May Tcu 0229M 10286.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Postsecondary Forestry Technology

2007 Mississippi Curriculum Framework Postsecondary Forestry Technology (Program CIP: 03.0511 – Forest Technology/Technician) Direct inquiries to Debra West Director for Career and Technical Education State Board for Community and Junior Colleges 3825 Ridgewood Road Jackson, MS 39211 (601) 432-6518 [email protected] Jimmy McCully, Ph.D. Coordinator, Agricultural Education and Special Initiatives Research and Curriculum Unit P.O. Drawer DX Mississippi State, MS 39762 (662) 325-2510 [email protected] Additional copies Research and Curriculum Unit for Workforce Development Vocational and Technical Education Attention: Reference Room and Media Center Coordinator P.O. Drawer DX Mississippi State, MS 39762 http://cia.rcu.msstate.edu/curriculum/download.asp (662) 325-2510 Published by Office of Vocational Education and Workforce Development Mississippi Department of Education Jackson, MS 39205 Research and Curriculum Unit for Workforce Development Vocational and Technical Education Mississippi State University Mississippi State, MS 39762 The Mississippi Department of Education, Office of Vocational Education and Workforce Development does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin, sex, age, or disability in the provision of educational programs and services or employment opportunities and benefits. The following office has been designated to handle inquiries and complaints regarding the non-discrimination policies of the Mississippi Department of Education: Director, Office of Human Resources, Mississippi Department -

EC82-1738 Tree Planting Guide

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Historical Materials from University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension Extension 1982 EC82-1738 Tree Planting Guide William R. Lovett University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Bruce E. Bolander University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/extensionhist Part of the Agriculture Commons, and the Curriculum and Instruction Commons Lovett, William R. and Bolander, Bruce E., "EC82-1738 Tree Planting Guide" (1982). Historical Materials from University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension. 836. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/extensionhist/836 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Extension at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Historical Materials from University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Nebraska Cooperative Extension EC82-1738 Tree Planting Guide by Bill Lovett, Tree Improvement Forester Bruce Bolander, Tree Distribution z Site Preparation z Care of Seedlings Before Plantings z Heeling-in Steps z How to Plant z Hand Planting z Weed Control z Protection z Additional Information SITE PREPARATION Proper site preparation is essential to your tree planting operation, and varies with the different climates and soil types. Chemical Control: On sandy soils, rough terrain, or other highly erodible sites, tillage is not recommended. Chemical weed and/or grass killers may be applied to the site in the fall or before planting in the spring. Summer Fallow: This practice is recommended on heavy soil in western Nebraska to conserve soil moisture. This may be accomplished with the aid of occasional disking, subsurface tillage, or chemicals to control weeds. -

Tree Planting Experiences in the Eastern Interior Coal Province

TREE PLANTING EXPERIENCES IN THE EASTERN INTERIOR COAL PROVINCE Paper Presented at the Symposium on Trees for Reclamation in the Eastern U.S. Lexington, Kentucky October 27-29, 1980 Charles Medvick Land Reclamation Specialist, Illinois Department of Mines and Minerals, Land Reclamation Division Route 6, Box 140-A, Marion, Illinois 62959 Abstract.--Fruit trees were planted successfully in 1918 and organized afforestation began in 1928. Profes- sional foresters had a hand in some of the very earliest planting projects. Formal reclamation research played an important role in applying science to early reclamation technology; however, considerable work has preceded the scientists. Some success has been experienced with tree planting on coal waste slurry, a problem site with uniquely adverse conditions. Some indications were found showing early Chinese Chestnut tree plantings developing into timber form trees, under some conditions. It was also observed that Chinese Chestnut trees are reproducing naturally from trees planted on mine spoils as young as 12 to 15 years of age. INTRODUCTION common to this area is generally thick uncon- solidated overburden materials lying above Subject of this paper deals with the shale, sandstone; limestone, or a combination Eastern Interior Province (E.I.P.). Though of the three, which form the balance of the the bulk of this region is in Illinois, the overburden above coals in this area. E.I.P. area extends over Southwestern Indiana and the northern part of Western Kentucky. There is considerable similarity between All of the coal mining activity in Illinois surface mining conditions in the Illinois and and Indiana is within the E.I.P.; however, Indiana unglaciated regions. -

2017 April Timber Talk

Timber Talk Newsletter of the Iowa Woodland Owners Association and Iowa Tree Farmers Association April 2017 Editor: Steve Meyer digging a hole large enough for the seedling's root PLANTING FOREST SEEDLINGS system and filling soil back around the root system From ISU Forestry Extension with sufficient compaction to ensure good root to soil contact. A tree planting bar or a mechanical Editor’s note: I thought this was timely as seedling planting is one of the things that many of us will be involved tree planter are used to increase the planting rate. in 0ver the next couple months. Be sure the slit around the seedling is closed to minimize drying and potential herbicide damage Tree planting success can be improved if several from pre-emergent herbicides. With all techniques, guidelines are followed. First and foremost, order plant at the same depth the seedling grew in the tree stock from a reputable nursery to ensure that nursery. you get quality seedlings of the kind and type For all plantings, make provisions for adequate desired. When the planting stock is received by weed control for 2-4 years. Several techniques you, carefully inspect it for damage. Inspect the provide acceptable weed control including root system looking for mold or excessive dryness. mechanical or cultivation, mulches such as wood For best results, plant seedlings as soon as chips or ground corncobs, and herbicides such as possible. The longer the time between shipment simazine, Surflan, or Goal [see page 3]. Always and planting, the greater the risk of losses. For follow label precautions and use accepted sprayer short term storage of nursery stock, unheated calibration procedures to ensure the effectiveness buildings or cellars can be used. -

Attitudes and Knowledge of Forestry by High School Agricultural Education Teachers in West Virginia

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2008 Attitudes and knowledge of forestry by high school agricultural education teachers in West Virginia Kristin R. Lockerman Friend West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Lockerman Friend, Kristin R., "Attitudes and knowledge of forestry by high school agricultural education teachers in West Virginia" (2008). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 1934. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/1934 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Attitudes and Knowledge of Forestry by High School Agricultural Education Teachers in West Virginia Kristin R. Lockerman Friend Thesis submitted to the Davis College of Agriculture, Forestry and Consumer Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Forestry David M. McGill, Ph.D., Chair Harry N. Boone, Jr., Ph.D. Deborah A. Boone, Ph.D. William N. -

Lexington, Kentucky October 27 - 29, 1980

Lexington, Kentucky October 27 - 29, 1980 sponsored by ~I TABLE OF CONTENTS Trees for Tomorrow .............1 Has Anyone Noticed that Trees Are Not Edward A. Johnson Being Planted Any Longer?. .......53 Walter D. Smith Trees for Reclamation in the Eastern United States ..............7 Revegetat ion of Surf ace-Mined Lands C. W. Moody, David T. Kimbrell in Pennsylvania ............57 G. Nevin Strock Mine Reclamation in Arkansas ........9 Floyd Durham, James G. Barnum Trees for Reclamation in the Eastern United States; A West Virginia A Look at Trees and Reclamation in Georgia 11 Perspective ..............61 Sanford P. Darby James E. Pit senbarger Reclamation with Trees in Illinois .....15 The Role of West Virginia's Division Brad Evilsiz er of Forestry ..............63 Asher W. Kelly, Jr. Using Trees on keclaimed Mined Lands in Southern Illinois ............17 Trees for Reclamation in the Eastern Jim Sandusky United States .............65 James R. White Forestry as a Reclamation Practice on Strip Mined Lands in Kansas .......21 Introduction to Pine Reforestat ion Harold G. Gallaher and Action Plan ..............69 Gary G. Naughton George N. Brooks Kentucky' s Nursery Situation ....... .25 Forestation of Surface Mines for Wildlife 71 Raymond J. Swatzyna Thomas G. Zarger Tree Planting - Strip-Mined Area in Revegetation for Aesthetics .......75 Maryland ................27 Bernard M. Slick Fred L. Bagley Tree Planting Experiences in the Eastern Reforestat ion Species Study on a Reclaimed Interior Coal Province .........85 Surface Mine in Western Maryland .... .35 Charles Medvick Jay A. Engle Direct Seeding for Forestation ......93 An Evaluation of Reclamation Tree Planting Walter H. Davidson in Southwest Virginia ......... .37 Danny R. -

Mississippi Curriculum Framework for Forestry Technology (Program CIP: 03.0401--Forest Harvesting and Production Technology)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 397 283 CE 072 168 TITLE Mississippi Curriculum Framework for Forestry Technology (Program CIP: 03.0401--Forest Harvesting and Production Technology). Postsecondary Programs. INSTITUTION Mississippi Research and Curriculum Unit for Vocational and Technical Education, State College. SPONS AGENCY Mississippi State Dept. of Education, Jackson. Office of Vocational and Technical Education. PUB DATE 30 Jul 96 NOTE 73p.; For related documents, see CE 072 162-231. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Agricultural Education; Agronomy; Behavioral Objectives; Careers; Community Colleges; Competence; *Competency Based Education; Core Curriculum; Educational Equipment; *Forestry; Forestry Occupations; *Land Use; Leadership; *Lumber Industry; State Curriculum Guides; Statewide Planning; Technical Institutes; Trees; Two Year Colleges; Vocational Education IDENTIFIERS Mississippi ABSTRACT This document, which is intended for use by community and junior colleges throughout Mississippi, contains curriculum frameworks for the course sequences in the forestry technology program cluster. Presented in the introductory section are a description of the program and suggested course sequence. Section I lists baseline competencies for the program, and section II consists of outlines for the three categories of courses in the forestry technology sequence: (1) forestry courses--forest mensuration I, survey oi forestry, forest surveying, silviculture I, applied dendrology, timber harvesting, forest mensuration II, forest protection, forest products utilization, silviculture II, special problem in forestry technology, and work-based learning;(2) related vocational-technical courses--fundamentals of microcomputer applications, applied soils (conservation and use), applied agricultural economics, mapping and topography, and fundamt tals of drafting; and (3) related academic courses--principles of accounting I, botany, and business law. -

Primary Restoration

Primary Restoration Guidance Document for Natural Resource Damage Assessment Under the Oil Pollution Act of 1990 Damage Assessment and Restoration Program August 1996 PRIMARY RESTORATION GUIDANCE DOCUMENT FOR NATURAL RESOURCE DAMAGE ASSESSMENT UNDER THE OIL POLLUTION ACT OF 1990 Prepared for the: Damage Assessment and Restoration Program National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration 1305 East-West Highway, SSMC #4 Silver Spring, Maryland 20910 Prepared by: EG&G Washington Analytical Services Center, Inc. 1396 Piccard Drive Rockville, MD 20850 Joseph Green, Contract Manager Authorship: Deborah P. French, Henry Rines, Dian Gifford, Aimee Keller, and Sharon Pavignano Applied Science Associates, Inc. 70 Dean Knauss Drive Narragansett, Rhode Island 02882 and Garry Brown, Bradly S. Ingram, Emily MacDonald, Jacqueline Quirk, and Stefan Natzke A.T. Kearney, Inc. 225 Reinekers Lane, P.O. Box 1438 Alexandria, VA 22313 and Kenneth Finkelstein Arthur D. Little, Acorn Park Cambridge, MA 02140 August 1996 DISCLAIMER This guidance document is intended to be used in the assessment of restoration of injured natural resources under the Oil Pollution Act of 1990 (OPA). This document is not regulatory in nature. Trustees are not required to use this document in order to receive a rebuttable presumption for natural resource damage assessments under OPA. NOAA would appreciate any suggestions on how this document could be made more practical and useful. Readers are encouraged to send comments and recommendations to: Eli Reinharz Damage Assessment Center National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration 1305 East-West Highway, SSMC #4, N\ORCA\x1 Silver Spring, Maryland 20910 (301) 713-3038 ext 193, phone (301) 713-4387, fax [email protected], e-mail address TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF EXHIBITS............................................................................................................. -

Planting Cypress and Tupelo Seedlings for Reforestation in Deep

Focus Series on Bottomland Swamp Forests December 2018 #BF-3 Planting Cypress and Tupelo Seedlings for Reforestation in Deep Swamps Prompt and effective reforestation after timber is harvested in deep, bottomland swamps is vital to sustain the forest resources and minimize overall landscape effects. Reforestation can be challenging in these types of swamps due to their unique characteristics including very soft, mucky soil and the presence of standing water for much of the year. This leaflet focuses on establishing seedlings to regenerate these primary tree species of focus: - Bald cypress, Taxodium distichum - Pond cypress, Taxodium ascendens - Water tupelo, Nyssa aquatica - Swamp tupelo, Nyssa biflora When considering an overall reforestation plan, you should consider incorporating techniques and tactics that promote natural regeneration coupled with targeted planting of seedlings (also known as ‘artificial’ regeneration). Successful reforestation in deep, muck swamps may take several seasons to occur. It is in the owner’s best interest to be proactive and accelerate this process where feasible to meet the desired management objectives. Forestry Leaflet #BF-2 outlines an approach for deploying natural reforestation techniques for these species. Site Factors There are two main site factors to consider when assessing reforestation options in swamps: soil and hydrology. Soil • In many of the so-called ‘deep’ swamps where cypress and tupelo often grow, the soils are mucky and often saturated at, or near, the ground surface. • It is difficult to create an opening in the soil that stays open long enough to set a seedling, and it can be difficult to pack the soil around the seedling’s roots. -

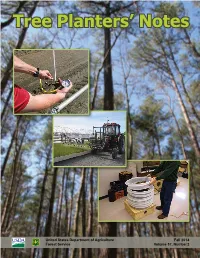

Tree Planters' Notes Volume 57, Number 2

Tree Planters’ Notes United States Department of Agriculture Fall 2014 Forest Service Volume 57, Number 2 The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C. 20250-9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Tree Planters’ Notes (TPN) is dedicated to tech- nology transfer and publication of information Dear TPN Reader relating to nursery production and outplanting of trees and shrubs for reforestation, restoration, Dear TPN Reader and conservation. TPN is sponsored by the Cooperative Forestry Staff of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Forest Once again, I’m pleased to bring you another issue of Tree Planters’ Notes, packed Service, State and Private Forestry Deputy Area, in with useful information to all of you who grow and plant trees for reforestation and Washington, DC. The Secretary of Agriculture has determined that the publication of this periodical restoration. -

L731 Planting Black Walnut

Planting Black Walnut Black walnut (Juglans nigra) is may be found in draws and along ated with cultivation and the use of the most commercially valuable tree the base of north- and east-facing heavy equipment — can hinder root in Kansas. Its chocolate-colored slopes of less than 15 percent. Black development. wood is highly desired for fine walnut grows best when crowns are The most important nutrients furniture, veneer, interior finish, exposed to full sun in an environ- for good black walnut growth are cabinets, and gun stocks. The wood ment protected from wind and available at a pH between 5 and 8, is straight grained, strong, heavy, extreme temperature variations. however, a range between 6.5 and decay resistant, easily worked with Soils. Optimum growth occurs in 7.2 is best. Most Kansas soils suit- tools, and shrinks and swells little loamy soils (both sand and silt) of able for black walnut have adequate after seasoning. Many consider the medium texture that is at least 3 feet fertility. However, it is always a nutmeats a delicacy and the ground deep. Avoid soils with restrictive good idea to test soil before planting shells are used as abrasives. layers of coarse sand, gravel, rock, since soil amendments are most Planting black walnut is a good or heavy clay. Black walnut likes practical during site preparation. For long-term investment for land- fertile, moist, but well-drained, soils a small fee, local K-State Research owners. In most cases, the cost of with high organic matter. Alternate and Extension offices can provide planting is borne by one generation streaks or blotches of yellowish soil tests. -

Tree Planting Guide

Stream Team Academy Fact Sheet #1 TREE PLANTING GUIDE An Educational Series For Stream Teams To Learn and Collect Stream Team Academy Fact Sheet Series pring is tree planting time, and many seedlings in water because the roots can #1: Tree Planting Guide SStream Teams have identified sites on be damaged. To ensure healthy seedlings, their favorite stream to plant seedlings protect them from freezing and keep them Watch for more Stream they ordered from the MDC nursery last moist during planting. Seedlings can be Team Academy Fact fall. Whether you are planting trees along planted in February as soon as the frost is Sheets coming your way your stream or for landscaping in your out of the ground. Planting later in the soon. Plan to collect the entire educational series yard, these tips will help your planting be spring results in slower growth and for future reference! successful. probable failure. When you receive your seedlings, Whether you are planting by hand or keep them in a moist, cool, shaded place using a hoe, shovel, or planting bar, before planting day. Do not store the follow these guidelines: Dig each hole to fit the root system. Set the seedling at the same depth that the tree grew in the nursery. Ensure the planting hole is deep enough so roots point downward. Planting with the roots pointing upward, J rooting, results in a dead seedling when the roots break the soil surface. Fill the hole half full of soil and tamp well. Finish filling the hole and tamp with your feet.