The Holocaust

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Holocaust : the Documentary Evidence / Introduction by Henry J

D 804 .3 H655 1993 ..v** \ ”>k^:>00'° * k5^-;:^C ’ * o4;^>>o° • ’>fe £%' ’5 %^S' w> «* O p N-4 ^ y° ^ ^ if. S' * * ‘/c*V • • •#• O' * ^V^A. f ° V0r*V, »■ ^^hrJ 0 ° "8f °^; ^ " ^Y> »<<■ °H° %>*,-’• o/V’m*' ( ^ »1 * °* •<> ■ 11 • 0Vvi » » !■„ V " o « % Jr % > » *"'• f ;M’t W ;• jfe*-. w 4»Yv4-W-r ' '\rs9 - ^ps^fc 1 v-v « ^ o f SI ° ^SJJV o J o cS^f) 2 IISII - ?%^ * .v W$M : <yj>A. * * A A, o WfyVS? =» _ 0 c^'Tn ft / /, , *> -X- V^W/.ov o e b' j . &? \v 'Mi.»> 'Sswr o, J?<v.v w lv4><k\NJ * ^ ^ . °o \V<<> x<P o* Sffli: "£? iiPli5 XT i^sm” TT - W"» w *<|E5»; •J.oJ%P/ y\ %^p»# j*\ °*Ww; 4?% « ^WmW^O . *S° * l>t-»^\V, ” * CTo4;^o° * * : • o°^4oo° • V'O « •: v .••gpaV. \* :f •: K:#i K •#;o K il|:>C :#• !&: V ; ", *> Q *•a- vS#^.//'n^L;V *y* >wT<^°x- *** *jt 1' , ,»*y co ' >n 9 v3 ^S'J°'%‘,“'" V’t'^X,,“°y°>*e,°'S,',n * • • C\,'“K°,45»,-*<>A^'” **^*. f°C 8 ^\W- A/.fef;^ tM; i\ ^ # # ^ *J0g§S 4'°* ft V4°/ rv j- ^ O >?'V 7!&l'ev ❖ ft r Oo ^4#^irJ> 1fS‘'^s3:i ^ O >P-4* ^ rf-^ *2^70^ -r ^ ^ ._ * \44\§s> u _ ^,§<!, <K 4 L< « ,»9vyv%s« »,°o,'*»„;,* 4*0 “» o°, 1.0, -r X*MvV/'Sl'" *>4v >X'°*°y'(• > /4>-' K ** <T ^ r 4TSS "oz Vv «r >j,'j‘ cpS'a" WMW » » ,©fi^ * c^’tw °,ww * <^v4 *1 3 V/fF'-k^k z “y^3ts.\N ^ <V'’ ^V> , '~^>S/ ji^ * »j, o a> ’Cf' Q ,7—-. -

The Obedience Alibi Milgram 'S Account of the Holocaust Reconsidered

David R. Mandel The Obedience Alibi Milgram 's Account of the Holocaust Reconsidered "Unable to defy the authority of the experimenter, [participantsj attribute all responsibility to him. It is the old story of 'just doing one's duty', that was heard time and again in the defence statement of the accused at Nuremberg. But it would be wrang to think of it as a thin alibi concocted for the occasion. Rather, it is a fundamental mode of thinking for a great many people once they are locked into a subordinate position in a structure of authority." {Milgram 1967, 6} Abstract: Stanley Milgram's work on obedience to authority is social psychology's most influential contribution to theorizing about Holocaust perpetration. The gist of Milgram's claims is that Holocaust perpetrators were just following orders out of a sense of obligation to their superiors. Milgram, however, never undertook a scholarly analysis of how his obedience experiments related to the Holocaust. The author first discusses the major theoretical limitations of Milgram's position and then examines the implications of Milgram's (oft-ignored) experimental manipula tions for Holocaust theorizing, contrasting a specific case of Holocaust perpetration by Reserve Police Battalion 101 of the German Order Police. lt is concluded that Milgram's empirical findings, in fact, do not support his position-one that essen tially constitutes an obedience alibi. The article ends with a discussion of some of the social dangers of the obedience alibi. 1. Nazi Germany's Solution to Their J ewish Question Like the pestilence-stricken community of Oran described in Camus's (1948) novel, The Plague, thousands ofEuropean Jewish communities were destroyed by the Nazi regime from 1933-45. -

Education with Testimonies, Vol.4

Education with Testimonies, Vol.4 Education with Testimonies, Vol.4 INTERACTIONS Explorations of Good Practice in Educational Work with Video Testimonies of Victims of National Socialism edited by Werner Dreier | Angelika Laumer | Moritz Wein Published by Werner Dreier | Angelika Laumer | Moritz Wein Editor in charge: Angelika Laumer Language editing: Jay Sivell Translation: Christopher Marsh (German to English), Will Firth (Russian to English), Jessica Ring (German to English) Design and layout: ruf.gestalten (Hedwig Ruf) Photo credits, cover: Videotaping testimonies in Jerusalem in 2009. Eyewitnesses: Felix Burian and Netty Burian, Ammnon Berthold Klein, Jehudith Hübner. The testimonies are available here: www.neue-heimat-israel.at, _erinnern.at_, Bregenz Photos: Albert Lichtblau ISBN: 978-3-9818556-2-3 (online version) ISBN: 978-3-9818556-1-6 (printed version) © Stiftung „Erinnerung, Verantwortung und Zukunft” (EVZ), Berlin 2018 All rights reserved. The work and its parts are protected by copyright. Any use in other than legally authorized cases requires the written approval of the EVZ Foundation. The authors retain the copyright of their texts. TABLE OF CONTENTS 11 Günter Saathoff Preface 17 Werner Dreier, Angelika Laumer, Moritz Wein Introduction CHAPTER 1 – DEVELOPING TESTIMONY COLLECTIONS 41 Stephen Naron Archives, Ethics and Influence: How the Fortunoff Video Archive‘s Methodology Shapes its Collection‘s Content 52 Albert Lichtblau Moving from Oral to Audiovisual History. Notes on Praxis 63 Sylvia Degen Translating Audiovisual Survivor Testimonies for Education: From Lost in Translation to Gained in Translation 76 Éva Kovács Testimonies in the Digital Age – New Challenges in Research, Academia and Archives CHAPTER 2 – TESTIMONIES IN MUSEUMS AND MEMORIAL SITES 93 Kinga Frojimovics, Éva Kovács Tracing Jewish Forced Labour in the Kaiserstadt – A Tainted Guided Tour in Vienna 104 Annemiek Gringold Voices in the Museum. -

What Do Students Know and Understand About the Holocaust? Evidence from English Secondary Schools

CENTRE FOR HOLOCAUST EDUCATION What do students know and understand about the Holocaust? Evidence from English secondary schools Stuart Foster, Alice Pettigrew, Andy Pearce, Rebecca Hale Centre for Holocaust Education Centre Adrian Burgess, Paul Salmons, Ruth-Anne Lenga Centre for Holocaust Education What do students know and understand about the Holocaust? What do students know and understand about the Holocaust? Evidence from English secondary schools Cover image: Photo by Olivia Hemingway, 2014 What do students know and understand about the Holocaust? Evidence from English secondary schools Stuart Foster Alice Pettigrew Andy Pearce Rebecca Hale Adrian Burgess Paul Salmons Ruth-Anne Lenga ISBN: 978-0-9933711-0-3 [email protected] British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A CIP record is available from the British Library All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism or review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permissions of the publisher. iii Contents About the UCL Centre for Holocaust Education iv Acknowledgements and authorship iv Glossary v Foreword by Sir Peter Bazalgette vi Foreword by Professor Yehuda Bauer viii Executive summary 1 Part I Introductions 5 1. Introduction 7 2. Methodology 23 Part II Conceptions and encounters 35 3. Collective conceptions of the Holocaust 37 4. Encountering representations of the Holocaust in classrooms and beyond 71 Part III Historical knowledge and understanding of the Holocaust 99 Preface 101 5. Who were the victims? 105 6. -

Clauberg's Eponym and Crimes Against Humanity

IMAJ • VOL 14 • deceMber 2012 FOCUS Clauberg’s Eponym and Crimes against Humanity Frederick Sweet PhD1 and Rita M. Csapó-Sweet EdD2 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, USA 2Department of Media Studies, University of Missouri-St. Louis, St. Louis, MO, USA discoverers. The eponym issue is less settled because the ABSTRACT: Scientific journals are ethically bound to cite Professor names had become part of medical literature [3-6]. Dr. Carl Clauberg’s Nazi medical crimes against humanity In 2007, Strous and Edelman [3] argued that eradicating whenever the eponym Clauberg is used. Modern articles Nazi doctor eponyms has become critical. They conceded that still publish the eponym citing only the rabbit bioassay used there might be arguments for preserving Nazi doctor eponyms in developing progesterone agonists or antagonists for in order to keep alive the memory of criminal medical behav- birth control. Clauberg’s Nazi career is traced to his having ior. Physicians need reminding how a few can darken their subjected thousands of Jewish women at the Ravensbruck profession by monstrously betraying medical ethics. Moreover, and Auschwitz-Birkenau death camps to cruel, murderous shockingly inhumane Nazi medical experiments associated sterilization experiments that are enthusiastically described with the perpetrators’ eponyms can help remind students of by incriminating letters (reproduced here) between him and lessons taught in medical ethics classes long after the classes the notorious Nazi Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler. The experiments were carried out in women’s block 10 in Auschwitz- have ended. Nevertheless, it was proposed [3]: Birkenau where Clauberg’s colleague Dr. -

Mauthausen-Gusen Concentration Camp System Varies Considerably from Source to Source

Mauthausen-Gusen concentrationCoordinates: 48°15camp′32″N 14°30′04″E From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Mauthausen Concentration Camp (known from the summer of 1940 as Mauthausen- Gusen Concentration Camp) grew to become a large group of Nazi concentration camps that was built around the villages of Mauthausen and Gusen in Upper Austria, roughly 20 kilometres (12 mi) east of the city of Linz. Initially a single camp at Mauthausen, it expanded over time to become one of the The Mauthausen parade ground – a view largest labour camp complexes in German- towards the main gate controlled Europe.[1][2] Apart from the four main sub-camps at Mauthausen and nearby Gusen, more than 50 sub-camps, located throughout Austria and southern Germany, used the inmates as slave labour. Several subordinate camps of the KZ Mauthausen complex included quarries, munitions factories, mines, arms factories and Me 262 fighter-plane assembly plants.[3] In January 1945, the camps, directed from the central office in Mauthausen, contained roughly 85,000 inmates.[4] The death toll remains unknown, although most sources place it between 122,766 and 320,000 for the entire complex. The camps formed one of the first massive concentration camp complexes in Nazi Germany, and were the last ones to be liberated by the Western Allies or the Soviet Union. The two main camps, Mauthausen and Gusen I, were also the only two camps in the whole of Europe to be labelled as "Grade III" camps, which meant that they were intended to be the toughest camps for the "Incorrigible Political -

The Truth of the Capture of Adolf Eichmann (Pdf)

6/28/2020 The Truth of the Capture of Adolf Eichmann » Mosaic THE TRUTH OF THE CAPTURE OF ADOLF EICHMANN https://mosaicmagazine.com/essay/history-ideas/2020/06/the-truth-of-the-capture-of-adolf-eichmann/ Sixty years ago, the infamous Nazi official was abducted in Argentina and brought to Israel. What really happened, what did Hollywood make up, and why? June 1, 2020 | Martin Kramer About the author: Martin Kramer teaches Middle Eastern history and served as founding president at Shalem College in Jerusalem, and is the Koret distinguished fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Listen to this essay: Adolf Eichmann’s Argentinian ID, under the alias Ricardo Klement, found on him the night of his abduction. Yad Vashem. THE MOSAIC MONTHLY ESSAY • EPISODE 2 June: The Truth of the Capture of Adolf Eichmann 1x 00:00|60:58 Sixty years ago last month, on the evening of May 23, 1960, the Israeli prime minister David Ben-Gurion made a brief but dramatic announcement to a hastily-summoned session of the Knesset in Jerusalem: A short time ago, Israeli security services found one of the greatest of the Nazi war criminals, Adolf Eichmann, who was responsible, together with the Nazi leaders, for what they called “the final solution” of the Jewish question, that is, the extermination of six million of the Jews of Europe. Eichmann is already under arrest in Israel and will shortly be placed on trial in Israel under the terms of the law for the trial of Nazis and their collaborators. In the cabinet meeting immediately preceding this announcement, Ben-Gurion’s ministers had expressed their astonishment and curiosity. -

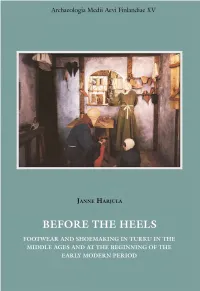

Footwear and Shoemaking in Turku in the Middle Ages and at the Beginning of the Early Modern Period

Janne Harjula Before the Heels Footwear and Shoemaking in Turku in the Middle Ages and at the Beginning of the Early Modern Period Archaeologia Medii Aevi Finlandiae XV Suomen keskiajan arkeologian seura – Sällskapet för medeltidsarkeologi i Finland Janne Harjula Before the Heels Footwear and Shoemaking in Turku in the Middle Ages and at the Beginning of the Early Modern Period Suomen keskiajan arkeologian seura Turku Editorial Board: Anders Andrén, Knut Drake, David Gaimster, Georg Haggrén, Markus Hiekkanen, Werner Meyer, Jussi-Pekka Taavitsainen and Kari Uotila Editor Janne Harjula Language revision Colette Gattoni Layout Jouko Pukkila Cover design Janne Harjula and Jouko Pukkila Published with the kind support of Emil Aaltonen Memorial Fund and Fingrid Plc Cover image Reconstruction of a medieval shoemaker’s workshop. Produced for an exhibition introducing the 15th and 16th centuries. Technical realization: Schweizerisches Waffeninstitut Grandson. Photograph: K. P. Petersen. © 1987 Museum für Vor- und Frühgeschichte SMPK Berlin. Back cover images Children’s shoes from excavations in Turku. Janne Harjula/Turku Provincial Museum. ISBN: ISSN: 1236-5882 Saarijärven Offset Oy Saarijärvi 2008 5 CONTENTS Preface 9 Introduction 11 Questions and the definition of the study 12 Research history 13 Material and methodology 17 PART I: FOOTWEAR 21 1. SHOE TYPES IN TURKU 21 1.1 One-piece shoes 22 1.1.1 The type definition and research history of one-piece shoes in Turku 22 1.1.2 The number and types of one-piece shoes 22 1.1.2.1 Cutting patterns -

Criminals with Doctorates: an SS Officer in the Killing Fields of Russia

1 Criminals with Doctorates An SS Officer in the Killing Fields of Russia, as Told by the Novelist Jonathan Littell Henry A. Lea University of Massachusetts-Amherst Lecture Delivered at the University of Vermont November 18, 2009 This is a report about the Holocaust novel The Kindly Ones which deals with events that were the subject of a war crimes trial in Nuremberg. By coincidence I was one of the courtroom interpreters at that trial; several defendants whose testimony I translated appear as major characters in Mr. Littell's novel. This is as much a personal report as an historical one. The purpose of this paper is to call attention to the murders committed by Nazi units in Russia in World War II. These crimes remain largely unknown to the general public. My reasons for combining a discussion of the actual trial with a critique of the novel are twofold: to highlight a work that, as far as I know, is the first extensive literary treatment of these events published in the West and to compare the author's account with what I witnessed at the trial. In the spring of 1947, an article in a Philadelphia newspaper reported that translators were needed at the Nuremberg Trials. I applied successfully and soon found myself in Nuremberg translating documents that were needed for the ongoing cases. After 2 passing a test for courtroom interpreters I was assigned to the so-called Einsatzgruppen Case. Einsatzgruppen is a jargon word denoting special task forces that were sent to Russia to kill Jews, Gypsies, so-called Asiatics, Communist officials and some mental patients. -

Holocaust and World War II Timeline 1933 1934 1935

Holocaust and World War II Timeline 1933 January 30 German President Paul von Hindenburg appoints Adolf Hitler Chancellor of Germany Feb. 27-28 German Reichstag (Parliament) mysteriously burns down, government treats it as an act of terrorism Feb. 28 Decree passed which suspends the civil rights granted by the German constitution March 4 Franklin Delano Roosevelt inaugurated President of the United States March 22 Dachau concentration camp opens as a prison camp for political dissidents March 23 Reichstag passes the Enabling Act, empowering Hitler to establish a dictatorship April 1 Nationwide Nazi organized boycott of Jewish shops and businesses April 7 Laws for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service bars Jews from holding civil service, university, and state positions April 26 Gestapo established May 10 Public burning of books written by Jews, political dissidents, and others July 14 The Nazi Party is declared the only legal party in Germany. Law on the Revocation of Naturalization stripping East European Jewish immigrants, as well as Roma (Gypsies), of German citizenship 1934 June 20 The SS (Schutzstaffel or Protection Squad), under Heinrich Himmler, is established as an independent organization. June 30 Night of the Long Knives – members of the Nazi party and police murdered members of the Nazi leadership, army and others on Hitler’s orders. Ernst Röhm, leader of the SA was killed. August 2 President von Hindenburg dies. Hitler proclaims himself Führer. Armed forces must now swear allegiance to him Oct. 7 Jehovah’s Witness congregations submit standardized letters to the government declaring their political neutrality Oct.-Nov. First major arrests of homosexuals throughout Germany Dec. -

Resistance in the Ghettos

Say 76 Resistance in the Ghettos Tim Say While some scholars like Raul Hilberg have argued that there was little resistance from Jews during the Holocaust, the large amount of evidence available has demonstrated that this is false, and that Jews resisted in many different ways. Specifically in the ghettos throughout Europe, resistance took many different forms which can be categorized as either active or passive resistance. The most well-known examples of resistance are the various uprisings, such as in the Warsaw ghetto, though it also includes other active forms such as raids to attack German supply lines or train stations. Active resistance was not common throughout the ghettos, however, as it created controversy because of the very real threat of reprisals from the Germans, who had no compunction about killing dozens of Jews in retaliation for one German death. This threat divided many ghettos about whether or not active resistance was the appropriate action to take. The concept of passive resistance was perhaps more important, as it was much more prevalent throughout the ghettos and affected the everyday lives of the majority of the inhabitants. It included life giving examples such as the smuggling of food, as well as more psychological examples such as religious education, or cultural activities like music and theatre. These types of examples are especially important because they specifically address the German strategy of demoralizing the inhabitants of the ghettos. Additionally, they serve to demonstrate that resistance was not only common throughout the ghettos, but was integral in maintaining the health and identity of the Jewish community in the face of the desperate circumstances. -

Jewish Behavior During the Holocaust

VICTIMS’ POLITICS: JEWISH BEHAVIOR DURING THE HOLOCAUST by Evgeny Finkel A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Political Science) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN–MADISON 2012 Date of final oral examination: 07/12/12 The dissertation is approved by the following members of the Final Oral Committee: Yoshiko M. Herrera, Associate Professor, Political Science Scott G. Gehlbach, Professor, Political Science Andrew Kydd, Associate Professor, Political Science Nadav G. Shelef, Assistant Professor, Political Science Scott Straus, Professor, International Studies © Copyright by Evgeny Finkel 2012 All Rights Reserved i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation could not have been written without the encouragement, support and help of many people to whom I am grateful and feel intellectually, personally, and emotionally indebted. Throughout the whole period of my graduate studies Yoshiko Herrera has been the advisor most comparativists can only dream of. Her endless enthusiasm for this project, razor- sharp comments, constant encouragement to think broadly, theoretically, and not to fear uncharted grounds were exactly what I needed. Nadav Shelef has been extremely generous with his time, support, advice, and encouragement since my first day in graduate school. I always knew that a couple of hours after I sent him a chapter, there would be a detailed, careful, thoughtful, constructive, and critical (when needed) reaction to it waiting in my inbox. This awareness has made the process of writing a dissertation much less frustrating then it could have been. In the future, if I am able to do for my students even a half of what Nadav has done for me, I will consider myself an excellent teacher and mentor.