Download, and Redistribute Live Streams Without the Knowledge Or Permission of the Original Creators

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sunday Morning Grid 4/12/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 4/12/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Bull Riding Remembers 2015 Masters Tournament Final Round. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Program Luna! Poppy Cat Tree Fu Figure Skating 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Explore Incredible Dog Challenge 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program Red Lights ›› (2012) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News TBA Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY) Doki Ad Dive, Olly Dive, Olly E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Toluca vs Atlas República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Best Praise Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Hocus Pocus ›› (1993) Bette Midler. -

Technical Skills

Natalie Grace Roman Los Angeles, CA [email protected] portfolio: natalieroman.com Previous Employment: Technical Skills: Studio71 LP - Beverly Hills, CA • Vector and Raster Design/Brand Identity Feb 2015 - May 2020 • Motion Graphics and Visual Effects • Video Post-Production Designer • Basic 3D Printing and Rapid Prototyping Design Team Maintaining Studio71 outward facing brand, visually branding • Laser Cutting/Engraving top-tier YouTube/web talent, motion graphics, show development. • 3D Modeling and Animation • Costume/Prop Fabrication Scripted Development For Ellation/Crunchyroll/VRV as show buyer Software Skills: Initial pitch deck, pilot draft, and worldbuilding groundwork for unannounced animation project in collaboration with Crunchyroll. Collective Digital Studio - Beverly Hills, CA 2015 Spring Intern • Adobe Certified in Illustrator CC Network Development Team • Adobe Certified in Photoshop CC Jan 2015 - Hire, Feb 2015 • Adobe Certified in Premiere CC • Adobe Certified After Effects Ball State University - Muncie, IN Web Developer, Multimedia Content Producer • Proficiency in Adobe Indesign CC Office of Recreation Services • Proficiency in AutoDesk Fusion 360 September 2013 - December 2014 Education: Visual Effects Artist The Digital Corps Ball State University - Muncie, IN August 2012 - May 2013 Bachelor of Arts in Telecommunications Focus in Digital Production, Emerging Media, May 2015 Projects: Studio71, LP Corridor Digital Mr. Mom | Vudu - 2019 Warframe Prop Commission Served as sole VFX Artist on reboot of “Mr. Mom,” building sign Over the period of two months, constructed replicas of hero and screen replacements, and painting out production errors. props from ‘Warframe’ by Digital Extremes using 3D Printing and Arduino microcontrollers. Fetch Me A Date/I Want My Stuff Back | Facebook - 2019 Built motion graphic elements for unscripted Facebook Watch Dude Perfect / Mobcrush formats built around dating/relationships. -

Adult Literacy; Classroom Writing. the Manual Also Provides Tutors with a Variety of Lists for Assessmen

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 367 901 CE 066 097 AUTHOR Clark, John T., Ed.; Williams, Ron, Jr., Ed. TITLE Tutor Reference Manual. Second Edition. INSTITUTION Literacy Network of Greater Cincinnati, OH. SPONS AGENCY Cincinnati Human Services Div., OH.; Ohio State Dept. of Education, Columbus. Div. of Educational Services. PUB DATE Dec 93 NOTE 247p. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adult Basic Education; *Adult Literacy; Classroom Techniques; *Educational Resources; *Literacy Education; Phonics; *Reading Instruction; *Teaching Methods; *Writing Instruction ABSTRACT This manual, intended for use by tutors working with adults learning to read, offers a ,onsolidated resource of specific instructional techniques and provides additional suggestions not covered in basic tutoring workshops. The manual summarizes a variety of approaches commonly used to instruct adults and provides background for three modes of teaching and the process approach to writing. The manual also provides tutors with a variety of lists for use in aiding students to decode and comprehend. The manual is organized in eight sections: (1) the three columns of learning (coaching, discussion, and didactic instruction);(2) teaching methods; (3) teaching writing; (4) instructional systems;(5) goal setting and lesson planning involving students; (6) student reading assessment; (7) working with learning disabled adult students; and (8) word lists for tutoring. Contains 72 references. (KC) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** Literacy Network of Greater ;.1 Cincinnati Tutor Reference Manual Second Edition December, 1993 Literacy Network of Greater Cincinnati 636 West Seventh Q. - Suite 207 Cincinnati, Ohio 46203 "PERMISSION TO REPRODUC!: U S. -

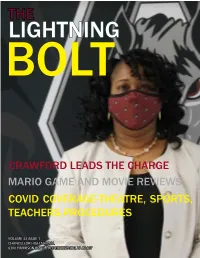

Lightning Bolt

THE LIGHTNING BOLT CRAWFORD LEADS THE CHARGE MARIO GAME AND MOVIE REVIEWS COVID COVERAGE-THEATRE, SPORTS, TEACHERS,PROCEDURES VOLUME 33 iSSUE 1 CHANCELLOR HIGH SCHOOL 6300 HARRISON ROAD, FREDERICKSBURG, VA 22407 1 Sep/Oct 2020 RETIREMENT, RETURN TO SCHOOL, MRS. GATTIE AND CRAWFORD ADVISOR FAITH REMICK Left Mrs. Bass-Fortune is at her retirement parade on June EDITOR-IN-CHIEF 24 that was held to honor her many years at Chancellor High School. For more than three CARA SEELY hours decorated cars drove by the school, honking at Mrs. NEWS EDITOR Bass-Fortune, giving her gifts and well wishes. CARA HADDEN FEATURES EDITOR KAITLYN GARVEY SPORTS EDITOR STEPHANIE MARTINEZ & EMMA PURCELL OP-ED EDITORS Above and Left: Chancellor gets a facelift of decorated doors throughout the school. MIKAH NELSON Front Cover:New Principal Mrs. Cassandra Crawford & Back Cover: Newly Retired HAILEY PATTEN Mrs. Bass-Fortune CHARGING CORNER CHARGER FUR BABIES CONTEST MATCH THE NAME OF THE PET TO THE PICTURE AND TAKE YOUR ANSWERS TO ROOM A113 OR EMAIL LGATTIE@SPOT- SYLVANIA.K12.VA.US FOR A CHANCE TO WIN A PRIZE. HAVE A PHOTO OF YOUR FURRY FRIEND YOU WANT TO SUBMIT? EMAIL SUBMISSIONS TO [email protected]. Charger 1 Charger 2 Charger 3 Charger 4 Names to choose from. Note: There are more names than pictures! Banks, Sadie, Fenway, Bently, Spot, Bear, Prince, Thor, Sunshine, Lady Sep/Oct 2020 2 IS THERE REWARD TO THIS RISK? By Faith Remick school even for two days a many students with height- money to get our kids back Editor-In-Chief week is dangerous, and the ened behavioral needs that to school safely.” I agree. -

Identity / Vlog

Identity Our deeply interconnected social media environment world challenges our understanding of how we fit into the world and demands that we craft and project a personal brand online. We create media, or watch and share it, in order to express and perform our identities and affiliate ourselves with our communities. Affiliative Loop Theater Affiliative videos target micro-audiences by reflecting Working within the constraints of the now-defunct social viewers back to themselves, operating on a level of intimacy video platform Vine, users iterated on a unique kind of and recognition similar to in-jokes. These videos rely on performance that relied on the 6.5-second loop as a defining recognizable phrases and situations, incentivizing viewers to formal element. Fast edits, absurd switches in logic, over-the- share them to their networks to express their own identities. top acting, and nonsensical phrases and situations coined a That affiliative videos cost little to produce allows them to number of memes and found the videos shared far outside target narrowly carved audiences that have not received such their originating platform as Vine compilations. The strange, specialized attention in traditional media. wacky humor was performed for friends and followers on the social network, an expression of self-identity. Shit Girls Say | 1:18 | 2011 | Shit THINGS ONLY TRANS GUYS Girls Say UNDERSTAND | 9:01 | 2016 | Sam Swipe up to scroll through a selection of Vine videos. Shit White Girls Say...to Black Girls | Barnes 2:01 | 2012 | chescaleigh -

Social Media Entertainment Could Be the Future of the Screen Industry, So Let's Not Strangle It with Regulation

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Cunningham, Stuart (2018) Social media entertainment could be the future of the screen industry, so let’s not strangle it with regulation. The Conversation, October, pp. 1-6, 2018. [Article] This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/122330/ c Consult author(s) regarding copyright matters This work is covered by copyright. Unless the document is being made available under a Creative Commons Licence, you must assume that re-use is limited to personal use and that permission from the copyright owner must be obtained for all other uses. If the docu- ment is available under a Creative Commons License (or other specified license) then refer to the Licence for details of permitted re-use. It is a condition of access that users recog- nise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. If you believe that this work infringes copyright please provide details by email to [email protected] License: Creative Commons: Attribution-No Derivative Works 2.5 Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. https:// theconversation.com/ social-media-entertainment-could-be-the-future-of-the-screen-industry-so-lets-not-strangle-it-with-regulation-101037 -

Human Evolution

So we’re about halfway through our series, and 6.0 after five episodes involving no humans whatso- ever, today we are finally going to get some people! HUMAN Mr. Green, Mr. Green! Why are we already at hu- 0:49–1:39 manity? I mean, if we’re covering 13.8 billion years, RISE OF HUMANS shouldn’t humanity come in the last, like, two sec- EVOLUTION onds of the last episode? I mean, humans are totally insignificant compared to the vastness of the uni- verse. Like, we should be checking in on how Jupi- ter’s doing. Fair point, me from the past. Jupiter, by the way, still giant and gassy. There’s two reasons why we focus a little more on humanity in Big History. The selfish reason is that we care about humans in Big History because we are humans. 0:00–0:49 Hi, I’m John Green. Welcome to Crash Course Big We are naturally curious to figure out where we History where today we’re going to talk about the belong in the huge sequence of events beginning OUT OF AFRICA Planet of the Apes films. What’s that? Apparently with the Big Bang. Secondly, humans represent those were not documentaries. a really weird change in the Universe. I mean, so far as we know, we are one of the most complex But there was an evolutionary process that saw things in the cosmos. primates move out of East Africa and transform the Earth into an actual planet of the apes. But Whether you measure complexity in terms of bio- the apes are us. -

The Depiction of Women Characters in John Green's Novels/Prikaz Ženskih Likova U Romanima Johna Greena

The Depiction of Women Characters in John Green's Novels/Prikaz ženskih likova u romanima Johna Greena Nikolašević, Helena Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2018 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:142:605184 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-27 Repository / Repozitorij: FFOS-repository - Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek Sveučilište J.J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Osijek Dvopredmetni sveučilišni preddiplomski studij engleskog jezika i književnosti i mađarskog jezika i književnosti Helena Nikolašević Prikaz ženskih likova u romanima Johna Greena Završni rad Mentorica: izv. prof. dr. sc. Biljana Oklopčić Osijek, 2018. 1 Sveučilište J.J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Osijek Dvopredmetni sveučilišni preddiplomski studij engleskog jezika i književnosti i mađarskog jezika i književnosti Helena Nikolašević Prikaz ženskih likova u romanima Johna Greena Završni rad Znanstveno područje: humanističke znanosti Znanstveno polje: filologija Znanstvena grana: anglistika Mentorica: izv. prof. dr. sc. Biljana Oklopčić Osijek, 2018. 2 J.J. Strossmayer University of Osijek Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Department of English Double Major BA Study Programme in English Language and Literature -

The Evolutionary Epic

The keystone of our story is evolution by natural 0:40–1:36 5.1 selection. So, in the 1830s, a young Charles Darwin traveled around the world on the H.M.S. Beagle. NATURAL SELECTION Inarguably, by the way, the most important beagle THE of all time. I apologize, Snoopy, but it’s true. Dar- win had the rare and amazing opportunity to study a great variety of the world’s wildlife, and upon EVOLUTIONARY returning to England, he discovered that a vari- ety of finches he had collected on the Galapagos EPIC Islands had beaks that were subtly adapted to their different environments and food sources. Darwin later combined this idea with the obser- vation of how populations tend to overbreed and strain their resources. I mean, if there’s competi- tion for resources in an environment, then animals with useful traits would survive and pass those traits on to their offspring. Those who didn’t sur- 0:00–0:40 Hi, I’m John Green. Welcome to Crash Course Big vive long enough to reproduce would have their History. Today we’re going to be traversing the traits wiped out from the evolutionary tree: natural THE ULTIMATE EPIC evolutionary epic — the great story of magnificent selection. beasts, terrifying predators, quite a lot of extinc- tions, and countless varieties of evolutionary We talked some on Crash Course Big History about 1:36–2:12 forms. It’s the ultimate epic — millions upon mil- good science, and Darwin was a good scientist. He lions of species playing out a drama that has so far worked on his ideas for two decades, systemati- GOOD SCIENCE lasted 3.8 billion years with 99% of the actors hav- cally finding new evidence to support his case, and ing already left the stage forever. -

“Decreasing World Suck”

Dz dzǣ Fan Communities, Mechanisms of Translation, and Participatory Politics Neta Kligler-Vilenchik A Case Study Report Working Paper Media, Activism and Participatory Politics Project AnnenBerg School for Communication and Journalism University of Southern California June 24, 2013 Executive Summary This report describes the mechani sms of translation through which participatory culture communities extend PHPEHUV¶cultural connections toward civic and political outcomes. The report asks: What mechanisms do groups use to translate cultural interests into political outcomes? What are challenges and obstacles to this translation? May some mechanisms be more conducive towards some participatory political outcomes than others? The report addresses these questions through a comparison between two groups: the Harry Potter Alliance and the Nerdfighters. The Harry Potter Alliance is a civic organization with a strong online component which runs campaigns around human rights issues, often in partnership with other advocacy and nonprofit groups; its membership skews college age and above. Nerdfighters are an informal community formed around a YouTube vlog channel; many of the pDUWLFLSDQWVDUHKLJKVFKRRODJHXQLWHGE\DFRPPRQJRDORI³GHFUHDVLQJZRUOGVXFN.´ These two groups have substantial overlapping membership, yet they differ in their strengths and challenges in terms of forging participatory politics around shared cultural interests. The report discusses three mechanisms that enable such translation: 1. Tapping content worlds and communities ± Scaffolding the connections that group members have through their shared passions for popular culture texts and their relationships with each other toward the development of civic identities and political agendas. 2. Creative production ± Encouraging production and circulation of content, especially for political expression. 3. Informal discussion ± Creating and supporting spaces and opportunities for conversations about current events and political issues. -

Female Characters in John Green's Novels

Imagine me complexly: Female characters in John Green’s novels Ida Tamminen Master’s thesis English Philology Department of Modern Languages University of Helsinki May 2017 Tiedekunta/Osasto – Fakultet/Sektion – Faculty Laitos – Institution – Department Humanistinen tiedekunta Nykykielten laitos Tekijä – Författare – Author Ida Tamminen Työn nimi – Arbetets titel – Title Imagine me complexly: Female characters in John Green’s novels Oppiaine – Läroämne – Subject Englantilainen filologia Työn laji – Arbetets art – Level Aika – Datum – Month and Sivumäärä– Sidoantal – Number of pages Pro gradu year 16.05.2017 76 Tiivistelmä – Referat – Abstract Pro gradussani tarkastelen naishahmoja John Greenin kirjoissa Looking for Alaska, An Abundance of Katherines, Paper Towns ja The Fault in Our Stars. Tutkielmani tavoitteena on selvittää miten naishahmoja kuvataan Greenin kirjoissa ja miten se eroaa mieshahmojen kuvauksesta. Lisäksi pohdin mediarepresentaation tärkeyttä etenkin nuorille suunnatussa kirjallisuudessa sekä sitä, ovatko Greenin naishahmot autenttisen tuntuisia. Teoriataustana käytän teoksia hahmojentutkimuksen, feministisen kirjallisuusteorian, kerronnantutkimuksen ja stereotyyppientutkimuksen alueilta. Tutkimusmenetelmänäni on tekstin huolellinen lukeminen, eng. ’close reading’, teoria-aineistooni nojautuen. Aineistonani käytän Greenin kirjojen lisäksi hänen omia mielipiteitään, kommenttejaan ja vastauksiaan, joita hän on esittänyt lukuisissa blogeissaan. Pro graduni keskeisimpiä tuloksia on se, että naishahmot on esitetty eri tavalla -

Towards a Unified Theory Analysing Workplace Ideologies: Marxism And

Marxism and Racial Oppression: Towards a Unified Theory Charles Post (City University of New York) Half a century ago, the revival of the womens movementsecond wave feminismforced the revolutionary left and Marxist theory to revisit the Womens Question. As historical materialists in the 1960s and 1970s grappled with the relationship between capitalism, class and gender, two fundamental positions emerged. The dominant response was dual systems theory. Beginning with the historically correct observation that male domination predates the emergence of the capitalist mode of production, these theorists argued that contemporary gender oppression could only be comprehended as the result of the interaction of two separate systemsa patriarchal system of gender domination and the capitalist mode of production. The alternative approach emerged from the debates on domestic labor and the predominantly privatized character of the social reproduction of labor-power under capitalism. In 1979, Lise Vogel synthesized an alternative unitary approach that rooted gender oppression in the tensions between the increasingly socialized character of (most) commodity production and the essentially privatized character of the social reproduction of labor-power. Today, dual-systems theory has morphed into intersectionality where distinct systems of class, gender, sexuality and race interact to shape oppression, exploitation and identity. This paper attempts to begin the construction of an outline of a unified theory of race and capitalism. The paper begins by critically examining two Marxian approaches. On one side are those like Ellen Meiksins Wood who argued that capitalism is essentially color-blind and can reproduce itself without racial or gender oppression. On the other are those like David Roediger and Elizabeth Esch who argue that only an intersectional analysis can allow historical materialists to grasp the relationship of capitalism and racial oppression.