Ayn Rand's Reclamation of Romantic Architecture by Wyatt Mcnamara

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ayn Rand? Ayn Rand Ayn

Who Is Ayn Rand? Ayn Rand Few 20th century intellectuals have been as influential—and controversial— as the novelist and philosopher Ayn Rand. Her thinking still has a profound impact, particularly on those who come to it through her novels, Atlas Shrugged and The Fountainhead—with their core messages of individualism, self-worth, and the right to live without the impositions of others. Although ignored or scorned by some academics, traditionalists, pro- gressives, and public intellectuals, her thought remains a major influence on Ayn Rand many of the world’s leading legislators, policy advisers, economists, entre- preneurs, and investors. INTRODUCTION AN Why does Rand’s work remain so influential? Ayn Rand: An Introduction illuminates Rand’s importance, detailing her understanding of reality and human nature, and explores the ongoing fascination with and debates about her conclusions on knowledge, morality, politics, economics, government, AN INTRODUCTION public issues, aesthetics and literature. The book also places these in the context of her life and times, showing how revolutionary they were, and how they have influenced and continue to impact public policy debates. EAMONN BUTLER is director of the Adam Smith Institute, a leading think tank in the UK. He holds degrees in economics and psychology, a PhD in philosophy, and an honorary DLitt. A former winner of the Freedom Medal of Freedom’s Foundation at Valley Forge and the UK National Free Enterprise Award, Eamonn is currently secretary of the Mont Pelerin Society. Butler is the author of many books, including introductions on the pioneering economists Eamonn Butler Adam Smith, Milton Friedman, F. -

The Futurist Moment : Avant-Garde, Avant Guerre, and the Language of Rupture

MARJORIE PERLOFF Avant-Garde, Avant Guerre, and the Language of Rupture THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS CHICAGO AND LONDON FUTURIST Marjorie Perloff is professor of English and comparative literature at Stanford University. She is the author of many articles and books, including The Dance of the Intellect: Studies in the Poetry of the Pound Tradition and The Poetics of Indeterminacy: Rimbaud to Cage. Published with the assistance of the J. Paul Getty Trust Permission to quote from the following sources is gratefully acknowledged: Ezra Pound, Personae. Copyright 1926 by Ezra Pound. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Ezra Pound, Collected Early Poems. Copyright 1976 by the Trustees of the Ezra Pound Literary Property Trust. All rights reserved. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Ezra Pound, The Cantos of Ezra Pound. Copyright 1934, 1948, 1956 by Ezra Pound. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Blaise Cendrars, Selected Writings. Copyright 1962, 1966 by Walter Albert. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 1986 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 1986 Printed in the United States of America 95 94 93 92 91 90 89 88 87 86 54321 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Perloff, Marjorie. The futurist moment. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Futurism. 2. Arts, Modern—20th century. I. Title. NX600.F8P46 1986 700'. 94 86-3147 ISBN 0-226-65731-0 For DAVID ANTIN CONTENTS List of Illustrations ix Abbreviations xiii Preface xvii 1. -

Ayn Rand and Youth During the 1960S

UC Berkeley The Charles H. Percy Undergraduate Grant for Public Affairs Research Papers Title Radicals for Capitalism: Ayn Rand and Youth during the 1960s Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4tb298wq Author Tran, Andrina Publication Date 2011-05-31 Undergraduate eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California ““RRAADDIICCAALLSS FFOORR CCAAPPIITTAALLIISSMM”” Ayn Rand and Youth During the 1960s ANDRINA TRAN DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY There is a fundamental conviction which some people never acquire, some hold only in their youth, and a few hold to the end of their days – the conviction that ideas matter. In one’s youth that conviction is experienced as a self-evident absolute, and one is unable fully to believe that there are people who do not share it. That ideas matter means that knowledge matters, that truth matters, that one’s mind matters. And the radiance of that certainty, in the process of growing up, is the best aspect of youth. –Ayn Rand CONTENTS Acknowledgements 2 INTRODUCTION 2 I THE QUIETEST REVOLUTION IN HISTORY 11 II MARKETING OBJECTIVISM 24 III THE THRILL OF TREASON 32 IV LIFE, LIBERTY, PROPERTY: Persuasion and the Draft 38 V LIBERTARIANS RISING 46 EPILOGUE: MEMORY & HISTORY 52 Bibliography 55 Appendix 61 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Even a paper pertaining to egoism could not have come into existence without the generous support of so many others. I would like to thank the Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship Program, the Center for the Study of Representation at the Institute of Governmental Studies, and the Center for the Comparative Study of Right-Wing Movements for funding the various stages of my research. -

“The Experience of Flying”: the Rand Dogma and Its Literary Vehicle Camille Bond Submitted in the Partial Fulfillment Of

“The Experience of Flying”: The Rand Dogma and its Literary Vehicle Camille Bond Submitted in the Partial Fulfillment of the Prerequisite for Honors in English April 2017 © 2017 Camille Bond The greatest victory is that which requires no battle. Sun Tzu, The Art of War CONTENTS INTRODUCTION: 2 WHY STUDY RAND? CHAPTER ONE: 8 ON THE FOUNTAINHEAD AND CHARACTER CHAPTER TWO: 39 ON ATLAS SHRUGGED AND PLOT CONCLUSION 70 WORKS CITED 71 Bond 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To Bill Cain: Thank you for taking this project under your wing! I could not have asked for a more helpful advisor on what has turned out to be one of the most satisfying journeys of my life. To James Noggle and Jimmy Wallenstein: Thank you for your keen suggestions and advice, which brought new contexts and a clearer direction to this project. To Adam Weiner: Thank you for your assistance, and for the inspiration that How Bad Writing Destroyed the World provided. And to my family: Thank you for your support and encouragement, and for making this project possible. Bond 2 INTRODUCTION: WHY STUDY RAND? Very understandably, I have been asked the question “Why would you study Ayn Rand?” dozens of times since I undertook this project over the summer of 2016. In a decidedly liberal community, Rand’s name alone invokes hostility and disgust; even my past self would have been puzzled to learn that she would go on to spend a year of her life engaging academically with Rand’s work. Many of Rand’s ideas are morally repulsive; it can be physically difficult to read her fiction. -

Rand, Hayek, and the Ethics of the Micro- and Macro-Cosmos Steven Horwitz

Centenary Symposium, Part II Ayn Rand Among the Austrians Two Worlds at Once: Rand, Hayek, and the Ethics of the Micro- and Macro-cosmos Steven Horwitz Moreover, the structures of the extended order are made up not only of individuals but also of many, often overlapping, sub-orders within which old instinctual responses, such as solidarity and altruism, continue to retain some importance by assisting voluntary collaboration, even though they are incapable, by themselves, of creating a basis for the more extended order. Part of our present difficulty is that we must constantly adjust our lives, our thoughts and our emotions, in order to live simultaneously within different kinds of orders according to different rules. So we must learn to live in two sorts of worlds at once. — F. A. Hayek (1989, 18; emphasis added) Introduction A title that contains Rand, Hayek, and the ethics of anything might well raise a few eyebrows among the cognoscenti. After all, Ayn Rand was a champion of an objective ethics and railed against anyone who suggested that a meaningful ethics could be anything but objective in her sense. F. A. Hayek (1989, 10), by contrast, argued explicitly that “Ethics is the last fortress in which human pride must now bow in recognition of its origins. Such an evolutionary theory of morality is . neither instinctual nor a creation of reason.” Thus we are faced with two thinkers who have strongly opposed explanations for the source of ethical rules. However, despite those differences, both Rand and Hayek do wind up with some similar conclusions. For one, both argued that there was a strong link between ethics, political philosophy, and the role of the state. -

2020 Anthem Winning Essay 8Th, 9Th and 10Th Grade

2020 ANTHEM WINNING ESSAY 8TH, 9TH AND 10TH GRADE FIRST PLACE Georgia Mirică, Bucharest, Romania – American International School of Bucharest, Voluntari, Bucharest, Romania Aside from very rare exceptions, there is no opposition to the leaders in this society. Why is this? What ideas must the people in this society have accepted to live a life of obedience, drudgery and fear? The systematic construction of the literary universe in which Ayn Rand’s Anthem unfolds oversees a global society that strips human beings of their fundamental dignities and forces them to live in constant oppression and suppression of individualism. The novella follows the protagonist, Equality 7-2521, in his discovery of forbidden knowledge and subsequent escape, divulging truths about the dangers of collectivist ideals and totalitarianism, holding a mirror up to a tumultuous contemporary world. In Anthem, the re-programming of human values through complete indoctrination of collectivist ideals makes it so that the inhabitants of this society cease to be individual human beings, and instead are viewed as gears in a vast system. Having no notion of the self, they accept oppression as dutiful, being depersonalized to the point that they can be exploited completely without rebellion. Violently cradled by the arms of a totalitarian state from birth, perpetually kept in darkness, halted by ideological barriers, the result is a people submissive to abuse without question, having never been taught to question. One may argue that, upon birth, human beings are no more than lumps of clay to be shaped by this mysterious force called life and hardened by maturity, adopting the values of their environment unconsciously. -

Objectivism: Ayn Rand's Personal Philosophy

Objectivism: Ayn Rand’s Personal Philosophy These notes are taken from The Reader’s Guide to the Writings and Philosophy of Ayn Rand found at the end of Centennial Editions of Anthem. Ayn Rand provides a nutshell version of Objectivism by describing four aspects of it: Metaphysics the philosophy of what constitutes REALITY (How do we know what reality is?) Epistemology the philosophy of knowledge (How do we know what we know?) Ethics the philosophy of how we determine what is right vs. wrong, fair vs. unfair Politics the philosophy of how we govern groups of people Objectivism holds the following ideas: Metaphysics Objective Reality Epistemology Reason Ethics Self-Interest Politics Capitalism A further exploration of the ideas: Metaphysics Objective Reality Rand agrees with Naturalism in that reality is observable and measurable. There is one reality. She disagrees with Modernism in that Modernists believe in Subjective Reality, the idea that humans CREATE reality through their perceptions. Rand says that our only ability is to perceive reality, not create it. “facts are facts” This believe precludes (makes impossible) a belief in the supernatural. Epistemology Reason Rand agrees with the Enlightenment that we should use reason to achieve our goals. She holds that reason is man’s highest virtue. Other ways of “knowing what we know” is through faith, tradition, and intuition, none of which she would deem valid methods of “knowing.” Ethics Self-Interest Rand believes wholly in acting upon one’s self-interest. No one should sacrifice himself for others or sacrifice others for himself. This idea would preclude any altruistic acts. -

Who Studies Philosophy?

Who Studies Philosophy? Created with support from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundat ion Amer ican Philosophical lDAssociation Academia Sheila Bair, president of Washington College and former FDIC chair Noam Chomsky , professor , activist , author, and public intellectual Alice Domurat Dreger, professor , activist , and author Rev. John I. Jenkins, President, University of Notre Dame Aung San Suu Kyi Activism Stokely Carmichael Stokely Carmichael / Kwame lure, civil rights leader Angela Davis, social act ivist Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., civil rights leader Aung San Suu Kyi, 2002 Nobel Peace Prize winner Business Herbert Allison Jr., former Fannie Mae CEO Martin Luther King Jr. Stewart Butterfield, co-founder of Flickr Angela Davis Patrick Byrne, founder of Overstock.com Robert Greenhill, investment banker Reid Hoffman, co-founder of Linked In Damon Horowitz, entrepreneur and in-house philosopher at Google Carl Icahn, investor and former CEO of TWA Airlines Gerald Levin, former CEO of Time Warner, Inc. John Mackey, co-founder and co-CEO of Whole Foods Market Stewart Butterfield Sheila Bair Lachlan Murdoch, media magnate and son of Rupert Murdoch Max Palevsky, co-founder of Intel and venture capitalist Larry Sanger, co-founder of Wikipedia George Soros, investor and ph ilanthropist Peter Thiel, founder of PayPal News and Journalism Barbara Amiel, Lady Black of Cross harbour, journalist and writer Juan Williams Larry Sanger John Chancellor, journal ist Chris Hayes, journalist, political commentator, and MSNBC host Tamara Keith, journalist and NPR White House correspondent Kathryn Jean Lopez, journalist and political commentator Stone Phillips, broadcaster George F. Will, journalist , author , and political commentator Juan Williams, journalist Kathryn Jean Lopez Photos pub lic do main o r Creati ve Com mons. -

From the Instructor

From the Instructor Nicholas wrote this paper for my WR 150 course that surveys debates surrounding the free market. The second major paper in the course challenges students to contend with two uncompromising visions of the market’s virtues and evils: Karl Marx’s narrative of exploitation and estranged labor in The Communist Manifesto vs. John Galt’s forceful speech at the end of Atlas Shrugged, through which Ayn Rand asserts that competition alone can engender individual autonomy and national pros- perity. As a writer, the young Marx exemplifies many of the lessons that I teach my students. He provides an insightful and consistent framework for analysis—class relations—but does so through an elegant story with clear protagonists, antagonists, and a compelling narrative of historical struggle. Rand consciously inverts aspects of Marx’s narrative, contrasting “men of ability,” personified by Galt himself, with the weaker strata of society who seek shelter from the vicissitudes of struggle. Nicholas demonstrates in this paper his capacity to grasp the core points of contention between Rand and Marx, but also to elucidate the relevance of their grand visions for contemporary political debates in clear, insightful, and often clever prose. Nicholas frequently settled on a theme and argument from the first draft of his papers, and spent subsequent drafts developing those ideas further. He made good use of scholarly sources to substantiate his argument in this paper, especially when demon- strating that Rand, far from being a marginal twentieth-century thinker, has attained a mythical status for the contemporary American Right that is nearly on a par with the cult of Marxism in the scholarly and political movements of the past century. -

ART DECO and BRAZILIAN MODERNISM a Dissertation

SLEEK WORDS: ART DECO AND BRAZILIAN MODERNISM A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy in Spanish By Patricia A. Soler, M.S. Washington, DC January 23, 2014 Copyright by Patricia A. Soler All rights reserved ii SLEEK WORDS: ART DECO AND BRAZILIAN MODERNISM Patricia A. Soler, M.S. Thesis advisor: Gwen Kirkpatrick, Ph.D. ABSTRACT I explore Art Deco in the Brazilian Modernist movement during the 1920s. Art Deco is a decorative arts style that rose to global prominence during this decade and its proponents adopted and adapted the style in order to nationalize it; in the case of Brazil, the style became nationalized primarily by means of the application of indigenous motifs. The Brazilian Modernists created their own manifestations of the style, particularly in illustration and graphic design. I make this analysis by utilizing primary source materials to demonstrate the style’s prominence in Brazilian Modernism and by exploring the handcrafted and mechanical techniques used to produce the movement’s printed texts. I explore the origins of the Art Deco style and the decorative arts field and determine the sources for the style, specifically avant-garde, primitivist, and erotic sources, to demonstrate the style’s elasticity. Its elasticity allowed it to be nationalized on a global scale during the 1920s; by the 1930s, however, many fascist-leaning forces co- opted the style for their own projects. I examine the architectural field in the Brazil during the 1920s. -

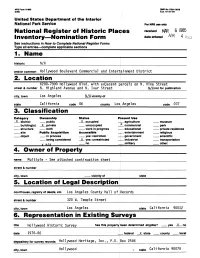

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form 1. Name 2. Location___4. Owner Off

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (342) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS UM only National Register of Historic Places received MAR 6 l985 Inventory—Nomination Form date entered APR 4 ibco See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections__________ 1. Name _________N/A_________________________ and/or common Hollywood Boulevard Commercial and Entertainment District 2. Location___________________________ 6200-7000 Hollywood Blvd. with adjacent parcels on N. Vine Street street & number N. Highland Avenue and N. Ivar Street -N/Anot for publication city, town Los Angeles vicinity of state California code 06 county Los Angeles code 037 3. Classification Category Ownership Status P resent Use * district public X occupied agriculture museum V ** building(s) x private Mnpccupied ^ commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible _ entertainment religious object in process yes: restricted = government scientific being considered X yes: unrestricted _ __ industrial transportation x n/a no __ military 4. Owner off Property name Multiple - See attached continuation sheet street & number city, town vicinity of state 5. Location off Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Los Angeles County Hall of Records street & number 320 W. Temple Street city,wuy, townluwii _______________~~~Los .Angeles... 3 ~ . ~~._____________________________ state California 90012 6. Representation -

Atlas Shrugged (Centennial Ed

ATLAS SHRUGGED (CENTENNIAL ED. PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Rand Ayn | 1192 pages | 01 May 2005 | Penguin Putnam Inc | 9780525948926 | English | New York, United States Atlas Shrugged (Centennial Ed. PDF Book They are all available in Signet editions, as is the magnificent statement of her artistic credo, The Romantic Manifesto. Richard McLaughlin, reviewing the novel for The American Mercury , described it as a "long overdue" polemic against the welfare state with an "exciting, suspenseful plot", although unnecessarily long. At the climax of the novel, the untalented but successful architect Peter Keating, a college friend of his, pleads with Roark for help in designing a prestigious project that Roark himself wanted but was too unpopular to win. These are two entirely different conceptions, with entirely— immensely and diametrically opposed —different consequences. Anthem In a world that places the good of society above all else, why is a man with a revolutionary invention that would benefit everyone forced to run for his life? What were your first impressions of her? The major novels of Ayn Rand contain superlative values that are unique in our age. Customers who bought this item also bought. On her way to Daniels, Dagny meets a hobo with a story that reveals the secret of the motor: it was invented and abandoned by an engineer named John Galt, who is the inspiration for the common saying. Written in , Anthem was first published in England; it was refused publication in America until , for reasons the reader can discover by reading it for himself. Retrieved September 21, Retrieved February 9, What happens to the world when the Prime Movers go on strike.