Lexington, Kentucky October 27 - 29, 1980

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TREE PROTECTION in Highly Urbanized Areas with Existing Green and Gray Infrastructure Conflicts (Each.) CODE 990B

ILLINOIS URBAN MANUAL PRACTICE STANDARD TREE PROTECTION In Highly Urbanized Areas with Existing Green and Gray Infrastructure Conflicts (each.) CODE 990B (Source: IN Drainage Handbook) NOTE: Only use Practice Standard Code the health and integrity of the tree 990B when there are green and gray resources on site. infrastructure conflicts and when adequate long-term monitoring of the trees exists. This standard MUST BE USED ONLY IN CONDITIONS WHERE PRACTICE CONSULTATION with a PROFESSIONAL APPLIES FORESTER or CERTIFIED ARBORIST. This standard shall be used in lieu of no DEFINITION local ordinance or in tandem with local tree protection ordinances. When The protection of individual trees from possible, IUM Practice Standard Code damage during construction operations 990A -TREE PROTECTION shall be in highly urbanized areas where there used instead of IUM Practice Standard are individual trees growing close to Code 990B. IUM Practice Standard gray urban infrastructure. Code 991- TREE PROTECTION- AUGERING Standard should be used in PURPOSE conjunction with this standard, as needed. The purpose of this practice is to reduce damage to and loss of individual trees This standard takes into consideration during construction by implementing trees next to roads and sidewalks where these pre- to post-construction tree there already exists an infrastructure protection procedures. Tree protection conflict that can be resolved without fencing around the Tree Protection compromise to either the green or gray Critical Root Zone (TPCRZ) as defined infrastructure. below along with other soil, root and tree protection measures shall be installed This practice applies on development with this standard in order to maintain sites that are highly urbanized, where 990B - 1 the green and gray infrastructure has be protected using the length of the been developed or has grown in close longest branch as the radius of the proximity and where there are individual circle. -

"Let's Talk About the Reasons We Offer FREE TRENCHER DEMONSTRATIONS

STRAIGHT TALK FROM YOUR DITCH WITCH MAN "Let's talk about the reasons we offer FREE TRENCHER DEMONSTRATIONS. "We talk a lot about the many different jobs Ditch Witch can do. But we haven't forgotten many people need to dig trench and that's all. We know if trenching is all you need to do, you don't want to pay for features you won't be using. If trenching is your business, Ditch Witch is for you! We built the world's first service line trencher and have been building the finest quality trenchers ever since. We have compact handlebar models, larger four-wheel drive trenchers and machines that can handle cross-country pipelines. And wherever your work takes you, you'll find a Ditch Witch dealer nearby with a full inventory of parts, and the professionals to keep your Ditch Witch on the job. 30-HP Model V30 — Trenching capabilities to 18" width, to 6' depth We'd like to tell you more about our trenchers. Better yet, we'd like to show you what Ditch Witch can do. We'll bring one straight to your job for a free demonstration — no obligation. "At Ditch Witch, we tell it to you straight!" Call (800) 654-6481 Toll Free for the name of the dealer nearest you. 18-HP Model J20 — 4 wheel drive, with three speed forward plus reverse transmission | 30-HP Model R30 — Trenching depths to 6' plus Modularmatic versatility Handlebar Series — Two different models available from 7-HP to 12.5-HP Ditch Witch . equipment from 7 - to 195-HP. -

Ledbury Salerooms

LEDBURY SALEROOMS Annual collective sale of VINTAGE & CLASSIC ENGINES,TRACTORS, TRACTOR SPARES,TOOLS, SEATS, MODELS, LITERATURE, ENAMEL & TIN SIGNS, AGRICULTURAL BYGONES RD SATURDAY 3 DECEMBER 10AM PROMPT 10% + VAT buyers premium. RESULTS Newmarket House, Market Street, Ledbury. Herefordshire. HR8 2AQ. Tel: 01531 631122. Fax: 01531 631818 Email: [email protected] Lot Tot No. Price Description 1 20 Box of various models, tractors, trailers, baler etc 3 30 6 Model vans & boxes, and AA car badge 4 35 7 Model lorries & boxes 5 30 6 Model cars & boxes 6 30 Model CAT 587T pipe layer boxed 7 15 Letter scales, Libra Scale Co scales & weights 8 35 JCB Brittians & Ertl models 5 9 25 Ertl 1,16 JD model A tractor 10 35 Ertl 1.16 JD Waterloo boy 2hp engine 11 65 Quantity of Dinky & other toys 12 30 Ertl JD Model R waterloo boy 13 10 Ertl Antique pump jack 14 25 Box of models including Corgi 15 30 5 Boxed Britians implements 16 15 Rare early tin plate horse drill 18 20 Charbevi tractor & driver 20 10 2 Britains horse carts 21 15 2 Corgi tractors, Ford & Massey & Britains dics, hayrack, trailer 22 25 Triang crawler 23 25 F.G. Taylor & Sons boxed windmill (farm series) 1945-52 No 531 24 55 Mamod engine & pulley 25 50 Mamod engine & pulley 26 60 Mamod steam engine SP2 27 480 Wyvern single cyclinder engine 28 60 Wilesco D455 steam engine 29 100 Wilesco D24 steam engine 30 90 Wilesco D24 steam engine 31 140 4 Engines 32 65 Mamod engine 33 50 Engine 34 50 Mamod steam engine 35 10 Japenese toys 37 520 French portable Michilin Man compressor No 7017 R. -

Postsecondary Forestry Technology

2007 Mississippi Curriculum Framework Postsecondary Forestry Technology (Program CIP: 03.0511 – Forest Technology/Technician) Direct inquiries to Debra West Director for Career and Technical Education State Board for Community and Junior Colleges 3825 Ridgewood Road Jackson, MS 39211 (601) 432-6518 [email protected] Jimmy McCully, Ph.D. Coordinator, Agricultural Education and Special Initiatives Research and Curriculum Unit P.O. Drawer DX Mississippi State, MS 39762 (662) 325-2510 [email protected] Additional copies Research and Curriculum Unit for Workforce Development Vocational and Technical Education Attention: Reference Room and Media Center Coordinator P.O. Drawer DX Mississippi State, MS 39762 http://cia.rcu.msstate.edu/curriculum/download.asp (662) 325-2510 Published by Office of Vocational Education and Workforce Development Mississippi Department of Education Jackson, MS 39205 Research and Curriculum Unit for Workforce Development Vocational and Technical Education Mississippi State University Mississippi State, MS 39762 The Mississippi Department of Education, Office of Vocational Education and Workforce Development does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin, sex, age, or disability in the provision of educational programs and services or employment opportunities and benefits. The following office has been designated to handle inquiries and complaints regarding the non-discrimination policies of the Mississippi Department of Education: Director, Office of Human Resources, Mississippi Department -

Wildlife: Regional Forester Sensitive Species (Rfss)-Plants

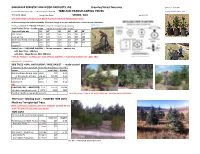

WILDLIFE: REGIONAL FORESTER SENSITIVE SPECIES (RFSS)-PLANTS (1) Overview Several sensitive plant projects involving monitoring were planned in 2005. These projects were all either habitat improvement projects or monitoring of a mitigation that was required for another project. However, due either to lack of a sufficient burn window or to litigation, only one of these projects was implemented: Kawishiwi Admin Site Botrychium Transplant. Lack of a burn window prevented treatments from being implemented for a Virginia EIS moonwort project and a Trygstad Sale barren strawberry project, and litigation of the Tomahawk EA prevented implementation of a Botrychium habitat improvement project. Baseline monitoring has been conducted at all of these project sites, and follow – up monitoring would be conducted after treatments occur. For the Kawishiwi Admin Site Botrychium Transplant, a large population of the rare matricary grapefern (Botrychium matricariifolium) was growing where the parking lot was planned for the new Admin Site. To mitigate impacts from the project, we attempted to transplant individuals to 2 nearby sites using a tree spade as well as by hand using a shovel. Transplanting occurred in Fall 2004, and monitoring occurred in Summer 2005. Survival of individuals was measured in plots. 65% of transplanted individuals survived across all plots. Monitoring will be repeated in 2006. 1) Matricary grapefern population that will 2) Tree spade in process of transplanting 3) Completed transplant plug be impacted by parking lot construction WL. RFSS-Plants 149 (2) Monitoring Activities Monitoring Question To what extent is Forest management contributing to the conservation of sensitive species and moving toward short term (10-20 years) and long-term (100 years) objectives for their habitat conditions? Monitoring Driver(s): Objective. -

2014 June Timber Talk

Timber Talk Newsletter of the Iowa Woodland Owners Association June 2014 Editor: Steve Meyer moving a couple of six year old Chestnut seedlings. We 2014 SPRING FIELD DAY REVIEW struggled with one tree as the ground was still a little Submitted by Paul Millice, IWOA Secretary Nancy and I had the honor of hosting the IWOA Spring IN THIS ISSUE Field Day on our acreage this year. We had over eighty 2014 Field Day Review p. 1 folks for the day. We started out in the beautiful Fall field day announcement p. 2 Johnson County Extension facility with a number of Legislative Report p. 3 learning seminars. Coalition for Iowa’s Woodlands and Trees update p. 3 We would like to thank the following folks for their Safety Corner p. 5 presentations: IWOA Board Minutes p. 6 Patrick O’Malley for his two hour session on 2014 Tree Farmer of the Year p. 6 Apple tree grafting. Utilizing a Large Acorn Crop p. 7 Jim Ward for his session on Habitat Deer Depredation Meeting Report …. p. 8 Hiring Professional Tree Services p. 9 Management for Whitetails At the Woodpile p. 9 Dr. Jessie Randall on Maple Syrup Making Timber Talk Classifieds p. 11 Bill Bunger IDNR for information on the Depredation Program. hard. I then demonstrated planting seedlings using my Greg Redlin for The Chain Saw Sharpening earth auger and talked about the history and our tree training and donating a MS 170 for the door protections efforts to include tree shelters, tree cages prize. and electric fencing to control deer damage to our Bob Petrzelka Consulting Forester for the trees. -

EC82-1738 Tree Planting Guide

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Historical Materials from University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension Extension 1982 EC82-1738 Tree Planting Guide William R. Lovett University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Bruce E. Bolander University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/extensionhist Part of the Agriculture Commons, and the Curriculum and Instruction Commons Lovett, William R. and Bolander, Bruce E., "EC82-1738 Tree Planting Guide" (1982). Historical Materials from University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension. 836. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/extensionhist/836 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Extension at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Historical Materials from University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Nebraska Cooperative Extension EC82-1738 Tree Planting Guide by Bill Lovett, Tree Improvement Forester Bruce Bolander, Tree Distribution z Site Preparation z Care of Seedlings Before Plantings z Heeling-in Steps z How to Plant z Hand Planting z Weed Control z Protection z Additional Information SITE PREPARATION Proper site preparation is essential to your tree planting operation, and varies with the different climates and soil types. Chemical Control: On sandy soils, rough terrain, or other highly erodible sites, tillage is not recommended. Chemical weed and/or grass killers may be applied to the site in the fall or before planting in the spring. Summer Fallow: This practice is recommended on heavy soil in western Nebraska to conserve soil moisture. This may be accomplished with the aid of occasional disking, subsurface tillage, or chemicals to control weeds. -

Tree Transplanting Price List 4-16-21.Xlsx

GREENLEAF FORESTRY AND WOOD PRODUCTS, INC. Greenleaf Forest Nurseries prices.rev. April 2021 11424 Black Forest Road, Bldg. 5, Colorado Springs, CO 80908 TREE AND TRANSPLANTING PRICES www.greenleafforestry.com 719-429-4404 Locally Colo. Grown SPRING, 2021 rev 4-25-21 we work with tree donors in Black Forest to reduce restoration costs All trees are subject to limited availability. Prices may change at any time without notice. Call for current information., All Sales are SUBJECT TO TREE SIZES AVAILABLE -- Discounts may apply to large quantities. Small Potted Trees -- locally grown Height in inches Taller= more $ Trees in #5 size pot 18" 24" 30" 36" 42" 48" Blue Spruce $35 $40 $45 $50 $60 $70 Austrian Pine $35 $40 $45 $50 $55 $65 Bristlecone Pine& best BlueSpr$45 $50 $55 $65 $75 $85 White Fir $45 $55 $65 $75 $85 $95 Douglas Fir $35 $40 $45 $50 Potted Tree -- PLANTING SERVICES -- 10 tree minimum -- cost per tree with Basic Dish, $30/tree with Dish + Weed Barrier Mat, $40/tree TYPICAL PROJECT: 10 TREES 24" BLUE SPRUCE $40/TREE + PLANTING W/MAT $40 = $80/ TREE B&B dug trees, ready to plant B&B TREES = BALL AND BURLAP / WIRE BASKET -- ready to plant dug and stored at our Black Forest Nursery (Black Forest Rd) Species cost/ foot Heights Blue and Green Spruce, pine, good $40 6-12' or Douglas-fir, white fir s/prem $45-55 6-12' Bristlecone pine good $55 6-12' Limber pine good $40 6-12' B&B PLANTING COST -- B&B TREES1-2 TRs 3-6 TRs 7(+)TRs Including tree delivery, each $275 $225 $200 (hand, or machine tree spade assisted) Typical b&b project: 5 trees 8' tall, good, = $320/ tree + $225/tree planting = $545 each. -

Southern Illinois University Campus Tree Care Plan

Southern Illinois University Campus Tree Care Plan I. The purpose of the SIU campus tree care plan is to identify the policies, procedures, and practices that are used in establishing, protecting, maintaining, and removing trees on the SIU campus. The overall goal of the plan is to ensure a safe, attractive, and sustainable campus urban forest. The specific objectives of the plan are: Ensure proper species selection, high-quality nursery stock acquisition, and industry- consensus planting procedures. Promote species diversity and proper age structure in the tree population. Protect high-value campus trees during construction and renovation projects. Promote tree health and safety utilizing International Society of Arboriculture (ISA) best management practices when maintaining campus trees, and the American National Standards Institute’s (ANSI) safety standards. Ensure that trees are reasonably replaced when there is mortality due to weather, pest infestations, injury, or construction displacement. Encourage campus community members to respect and value the campus urban forest. Public outreach that promotes urban forestry; awareness, sustainability, and serves as a model urban forest for communities in the Southern Illinois region. II. The responsibility of the Campus Tree Care Plan rests with Southern Illinois University Physical Plant under the direction of the Superintendent of Grounds and/or the University Certified Arborist. 1 | P a g e III. The Campus Tree Advisory Committee is currently composed of: Committee Members Groups -

Baumalight Nomad Tree Spade

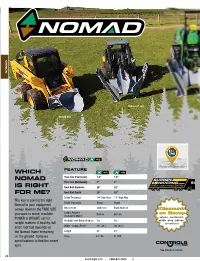

NOMAD Nomad ST 330 Nomad X4S X 4S Find your closest dealer online FEATURE WHICH X 4S X 4B NOMAD Tree Size (Evergreen) 1.5” 1.5” Tree Size (Hardwood) 1” 1” IS RIGHT Root Ball Diameter 28” 28” FOR ME? Root Ball Depth 20” 20” Blade Thickness 1/4” High Alloy 1/4” High Alloy The key to pairing the right Blade Truncation Sharp Sharp Nomad to your equipment comes down to the TREE SIZE Attachment Skid Steer Blank Weld-On Loader Adapter you want to move, machine Bolt-on Bolt-on Availability/Model POWER & WEIGHT, carrier Available with Blank Weld-on Yes Yes weight matters. A healthy, full sized root ball depends on Width - Scoop (Plate)* 28” (44”) 28” (44”) the Nomad frame remaining Length 43” 43” on the ground. Compare Price $1,196 $1,000 specifi cations to fi nd the sweet spot. See website for details 24 baumalight.com - 1-866-820-7603 U NOMAD Nomad ST 440 Nomad SS 330 Rough Neck 586 FRONT MOUNT baumalight.com/media FEATURE ST ST SS ST ST 324 330 330 440 650 Tree Size (Evergreen) 2” 3” 3” 4” 5” 3.5” 4” 4.5” 5” 5.5” Tree Size (Hardwood) 1.5” 2.5” 2.5” 3” 4” 3” 3.5” 4” 4.5” 5” Root Ball Diameter 24” 30” 30” 40” 50” 34” 38” 44” 48” 50” Root Ball Depth 23” 29” 29” 30” 43” 23” 27” 31” 38” 45” Opening (Width) 20” 23” 60” 52” 47” Blade Angle (Degrees) 25° 25° 25° 25° 25° 25 25 25 25 25 No. -

Equipment Rental Rates Schedule C

Equipment Rental Rates Schedule C REPORT 375 Equipment Rental Rates (Schedule C) Report 375 EFFECTIVE JANUARY 1, 2020 THROUGH DECEMBER 31, 2020 Hourly equipment rental rates are based on the following data reported by County Road Commissions on the county equipment questionnaires: 1. Expenses: Direct repair, indirect repair and storage, operating and depreciation. 2. Hours of equipment operation. These rates were computed by using 2018 actual expenses of County Road Commissions, plus a factor for estimated increased costs between 2018 and 2020. Counties possessing a State Trunk Line Maintenance Contract will be reimbursed at these rates. However, a county may elect to use a modified rate for reimbursement, in accordance with subsection 15(F) of the contract. Table for Computing Equipment Depreciation 5-Year Depreciation 10.100, 10.200, 12.300, 12.301, 12.302, 12.303, 12.304, 12.305, 12.306, 12.307, 12.400, 12.501, 12.502, 12.503, 12.504, 31.100, 31.400, 62.500, 63.420, 63.430, 63.500, 63.510, 63.550, 63.554, 63.560, 63.565, 63.570, 63.575, 63.600, 63.700, 63.701, 63.702, 63.801, 63.802, 81.110, 81.120, 81.130, 81.251, 81, 252, 81.253, 81.254, 81.255, 81.256, 81.257, 81.258, 81.261, 81.262, 82.110, 82.119, 82.120, 82.121, 82.122 82.128, 82.130, 82.140, 95.35 0 Fiscal Year Depreciation Years Calendar Year 10/1 – 9/30 Month Year of Month Purchase Month 2nd Year 3rd Year 4th Year 5th Year 6th Year January October 1 33.00% 27.00% 20.00% 13.00% 7.00% 0.00% February November 2 30.25% 27.50% 20.58% 13.59% 7.50% 0.58% March December 3 27.50% 28.00% 21.17% 14.16% 8.00% 1.17% April January 4 24.75% 28.50% 21.75% 14.75% 8.50% 1.75% May February 5 22.00% 29.00% 22.33% 15.34% 9.00% 2.33% June March 6 19.25% 29.50% 22.92% 15.91% 9.50% 2.92% July April 7 16.50% 30.00% 23.50% 16.50% 10.00% 3.50% August May 8 13.75% 30.50% 24.08% 17.09% 10.50% 4.08% September June 9 11.00% 31.00% 24.67% 17.66% 11.00% 4.67% October July 10 8.25% 31.50% 25.25% 18.25% 11.50% 5.25% November August 11 5.50% 32.00% 25.83% 18.84% 12. -

Tree Planting Experiences in the Eastern Interior Coal Province

TREE PLANTING EXPERIENCES IN THE EASTERN INTERIOR COAL PROVINCE Paper Presented at the Symposium on Trees for Reclamation in the Eastern U.S. Lexington, Kentucky October 27-29, 1980 Charles Medvick Land Reclamation Specialist, Illinois Department of Mines and Minerals, Land Reclamation Division Route 6, Box 140-A, Marion, Illinois 62959 Abstract.--Fruit trees were planted successfully in 1918 and organized afforestation began in 1928. Profes- sional foresters had a hand in some of the very earliest planting projects. Formal reclamation research played an important role in applying science to early reclamation technology; however, considerable work has preceded the scientists. Some success has been experienced with tree planting on coal waste slurry, a problem site with uniquely adverse conditions. Some indications were found showing early Chinese Chestnut tree plantings developing into timber form trees, under some conditions. It was also observed that Chinese Chestnut trees are reproducing naturally from trees planted on mine spoils as young as 12 to 15 years of age. INTRODUCTION common to this area is generally thick uncon- solidated overburden materials lying above Subject of this paper deals with the shale, sandstone; limestone, or a combination Eastern Interior Province (E.I.P.). Though of the three, which form the balance of the the bulk of this region is in Illinois, the overburden above coals in this area. E.I.P. area extends over Southwestern Indiana and the northern part of Western Kentucky. There is considerable similarity between All of the coal mining activity in Illinois surface mining conditions in the Illinois and and Indiana is within the E.I.P.; however, Indiana unglaciated regions.