Experience, Narrative and Gender in Early Modern French Medicine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Livres De Médecine Incunables : – Bonhomme

KAPANDJI MORHANGE Commissaires Priseurs à Drouot MERcredi 8 juillet 2009 – Hôtel DROUOT Paris - Hôtel Drouot Paris Mercredi 8 juillet 2009 Mercredi ORHANGE M APANDJI K LIVRES ANCIENS ET MODERNES Incunables – Médecine 46 bis, passage Jouffroy – 75 009 Paris Tél : 01 48 24 26 10 • Fax : 01 48 24 26 11 • E-mail : [email protected] MATÉRIEL CHIRURGICAL 06_COUV_8_juill_09_KM.indd 1 11/06/09 20:17:51 150 En couverture lot 71, en 2e de couverture lot 196, 4e de couverture lot 210. 06_COUV_8_juill_09_KM.indd 2 11/06/09 20:18:01 KAPANDJI MORHANGE Ghislaine KAPANDJI et Élie MORHANGE, Commissaires-Priseurs Agrément 2004-508 – RCS Paris B 477 936 447 46 bis, passage Jouffroy – 75 009 Paris [email protected] site www.kapandji-morhange.com 5ÊMr'BY VENTES AUX ENCHERES PUBLIQUES HÔTEL DROUOT – SALLE 7 9, Rue Drouot – 75 009 Paris Mercredi 8 juillet 2009 à 14h LIVRES ANCIENS ET MODERNES - LIVRES DE MÉDECINE INCUNABLES : – BONHOMME. Traité de la céphalotomie – BOURGERY & TORQUEMADA. Expositio super regulam – SAINT- JACOB. Anatomie descriptive – CRUVEILHIER. Anatomie BERNARD. Liber meditationum – MARSILIO FICIN. De pathologique – DIONIS. Cours D’Opérations de Chirurgie triplici vita – SAINT-ANSELME. Opuscula – DE PLOVE. – GILBERT. Histoire médicale de l’armée Française à Saint- Vita christi – THEMESVAR. Stellarium corone. Domingue – ESTIENNE. La Dissection des parties du corps e e humain – FAUCHARD. Le chirurgien dentiste – FEIGEL. LIVRES DU XVI AU XX : Atlas d’Obstétrique – GALIEN. Epitomes – GUYON KRANTZ. Saxonia – ERASME. Parabolae sive similia – DOLOIS. Le cours de médecine – HALLER. Deux mémoires ORUS APOLLO. De la signification des hiéroglyphes – sur le mouvement du sang – HIGHMORE. Corporis humani BOUCHET. -

This Paper Is a Descriptive Bibliography of Thirty-Three Works

Jennifer S. Clements. A Descriptive Bibliography of Selected Works Published by Robert Estienne. A Master’s Paper for the M.S. in L.S degree. March, 2012. 48 pages. Advisor: Charles McNamara This paper is a descriptive bibliography of thirty-three works published by Robert Estienne held by the Rare Book Collection of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The paper begins with a brief overview of the Estienne Collection followed by biographical information on Robert Estienne and his impact as a printer and a scholar. The bulk of the paper is a detailed descriptive bibliography of thirty-three works published by Robert Estienne between 1527 and 1549. This bibliography includes quasi- facsimile title pages, full descriptions of the collation and pagination, descriptions of the type, binding, and provenance of the work, and citations. Headings: Descriptive Cataloging Estienne, Robert, 1503-1559--Bibliography Printing--History Rare Books A DESCRIPTIVE BIBLIOGRAPHY OF SELECTED WORKS PUBLISHED BY ROBERT ESTIENNE by Jennifer S. Clements A Master’s paper submitted to the faculty of the School of Information and Library Science of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Library Science. Chapel Hill, North Carolina March 2012 Approved by _______________________________________ Charles McNamara 1 Table of Contents Part I Overview of the Estienne Collection……………………………………………………...2 Robert Estienne’s Press and its Output……………………………………………………2 Part II -

Template EUROVISION 2021

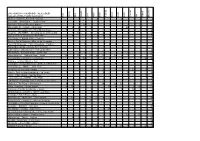

Write the names of the players in the boxes 1 to 4 (if there are more, print several times) - Cross out the countries that have not reached the final - Vote with values from 1 to 12, or any others that you agree - Make the sum of votes in the "TOTAL" column - The player who has given the highest score to the winning country will win, and in case of a tie, to the following - Check if summing your votes you’ve given the highest score to the winning country. GOOD LUCK! 1 2 3 4 TOTAL Anxhela Peristeri “Karma” Albania Montaigne “ Technicolour” Australia Vincent Bueno “Amen” Austria Efendi “Mata Hari” Azerbaijan Hooverphonic “ The Wrong Place” Belgium Victoria “Growing Up is Getting Old” Bulgaria Albina “Tick Tock” Croatia Elena Tsagkrinou “El diablo” Cyprus Benny Christo “ Omaga “ Czech Fyr & Flamme “Øve os på hinanden” Denmark Uku Suviste “The lucky one” Estonia Blind Channel “Dark Side” Finland Barbara Pravi “Voilà” France Tornike Kipiani “You” Georgia Jendrick “I Don’t Feel Hate” Germany Stefania “Last Dance” Greece Daði og Gagnamagnið “10 Years” Island Leslie Roy “ Maps ” Irland Eden Alene “Set Me Free” Israel 1 2 3 4 TOTAL Maneskin “Zitti e buoni” Italy Samantha Tina “The Moon Is Rising” Latvia The Roop “Discoteque” Lithuania Destiny “Je me casse” Malta Natalia Gordienko “ Sugar ” Moldova Vasil “Here I Stand” Macedonia Tix “Fallen Angel” Norwey RAFAL “The Ride” Poland The Black Mamba “Love is on my side” Portugal Roxen “ Amnesia “ Romania Manizha “Russian Woman” Russia Senhit “ Adrenalina “ San Marino Hurricane “LOCO LOCO” Serbia Ana Soklic “Amen” Slovenia Blas Cantó “Voy a quedarme” Spain Tusse “ Voices “ Sweden Gjon’s Tears “Tout L’Univers” Switzerland Jeangu Macrooy “ Birth of a new age” The Netherlands Go_A ‘Shum’ Ukraine James Newman “ Embers “ United Kingdom. -

Estienne's La Dissection

Erika Delbecque Section name Special Collections Services Estienne’s La dissection des parties du corps humain Special Collections featured item for August 2014 by Erika Delbecque, former Liaison Librarian for Pharmacy and Mathematics. Charles Estienne, La dissection des parties du corps humain divisee en trois livres. Paris: chez Simon de Colines, 1546. Item from the Cole Library COLE--X092F/02, University of Reading Special Collections Services. Charles Estienne’s La dissection des parties du corps humain [see title-page shown left] is one of the great illustrated anatomical works of the sixteenth century. It offers a fine example of the accomplishments and innovations of the Parisian printing houses of this period, and its full-page woodcuts have fascinated readers to this day. Charles Estienne (c. 1504-1564) was a French physician who conceived of this work when he was still a medical student in Padua. It was at this time that he also met Étienne de la Rivière, the surgeon who would carry out the dissections that provided the basis for the book’s illustrations, and who is likely to have contributed to their design. As the stepson of Simon de Colines, Charles Estienne was able to have his work ©University of Reading 2014 Page 1 published by one of the greatest printing houses in France. De Colines’ influential innovations in the design and type of French printing can also be seen in La Dissection, such as the clean layout of the page and the use of italic font, in which de Colines, a former type- cutter, followed Italian models. -

The Development of the Spa in Seventeenth-Century France

Medical History, Supplement No. 10, 1990, 23-47. THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE SPA IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY FRANCE L. W. B. Brockliss THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE SPA In the Anglo-Saxon world the enthusiasm of the twentieth-century Frenchman for imbibing his country's mineral waters is proverbial. It is surprising, therefore, to discover that the French contribution to the resuscitation of the spa in the era of the Renaissance was minimal. For most ofthe sixteenth century, the nation that has given mankind the waters of Vichy and Evian (to name but two) was largely unmoved by the fad for the hot-spring and the mineral bath that swept the Italian peninsula, crossed the Alps into the territory of the Holy Roman Empire, and penetrated even our own shores. It was not that France's future spas were undiscovered, for many had a Romano-Gallic provenance. It was rather that the therapeutic potential of mineral waters remained unrecognized by the Galenic medical establishment and hence by the large majority of the court, aristocracy, and urban elite who formed their clients. Significantly, when Andreas Baccius published the first general guide to the spas of Europe in 1571 he had little to say about France. Passing reference was made to several Roman foundations but only the virtues of Bourbon-Lancy were described in detail.1 Significantly, too, the only member of the French royal family who definitely did take the waters in the first three-quarters of the sixteenth century was united by marriage to the house of Navarre and patronized, as did her daughter later, the springs of Beam, not those of France.2 The situation first began to change in the 1 580s when a number of local physicians started to promote the waters adjacent to the towns in which they plied their profession. -

![Montaigne's Unknown God and Melville's Confidence-Man -In Memoriam]Ohn Spencer Hill (1943-1998)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7141/montaignes-unknown-god-and-melvilles-confidence-man-in-memoriam-ohn-spencer-hill-1943-1998-977141.webp)

Montaigne's Unknown God and Melville's Confidence-Man -In Memoriam]Ohn Spencer Hill (1943-1998)

CAMILLE R. LA Bossr:ERE The World Revolves Upon an I: Montaigne's Unknown God and Melville's Confidence-Man -in memoriam]ohn Spencer Hill (1943-1998) Les mestis qui ont ... le cul entre deux selles, desquels je suis ... I The mongrel! sorte, of which I am one ... sit betweene two stooles -Michel de Montaigne, "Des vaines subtilitez" I "Of Vaine Subtilties" Deus est anima brutorum. -Oliver Goldsmith, "The Logicians Refuted" YEA AND NAY EACH HATH HIS SAY: BUT GOD HE KEEPS THF MTDDT.F WAY -Herman Melville, "The Conflict of Convictions" T ATE-MODERN SCHOLARLY accounts of Montaigne and his L oeuvre attest to the still elusive, beguilingly ironic character of his humanism. On the one hand, the author of the Essais has in vited recognition as "a critic of humanism, as part of a 'Counter Renaissance'."' The wry upending of such vanity as Protagoras served to model for Montaigne-"Truely Protagoras told us prettie tales, when he makes man the measure of all things, who never knew so much as his owne," according to the famous sentence 1 Peter Burke, Montaigne (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1981) 11. 340 • THE DALHOUSIE REvlEW from the "Apologie of Raimond Sebond"2-naturally comes to mind when he is thought of in this way (Burke 12). On the other hand, Montaigne has been no less justifiably recognized by a long line of twentieth-century commentators3 as a major contributor to the progress of an enduring philosophy "qui fait de l'homme, selon la tradition antique, la valeur premiere et vise a son plein epa nouissement. -

In Retrospect: Fernel's Physiologia

OPINION NATURE|Vol 456|27 November 2008 in part from viewing our own world through Imprisoned by intelligence the distorted fairground mirror that Stephen- son establishes. The language is English with a Anathem harbour dangerous levels of intelligence. twist: the word devout morphs to avout, friar by Neal Stephenson Rather, they repopulate their numbers with to fraa, sister to suur. Euphemistic manage- Atlantic Books/William Morrow: 2008. unwanted orphans and those with abilities. ment speak is bullshyte and a caste of scathing 800 pp/960 pp. £18.99/$29.95 As the avout go about their rituals, the Sæcu- computer technicians is known as the Ita. The lar world might as well be another planet: its distortions are reflected in scientific concepts The divide between science and society is inhabitants chatter on ‘jeejahs’ (mobile phones) as well: Occam’s razor becomes Gardan’s Steel- extrapolated to the extreme in Neal Stephenson’s and surf the ‘Reticulum’ (Internet) when not yard. And the great scientific figures of Earth novel Anathem. The author, who is well cheering on sports teams and growing obese get their Arbre avatars: Plato appears as Protas, regarded for his vision of science in contempo- on sugary drinks. The two worlds mingle only Socrates as Thelenes and Archimedes as Carta. rary and historical settings, creates in his latest in strictly controlled circumstances, such as at As with any decent distortion, the author leaves work the fictional planet Arbre, which parallels an annual goodwill festival and in avout-run unexplained many areas of Arbrean society and Earth in the very far future. -

P E Ti Is Tv Á N O Rs I L Á S Z Ló L E V I a Ttila B E Tti P . R O B I

n e i s l b ó l e m n l i i o i i z u a f o z i i á i t s l b s t i t R ESC HUNGARY RAJONGÓI TALÁLKOZÓ c b s v ó s i v z t t t r s o e t e . r i s a á e s m 2021-08-28 HELYSZÍNI SZAVAZÁS P I O L L A B P E Z R T I P Ö Albánia – Anxhela Peristeri – Karma 3 2 1 3 9 Ausztrália – Montaigne – Technicolour 5 5 Ausztria – Vincent Bueno – Amen 10 2 2 14 Azerbajdzsán – Efendi – Mata Hari 1 1 5 8 7 10 6 38 Belgium – Hooverphonic – The Wrong Place 6 4 3 6 19 Bulgária – VICTORIA – Growing Up Is Getting Old 7 10 7 7 6 4 41 Ciprus – Elena Tsagrinou – El Diablo 3 4 3 3 4 3 2 22 Csehország – Benny Cristo – omaga 0 Dánia – Fyr & Flamme – Øve os på hinanden 1 1 Egyesült Királyság – James Newman – Embers 5 6 1 12 Észak-Macedónia – Vasil – Here I Stand 0 Észtország – Uku Suviste – The Lucky One 7 4 11 Finnország – Blind Channel – Dark Side 2 2 8 12 Franciaország – Barbara Pravi – Voilà 10 12 12 12 12 12 4 3 2 79 Görögország – Stefania – Last Dance 12 4 5 2 6 10 39 Grúzia – Tornike Kipiani – You 0 Hollandia – Jeangu Macrooy – Birth of a New Age 8 7 4 19 Horvátország – Albina – Tick-Tock 7 2 8 17 Írország – Lesley Roy – Maps 2 5 12 8 27 Izland – Daði og Gagnamagnið – 10 Years 7 6 3 5 1 22 Izrael – Eden Alene – Set Me Free 1 3 2 6 Lengyelország – RAFAŁ – The Ride 8 7 15 Lettország – Samanta Tīna – The Moon Is Rising 1 1 Litvánia – The Roop – Discoteque 4 5 8 10 10 10 4 51 Málta – Destiny – Je me casse 8 10 12 4 6 10 50 Moldova – Natalia Gordienko – Sugar 5 10 8 23 Németország – Jendrik – I Don’t Feel Hate 0 Norvégia – TIX – Fallen Angel 0 Olaszország – Måneskin -

Descriptions of Sections

Fall 2009 LEH300-LEH301 Descriptions LEH300 Anderson, Jazz and the Improvised Arts A history of jazz music from New Orleans to New York is coupled with an examination James of improvisation in the arts. The class will investigate form and free creativity as applied to jazz, music from around the world, the visual arts, drama, and literature. LEH300 Ansaldi, The Doctor-Patient Relationship: In this course, participants will explore the complexities of the doctor-patient Pamela Viewed through Art and Science relationship by examining selected works of literature, medicine, psychology and art. To the doctor, illness is an analysis of blood tests, radiological images and clinical observations. To the patient, illness is a disrupted life. To the doctor, the disease process must be measured and charted. To the patient, disease is unfamiliar terrain—he or she looks to the doctor to provide a compass. The doctor may give directions, but the patient for various reasons may not follow them. Or, the doctor may give the wrong directions, leaving the patient to wander in circles, feeling lost and alone. Sometimes two doctors can give identical protocols to the same patient, but only one doctor can provide a cure. The surgeon wants to cut out the injured part; the patient wants to retain it at any cost. The physician diagnoses with a linear understanding of illness; the patient may see the sequencing of events leading up to the illness in a different order, which might lead to a different diagnosis. The twists and turns of doctor-patient communication can be dizzying…and the patient goes from doctor to doctor seeking clarity and a possible cure. -

Cat68 FINAL with Edits.Indd

PHILLIP J. PIRAGES J. PHILLIP PHILLIP J. PIRAGES Catalogue 68 SIGNIFICANT BOOKS IN NOTABLE BINDINGS CATALOGUE 68 CATALOGUE Items Pictured on the Front Cover 35 19 18 27 4 2 31 42 1 20 Items Pictured on the Back Cover 9 20 6 38 33 15 25 16 26 30 38 37 39 21 36 To identify items on the front and back covers, lift this flap up and to the right, then close the cover. Catalogue 68: Significant Books in Notable Bindings Please send orders and inquiries to the above physical or electronic addresses, and do not hesitate to telephone at any time. If you telephone while no one is in the office to receive your call, automatic equipment will take your message. We would be happy to have you visit us, but please make an appointment so that we are sure to be here. In addition, our website is always open. Prices are in American dollars. Shipping costs are extra. We try to build trust by offering fine quality items and by striving for precision of description because we want you to feel that you can buy from us with confidence. As part of this effort, we want you to understand that your satisfaction is unconditionally guaranteed. If you buy an item from us and are not satisfied with it, you may return it within 30 days of receipt for a refund, so long as the item has not been damaged. Significant portions of the text of this catalogue were written by Cokie Anderson, Kaitlin Manning, and Garth Reese. -

2021 Country Profiles

Eurovision Obsession Presents: ESC 2021 Country Profiles Albania Competing Broadcaster: Radio Televizioni Shqiptar (RTSh) Debut: 2004 Best Finish: 4th place (2012) Number of Entries: 17 Worst Finish: 17th place (2008, 2009, 2015) A Brief History: Albania has had moderate success in the Contest, qualifying for the Final more often than not, but ultimately not placing well. Albania achieved its highest ever placing, 4th, in Baku with Suus . Song Title: Karma Performing Artist: Anxhela Peristeri Composer(s): Kledi Bahiti Lyricist(s): Olti Curri About the Performing Artist: Peristeri's music career started in 2001 after her participation in Miss Albania . She is no stranger to competition, winning the celebrity singing competition Your Face Sounds Familiar and often placed well at Kënga Magjike (Magic Song) including a win in 2017. Semi-Final 2, Running Order 11 Grand Final Running Order 02 Australia Competing Broadcaster: Special Broadcasting Service (SBS) Debut: 2015 Best Finish: 2nd place (2016) Number of Entries: 6 Worst Finish: 20th place (2018) A Brief History: Australia made its debut in 2015 as a special guest marking the Contest's 60th Anniversary and over 30 years of SBS broadcasting ESC. It has since been one of the most successful countries, qualifying each year and earning four Top Ten finishes. Song Title: Technicolour Performing Artist: Montaigne [Jess Cerro] Composer(s): Jess Cerro, Dave Hammer Lyricist(s): Jess Cerro, Dave Hammer About the Performing Artist: Montaigne has built a reputation across her native Australia as a stunning performer, unique songwriter, and musical experimenter. She has released three albums to critical and commercial success; she performs across Australia at various music and art festivals. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 04 April 2018 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: O'Brien, John (2015) 'A book (or two) from the Library of La Bo¡etie.',Montaigne studies., 27 (1-2). pp. 179-191. Further information on publisher's website: https://classiques-garnier.com/montaigne-studies-2015-an-interdisciplinary-forum-n-27-montaigne-and-the-art- of-writing-a-book-or-two-from-the-library-of-la-boetie.html Publisher's copyright statement: Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk A Book (or Two) from the Library of La Boétie John O’Brien The copy of the Greek editio princeps of Cassius Dio, now in Eton College, has long been recognized as formerly belonging to Montaigne (figure 1).1 It bears his signature in the usual place and in his usual style.