Four Quarters Volume 14 Number 3 Four Quarters: March 1965 Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report R E Sumes

REPORT R E SUMES ED 012 802 24 AA 000 162 MODEL FOR AN ADVANCED PLACEMENT ENGLISH COURSE. BY- HART, JOHN A. HAYES, ANN L. CARNEGIE INST. OF TECH., PITTSBURGH, PA. REPORT NUMBER BR-6-8210-1 PUB DATE JAN 67 MRS PRICE MF -$1.O0 HC-$8.2S 201P. DESCRIPTORS- *ENGLISH INSTRUCTION, *ACCELERATED COURSES, DISCUSSION (TEACHING TECHNIQUE), *DISCUSSION PROGRAMS, *COMPOSITION SKILLS (LITERARY), ENRICHMENT PROGRAMS, CRITICAL READING, *TEACHING TECHNIQUES, THE DESIGN OF THIS COURSE WAS BASED ON THE BELIEF THAT GOOD DISCUSSION IS A WAY TO INCREASE UNDERSTANDING. ALTHOUGH THE COURSE IS PRESENTED IN DETAILED FORM, LIKE A SYLLABUS, IT WAS NOT INTENDED EY THE AUTHORS TO BE RIGIDLY FOLLOWED LIKE A SCHEDULE BUT, INSTEAD, TO BE USED AS A FRAMEWORK TO HELP THE TEACHER IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF A DISCUSSION COURSE. THE PLAN CALLS FOR 2 DAYS A WEEK TO BE DEVOTED TO DISCUSSION OF WRITING, TO IN-CLASS WRITING ASSIGNMENTS, AND TO CRITICISM OF STUDENTS' WRITING BY THE TEACHER AND THE CLASS. PLANS FOR HOMEWORK WRITING ASSIGNMENTS ARE INCLUDED. THE DISCUSSION SESSIONS PLANNED FOR THE OTHER 3 DAYS A WEEK ARE CENTERED AROUND READINGS ORGANIZED BY GENRE, OR THE KIND OF WRITING OF THE SELECTION. THE READINGS CONSIST OF SELECTIONS FROM NARRATION, POETRY, SATIRE, AND FICTION. (AL) : /MODEL FOR AN ADVANCED PLACEMENT ENGLISH COURSE John A. Hart Ann L. Hayes Carnegie Institute of Technology Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania January, 1967 2 An Advanced Placement English course. A most useful description of the Advanced Placement English course, given in general terms, is provided by the Committee of Examiners for English in Advanced Placement Program: 1966-68 Course Descriptions, put out by the College Entrance Examination Board and available from them at 475 Riverside Drive, New York, N.Y. -

American Literature in Transition, 1930–1940 Edited by Ichiro Takayoshi Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42938-2 — American Literature in Transition, 1930–1940 Edited by Ichiro Takayoshi Frontmatter More Information AMERICAN LITERATURE IN TRANSITION, 1930–1940 American Literature in Transition, 1930–1940 gathers together in a single volume preeminent critics and historians to offer an author- itative, analytic, and theoretically advanced account of the Depression era’s key literary events. Many topics of canonical importance, such as protest literature, Hollywood fiction, the culture industry, and popu- lism, receive fresh treatment. The book also covers emerging areas of interest, such as radio drama, bestsellers, religious fiction, interna- tionalism, and middlebrow domestic fiction. Traditionally, scholars have treated each one of these issues in isolation. This volume situates all the significant literary developments of the 1930s within a single and capacious vision that discloses their hidden structural relations – their contradictions, similarities, and reciprocities. This is an excellent resource for undergraduate and graduate students, and for scholars interested in American literary culture of the 1930s. ichiro takayoshi teaches modern American literature and social thought at Tufts University. He is the author of American Writers and the Approach of World War II, 1935–1941: A Literary History (Cambridge University Press, 2015) and editor of American Literature in Transition, 1920–1930 (Cambridge University Press, 2017). He is currently at work on a literary and intellectual history of the interwar decades. © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42938-2 — American Literature in Transition, 1930–1940 Edited by Ichiro Takayoshi Frontmatter More Information american literature in transition American Literature in Transition captures the dynamic energies transmitted across the 20th- and 21st-century American literary landscapes. -

The Pulitzer Prize for Fiction Honors a Distinguished Work of Fiction by an American Author, Preferably Dealing with American Life

Pulitzer Prize Winners Named after Hungarian newspaper publisher Joseph Pulitzer, the Pulitzer Prize for fiction honors a distinguished work of fiction by an American author, preferably dealing with American life. Chosen from a selection of 800 titles by five letter juries since 1918, the award has become one of the most prestigious awards in America for fiction. Holdings found in the library are featured in red. 2017 The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead 2016 The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen 2015 All the Light we Cannot See by Anthony Doerr 2014 The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt 2013: The Orphan Master’s Son by Adam Johnson 2012: No prize (no majority vote reached) 2011: A visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan 2010:Tinkers by Paul Harding 2009:Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout 2008:The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz 2007:The Road by Cormac McCarthy 2006:March by Geraldine Brooks 2005 Gilead: A Novel, by Marilynne Robinson 2004 The Known World by Edward Jones 2003 Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides 2002 Empire Falls by Richard Russo 2001 The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay by Michael Chabon 2000 Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri 1999 The Hours by Michael Cunningham 1998 American Pastoral by Philip Roth 1997 Martin Dressler: The Tale of an American Dreamer by Stephan Milhauser 1996 Independence Day by Richard Ford 1995 The Stone Diaries by Carol Shields 1994 The Shipping News by E. Anne Proulx 1993 A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain by Robert Olen Butler 1992 A Thousand Acres by Jane Smiley -

Pulitzer Prize

1946: no award given 1945: A Bell for Adano by John Hersey 1944: Journey in the Dark by Martin Flavin 1943: Dragon's Teeth by Upton Sinclair Pulitzer 1942: In This Our Life by Ellen Glasgow 1941: no award given 1940: The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck 1939: The Yearling by Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings Prize-Winning 1938: The Late George Apley by John Phillips Marquand 1937: Gone with the Wind by Margaret Mitchell 1936: Honey in the Horn by Harold L. Davis Fiction 1935: Now in November by Josephine Winslow Johnson 1934: Lamb in His Bosom by Caroline Miller 1933: The Store by Thomas Sigismund Stribling 1932: The Good Earth by Pearl S. Buck 1931 : Years of Grace by Margaret Ayer Barnes 1930: Laughing Boy by Oliver La Farge 1929: Scarlet Sister Mary by Julia Peterkin 1928: The Bridge of San Luis Rey by Thornton Wilder 1927: Early Autumn by Louis Bromfield 1926: Arrowsmith by Sinclair Lewis (declined prize) 1925: So Big! by Edna Ferber 1924: The Able McLaughlins by Margaret Wilson 1923: One of Ours by Willa Cather 1922: Alice Adams by Booth Tarkington 1921: The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton 1920: no award given 1919: The Magnificent Ambersons by Booth Tarkington 1918: His Family by Ernest Poole Deer Park Public Library 44 Lake Avenue Deer Park, NY 11729 (631) 586-3000 2012: no award given 1980: The Executioner's Song by Norman Mailer 2011: Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan 1979: The Stories of John Cheever by John Cheever 2010: Tinkers by Paul Harding 1978: Elbow Room by James Alan McPherson 2009: Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout 1977: No award given 2008: The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz 1976: Humboldt's Gift by Saul Bellow 2007: The Road by Cormac McCarthy 1975: The Killer Angels by Michael Shaara 2006: March by Geraldine Brooks 1974: No award given 2005: Gilead by Marilynne Robinson 1973: The Optimist's Daughter by Eudora Welty 2004: The Known World by Edward P. -

October 4, 2016 (XXXIII:6) Joseph L. Mankiewicz: ALL ABOUT EVE (1950), 138 Min

October 4, 2016 (XXXIII:6) Joseph L. Mankiewicz: ALL ABOUT EVE (1950), 138 min All About Eve received 14 Academy Award nominations and won 6 of them: picture, director, supporting actor, sound, screenplay, costume design. It probably would have won two more if four members of the cast hasn’t been in direct competition with one another: Davis and Baxter for Best Actress and Celeste Holm and Thelma Ritter for Best Supporting Actress. The story is that the studio tried to get Baxter to go for Supporting but she refused because she already had one of those and wanted to move up. Years later, the same story goes, she allowed as maybe she made a bad career move there and Bette David allowed as she was finally right about something. Directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz Written by Joseph L. Mankiewicz (screenplay) Mary Orr (story "The Wisdom of Eve", uncredited) Produced by Darryl F. Zanuck Music Alfred Newman Cinematography Milton R. Krasner Film Editing Barbara McLean Art Direction George W. Davis and Lyle R. Wheeler Eddie Fisher…Stage Manager Set Decoration Thomas Little and Walter M. Scott William Pullen…Clerk Claude Stroud…Pianist Cast Eugene Borden…Frenchman Bette Davis…Margo Channing Helen Mowery…Reporter Anne Baxter…Eve Harrington Steven Geray…Captain of Waiters George Sanders…Addison DeWitt Celeste Holm…Karen Richards Joseph L. Mankiewicz (b. February 11, 1909 in Wilkes- Gary Merrill…Bill Simpson Barre, Pennsylvania—d. February 5, 1993, age 83, in Hugh Marlowe…Lloyd Richards Bedford, New York) started in the film industry Gregory Ratoff…Max Fabian translating intertitle cards for Paramount in Berlin. -

PULITZER PRIZE WINNERS in LETTERS © by Larry James

PULITZER PRIZE WINNERS IN LETTERS © by Larry James Gianakos Fiction 1917 no award *1918 Ernest Poole, His Family (Macmillan Co.; 320 pgs.; bound in blue cloth boards, gilt stamped on front cover and spine; full [embracing front panel, spine, and back panel] jacket illustration depicting New York City buildings by E. C.Caswell); published May 16, 1917; $1.50; three copies, two with the stunning dust jacket, now almost exotic in its rarity, with the front flap reading: “Just as THE HARBOR was the story of a constantly changing life out upon the fringe of the city, along its wharves, among its ships, so the story of Roger Gale’s family pictures the growth of a generation out of the embers of the old in the ceaselessly changing heart of New York. How Roger’s three daughters grew into the maturity of their several lives, each one so different, Mr. Poole tells with strong and compelling beauty, touching with deep, whole-hearted conviction some of the most vital problems of our modern way of living!the home, motherhood, children, the school; all of them seen through the realization, which Roger’s dying wife made clear to him, that whatever life may bring, ‘we will live on in our children’s lives.’ The old Gale house down-town is a little fragment of a past generation existing somehow beneath the towering apartments and office-buildings of the altered city. Roger will be remembered when other figures in modern literature have been forgotten, gazing out of his window at the lights of some near-by dwelling lifting high above his home, thinking -

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/113624 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2017-12-06 and may be subject to change. VINCENT PIKET Louis Auchincloss he Growth of a Novelist European University Press LOUIS AUCHINCLOSS THE GROWTH OF A NOVELIST LOUIS AUCHINCLOSS THE GROWTH OF A NOVELIST Een wetenschappelijke proeve op het gebied van de letteren PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Katholieke Universiteit te Nijmegen, volgens besluit van het college van decanen in het openbaar te verdedigen op woensdag 5 april, 1989 des namiddags te 1.30 uur precies door VINCENT PIKET geboren op 12 juli 1959 te Nijmegen EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY PRESS NIJMEGEN 1989 Promotor: Prof. dr. G.A.M. Janssens Privately printed and distributed by: European University Press P.O. Box 1052 6501 BB Nijmegen The Netherlands Photograph by courtesy of Houghton Mifflin Company Copyright Vincent Plket, 1989 CIP Data Koninklijke Bibliotheek, The Hague Plket, Vincent Louis Auchincloss : The Growth of a novelist / Vincent Plket. - Nijmegen : European University Press Ook verschenen in handelseditie: Nijmegen : European University Press, 1989. - Proefschrift Nijmegen. Incl. bibliogr. ISBN 90-72897-02-1 SISO enge-a 856.6 UDC 929 Auchincloss, Louis Stanton+820(73)n19,,(043.3) NUGI 953 Trefw.: Auchincloss, Louis Stanton. CONTENTS Acknowledgments lil Introduction 1 -

Item More Personal, More Unique, And, Therefore More Representative of the Experience of the Book Itself

Q&B Quill & Brush (301) 874-3200 Fax: (301)874-0824 E-mail: [email protected] Home Page: http://www.qbbooks.com A dear friend of ours, who is herself an author, once asked, “But why do these people want me to sign their books?” I didn’t have a ready answer, but have reflected on the question ever since. Why Signed Books? Reading is pure pleasure, and we tend to develop affection for the people who bring us such pleasure. Even when we discuss books for a living, or in a book club, or with our spouses or co- workers, reading is still a very personal, solo pursuit. For most collectors, a signature in a book is one way to make a mass-produced item more personal, more unique, and, therefore more representative of the experience of the book itself. Few of us have the opportunity to meet the authors we love face-to-face, but a book signed by an author is often the next best thing—it brings us that much closer to the author, proof positive that they have held it in their own hands. Of course, for others, there is a cost analysis, a running thought-process that goes something like this: “If I’m going to invest in a book, I might as well buy a first edition, and if I’m going to invest in a first edition, I might as well buy a signed copy.” In other words we want the best possible copy—if nothing else, it is at least one way to hedge the bet that the book will go up in value, or, nowadays, retain its value. -

Award Winners

Award Winners Agatha Awards 1989 Naked Once More by 2000 The Traveling Vampire Show Best Contemporary Novel Elizabeth Peters by Richard Laymon (Formerly Best Novel) 1988 Something Wicked by 1999 Mr. X by Peter Straub Carolyn G. Hart 1998 Bag Of Bones by Stephen 2017 Glass Houses by Louise King Penny Best Historical Novel 1997 Children Of The Dusk by 2016 A Great Reckoning by Louise Janet Berliner Penny 2017 In Farleigh Field by Rhys 1996 The Green Mile by Stephen 2015 Long Upon The Land by Bowen King Margaret Maron 2016 The Reek of Red Herrings 1995 Zombie by Joyce Carol Oates 2014 Truth Be Told by Hank by Catriona McPherson 1994 Dead In the Water by Nancy Philippi Ryan 2015 Dreaming Spies by Laurie R. Holder 2013 The Wrong Girl by Hank King 1993 The Throat by Peter Straub Philippi Ryan 2014 Queen of Hearts by Rhys 1992 Blood Of The Lamb by 2012 The Beautiful Mystery by Bowen Thomas F. Monteleone Louise Penny 2013 A Question of Honor by 1991 Boy’s Life by Robert R. 2011 Three-Day Town by Margaret Charles Todd McCammon Maron 2012 Dandy Gilver and an 1990 Mine by Robert R. 2010 Bury Your Dead by Louise Unsuitable Day for McCammon Penny Murder by Catriona 1989 Carrion Comfort by Dan 2009 The Brutal Telling by Louise McPherson Simmons Penny 2011 Naughty in Nice by Rhys 1988 The Silence Of The Lambs by 2008 The Cruelest Month by Bowen Thomas Harris Louise Penny 1987 Misery by Stephen King 2007 A Fatal Grace by Louise Bram Stoker Award 1986 Swan Song by Robert R. -

Pulitzer Lit P 2020

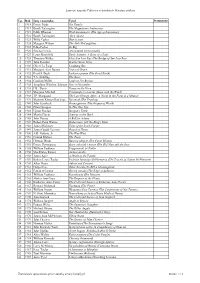

Laureaci nagrody Pulitzera w dziedzinie literatury pi ęknej Lp. Rok Imi ę i nazwisko Tytuł Przeczytane 1 1918 Ernest Poole His Family 2 1919 Booth Tarkington The Magnificent Ambersons 3 1921 Edith Wharton Wiek niewinno ści (The Age of Innocence) 4 1922 Booth Tarkington Alice Adams 5 1923 Willa Cather One of ours 6 1924 Margaret Wilson The Able McLaughlins 7 1925 Edna Ferber So Big 8 1926 Sinclair Lewis Arrowsmith (Arrowsmith) 9 1927 Louis Bromfield Early Autumn: A Story of a Lady 10 1928 Thornton Wilder Most San Luis Rey (The Bridge of San Luis Rey) 11 1929 Julia Peterkin Scarlet Sister Mary 12 1930 Oliver La Farge Laughing Boy 13 1931 Margaret Ayer Barnes Years of Grace 14 1932 Pearl S. Buck Łaskawa ziemia (The Good Earth) 15 1933 T.S. Stribling The Store 16 1934 Caroline Miller Lamb in His Bosom 17 1935 Josephine Winslow Johnson Now in November 18 1936 H.L. Davis Honey in the Horn 19 1937 Margaret Mitchell Przemin ęło z wiatrem (Gone with the Wind) 20 1938 J.P. Marquand The Late George Apley: A Novel in the Form of a Memoir 21 1939 Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings Roczniak (The Yearling) 22 1940 John Steinbeck Grona gniewu (The Grapes of Wrath) 23 1942 Ellen Glasgow In This Our Life 24 1943 Upton Sinclair Dragon's Teeth 25 1944 Martin Flavin Journey in the Dark 26 1945 John Hersey A Bell for Adano 27 1947 Robert Penn Warren Gubernator (All the King's Men) 28 1948 James Michener Tales of the South Pacific 29 1949 James Gould Cozzens Guard of Honor 30 1950 A.B. -

Printer Friendly Version

401 Plainfield Rd., Darien, IL 60561 T (630) 887.8760 F (630) 887.8801 ippl.info facebook.com/ipplinfo twitter.com/ipplinfo Book Discussion Retro Books from the Last Century to Intrigue Your Book Group Ray Bradbury Sinclair Lewis Nevil Shute Dandelion Wine Main Street On the Beach Novel Bradbury Novel Lewis Novel Shute PB Classic Bradbury Hoopla (audio/ebook) Large Type Novel Bradbury Betty Smith eMediaLibrary (ebook) John P. Marquand A Tree Grows in Brooklyn Hoopla (audio) The Late George Apley Novel Smith Novel Marquand Large Type Novel Smith Pearl S. Buck eMediaLibrary (audio) The Good Earth James Michener eReadIllinois (ebook) Novel Buck Tales of the South Pacific PB Classic Buck Novel Michener Muriel Spark eMediaLibrary (audio/ebook) The Prime of Miss Jean Hoopla (audio/ebook) Alan Paton Brodie Cry, the Beloved Country Novel Spark Robertson Davies Novel Paton eMediaLibrary (audio) Fifth Business Hoopla (audio) Hoopla (audio/ebook) Novel Davies Chaim Potok Wallace Stegner Daphne DuMaurier The Chosen Crossing to Safety Rebecca Novel Potok Novel Stegner Novel DuMaurier CD Novel Potok CD Novel Stegner Large Type Novel DuMaurier eMediaLibrary (ebook) eMediaLibrary (audio) Barbara Pym Excellent Women Booth Tarkington Edna Ferber Novel Pym The Magnificent Ambersons So Big Hoopla (audio) Novel Tarkington Novel Ferber Margery Kinnan Rawlings Mildred Walker Richard Hughes The Yearling Winter Wheat A High Wind in Jamaica Novel Rawlings Novel Walker Novel Hughes J Novel Rawlings J Large Type Novel Rawlings DW 2/15, updated MP 8/17 . -

Sunday Night Book Group

SUNDAY NIGHT BOOK GROUP TITLE AUTHOR DATE The Things They Carried Tim O'Brien 09/95 Red Azalea Anchee Min 10/95 A Midwife's Tale Laurel Thatcher Ulrich 11/95 Girl Interrupted Susanna Kaysen Map of the World Jane Hamilton Palace Walk Naguib Maloof The Bird Artist Howard Norman Crossing to Safety Wallace Stegner 9/96 ? 10/96 The Liars Club Mary Karr My Antonia/Death Comes to the Archbishop Willa Carther 01/97 The Cunning Man Robertson Davies 02/97 Portrait of a Lady Henry James 03/97 Having Our Say Sarah & Eliz. Delany 04/96 The Magnificient Spinster May Sarton 01/97 A Civil Action Jonathon Harr 09/97 The Color of Water James McBride 10/97 Hotel du Lac Anita Brookner 12/97 Things Fall Apart Chinua Achebe 01/98 Remembering Babylon David Malouf 02/98 The Country of the Pointed Firs Sarah Orne Jewett 03/98 The Country Doctor Sarah Orne Jewett 03/98 Mrs. Dalloway Virginia Woolf 04/98 Corelli's Mandolin Louis de Bernires 05/98 In the Wilderness Kim Barnes 06/98 Under the Tuscan Sun Frances Mayes 07/98 To the Lighthouse Virginia Woolf 08/98 Their Eyes Were Watching God Zora Neale Hurston 09/98 The God of Small Things Arundhati Roy 10/98 The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down Ann Fadiman 11/98 I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings Maya Angelou 01/99 Miracle at Philadelphia Catherine Drinker Bowen 02/99 Tuesdays With Morrie Mitch Albom 03/99 The People's History of the U.S.