The Fantastic in Short Stories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fantasy and Imagination: Discovering the Threshold of Meaning David Michael Westlake

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library 5-2005 Fantasy and Imagination: Discovering the Threshold of Meaning David Michael Westlake Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Modern Literature Commons Recommended Citation Westlake, David Michael, "Fantasy and Imagination: Discovering the Threshold of Meaning" (2005). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 477. http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/477 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. FANTASY AND IMAGINATION: DISCOVERING THE THRESHOLD OF MEANING BY David Michael Westlake B.A. University of Maine, 1997 A MASTER PROJECT Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (in Liberal Studies) The Graduate School The University of Maine May, 2005 Advisory Committee: Kristina Passman, Associate Professor of Classical Language and Literature, Advisor Jay Bregrnan, Professor of History Nancy Ogle, Professor of Music FANTASY AND IMAGINATION: DISCOVERING THE THRESHOLD OF MEANING By David Michael Westlake Thesis Advisor: Dr. Kristina Passman An Abstract of the Master Project Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (in Liberal Studies) May, 2005 This thesis addresses the ultimate question of western humanity; how does one find meaning in the present era? It offers the reader one powerful way for this to happen, and that is through the stories found in the pages of Fantasy literature. It begins with Frederick Nietzsche's declaration that, "God is dead." This describes the situation of men and women in his time and today. -

The World of Fantasy Literature Has Little to Do with the Exotic Worlds It Describes

The world of fantasy literature has little to do with the exotic worlds it describes. It is generally tied to often well-earned connotations of cheap writing, childish escapism, overused tropes copied and pasted straight out of The Lord of the Rings, and a strong commercial vitality. Perhaps it is the comforting predictability that draws me in—but the same could be said of the delight that I feel when some clever author has taken the old and worn hero-cycle and turned it inside out. Maybe I just like dragons and swords. It could be that the neatly packaged, solvable problems within a work of fantasy literature, problems that are nothing like the ones I have to deal with, such as marauding demons or kidnappings by evil witches, are more attractive than my own more confusing ones. Somehow they remain inspiring and terrifying despite that. Since I was a child, fantasy has always been able to captivate me. I never spared much time for the bland narratives of a boy and his dog or the badly thought-out antics of neighborhood friends. I preferred the more dangerous realms of Redwall, populated by talking animals, or Artemis Fowl, a fairy-abducting, preteen, criminal mastermind. In fact, reading was so strongly ingrained in me that teachers, parents and friends had to, and on occasion still need to, ask me to put down my book. I really like reading, and at some point that love spilled over and I started to like writing, too. Telling a story does not have to be deep or meaningful in its lessons. -

MARCH 1St 2018

March 1st We love you, Archivist! MARCH 1st 2018 Attention PDF authors and publishers: Da Archive runs on your tolerance. If you want your product removed from this list, just tell us and it will not be included. This is a compilation of pdf share threads since 2015 and the rpg generals threads. Some things are from even earlier, like Lotsastuff’s collection. Thanks Lotsastuff, your pdf was inspirational. And all the Awesome Pioneer Dudes who built the foundations. Many of their names are still in the Big Collections A THOUSAND THANK YOUS to the Anon Brigade, who do all the digging, loading, and posting. Especially those elite commandos, the Nametag Legionaires, who selflessly achieve the improbable. - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - – - - - - - – The New Big Dog on the Block is Da Curated Archive. It probably has what you are looking for, so you might want to look there first. - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - – - - - - - – Don't think of this as a library index, think of it as Portobello Road in London, filled with bookstores and little street market booths and you have to talk to each shopkeeper. It has been cleaned up some, labeled poorly, and shuffled about a little to perhaps be more useful. There are links to ~16,000 pdfs. Don't be intimidated, some are duplicates. Go get a coffee and browse. Some links are encoded without a hyperlink to restrict spiderbot activity. You will have to complete the link. Sorry for the inconvenience. Others are encoded but have a working hyperlink underneath. Some are Spoonerisms or even written backwards, Enjoy! ss, @SS or $$ is Send Spaace, m3g@ is Megaa, <d0t> is a period or dot as in dot com, etc. -

Discovering by Analysis: Harry Potter and Youth Fantasy

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 459 865 IR 058 417 AUTHOR Center, Emily R. TITLE Discovering by Analysis: Harry Potter and Youth Fantasy. PUB DATE 2001-08-00 NOTE 38p.; Master of Library and Information Science Research Paper, Kent State University. PUB TYPE Dissertations/Theses (040) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescent Literature; *Childrens Literature; *Fantasy; Fiction; Literary Criticism; *Reading Material Selection; Tables (Data) IDENTIFIERS *Harry Potter; *Reading Lists ABSTRACT There has been a recent surge in the popularity of youth fantasy books; this can be partially attributed to the popularity of J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter series. Librarians and others who recommend books to youth are having a difficult time suggesting other fantasy books to those who have read the Harry Potter series and want to read other similar fantasy books, because they are not as familiar with the youth fantasy genre as with other genres. This study analyzed a list of youth fantasy books and compared them to the books in the Harry Potter series, through a breakdown of their fantasy elements (i.e., fantasy subgenres, main characters, secondary characters, plot elements, and miscellaneous elements) .Books chosen for the study were selected from lists of youth fantasy books recommended to fantasy readers and others that are currently in print. The study provides a resource for fantasy readers by quantifying the elements of the youth fantasy books, as well as creating a guide for those interested in the Harry Potter books. It also helps fill a gap in the research of youth fantasy. Appendices include a youth fantasy reading list, the coding sheet, data tables, and final annotated book list.(Contains 10 references and 9 tables.)(Author/MES) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

Writing Fantasy #2—World Building

Writing Fantasy #2—World Building World building is at the core of writing fantasy. Your fantasy world shapes and defines every other aspect of your book: the characters, their strengths and limitations, and especially the plot. You make the rules, but that also means that you have to stick to them. That being said, world building is one of most fun parts of writing a fantasy novel. The ability to literally create a world, define the rules for a system of magic, build and populate cities, and then select and bring to life the people who will tell your story—your characters. In some books, the world is a character in itself. I created a world for my Raine Benares adventures that was familiar, yet at the same time new and exotic. I felt that having the action of my story happen in a place readers could recognize would enable them to not only instantly visualize the setting, but put themselves into the story itself. Being a bit of a Renaissance history buff, I based my city of Mermeia on Venice. The architecture conveys the Renaissance feel that I was going for, and it has canals instead of streets, giving my characters a means of transportation and a way to dump a body or two. I mean, how cool is that? And since the real Venice consists of many islands, my imaginary Mermeia does, too. However, I also used islands as a way to separate the not-quite-friendly-with-each-other races and groups of people that populate my books. -

Fantasy Magazine Issue 54, September 2011

Fantasy Magazine Issue 54, September 2011 Table of Contents Editorial by John Joseph Adams “Lessons From a Clockwork Queen” by Megan Arkenberg (fiction) Author Spotlight: Megan Arkenberg by T. J. McIntyre “Steampunk and the Architecture of Idealism” by David Brothers (nonfiction) “Using It and Losing It” by Jonathan Lethem (fiction) Author Spotlight: Jonathan Lethem by Wendy N. Wagner “The Language of Fantasy” by David Salo (nonfiction) “The Nymph’s Child” by Carrie Vaughn (fiction) Author Spotlight: Carrie Vaughn by Jennifer Konieczny “Ten Reasons to be a Pirate” by John “Ol’ Chumbucket” Baur & Mark “Cap’n Slappy” Summers (nonfiction) “Three Damnations: A Fugue” by James Alan Gardner (fiction) Author Spotlight: James Alan Gardner by T. J. McIntyre Feature Interview: Brandon Sanderson by Leigh Butler (nonfiction) Coming Attractions © 2011, Fantasy Magazine Cover Art by Jennifer Mei. Ebook design by Neil Clarke www.fantasy-magazine.com Editorial, September 2011 John Joseph Adams Welcome to issue fifty-four of Fantasy Magazine! The big news at Fantasy HQ this month is that your humble editor has been nominated for two World Fantasy Awards! My anthology The Way of the Wizard is a finalist for best anthology, and I personally am nominated in the “special award (professional)” category. So, congratulations, to . well, me, I guess! And of course to all of the contributors to The Way of the Wizard, and everyone who I’ve worked with over the past year that made both nominations possible. With that out of the way, here’s what we’ve got on tap this month: Even when things are working just like clockwork, sometimes there is still room for error—and even love. -

Defining Fantasy

1 DEFINING FANTASY by Steven S. Long This article is my take on what makes a story Fantasy, the major elements that tend to appear in Fantasy, and perhaps most importantly what the different subgenres of Fantasy are (and what distinguishes them). I’ve adapted it from Chapter One of my book Fantasy Hero, available from Hero Games at www.herogames.com, by eliminating or changing most (but not all) references to gaming and gamers. My insights on Fantasy may not be new or revelatory, but hopefully they at least establish a common ground for discussion. I often find that when people talk about Fantasy they run into trouble right away because they don’t define their terms. A person will use the term “Swords and Sorcery” or “Epic Fantasy” without explaining what he means by that. Since other people may interpret those terms differently, this leads to confusion on the part of the reader, misunderstandings, and all sorts of other frustrating nonsense. So I’m going to define my terms right off the bat. When I say a story is a Swords and Sorcery story, you can be sure that it falls within the general definitions and tropes discussed below. The same goes for Epic Fantasy or any other type of Fantasy tale. Please note that my goal here isn’t necessarily to persuade anyone to agree with me — I hope you will, but that’s not the point. What I call “Epic Fantasy” you may refer to as “Heroic Fantasy” or “Quest Fantasy” or “High Fantasy.” I don’t really care. -

Questing Feminism: Narrative Tensions and Magical Women in Modern Fantasy

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Open Access Dissertations 2018 Questing Feminism: Narrative Tensions and Magical Women in Modern Fantasy Kimberly Wickham University of Rhode Island, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss Recommended Citation Wickham, Kimberly, "Questing Feminism: Narrative Tensions and Magical Women in Modern Fantasy" (2018). Open Access Dissertations. Paper 716. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss/716 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. QUESTING FEMINISM: NARRATIVE TENSIONS AND MAGICAL WOMEN IN MODERN FANTASY BY KIMBERLY WICKHAM A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISH UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2018 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DISSERTATION OF KIMBERLY WICKHAM APPROVED: Dissertation Committee: Major Professor Naomi Mandel Carolyn Betensky Robert Widell Nasser H. Zawia DEAN OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2018 Abstract Works of Epic Fantasy often have the reputation of being formulaic, conservative works that simply replicate the same tired story lines and characters over and over. This assumption prevents Epic Fantasy works from achieving wide critical acceptance resulting in an under-analyzed and under-appreciated genre of literature. While some early works do follow the same narrative path as J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, Epic Fantasy has long challenged and reworked these narratives and character tropes. That many works of Epic Fantasy choose replicate the patriarchal structures found in our world is disappointing, but it is not an inherent feature of the genre. -

Seven Seas Will Release Re:Monster As Single PRICE: $12.99 / $15.99 CAN

S E V E N S E A S Kanekiru Kogitsune Re:Monster Vol. 4 A young man begins life anew as a lowly goblin in this action-packed shonen fantasy manga! Tomokui Kanata has suffered an early death, but his adventures are far from over. He is reborn into a fantastical world of monsters and magic--but as a lowly goblin! Not about to let that stop him, the now renamed Rou uses his new physical prowess and his old memories to plow ahead in a world where consuming other creatures allows him to acquire their powers. KEY SELLING POINTS: * POPULAR MANGA SUBJECT: Powerful shonen-style artwork and ON-SALE DATE: 8/27/2019 fast-paced action scenes will appeal to fans of such fantasy series as Overlord ISBN-13: 9781626927100 and Sword Art Online. * SPECIAL FEATURES: Seven Seas will release Re:Monster as single PRICE: $12.99 / $15.99 CAN. volumes with at least two full-color illustrations in each book. PAGES: 180 * BASED ON LIGHT NOVEL: The official manga adaptation of the popular SPINE: 181MM H | 5IN W IN Re:Monster light novel. CTN COUNT: 42 * SERIES INFORMATION: Total number of volumes are currently unknown SETTING: FANTASY WORLD but will have a planned pub whenever new volumes are available in Japan. AUTHOR HOME: KANEKIRU KOGITSUNE - JAPAN; KOBAYAKAWA HARUYOSHI - JAPAN 2 S E V E N S E A S Strike Tanaka Servamp Vol. 12 The unique vampire action-drama continues! When a stray black cat named Kuro crosses Mahiru Shirota's path, the high school freshman's life will never be the same again. -

Epics, Myth, and Modern Magic: Where Classics and Fantasy Collide

Student Research and Creative Works Book Collecting Contest Essays University of Puget Sound Year 2015 Epics, Myth, and Modern Magic: Where Classics and Fantasy Collide Alicia Matz University of Puget Sound, [email protected] This paper is posted at Sound Ideas. http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/book collecting essays/8 Alicia Matz Book Collecting Contest 2015 Epics, Myth, and Modern Magic: Where Classics and Fantasy Collide I really love books. So much so, that I happen to have a personal library of over 200 of them. The majority of this rather large collection is split two ways: modern fantasy novels and books on or from the classical antiquity. I started my fantasy collection at a very young age, with the books that formed my childhood: Harry Potter . While I had always been an avid reader, these books threw me into a frenzy. I just had to get my hands on fantasy books. I kept growing and growing my collection until my senior year in high school, when, as an AP Latin student, I read Vergil’s Aeneid in Latin. Although I had always had a love for ancient Greece and Rome, reading this work changed my life, and I decided to become a Classics major. Now when I go to the bookstore, the first place I browse is the fantasy section, and then I quickly move to the history section. Because of this, I have a lot of books on both of these topics. Ever since my freshman year I have wanted to submit a collection to the book collecting contest, but being the book aficionado that I am, I struggled to narrow down a theme. -

Fantasy and Reality: J.R.R

Volume 22 Number 3 Article 2 10-15-1999 Fantasy and Reality: J.R.R. Tolkien's World and the Fairy-Story Essay Verlyn Flieger University of Maryland, College Park Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Flieger, Verlyn (1999) "Fantasy and Reality: J.R.R. Tolkien's World and the Fairy-Story Essay," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 22 : No. 3 , Article 2. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol22/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Examines how Tolkien applied a central concept of “On Fairy-stories,” the idea that fantasy must be firmly based in reality, to his writing of The Lord of the Rings. -

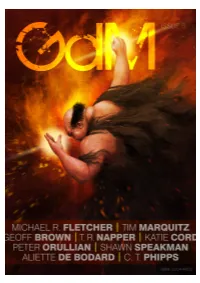

Grimdark-Magazine-Issue-6-PDF.Pdf

Contents From the Editor By Adrian Collins A Fair Man From The Vault of Heaven By Peter Orullian The Grimdark Villain Article by C.T. Phipps Review: Son of the Black Sword Author: Larry Correia Review by malrubius Excerpt: Blood of Innocents By Mitchell Hogan Publisher Roundtable Shawn Speakman, Katie Cord, Tim Marquitz, and Geoff Brown. Twelve Minutes to Vinh Quang By T.R. Napper Review: Dishonoured By CT Phipps An Interview with Aliette de Bodard At the Walls of Sinnlos A Manifest Delusions developmental short story by Michael R. Fletcher 2 The cover art for Grimdark Magazine issue #6 was created by Jason Deem. Jason Deem is an artist and designer residing in Dallas, Texas. More of his work can be found at: spiralhorizon.deviantart.com, on Twitter (@jason_deem) and on Instagram (spiralhorizonart). 3 From the Editor ADRIAN COLLINS On the 6th of November, 2015, our friend, colleague, and fellow grimdark enthusiast Kennet Rowan Gencks passed away unexpectedly. This one is for you, mate. Adrian Collins Founder Connect with the Grimdark Magazine team at: facebook.com/grimdarkmagazine twitter.com/AdrianGdMag grimdarkmagazine.com plus.google.com/+AdrianCollinsGdM/ pinterest.com/AdrianGdM/ 4 A Fair Man A story from The Vault of Heaven PETER ORULLIAN Pit Row reeked of sweat. And fear. Heavy sun fell across the necks of those who waited their turn in the pit. Some sat in silence, weapons like afterthoughts in their laps. Others trembled and chattered to anyone who’d spare a moment to listen. Fallow dust lazed around them all. The smell of old earth newly turned.