Wagner, Nietzsche, and the Idea of Bayreuth in Relation to Organization and Management Theory Josef Chytry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parsifal and Canada: a Documentary Study

Parsifal and Canada: A Documentary Study The Canadian Opera Company is preparing to stage Parsifal in Toronto for the first time in 115 years; seven performances are planned for the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts from September 25 to October 18, 2020. Restrictions on public gatherings imposed as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic have placed the production in jeopardy. Wagnerians have so far suffered the cancellation of the COC’s Flying Dutchman, Chicago Lyric Opera’s Ring cycle and the entire Bayreuth Festival for 2020. It will be a hard blow if the COC Parsifal follows in the footsteps of a projected performance of Parsifal in Montreal over 100 years ago. Quinlan Opera Company from England, which mounted a series of 20 operas in Montreal in the spring of 1914 (including a complete Ring cycle), announced plans to return in the fall of 1914 for another feast of opera, including Parsifal. But World War One intervened, the Parsifal production was cancelled, and the Quinlan company went out of business. Let us hope that history does not repeat itself.1 While we await news of whether the COC production will be mounted, it is an opportune time to reflect on Parsifal and its various resonances in Canadian music history. This article will consider three aspects of Parsifal and Canada: 1) a performance history, including both excerpts and complete presentations; 2) remarks on some Canadian singers who have sung Parsifal roles; and 3) Canadian scholarship on Parsifal. NB: The indication [DS] refers the reader to sources that are reproduced in the documentation portfolio that accompanies this article. -

Adolphe Appia and the Emergence of Scenography’ by Professor Thea Brejzek Goethe Institut, Woollahra

Sunday 18 April 2021, 2:00 pm ‘Adolphe Appia and the emergence of scenography’ by Professor Thea Brejzek Goethe Institut, Woollahra Program: 12.30pm: DVD - Ludwig II Castles in Bavaria 2.00pm: Professor Thea Brejzek talks about revolutionary Swiss stage designer Adophe Appia and the Emergence of Scenography 3.30pm: Afternoon tea Goethe Institut, 90 Ocean Street, Woollahra Members $25 / non-members $30 / full-time students $10 Report On Sunday 18 April an enthusiastic group of 40 members and friends gathered at the Goethe Institut for the first time in 18 months to watch a DVD and listen to a talk. We were warmly welcomed by the Director of the Institut, Sonja Griegoschewski, who congratulated the Society on reaching our 40th anniversary. We have been using the Institut as our base for 30 years and Sonja expressed the wish that we will continue for another 40. The talk was followed by refreshments provided by members of the committee plus champagne very generously provided by Sonja. ADOLPHE APPIA AND THE EMERGENCE OF SCENOGRAPHY Professor Thea Brejzek, Professor in Interior Architecture at the University of Technology Sydney Prof Brejzek started with the influence on the theoretical writings of Adolphe Appia (1862 – 1928) of Wagner’s proposal in Artwork of the Future (1849) for a Gesamtkunstwerk (total artwork). In turn Appia’s ideas influenced Wieland Wagner’s restaging of the operas in Bayreuth after the war. She talked about Appia’s early reactions to Bayreuth’s staging and his designs for Tristan and Parsifal. His revolutionary use of lighting and new technology to create atmosphere to support the actor changed the practice of scenography forever. -

Música Y Pasión De Cosima Liszt Y Richard Wagner

A6 [email protected] VIDA SOCIAL JUEVES 14 DE MAYO DE 2020 Música y pasión de Cosima Liszt y Richard Wagner GRACIELA ALMENDRAS Fundado en 1876, l Festival de Bayreuth, que cada año se el festival realiza en julio, no solo hace noticia por su también E obligada cancelación a causa de la pande- suspendió mia, sino que también porque es primera vez en sus funcio- sus más de 140 años de historia que un Wagner nes durante no encabeza su organización. Ocurre que la bisnie- las grandes ta de Richard Wagner, el compositor alemán guerras. En precursor de este festival, está enferma y abando- julio iba a nó su cargo por un tiempo indefinido. celebrar su La historia de este evento data de 1870, cuando 109ª edi- Richard Wagner con su mujer, Cosima Liszt, visita- ción. En la ron la ciudad alemana de Bayreuth y consideraron foto, el que debía construirse un teatro más amplio, capaz teatro. de albergar los montajes y grandes orquestas que requerían las óperas de su autoría. Con el apoyo financiero principalmente de Luis II de Baviera, consiguieron abrir el teatro y su festival en 1876. Entonces, la relación entre Richard Wagner y FESTIVAL DE BAYREUTH su esposa, Cosima, seguía siendo mal vista: ella era 24 años menor que él e hija de uno de sus amigos, y habían comenzado una relación estando ambos casados. Pero a ellos eso poco les importó y juntos crearon un imperio en torno a la música. Cosima Liszt y Richard Wagner. En 1857, Cosima se casó con el pianista y Cosima Liszt (en la director de foto) nació en orquesta Bellagio, Italia, en alemán Hans 1837, hija de la con- von Bülow desa francoalemana (arriba), Marie d’Agoult y de alumno de su su amante, el conno- padre y amigo tado compositor de Wagner. -

Nietzsche and Aestheticism

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 1992 Nietzsche and Aestheticism Brian Leiter Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Brian Leiter, "Nietzsche and Aestheticism," 30 Journal of the History of Philosophy 275 (1992). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Notes and Discussions Nietzsche and Aestheticism 1o Alexander Nehamas's Nietzsche: L~fe as Literature' has enjoyed an enthusiastic reception since its publication in 1985 . Reviewed in a wide array of scholarly journals and even in the popular press, the book has won praise nearly everywhere and has already earned for Nehamas--at least in the intellectual community at large--the reputation as the preeminent American Nietzsche scholar. At least two features of the book may help explain this phenomenon. First, Nehamas's Nietzsche is an imaginative synthesis of several important currents in recent Nietzsche commentary, reflecting the influence of writers like Jacques Der- rida, Sarah Kofman, Paul De Man, and Richard Rorty. These authors figure, often by name, throughout Nehamas's book; and it is perhaps Nehamas's most important achievement to have offered a reading of Nietzsche that incorporates the insights of these writers while surpassing them all in the philosophical ingenuity with which this style of interpreting Nietzsche is developed. The high profile that many of these thinkers now enjoy on the intellectual landscape accounts in part for the reception accorded the "Nietzsche" they so deeply influenced. -

IN SUMMER Lucerne Is a Wagner City

Der Ring des Nibelungen IN SUMMER Lucerne is a Wagner city. For six years – from 1866 to 1872 – the com- poser resided at the Villa Tribschen. This was a decisive period for him artistically as well as personally. It was here that he completed Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg and resumed work on The Ring of the Nibelung, composing both the third act of Siegfried and Götterdäm- merung. Wagner’s Lucerne years also represented a turning point in his personal life. He moved into his new home on Lake Lucerne with Cosima von Bülow, whom he then married on 25 August 1870 in the Protestant parish church. And it was in Tribschen that two of the couple’s three children – their daughter Eva and son Siegfried – were born. To mark the composer’s 200th birthday, LUCERNE FESTIVAL is presenting the first complete performance of theRing cycle in the Wagner city of Lucerne, with the English conductor Jonathan Nott, the Bamberg Symphony Orchestra, and internationally acclaimed Wagner singers, including Albert Dohmen as Wotan, the ruler of the gods, Petra Lang making her role debut as Brünnhilde, Torsten Kerl as Siegfried, Klaus Florian Vogt in the role of Siegmund, and the Russian bass Mikhail Petrenko in a threefold assignment as Fafner, Hunding, and Hagen. This concert presentation of the epoch-making work will enable us to focus on Wagner the musical revolutionary. The highly acclaimed acoustics of the KKL Lucerne’s Salle blanche concert hall will bring out the sonic details and nuances of Wagner’s astounding orchestration with a transparency that has not been heard before. -

International Richard Wagner Congress – Bonn 23Rd to 27Th September 2020

International Richard Wagner Congress – Bonn 23rd to 27th September 2020 Imprint The Richard Wagner Congress 2020 Richard-Wagner-Verband Bonn e.V. programme Andreas Loesch (Vorsitzender) John Peter (stellv. Vorsitzender) was created in collaboration with Zanderstraße 47, 53177 Bonn Tel. +49-(0)178-8539559 [email protected] Organiser / booking details ARS MUSICA Musik- und Kulturreisen GmbH Bachemer Straße 209, 50935 Köln Tel: +49-(0)221-16 86 53 00 Fax: +49-(0)221-16 86 53 01 [email protected] RICHARD-WAGNER-VERBAND BONN E.V. and is sponsored by Image sources frontpage from left to right, from top to bottom - Richard-Wagner-Verband Bonn - Michael Sondermann/Bundesstadt Bonn - Deutsche Post / Richard-Wagner-Verband Bonn - StadtMuseum Bonn - Michael Sondermann/Bundesstadt Bonn - Beethovenhaus Bonn - Stadt Königswinter - Michael Sondermann/Bundesstadt Bonn - Stadtmuseum Siegburg - Michael Sondermann/Bundesstadt Bonn - Michael Sondermann/Bundesstadt Bonn Current information about the program backpage - Michael Sondermann/Bundesstadt Bonn rwv-bonn.de/kongress-2020 Congress Programme for all Congress days 2 p.m. | Gustav-Stresemann-Institut Dear Members of the Richard Wagner Societies, dear Friends of Richard Wagner’s Music, Conference Hotel Hilton Richard Wagner – en miniature Symposium: »Beethoven, Wagner and the political “Welcome” to the Congress of the International Association of Richard Wagner Societies in 2020, commemorating Ludwig “Der Meister” depicted on stamps movements of their time « (simultaneous translation) van Beethoven’s 250th birthday worldwide. Richard Wagner appreciated him more than any other composer in his life, which Prof. Dr. Dieter Borchmeyer, PD Dr. Ulrike Kienzle, is why the Congress in Bonn, Beethoven’s hometown, is going to centre on “Beethoven and Wagner”. -

Wagner and Bayreuth Mendelssohn-Bartholdy and Berlin Brahms and Detmold

MUSIC DOCUMENTARY 30 MIN. VERSIONS Wagner and Bayreuth Arabic, English, French, German, Portuguese, Spanish (01 x 30 min.) No city in the world is so closely identified with a composer as Bayreuth is with Richard Wag- ner. Towards the end of the 19th century Richard Wagner had a Festival Theatre built here and RIGHTS revived the Ancient Greek idea of annual festivals. Nowadays, these festivals are attended by Worldwide, VOD, Mobile around 60,000 people. ORDER NUMBER 66 3238 VERSIONS Mendelssohn-Bartholdy and Berlin Arabic, English, French, German, Portuguese, Spanish (01 x 30 min.) Felix Mendelssohn, one of the most important composers of the 19th century, was influenced decisively by Berlin, which gave shape to the form and development of his music. The televi- RIGHTS sion documentary traces Mendelssohn’s life in the Berlin of the 19th century, as well as show- Worldwide, VOD, Mobile ing the city today. ORDER NUMBER 66 3305 VERSIONS Brahms and Detmold Arabic, English, French, German, Portuguese, Spanish (01 x 30 min.) Around the middle of the 19th century Detmold, a small town in the west of Germany, was a centre of the sort of cultural activity that would normally be expected only of a large city. An RIGHTS artistically-minded local prince saw to it that famous artists came to Detmold and performed in Worldwide, VOD, Mobile the theatre or at his court. For several years the town was the home of composer Johannes Brahms. Here, as Court Musician, he composed some of his most beautiful vocal and instru- ORDER NUMBER ment works. 66 3237 dw-transtel.com Classics | DW Transtel. -

Inside the Ring: Essays on Wagner's Opera Cycle

Inside the Ring: Essays on Wagner’s Opera Cycle John Louis DiGaetani Professor Department of English and Freshman Composition James Morris as Wotan in Wagner’s Die Walküre. Photo: Jennifer Carle/The Metropolitan Opera hirty years ago I edited a book in the 1970s, the problem was finding a admirer of Hitler and she turned the titled Penetrating Wagner’s Ring: performance of the Ring, but now the summer festival into a Nazi showplace An Anthology. Today, I find problem is finding a ticket. Often these in the 1930s and until 1944 when the myself editing a book titled Ring cycles — the four operas done festival was closed. But her sons, Inside the Ring: Essays on within a week, as Wagner wanted — are Wieland and Wolfgang, managed to T Wagner’s Opera Cycle — to be sold out a year in advance of the begin- reopen the festival in 1951; there, published by McFarland Press in spring ning of the performances, so there is Wieland and Wolfgang’s revolutionary 2006. Is the Ring still an appropriate clearly an increasing demand for tickets new approaches to staging the Ring and subject for today’s audiences? Absolutely. as more and more people become fasci- the other Wagner operas helped to In fact, more than ever. The four operas nated by the Ring cycle. revive audience interest and see that comprise the Ring cycle — Das Wagnerian opera in a new visual style Rheingold, Die Walküre, Siegfried, and Political Complications and without its previous political associ- Götterdämmerung — have become more ations. Wieland and Wolfgang Wagner and more popular since the 1970s. -

Philosophy and Critical Theory

STANFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS PHILOSOPHY AND CRITICAL THEORY 20% DISCOUNT ON ALL TITLES 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS The Complete Works of Friedrich Nietzsche .......... 2-3 Political Philosophy ................ 3-5 Ethics and Moral Philosophy ..................................5-6 Phenomenology and Critical Theory ..........................6-8 Meridian: Crossing Aesthetics ...................................8-9 Cultural Memory in the Present .................................9-11 Now in Paperback ....................... 11 Examination Copy Policy ........ 11 The Case of Wagner / Unpublished Fragments ORDERING Twilight of the Idols / from the Period of Human, Use code S21PHIL to receive a 20% discount on all ISBNs The Antichrist / Ecce Homo All Too Human I (Winter listed in this catalog. / Dionysus Dithyrambs / 1874/75–Winter 1877/78) Visit sup.org to order online. Visit Nietzsche Contra Wagner Volume 12 sup.org/help/orderingbyphone/ Volume 9 Friedrich Nietzsche for information on phone Translated, with an Afterword, orders. Books not yet published Friedrich Nietzsche Edited by Alan D. Schrift, by Gary Handwerk or temporarily out of stock will be Translated by Adrian Del Caro, Carol charged to your credit card when This volume presents the first English Diethe, Duncan Large, George H. they become available and are in Leiner, Paul S. Loeb, Alan D. Schrift, translations of Nietzsche’s unpublished the process of being shipped. David F. Tinsley, and Mirko Wittwar notebooks from the years in which he developed the mixed aphoristic- The year 1888 marked the last year EXAMINATION COPY POLICY essayistic mode that continued across of Friedrich Nietzsche’s intellectual the rest of his career. These notebooks Examination copies of select titles career and the culmination of his comprise a range of materials, includ- are available on sup.org. -

Premières Principali All 'Opéra-Comique

Premières principali all ’Opéra-Comique Data Compositore Titolo 30 luglio 1753 Antoine Dauvergne Les troqueurs 26 luglio 1757 Egidio Romualdo Duni Le peintre amoureux de son modèle 9 marzo 1759 François-André Danican Philidor Blaise le savetier 22 agosto 1761 François-André Danican Philidor Le maréchal ferrant 14 settembre 1761 Pierre-Alexandre Monsigny On ne s ’avise jamais de tout 22 novembre 1762 Pierre-Alexandre Monsigny Le roy et le fermier 27 febbraio 1765 François-André Danican Philidor Tom Jones 20 agosto 1768 André Grétry Le Huron 5 gennaio 1769 André Grétry Lucile 6 marzo 1769 Pierre-Alexandre Monsigny Le déserteur 20 settembre 1769 André Grétry Le tableau parlant 16 dicembre 1771 André Grétry Zémire et Azor 12 giugno 1776 André Grétry Les mariages samnites 3 gennaio 1780 André Grétry Aucassin et Nicolette 21 ottobre 1784 André Grétry Richard Coeur-de-lion 4 agosto 1785 Nicolas Dalayrac L ’amant statue 15 maggio 1786 Nicolas Dalayrac Nina, ou La folle par amour 14 gennaio 1789 Nicolas Dalayrac Les deux petits savoyards 4 settembre 1790 Étienne Méhul Euphrosine 15 gennaio 1791 Rodolphe Kreutzer Paolo e Virginia 9 aprile 1791 André Grétry Guglielmo Tell 3 maggio 1792 Étienne Méhul Stratonice 6 maggio 1794 Étienne Méhul Mélidore et Phrosine 11 ottobre 1799 Étienne Méhul Ariodant 23 ottobre 1800 Nicolas Dalayrac Maison à vendre 16 settembre 1801 François-Adrien Boieldieu Le calife de Bagdad 17 maggio 1806 Étienne Méhul Uthal 17 febbraio 1807 Étienne Méhul Joseph 9 maggio 1807 Nicolas Isouard Les rendez-vous bourgeois 22 febbraio -

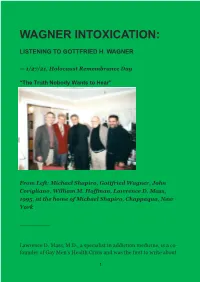

Wagner Intoxication

WAGNER INTOXICATION: LISTENING TO GOTTFRIED H. WAGNER — 1/27/21, Holocaust Remembrance Day “The Truth Nobody Wants to Hear” From Left: Michael Shapiro, Gottfried Wagner, John Corigliano, William M. Hoffman, Lawrence D. Mass, 1995, at the home of Michael Shapiro, Chappaqua, New York _________ Lawrence D. Mass, M.D., a specialist in addiction medicine, is a co- founder of Gay Men’s Health Crisis and was the first to write about 1 AIDS for the press. He is the author of We Must Love One Another or Die: The Life and Legacies of Larry Kramer. He is completing On The Future of Wagnerism, a sequel to his memoir, Confessions of a Jewish Wagnerite. For additional biographical information on Lawrence D. Mass, please see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lawrence_D._Mass Larry Mass: For Gottfried Wagner, my work on Wagner, art and addiction struck an immediate chord of recognition. I was trying to describe what Gottfried has long referred to as “Wagner intoxication.” In fact, he thought this would make a good title for my book. The subtitle he suggested was taken from the title of his Foreword to my Confessions of a Jewish Wagnerite: “Redemption from Wagner the redeemer: some introductory thoughts on Wagner’s anti- semitism.” The meaning of this phrase, “redemption from the redeemer,” taken from Nietzsche, is discussed in the interview with Gottfried that follows these reflections. Like me, Gottfried sees the world of Wagner appreciation as deeply affected by a cultish devotion that from its inception was cradling history’s most irrational and extremist mass-psychological movement. -

University of New South Wales 2005 UNIVERSITY of NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Project Report Sheet

BÜRGERTUM OHNE RAUM: German Liberalism and Imperialism, 1848-1884, 1918-1943. Matthew P Fitzpatrick A thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales 2005 UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Project Report Sheet Surname or Family name: Fitzpatrick First name: Matthew Other name/s: Peter Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: PhD. School: History Faculty: Arts Title: Bürgertum Ohne Raum: German Liberalism and Imperialism 1848-1884, 1918-1943. Abstract This thesis situates the emergence of German imperialist theory and praxis during the nineteenth century within the context of the ascendancy of German liberalism. It also contends that imperialism was an integral part of a liberal sense of German national identity. It is divided into an introduction, four parts and a set of conclusions. The introduction is a methodological and theoretical orientation. It offers an historiographical overview and places the thesis within the broader historiographical context. It also discusses the utility of post-colonial theory and various theories of nationalism and nation-building. Part One examines the emergence of expansionism within liberal circles prior to and during the period of 1848/ 49. It examines the consolidation of expansionist theory and political practice, particularly as exemplified in the Frankfurt National Assembly and the works of Friedrich List. Part Two examines the persistence of imperialist theorising and praxis in the post-revolutionary era. It scrutinises the role of liberal associations, civil society, the press and the private sector in maintaining expansionist energies up until the 1884 decision to establish state-protected colonies. Part Three focuses on the cultural transmission of imperialist values through the sciences, media and fiction.