pel’s Fishing Owl - a pair was found on a wooded island south of Shakawe (Jan-Ake Alvarsson) NAMIBIA & THE OKAVANGO 21 SEPTEMBER – 8 OCTOBER 2017 LEADER: STEVE BRAINE For most of the country the previous three years drought had been broken and although too early for the mi- grants we did however do very well with birding generally. We searched and found all the near endemics as well as the endemic Dune Lark. Besides these we also had a new write-in for the trip! In the floodplains after observing a wonderful Pel’s Fishing Owl we travelled down a side channel of the Okavango River to look for Pygmy Geese, we were lucky and came across several pairs before reaching a dried-out floodplain. Four birds flew out of the reedbeds and looked rather different to the normal weavers of which there were many, a closer look at the two remaining birds revealed a beautiful pair of Cuckoo Finches. These we all enjoyed for a brief period before they followed the other birds which had now disappeared into the reedbeds. Very strong winds on three of the birding days made birding a huge challenge to say the least after not finding the rare and difficult Herero Chat we had to make alternate arrangements at another locality later in the trip. The entire tour from the Hosea Kutako International Airport outside the capital Windhoek and returning there nineteen days later delivered 375 species. Out of these, four birds were seen only by the leader, a further three species were heard but not seen. -

University of Copenhagen

Redefining the taxonomy of the all-black and pied boubous (Laniarius spp.) in coastal Kenya and Somalia Finch, Brian W.; Hunter, Nigel D.; Winkelmann, Inger Eleanor Hall; Manzano Vargas, Karla; Njoroge, Peter; Fjeldså, Jon; Gilbert, Tom Published in: Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club Publication date: 2016 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (APA): Finch, B. W., Hunter, N. D., Winkelmann, I. E. H., Manzano Vargas, K., Njoroge, P., Fjeldså, J., & Gilbert, T. (2016). Redefining the taxonomy of the all-black and pied boubous (Laniarius spp.) in coastal Kenya and Somalia. Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club, 136(2), 74-85. http://boc- online.org/bulletins/downloads/BBOC1362-Finch.pdf Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 Brian W. Finch et al. 74 Bull. B.O.C. 2016 136(2) Redefining the taxonomy of the all-black and pied boubous (Laniarius spp.) in coastal Kenya and Somalia by Brian W. Finch, Nigel D. Hunter, Inger Winkelmann, Karla Manzano-Vargas, Peter Njoroge, Jon Fjeldså & M. Thomas P. Gilbert Received 21 October 2015 Summary.—Following the rediscovery of a form of Laniarius on Manda Island, Kenya, which had been treated as a melanistic morph of Tropical Boubou Laniarius aethiopicus for some 70 years, a detailed field study strongly indicated that it was wrongly assigned. Molecular examination proved that it is the same species as L. (aethiopicus) erlangeri, until now considered a Somali endemic, and these populations should take the oldest available name L. nigerrimus. The overall classification of coastal boubous also proved to require revision, and this paper presents a preliminary new classification for taxa in this region using both genetic and morphological data. -

South Africa Mega Birding III 5Th to 27Th October 2019 (23 Days) Trip Report

South Africa Mega Birding III 5th to 27th October 2019 (23 days) Trip Report The near-endemic Gorgeous Bushshrike by Daniel Keith Danckwerts Tour leader: Daniel Keith Danckwerts Trip Report – RBT South Africa – Mega Birding III 2019 2 Tour Summary South Africa supports the highest number of endemic species of any African country and is therefore of obvious appeal to birders. This South Africa mega tour covered virtually the entire country in little over a month – amounting to an estimated 10 000km – and targeted every single endemic and near-endemic species! We were successful in finding virtually all of the targets and some of our highlights included a pair of mythical Hottentot Buttonquails, the critically endangered Rudd’s Lark, both Cape, and Drakensburg Rockjumpers, Orange-breasted Sunbird, Pink-throated Twinspot, Southern Tchagra, the scarce Knysna Woodpecker, both Northern and Southern Black Korhaans, and Bush Blackcap. We additionally enjoyed better-than-ever sightings of the tricky Barratt’s Warbler, aptly named Gorgeous Bushshrike, Crested Guineafowl, and Eastern Nicator to just name a few. Any trip to South Africa would be incomplete without mammals and our tally of 60 species included such difficult animals as the Aardvark, Aardwolf, Southern African Hedgehog, Bat-eared Fox, Smith’s Red Rock Hare and both Sable and Roan Antelopes. This really was a trip like no other! ____________________________________________________________________________________ Tour in Detail Our first full day of the tour began with a short walk through the gardens of our quaint guesthouse in Johannesburg. Here we enjoyed sightings of the delightful Red-headed Finch, small numbers of Southern Red Bishops including several males that were busy moulting into their summer breeding plumage, the near-endemic Karoo Thrush, Cape White-eye, Grey-headed Gull, Hadada Ibis, Southern Masked Weaver, Speckled Mousebird, African Palm Swift and the Laughing, Ring-necked and Red-eyed Doves. -

Title of Thesis Or Dissertation, Worded

HUMAN-WILDLIFE CONFLICT AND ECOTOURISM: COMPARING PONGARA AND IVINDO NATIONAL PARKS IN GABON by SANDY STEVEN AVOMO NDONG A THESIS Presented to the Department of International Studies and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts September 2017 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Sandy Steven Avomo Ndong Title: Human-wildlife Conflict: Comparing Pongara and Ivindo National Parks in Gabon This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of International Studies by: Galen Martin Chairperson Angela Montague Member Derrick Hindery Member and Sara D. Hodges Interim Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded September 2017 ii © 2017 Sandy Steven Avomo Ndong iii THESIS ABSTRACT Sandy Steven Avomo Ndong Master of Arts Department of International Studies September 2017 Title: Human-wildlife Conflict: Comparing Pongara and Ivindo National Parks in Gabon Human-wildlife conflicts around protected areas are important issues affecting conservation, especially in Africa. In Gabon, this conflict revolves around crop-raiding by protected wildlife, especially elephants. Elephants’ crop-raiding threaten livelihoods and undermines conservation efforts. Gabon is currently using monetary compensation and electric fences to address this human-elephant conflict. This thesis compares the impacts of the human-elephant conflict in Pongara and Ivindo National Parks based on their idiosyncrasy. Information was gathered through systematic review of available literature and publications, observation, and semi-structured face to face interviews with local residents, park employees, and experts from the National Park Agency. -

ZIMBABWE CHECKLIST R=Rare, V=Vagrant, ?=Confirmation Required

ZIMBABWE CHECKLIST R=rare, V=vagrant, ?=confirmation required Common Ostrich Red-billed Teal Dark Chanting-goshawk Great Crested Grebe V Northern Pintail R Western Marsh-harrier Black-necked Grebe R Garganey African Marsh-harrier Little Grebe Northern Shoveler V Montagu's Harrier European Storm-petrel V Cape Shoveler Pallid Harrier Great White Pelican Southern Pochard African Harrier-hawk Pink-backed Pelican African Pygmy-goose Osprey White-breasted Cormorant Comb Duck Peregrine Falcon Reed Cormorant Spur-winged Goose Lanner Falcon African Darter Maccoa Duck Eurasian Hobby Greater Frigatebird V Secretarybird African Hobby Grey Heron Egyptian Vulture V Sooty Falcon R Black-headed Heron Hooded Vulture Taita Falcon Goliath Heron Cape Vulture Red-necked Falcon Purple Heron White-backed Vulture Red-footed Falcon Great Egret Rüppell's Vulture V Amur Falcon Little Egret Lappet-faced Vulture Rock Kestrel Yellow-billed Egret White-headed Vulture Greater Kestrel Black Heron Black Kite Lesser Kestrel Slaty Egret R Black-shouldered Kite Dickinson's Kestrel Cattle Egret African Cuckoo Hawk Coqui Francolin Squacco Heron Bat Hawk Crested Francolin Malagasy Pond-heron R European Honey-buzzard Shelley's Francolin Green-backed Heron Verreaux's Eagle Red-billed Spurfowl Rufous-bellied Heron Tawny Eagle Natal Spurfowl Black-crowned Night-heron Steppe Eagle Red-necked Spurfowl White-backed Night-heron Lesser Spotted Eagle Swainson's Spurfowl Little Bittern Wahlberg's Eagle Common Quail Dwarf Bittern Booted Eagle Harlequin Quail Eurasian Bittern V African -

Swamp Boubou

420 Malaconotidae: boubous, tchagras and bush shrikes Swamp Boubou 14˚ Moeraswaterfiskaal SWAMP BOUBOU Laniarius bicolor 1 5 The Swamp Boubou ranges widely over western 18˚ tropical Africa (Harris & Arnott 1988; Maclean 1993b), but it occurs only marginally in southern Africa where it is restricted to the large floodplains and rivers in northern Botswana and Namibia 22˚ (Caprivi Strip, Okavango Delta, Kavango– 6 Kwando–Linyanti–Chobe rivers, Kunene River). 2 It occurs in the extreme west of Zimbabwe, up- stream from Victoria Falls (1725DD) (Pollard 26˚ 1992b; Chittenden & Pollard 1994). It is a strikingly pied but rather skulking bird and, except for its loud duetting vocalizations, it can easily be overlooked. The typical habitat is 3 7 riparian woodland and thickets fringing rivers and 30˚ floodplains, preferably adjacent to mature swamp with tall reeds, dense papyrus and Water Figs Ficus verucculosa. In fringing gallery woodland in 4 8 the Okavango Swamps and along the Linyanti 34˚ River, average densities of 1–2 birds/10 ha have 18˚ 22˚ 26˚ been recorded (unpubl. data). 10˚ 14˚ 30˚ 34˚ No movements have been documented in the region, and the pattern in the model for Zone 1 could be related to seasonal differences in calling frequency. Breeding has been documented throughout the year in Botswana, possibly with a peak in early spring (Skinner 1995a). The Recorded in 126 grid cells, 2.8% scattered breeding might be related to peak floods gradually Total number of records: 807 progressing down through the Okavango over a period of Mean reporting rate for range: 41.3% several months in the dry season. -

Ultimate Zambia (Including Pitta) Tour

BIRDING AFRICA THE AFRICA SPECIALISTS Ultimate Zambia including Zambia Pitta 2019 Tour Report © Yann Muzika © Yann African Pitta Text by tour leader Michael Mills Photos by tour participants Yann Muzika, John Clark and Roger Holmberg SUMMARY Our first Ultimate Zambia Tour was a resounding success. It was divided into three more manageable sections, namely the North-East Extension, © John Clark © John Main Zambia Tour and Zambia Pitta Tour, each with its own delights. Birding Africa Tour Report Tour Africa Birding On the North-East Pre-Tour we started off driving We commenced the Main Zambia Tour at the Report Tour Africa Birding north from Lusaka to the Bangweulu area, where spectacular Mutinondo Wilderness. It was apparent we found good numbers of Katanga Masked that the woodland and mushitu/gallery forest birds Weaver coming into breeding plumage. Further were finishing breeding, making it hard work to Rosy-throated Longclaw north at Lake Mweru we enjoyed excellent views of track down all the key targets, but we enjoyed good Zambian Yellow Warbler (split from Papyrus Yellow views of Bar-winged Weaver and Laura's Woodland Warbler) and more Katanga Masked Weavers not Warbler and found a pair of Bohm's Flycatchers finally connected with a pair of Whyte's Francolin, Miombo Tit, Bennett's Woodpecker, Amur Falcon, yet in breeding plumage. From here we headed east feeding young. Other highlights included African which we managed to flush. From Mutinondo Cuckoo Finch, African Scops Owl, White-crested to the Mbala area we then visited the Saisi River Barred Owlet, Miombo Rock Thrush and Spotted we headed west with our ultimate destination as Helmetshrike and African Spotted Creeper. -

Bird Surveys in the Gamba Complex of Protected Areas, Gabon

Bird Surveys in the Gamba Complex of Protected Areas, Gabon George ANGEHR1, Brian SCHMIDT2, Francis NJIE3, Patrice CHRISTY4, Christina GEBHARD2, Landry TCHIGNOUMBA5 and Martin A.E. OMBENOTORI6 1 Introduction status of protected areas within the complex was revised, and two areas, Loango and Moukalaba- Approximately 2,100 species of birds are known from Doudou, were upgraded to National Parks. An analy- Africa south of the Sahara. Gabon is fairly well known sis by BirdLife International (Christy 2001) found the ornithologically, the first collections having been made Gamba Complex to qualify as one of Gabon’s six by du Chaillu as early as the 1850s. To date, 678 Important Bird Areas (IBAs). Important Bird Areas species have been recorded in the country (Christy are areas that have been determined to be most impor- 2001), or about 30% of the total known for sub- tant for the conservation of birds at the global level, Saharan Africa. Gabon’s bird diversity is relatively lim- based on the distribution of endangered, endemic, ited compared to some other Afrotropical countries, habitat-restricted, and congregatory species. such as Cameroon, which has more than 900 species. Despite its importance, there has been relatively lit- The main factors involved include its relatively small tle published ornithological work on the Gamba size and lack of habitat and topographic diversity. The Complex. Sargeant (1993) was resident at Gamba for natural vegetation of most of Gabon is lowland ever- five years and compiled a bird list for the immediate green and semi-evergreen forest, with only limited area, and as well as lists for other localities within the areas of savanna in the east and south, and its maxi- Complex, including Rabi, the Rembo (River) Ndogo, mum elevation is 1,575 m, compared to 4,095 m for and the east side of the Moukalaba Faunal Reserve, Cameroon. -

Namibia & Botswana

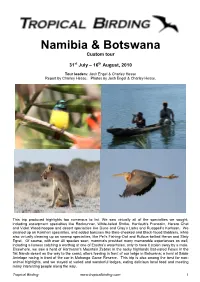

Namibia & Botswana Custom tour 31st July – 16th August, 2010 Tour leaders: Josh Engel & Charley Hesse Report by Charley Hesse. Photos by Josh Engel & Charley Hesse. This trip produced highlights too numerous to list. We saw virtually all of the specialties we sought, including escarpment specialties like Rockrunner, White-tailed Shrike, Hartlaub‟s Francolin, Herero Chat and Violet Wood-hoopoe and desert specialties like Dune and Gray‟s Larks and Rueppell‟s Korhaan. We cleaned up on Kalahari specialties, and added bonuses like Bare-cheeked and Black-faced Babblers, while also virtually cleaning up on swamp specialties, like Pel‟s Fishing-Owl and Rufous-bellied Heron and Slaty Egret. Of course, with over 40 species seen, mammals provided many memorable experiences as well, including a lioness catching a warthog at one of Etosha‟s waterholes, only to have it stolen away by a male. Elsewhere, we saw a herd of Hartmann‟s Mountain Zebras in the rocky highlands Bat-eared Foxes in the flat Namib desert on the way to the coast; otters feeding in front of our lodge in Botswana; a herd of Sable Antelope racing in front of the car in Mahango Game Reserve. This trip is also among the best for non- animal highlights, and we stayed at varied and wonderful lodges, eating delicious local food and meeting many interesting people along the way. Tropical Birding www.tropicalbirding.com 1 The rarely seen arboreal Acacia Rat (Thallomys) gnaws on the bark of Acacia trees (Charley Hesse). 31st July After meeting our group at the airport, we drove into Nambia‟s capital, Windhoek, seeing several interesting birds and mammals along the way.