1 Language and Reality in Buddhism the Case for Moderate Linguistic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anattā and Nibbāna: Egolessness and Deliverance

Anattā and Nibbāna Egolessness and Deliverance by Nyanaponika Thera Buddhist Publication Society Kandy • Sri Lanka The Wheel Publication No. 11 First published: 1959 Reprinted: 1971, 1986 A slightly differing German version of this essay appeared in 1951 in the magazine Die Einsicht. The English version was first published in the quarterly The Light of the Dhamma, Vol. IV, No. 3 (Rangoon 1957) under the title “Nibbāna in the Light of the Middle Doctrine.” BPS Online Edition © (2008) Digital Transcription Source: BPS Transcription Project For free distribution. This work may be republished, reformatted, reprinted and redistributed in any medium. However, any such republication and redistribution is to be made available to the public on a free and unrestricted basis and translations and other derivative works are to be clearly marked as such. Contents Introduction 2 I. The Nihilistic-Negative Extreme 5 II The Positive-Metaphysical Extreme 9 III Transcending the Extremes 14 Introduction This world, Kaccāna, usually leans upon a duality: upon (the belief in) existence or non- existence.… Avoiding these two extremes, the Perfect One shows the doctrine in the middle: Dependent on ignorance are the kamma-formations.… By the cessation of ignorance, kamma-formations cease.… (SN 12:15) The above saying of the Buddha speaks of the duality of existence (atthitā) and non-existence (natthitā). These two terms refer to the theories of eternalism (sassata-diṭṭhi) and annihilationism (uccheda-diṭṭhi), the basic misconceptions of actuality that in various forms repeatedly reappear in the history of human thought. Eternalism is the belief in a permanent substance or entity, whether conceived as a multitude of individual souls or selves, created or not, as a monistic world-soul, a deity of any description, or a combination of any of these notions. -

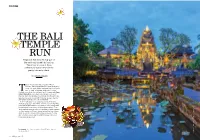

THE BALI TEMPLE RUN Temples in Bali Share the Top Spot on the Must-Visit List with Its Beaches

CULTURE THE BALI TEMPLE RUN Temples in Bali share the top spot on the must-visit list with its beaches. Take a look at some of these architectural marvels that dot the pretty Indonesian island. TEXT ANURAG MALLICK he sun was about to set across the cliffs of Uluwatu, the stony headland that gave the place its name. Our guide, Made, explained that ulu is ‘land’s end’ or ‘head’ in Balinese, while watu is ‘stone’. PerchedT on a rock at the southwest tip of the peninsula, Pura Luhur Uluwatu is a pura segara (sea temple) and one of the nine directional temples of Bali protecting the island. We gaped at the waves crashing 230 ft below, unaware that the real spectacle was about to unfold elsewhere. A short walk led us to an amphitheatre overlooking the dramatic seascape. In the middle, around a sacred lamp, fifty bare-chested performers sat in concentric rings, unperturbed by the hushed conversations of the packed audience. They sat in meditative repose, with cool sandalwood paste smeared on their temples and flowers tucked behind their ears. Sharp at six, chants of cak ke-cak stirred the evening air. For the next one hour, we sat open-mouthed in awe at Bali’s most fascinating temple ritual. Facing page: Pura Taman Saraswati is a beautiful water temple in the heart of Ubud. Elena Ermakova / Shutterstock.com; All illustrations: Shutterstock.com All illustrations: / Shutterstock.com; Elena Ermakova 102 JetWings April 2017 JetWings April 2017 103 CULTURE The Kecak dance, filmed in movies such as There are four main types of temples in Bali – public Samsara and Tarsem Singh’s The Fall, was an temples, village temples, family temples for ancestor worship, animated retelling of the popular Hindu epic and functional temples based on profession. -

The Fundamentals of Meditation Practice

TheThe FundamentalsFundamentals ofof MeditationMeditation PracticePractice by Ting Chen Translated by Dharma Master Lok To HAN DD ET U 'S B B O RY eOK LIBRA E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.buddhanet.net Buddha Dharma Education Association Inc. The Fundamentals of Meditation Practice by Ting Chen Translated by Dharma Master Lok To Edited by Sam Landberg & Dr. Frank G. French 2 Transfer-of-Merit Vow (Parinamana) For All Donors May all the merit and grace gained from adorning Buddha’s Pure Land, from loving our parents, from serving our country and from respecting all sen- tient beings be transformed and transferred for the benefit and salvation of all suffering sentient be- ings on the three evil paths. Furthermore, may we who read and hear this Buddhadharma and, there- after, generate our Bodhi Minds be reborn, at the end of our lives, in the Pure Land. Sutra Translation Committee of the United States and Canada, 1999 — website: http://www.ymba.org/freebooks_main.html Acknowledgments We respectfully acknowledge the assistance, support and cooperation of the following advisors, without whom this book could not have been produced: Dayi Shi; Chuanbai Shi; Dr. John Chen; Amado Li; Cherry Li; Hoi-Sang Yu; Tsai Ping Chiang; Vera Man; Way Zen; Jack Lin; Tony Aromando; and Ling Wang. They are all to be thanked for editing and clarifying the text, sharpening the translation and preparing the manuscript for publication. Their devotion to and concentration on the completion of this project, on a voluntary basis, are highly appreciated. 3 Contents • Translator’s Introduction...................... 5 • The Foundation of Meditation Practice. -

The Oral Transmission of the Early Buddhist Literature

JIABS Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies Volume 27 Number 1 2004 David SEYFORT RUEGG Aspects of the Investigation of the (earlier) Indian Mahayana....... 3 Giulio AGOSTINI Buddhist Sources on Feticide as Distinct from Homicide ............... 63 Alexander WYNNE The Oral Transmission of the Early Buddhist Literature ................ 97 Robert MAYER Pelliot tibétain 349: A Dunhuang Tibetan Text on rDo rje Phur pa 129 Sam VAN SCHAIK The Early Days of the Great Perfection........................................... 165 Charles MÜLLER The Yogacara Two Hindrances and their Reinterpretations in East Asia.................................................................................................... 207 Book Review Kurt A. BEHRENDT, The Buddhist Architecture of Gandhara. Handbuch der Orientalistik, section II, India, volume seventeen, Brill, Leiden-Boston, 2004 by Gérard FUSSMAN............................................................................. 237 Notes on the Contributors............................................................................ 251 THE ORAL TRANSMISSION OF EARLY BUDDHIST LITERATURE1 ALEXANDER WYNNE Two theories have been proposed to explain the oral transmission of early Buddhist literature. Some scholars have argued that the early literature was not rigidly fixed because it was improvised in recitation, whereas others have claimed that word for word accuracy was required when it was recited. This paper examines these different theories and shows that the internal evi- dence of the Pali canon supports the theory of a relatively fixed oral trans- mission of the early Buddhist literature. 1. Introduction Our knowledge of early Buddhism depends entirely upon the canoni- cal texts which claim to go back to the Buddha’s life and soon afterwards. But these texts, contained primarily in the Sutra and Vinaya collections of the various sects, are of questionable historical worth, for their most basic claim cannot be entirely true — all of these texts, or even most of them, cannot go back to the Buddha’s life. -

Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism, Revised Edition

REVISED EDITION John Powers ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 1 Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 2 ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 3 Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism revised edition by John Powers Snow Lion Publications ithaca, new york • boulder, colorado ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 4 Snow Lion Publications P.O. Box 6483 • Ithaca, NY 14851 USA (607) 273-8519 • www.snowlionpub.com © 1995, 2007 by John Powers All rights reserved. First edition 1995 Second edition 2007 No portion of this book may be reproduced by any means without prior written permission from the publisher. Printed in Canada on acid-free recycled paper. Designed and typeset by Gopa & Ted2, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Powers, John, 1957- Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism / by John Powers. — Rev. ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN-13: 978-1-55939-282-2 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-55939-282-7 (alk. paper) 1. Buddhism—China—Tibet. 2. Tibet (China)—Religion. I. Title. BQ7604.P69 2007 294.3’923—dc22 2007019309 ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 5 Table of Contents Preface 11 Technical Note 17 Introduction 21 Part One: The Indian Background 1. Buddhism in India 31 The Buddha 31 The Buddha’s Life and Lives 34 Epilogue 56 2. Some Important Buddhist Doctrines 63 Cyclic Existence 63 Appearance and Reality 71 3. Meditation 81 The Role of Meditation in Indian and Tibetan Buddhism 81 Stabilizing and Analytical Meditation 85 The Five Buddhist Paths 91 4. -

The Tulku System in Tibetan Buddhism: Its Reliability, Orthodoxy and Social Impacts

The Tulku System in Tibetan Buddhism: Its Reliability, Orthodoxy and Social Impacts By Ramin Etesami A thesis submitted to the graduate school in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the International Buddhist College, Thailand March, 20 Abstract The Tulku institution is a unique characteristic of Tibetan Buddhism with a central role in this tradition, to the extent that it is present in almost every aspect of Tibet’s culture and tradition. However, despite this central role and the scope and diversity of the socio-religious aspects of the institution, only a few studies have so far been conducted to shed light on it. On the other hand, an aura of sacredness; distorted pictures projected by the media and film industries;political propaganda and misinformation; and tendencies to follow a pattern of cult behavior; have made the Tulku institution a highly controversial topic for research; and consequently, an objective study of the institution based on a critical approach is difficult. The current research is an attempt to comprehensively examine different dimensions of the Tulku tradition with an emphasis on the issue of its orthodoxy with respect to the core doctrines of Buddhism and the social implications of the practice. In this research, extreme caution has been practiced to firstly, avoid any kind of bias rooted in faith and belief; and secondly, to follow a scientific methodology in reviewing evidence and scriptures related to the research topic. Through a comprehensive study of historical accounts, core Buddhist texts and hagiographic literature, this study has found that while the basic Buddhist doctrines allow the possibility for a Buddhist teacher or an advanced practitioner to “return back to accomplish his tasks, the lack of any historical precedence which can be viewed as a typical example of the practice in early Buddhism makes the issue of its orthodoxy equivocal and relative. -

Buddhism As a Pragmatic Religious Tradition

CHAPTER 1 Introduction: Buddhism as a Pragmatic Religious Tradition Our approach to Religion can be called “vernacular” . [It is] concerned with the kinds of data that may, even- tually, be able to give us some substantial insight into how religions have played their part in history, affect- ing people’s ability to respond to environmental crises; to earthquakes, floods, famines, pandemics; as well as to social ills and civil wars. Besides these evils, there are the everyday difficulties and personal disasters we all face from time to time. Religions have played their part in keeping people sane and stable....We thus see religions as an integral part of vernacular history, as a strand woven into lives of individuals, families, social groups, and whole societies. Religions are like technol- ogy in that respect: ever present and influential to peo- ple’s ability to solve life’s problems day by day. Vernon Reynolds and Ralph Tanner, The Social Ecology of Religion The Buddhist faith expresses itself most authentically in the processions of statues through towns, the noc- turnal illuminations in the streets and countryside. It is on such occasions that communion between the reli- gious and laity takes place . without which the religion could be no more than an exercise of recluse monks. Jacques Gernet, Buddhism in Chinese Society: An Economic History from the Fifth to the Tenth Centuries 1 2 Popular Buddhist Texts from Nepal Whosoever maintains that it is karma that injures beings, and besides it there is no other reason for pain, his proposition is false.... Milindapañha IV.I.62 Health, good luck, peace, and progeny have been the near- universal wishes of humanity. -

Meningkatkan Mutu Umat Melalui Pemahaman Yang Benar Terhadap Simbol Acintya (Perspektif Siwa Siddhanta)

MENINGKATKAN MUTU UMAT MELALUI PEMAHAMAN YANG BENAR TERHADAP SIMBOL ACINTYA (PERSPEKTIF SIWA SIDDHANTA) Oleh: I Gusti Made Widya Sena Dosen Fakultas Brahma Widya IHDN Denpasar Abstract God will be very difficult if understood with eye, to the knowledge of God through nature, private and personification through the use of various symbols God can help humans understand God's infinite towards the unification of these two elements, namely the unification of physical and spiritual. Acintya as a symbol or a manifestation of God 's Omnipotence itself . That what really " can not imagine it turns out " could imagine " through media portrayals , relief or statue. All these symbols are manifested Acintya it by taking the form of the dance of Shiva Nataraja, namely as a depiction of God's omnipotence , to bring in the actual symbol " unthinkable " that have a meaning that people are in a situation where emotions religinya very close with God. Keywords: Theology, Acintya, Siwa Siddhanta & Siwa Nataraja I. PENDAHULUAN Kehidupan sebagai manusia merupakan hidup yang paling sempurna dibandingkan dengan makhluk ciptaan Tuhan lainnya, hal ini dikarenakan selain memiliki tubuh jasmani, manusia juga memiliki unsur rohani. Kedua unsur ini tidak dapat dipisahkan dan saling melengkapi diantara satu dengan lainnya. Layaknya garam di lautan, tidak dapat dilihat secara langsung tapi terasa asin ketika dikecap. Jasmani manusia difungsikan ketika melakukan berbagai macam aktivitas di dunia, baik dalam memenuhi kebutuhan hidup (kebutuhan pangan, sandang dan papan), reproduksi, bersosialisasi dengan makhluk lainnya, dan berbagai aktivitas lainnya, sedangkan tubuh rohani difungsikan dalam merasakan, memahami dan membangun hubungan dengan Sang Pencipta, sehingga ketenangan, keindahan dan kebijaksanaan lahir ketika penyatuan diantara kedua unsur ini berjalan selaras, serasi dan seimbang. -

Buddhist-Christian Dialogue As Theological Exchange an Orthodox Contribution to Comparative Eology

199 West 8th Avenue, Suite 3, Eugene, OR 97401 PICKWICK Publications Tel. (541) 344-1528 • Fax (541) 344-1506 An imprint of WIPF and STOCK Publishers Visit our Web site at www.wipfandstock.com Buddhist-Christian Dialogue as Theological Exchange An Orthodox Contribution to Comparative eology Ernest M. Valea is book is intended to encourage the use of comparative theology in contemporary Buddhist-Christian dialogue as a new approach that would truly respect each religious tradition’s uniqueness and make dialogue beneficial for all participants interested in a real theological exchange. As a result of the impasse reached by the current theologies of religions (exclusivism, inclusivism, and pluralism) in formulating a constructive approach in dialogue, this volume assesses the thought of the founding fathers of an academic Buddhist-Christian dialogue in search of clues that would encourage a comparativist approach. ese founding fathers are considered to be three important representatives of the Kyoto School—Kitaro Nishida, Keiji Nishitani, and Masao Abe—and John Cobb, an American process theologian. e guiding line for assessing their views of dialogue is the concept of human perfection, as it is expressed by the original traditions in Mahayana Buddhism and Orthodox Christianity. Following Abe’s methodology in dialogue, an Orthodox contribu- tion to comparative theology proposes a reciprocal enrichment of traditions, not by syncretistic means, but by providing a better understanding and even correction of one’s own tradition when considering it in the light of the other, while using internal resources for making the necessary corrections. ISBN: 978-1-4982-2119-1 | 262 pp. -

What the Upanisads Teach

What the Upanisads Teach by Suhotra Swami Part One The Muktikopanisad lists the names of 108 Upanisads (see Cd Adi 7. 108p). Of these, Srila Prabhupada states that 11 are considered to be the topmost: Isa, Kena, Katha, Prasna, Mundaka, Mandukya, Taittiriya, Aitareya, Chandogya, Brhadaranyaka and Svetasvatara . For the first 10 of these 11, Sankaracarya and Madhvacarya wrote commentaries. Besides these commentaries, in their bhasyas on Vedanta-sutra they have cited passages from Svetasvatara Upanisad , as well as Subala, Kausitaki and Mahanarayana Upanisads. Ramanujacarya commented on the important passages of 9 of the first 10 Upanisads. Because the first 10 received special attention from the 3 great bhasyakaras , they are called Dasopanisad . Along with the 11 listed as topmost by Srila Prabhupada, 3 which Sankara and Madhva quoted in their sutra-bhasyas -- Subala, Kausitaki and Mahanarayana Upanisads --are considered more important than the remaining 97 Upanisads. That is because these 14 Upanisads are directly referred to by Srila Vyasadeva himself in Vedanta-sutra . Thus the 14 Upanisads of Vedanta are: Isa, Kena, Katha, Prasna, Mundaka, Mandukya, Aitareya, Taittiriya, Brhadaranyaka, Chandogya, Svetasvatara, Kausitaki, Subala and Mahanarayana. These 14 belong to various portions of the 4 Vedas-- Rg, Yajus, Sama and Atharva. Of the 14, 8 ( Brhadaranyaka, Chandogya, Taittrirya, Mundaka, Katha, Aitareya, Prasna and Svetasvatara ) are employed by Vyasa in sutras that are considered especially important. In the Gaudiya Vaisnava sampradaya , Srila Baladeva Vidyabhusana shines as an acarya of vedanta-darsana. Other great Gaudiya acaryas were not met with the need to demonstrate the link between Mahaprabhu's siksa and the Upanisads and Vedanta-sutra. -

A Buddhist Inspiration for a Contemporary Psychotherapy

1 A BUDDHIST INSPIRATION FOR A CONTEMPORARY PSYCHOTHERAPY Gay Watson Thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the School of Oriental & African Studies, University of London. 1996 ProQuest Number: 10731695 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731695 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT It is almost exactly one hundred years since the popular and not merely academic dissemination of Buddhism in the West began. During this time a dialogue has grown up between Buddhism and the Western discipline of psychotherapy. It is the contention of this work that Buddhist philosophy and praxis have much to offer a contemporary psychotherapy. Firstly, in general, for its long history of the experiential exploration of mind and for the practices of cultivation based thereon, and secondly, more specifically, for the relevance and resonance of specific Buddhist doctrines to contemporary problematics. Thus, this work attempts, on the basis of a three-way conversation between Buddhism, psychotherapy and various themes from contemporary discourse, to suggest a psychotherapy that may be helpful and relevant to the current horizons of thought and contemporary psychopathologies which are substantially different from those prevalent at the time of psychotherapy's early years. -

Contesting Buddhist Narratives Democratization, Nationalism, and Communal Violence in Myanmar

Policy Studies 71 Contesting Buddhist Narratives Democratization, Nationalism, and Communal Violence in Myanmar Matthew J. Walton and Susan Hayward Contesting Buddhist Narratives Democratization, Nationalism, and Communal Violence in Myanmar About the East-West Center The East-West Center promotes better relations and understanding among the people and nations of the United States, Asia, and the Pacific through cooperative study, research, and dialogue. Established by the US Congress in 1960, the Center serves as a resource for infor- mation and analysis on critical issues of common concern, bringing people together to exchange views, build expertise, and develop policy options. The Center’s 21-acre Honolulu campus, adjacent to the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, is located midway between Asia and the US main- land and features research, residential, and international conference facilities. The Center’s Washington, DC, office focuses on preparing the United States for an era of growing Asia Pacific prominence. The Center is an independent, public, nonprofit organization with funding from the US government, and additional support provided by private agencies, individuals, foundations, corporations, and govern- ments in the region. Policy Studies an East-West Center series Series Editors Dieter Ernst and Marcus Mietzner Description Policy Studies presents original research on pressing economic and political policy challenges for governments and industry across Asia, About the East-West Center and for the region's relations with the United States. Written for the The East-West Center promotes better relations and understanding policy and business communities, academics, journalists, and the in- among the people and nations of the United States, Asia, and the formed public, the peer-reviewed publications in this series provide Pacifi c through cooperative study, research, and dialogue.