A Recipe for Emigration: Grain Price Fluctuations and Italian Emigration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9. Notes and Index.Pdf

- NOTE rn NoI NOTES ,i I cccnt .rSarrlst i \ t:t tC. i l. cloes Preface l. J:rnres Joll, The Anarchisls,2nd etl , (C)ambridge, Nlass.: H:rn'artl llnivet'sin Press, 'i:tlike 19tt0), p viii. .r .rl istic: 2 Sinr:e the literature on this oeriod of soci:rlis( ernd cornrnunist intertrationalism is i.rlizccl immense, it is possible to rite onlr solne rcprL\r'ntJti\c titles here Julius BtaLnthal's ()eschir.hte der Internationale, 3 r'oirs (Flarlno\er: Dietz, l96l-1971 I has bccornc standarcl ' lllrl)l\ on a ccnturl of internationalisrn, though the emphasis is alrnostexclusivclr uporr politir:al . )|S [O :rnd not trade union intern:rtionalisrn. IIore sper:ifir:rllr, on the Setoncl Internatioral, sce Jarnes Joll, The Second InternatiormL, 1889-1911. rcr ed. (l-rtrrdon ancl Boston: r.hil)s, Routledge ancl Keean Paul, 197'1). On the International Federation of Trade flnions before ,11( )ln1C the rvar arrd on its post-rvar rerival. see Joh:rnn Sasst:nbach, I'inlundzuanzig Ja.lLre internationaLer Geuterksthaf tsbelDegung (Anrstcr(1arn: IrrtcrrraIionalcn C]cterlschaf tsbun- .Li aucl dcs, 1926), and Lervis Lonvin, Lobor and Inlernatiortalisrn (Ncl York: N'Iacrnillan, 1929). iltloIls, C)n the pcrst-war Labour and Socialist International, see John Ptice, Tlrc Intcrttational Labour Llouernent (London: Oxford l-iniversitl Press 19.15) On the so-callecl Trro-ancl- ;, lile, a-Half Internationzrl, scc Andr6 Donneur, Hi.stoire de I'L'nion des Pttrtis SetciaListes (tour I'Action InternationaLe (Lausanue: fl niversit6 de ClenEve, Institu t l-n ir crsi Lairc dcs FIaLrtes :;r otlet n -L,tudes Internat.ionales, 1967). -

The Life and Work of Frank Lloyd Wright

THE LIFE AND WORK OF FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT PART 4 Ages 42 (1909) to 47 (1914) In Italy and Wisconsin Wunderlich PhD website: http://users.etown.edu/w/wunderjt/ Architecture Portfolio 8/28/2018 PART 1: Frank Lloyd Wright Age 0-19 (1867-1886) PDF PPTX-w/audio MP4 YouTube Context: Post Civil War recession. Industrial Revolution. Farm life. Preacher/Musician-Father, Teacher-Mother. Mother’s large influential Unitarian family of Welsh farmers. Nature. Parent’s divorce. Architecture: Froebel schooling (e.g., blocks). Barns/farm-houses (PDF PPTX-w/audio MP4 YouTube). Organic Architecture roots. PART 2: Frank Lloyd Wright Age 20-33 (1887-1900) PDF PPTX-w/audio MP4 YouTube. Context: Rebuilding Chicago after the Great Fire. Wife Catherine and first five children. Architecture: Architects Joseph Silsbee and Louis Sullivan. Oak Park. Home & Studio. “Organic Architecture” begins. PART 3: Frank Lloyd Wright Age 34-41 (1901-1908) PDF PPTX-w/audio MP4 YouTube. Context: First Japan trip (PDF PPTX-w/audio MP4 YouTube). Arts & Crafts movements. Six children. Architecture: Prairie Style. Oak Park & River Forest, Unity Temple, Robie House, Larkin Building. PART 4: Frank Lloyd Wright Age 42-47 (1909-1914) PDF PPTX-w/audio MP4 YouTube THIS LECTURE Context: Runs off with Mistress. Lives in Italy (Page MP4 YouTube). Builds Taliesin on family farmland. Mistress murdered. Architecture: Wasmuth Portfolio published(Germany).Taliesin. Many operable windows for health & passive cooling. Sculptures. PART 5: Frank Lloyd Wright Age 48-62 (1915-1929) PDF PPTX-w/audio MP4 YouTube Context: WWI, Roaring 20’s. Short 2nd marriage. Lives 3 yrs in Japan, then California and Wisconsin. -

Criminal Prosecution and the Rationalization of Criminal Justice

-- Criminal Prosecution and The Rationalization of Criminal Pixstice Final Report William F. McDonald National Institute of Justice Fellow National Institute of Justice U.S. Department of Justice December, 1991 Acknowledgments This study was supported by Grant No. 88-IJ-CX-0026 from the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice to Georgetown University which made possible my participation in the NIJ Fellowship Program. It was also supported by my sabbatical grant from Georgetown University, which allowed me to conduct interviews and observations on the Italian justice system. And, it was supported by a travel grant from the Institute of Criminal Law and Procedure, Georgetown University Law Center. I would like to acknowledge my appreciation to the many people who made this entire undertaking the kind of intellectually and personally rewarding experience that one usually only dreams about. I hope that their generosity and support will be repaid to some extent by this report and by other contributions to the criminal justice literature which emerge from my thirteen months of uninterrupted exploration of the subject of this Fellowship. In particular I wish to thank James K. (Chips) Stewart, Joseph Kochanski, Bernard Auchter, Richard Stegman, Barbara Owen, Antonio Mura, Antonio Tanca, Paolo Tonini, Gordon Misner, and Samuel Dash and the anonymous NIJ reviewers who found my proposal for the Fellowship worth supporting. Points of view or opinions are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position of policies of the U.S. Department of Justice Georgetown University or any of the persons acknowledged above. -

The Kingdom of Italy: Unity Or Disparity, 1860-1945

The Kingdom of Italy: Unity or Disparity, 1860-1945 Part IIIb: The First Years of the Kingdom Governments of the Historic Left 1876-1900 Decline of the Right/Rise of the Left • Biggest issue dividing them had been Rome—now resolved • Emerging issues • Taxation, especially the macinato • Neglect of social issues • Free trade policies that hurt the South disproportionately • Limited suffrage • Piedmontization • Treatment of Garibaldi volunteers • Use of police against demonstrations The North-South divide • emerging issues more important to South • Many of Left leaders from South Elections of 1874 • Slim majority for Right Fall of Minghetti, March 1876 Appointment of a Left Prime Minister and the elections of November 1876 Agostino Depretis Benedetto Cairoli Francesco Crispi Antonio Starabba, Marchese di Rudinì Giovanni Giolitti Genl. Luigi Pelloux Prime Minister Dates in office Party/Parliament Key actions or events Agostino Depretis 25 March 1876 Left Coppino Law Lombardy 25 December 1877 Sonnino and Iacini inquiry into the problems of the South Railway construction continues with state aid 26 December 1877 Left Anarchist insurrection in Matese 24 March 1878 Benedetto Cairoli 24 March 1878 Left Attempted anarchist assassination of king Lombary 19 December 1878 Depretis 19 December 1878 Left 14 July 1879 Cairoli 14 July 1879 Left Costa founds Revolutionary Socialist Party of Romagna 25 November 1879 25 November 1879 Left 29 May 1881 Depretis 29 May 1881 Left Widened suffrage; first socialist elected 25 May 1883 Italy joins Austria-Hungary and Germany to create Triplice Use of trasformismo 25 May 1883 Left 30 March 1884 Final abolition of grist tax macinato 30 March 1884 Left First colonial venture into Assab and Massawa on Red Sea coast 29 June 1885 29 June 1885 Left Battle of Dogali debacle 4 April 1887 4 April 1887 Left 29 July 1887 Died in office Francesco Crispi 29 July 1887 Left 10-year tariff war with France begun Sicily 6 February 1891 Zanardelli penal code enacted; local govt. -

Family Tree Maker

Descendants of Luigi DeMarco (1) Casanova 1 Luigi DeMarco (1) Casanova b: in Italy . +Giuditta DeBettin m: in Italy ....... 2 Luigi DeMarco (2) Casanova b: 16 Aug 1875 in San Pietro di Cadore, Belluno, Italy d: 15 May 1961 in Wayne, New Jersey ........... +Maria DeLorenzo b: 05 Jun 1879 in Zoppe de Cadore, Italy m: 25 Dec 1904 in Clifton, New Jersey d: 1930 in Clifton, New Jersey ................ 3 Giuditta DeMarco b: 27 Oct 1905 in Clifton, New Jersey d: 05 Aug 1997 in Queens, New York .................... +Luigi Martin b: 14 Nov 1895 in Pordenone, Udine, Italy m: Nov 1928 d: 14 Jul 1984 in Queens, New York .......................... 4 Frank Louis Martin b: 23 Oct 1929 in Queens, New York .............................. +AnnaMaria Colizzo b: 18 Apr 1930 ................................... 5 Frank Louis Jr. Martin b: 02 May 1960 in Queens, New York ....................................... +Lisa Rose Forlenza m: 28 Dec 1991 ............................................. 6 Frank Louis III Martin b: 26 May 2000 in Manhassett, New York ............................................. 6 Julianna Rose Martin b: 20 Jan 2003 ............................................. 6 Jake Daniel Martin b: 31 Mar 2005 in Plainview, NY ................................... 5 Linda Ann Martin b: 27 Oct 1961 in Queens, New York ....................................... +Dennis Michael Cariello m: 23 Jul 1988 in Westbury, New York ............................................. 6 Lindsey Ann Cariello b: 02 May 1998 in Dunedin, Florida .......................... 4 James Placido Martin b: 08 Jul 1931 in Queens, New York .............................. +Marie Bryson ................................... 5 Claire Martin b: in Brooklyn, New York ....................................... +Joseph Crapa m: 12 Aug 1995 in Forrest Hills, New York ................................... 5 James Louis Martin b: 13 Jun 1969 .......................... 4 Estella Martin b: 17 Apr 1945 in Queens, New York ............................. -

Criminal Prosecution and the Rationalization of Criminal Justice Final Report

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. 1337?11 Criminal Prosecution and The Rationalization of Criminal Justice Final Report by William F. McDonald National Institute of Justice Fellow 133787 U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stated in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this 1_ I material has been gr~{l'bblic DOD.ain/NI~T u.s. Department of dustlce to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further reproduction oUlside of the NCJRS systern requires perrnis- sion of the • I owner. National Institute of Justice u.s. Department of Justice December, 1991 Acknowledgments This study was supported by Grant No. 88-IJ-CX-0026 from the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, u.s. Department of Justice to Georgetown University which made possible my participation in the NIJ Fellowship Program. It was also supported by my sabbatical grant from Georgetown University, which allowed me to conduct interviews and observations on the Italian justice system. And, it was supported by a travel' grant from the Institute of Criminal Law and Procedure, Georgetown University Law Center. I would like to acknowledge my appreciation to the many people who made this entire undertaking the kind of intellectually and personally rewarding experience that one usually only dreams about. I hope that their generosity and support will be repaid to some extent by this report and by other contributions to the criminal justice literature which emerge from my thirteen months of uninterrupted exploration of the subject of this Fellowship. -

Dysdercus Cingulatus

Prelims (F) Page i Monday, August 25, 2003 9:52 AM Biological Control of Insect Pests: Southeast Asian Prospects D.F. Waterhouse (ACIAR Consultant in Plant Protection) Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research Canberra 1998 Prelims (F) Page ii Monday, August 25, 2003 9:52 AM The Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) was established in June 1982 by an Act of the Australian Parliament. Its primary mandate is to help identify agricultural problems in developing countries and to commission collaborative research between Australian and developing country researchers in fields where Australia has special competence. Where trade names are used this constitutes neither endorsement of nor discrimination against any product by the Centre. ACIAR MONOGRAPH SERIES This peer-reviewed series contains the results of original research supported by ACIAR, or deemed relevant to ACIAR’s research objectives. The series is distributed internationally, with an emphasis on the Third World ©Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research GPO Box 1571, Canberra, ACT 2601. Waterhouse, D.F. 1998, Biological Control of Insect Pests: Southeast Asian Prospects. ACIAR Monograph No. 51, 548 pp + viii, 1 fig. 16 maps. ISBN 1 86320 221 8 Design and layout by Arawang Communication Group, Canberra Cover: Nezara viridula adult, egg rafts and hatching nymphs. Printed by Brown Prior Anderson, Melbourne ii Prelims (F) Page iii Monday, August 25, 2003 9:52 AM Contents Foreword vii 1 Abstract 1 2 Estimation of biological control -

French Spatial Inequalities in an Historical Perspective

Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne Ecole doctorale 465 - Economie Panthéon-Sorbonne Thèse présentée pour obtenir le titre de DOCTEUR en Economie French Spatial Inequalities in an Historical Perspective Florian Bonnet Soutenue publiquement le 11/12/2018 devant un jury composé de : Rapporteurs Ryan Edwards, Research Asociate Berkeley Population Center Farid Toubal, Professeur des Universités ENS Paris-Saclay Examinateurs Magali Barbieri, Chargée de Recherche INED & UC Berkeley Lionel Kesztenbaum, Chargé de Recherche INED & PSE Josselin Thuilliez, Chargé de Recherche CNRS & CES Directeur de thèse Hippolyte d’Albis, Directeur de Recherche CNRS & PjSE Paris Jourdan Sciences Economiques Abstract This Ph. D. thesis has a dual purpose. First, it presents the methods used to build two new historical databases relating to départements. The first database provides the departmental lifetables for the period 1901-2014. The second database provides the departmental distributions of income over the period 1960-2014. Second, this thesis presents the first works resulting from the joint use of these two databases and other statistics: they concern both the dynamics of spatial inequalities and some specific historical events. Thus, the analysis of the spatial distribution of the population since the middle of the 19th century allows to understand the dynamics induced by the rural exodus, but also by the new trends of today’s migrations. The analysis of mortality inequalities over the last 200 years shows that inequalities have fallen dramatically since the end of the 19th century, while the geography of excessmortality has changed. Finally, the analysis of spatial income inequalities reveals a continuous decline since the 1920s. This decline occurred only since 1950 if spatial inequalities are observed using asynthetic indicator of welfare, combining both mortality inequalities and income inequalities. -

Chapters Are Organised Thema� Cally to Cover: Wri� Ng and Solving Equa� Ons, Geometric Construc� On, Coordinates and Complex Numbers, A� Tudes to the Use

E Making up Numbers A History of Invention in Mathematics KKEHARD EKKEHARD KOPP Making up Numbers: A History of Inventi on in Mathemati cs off ers a detailed but K Making up Numbers accessible account of a wide range of mathema� cal ideas. Star� ng with elementary OPP concepts, it leads the reader towards aspects of current mathema� cal research. A History of Invention in Mathematics Ekkehard Kopp adopts a chronological framework to demonstrate that changes in our understanding of numbers have o� en relied on the breaking of long-held conven� ons, making way for new inven� ons that provide greater clarity and widen mathema� cal horizons. Viewed from this historical perspec� ve, mathema� cal abstrac� on emerges as neither mysterious nor immutable, but as a con� ngent, developing human ac� vity. Chapters are organised thema� cally to cover: wri� ng and solving equa� ons, geometric construc� on, coordinates and complex numbers, a� tudes to the use of ‘infi nity’ in mathema� cs, number systems, and evolving views of the role of M axioms. The narra� ve moves from Pythagorean insistence on posi� ve mul� ples to gradual acceptance of nega� ve, irra� onal and complex numbers as essen� al tools in quan� ta� ve analysis. AKING Making up Numbers will be of great interest to undergraduate and A-level students of mathema� cs, as well as secondary school teachers of the subject. By virtue of UP its detailed treatment of mathema� cal ideas, it will be of value to anyone seeking N to learn more about the development of the subject. -

Ceriani the Reception of Alberto Franchetti’S Works in the United States 271 Marialuisa Pepi Franchetti Attraverso I Documenti Del Gabinetto G.P

Alberto Franchetti. l’uomo, il compositore, l’artista Atti del convegno internazionale Reggio Emilia, 18-19 settembre 2010 a cura di Paolo Giorgi e Richard Erkens Alberto Franchetti. L’uomo, il compositore, l’artista il compositore, L’uomo, Franchetti. Alberto associazione per il musicista ALBERTO FRANCHETTI Alberto Franchetti l’uomo, il compositore, l’artista associazione per il musicista FRANCHETTI ALBERTO a cura di Paolo Giorgi e Richard Erkens € 30,00 LIM Libreria Musicale Italiana Questa pubblicazione è stata realizzata dall’Associazione per il musicista Alberto Franchetti, in collaborazione con il Comune di Regio Emilia / Biblioteca Panizzi, e con il sostegno di Stefano e Ileana Franchetti. Soci benemeriti dell’Associazione per il musicista Alberto Franchetti Famiglia Ponsi Stefano e Ileana Franchetti Fondazione I Teatri – Reggio Emilia Fondazione Pietro Manodori – Reggio Emilia Hotel Posta – Reggio Emilia Redazione, grafica e layout: Ugo Giani © 2015 Libreria Musicale Italiana srl, via di Arsina 296/f, 55100 Lucca [email protected] www.lim.it Tutti i diritti sono riservati. Nessuna parte di questa pubblicazione potrà essere riprodot- ta, archiviata in sistemi di ricerca e trasmessa in qualunque forma elettronica, meccani- ca, fotocopiata, registrata o altro senza il permesso dell’editore, dell’autore e del curatore. ISBN 978-88-7096-817-0 associazione per il musicista ALBERTO FRANCHETTI Alberto Franchetti l’uomo, il compositore, l’artista Atti del convegno internazionale Reggio Emilia, 18-19 settembre 2010 a cura di Paolo Giorgi e Richard Erkens Libreria Musicale Italiana Alla memoria di Elena Franchetti (1922-2009) Sommario Presentazione, Luca Vecchi xi Premessa, Stefano Maccarini Foscolo xiii Paolo Giorgi – Richard Erkens Introduzione xv Alberto Franchetti (1860-1942) l’uomo, il compositore, l’artista Parte I Dal sinfonista all’operista internazionale Antonio Rostagno Alberto Franchetti nel contesto del sinfonismo italiano di fine Ottocento 5 Emanuele d’Angelo Alla scuola di Boito. -

AGWS3-0729 02.Pdf (2.372Mb)

, S CURRENT NEWS BULLETINS The loose leaf service" Concerninr Suear 11 includes only such data as is of permanent value to the PALMER • suear industry; to supplement this, these unofficial news bulletins are issued for circulation amone members of the U. S. Surar Manufacturers' Association and covers subjects which are of temporary interest only, such as foreirn and domestic suear-beet seed, coal and other supplies, cost of beets. labor supDlY, proposed or enacted leeislation, testimony before Conrrcssional committees, etc., etc. Such comments and observations as these bulletins contain are to be considered merely as suee-estions for reflection and not as expressin2' the matured tbourbt of either the writer or of members of th e Association. Comments frequently are based upon unconfirmed newspaper reports and should be considered as bearing- tbe headline" Important if True. 1 1 -TRUMAN G, PALMER, (35) Washington, D, c. April 24, 1919, Gentlemen:- Herewith, I reproduce in full, a letter just received from Kuhn & Co,, sugar-beet seed growers, of Naarden, Holland. r visited their s E' ed laboratories in l'?HO and since have corresponded with them from time to time. The concern stands high, personally the Dudek van Heels are charming people and their laboratories and other equipment indicate careful and highly scientific work. In 1911 they outlined to me a plan somewhat on the lines of the letter herewith attached, but at that time. not enoug_~ interest was ~anifested by our people in the project to consid~r it seriously. s~ch information as reaches me, indicates that even though we still desired to depend upon Europe for this vital necessj_ty to the domestic sugar in dustry and to resume our former relations with a nation whtch has so grossly violated a11 established rules and laws of civilization, difficulty will be experienced in securing seed, and prices wi 11 be much higher than they were before the war. -

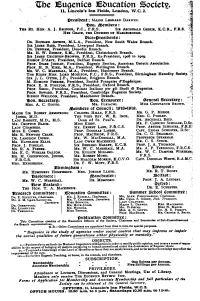

Ibe )Ugentcsebucation 5Octetb

ibe )ugentcs Ebucation 5octetb. 11, Lincoln's Inn Fields, London, W.C. 2.- OpeWbent: MAJOR LEONARD DARWIN. lbon. Menberse Tus RT. HON. A. 1. BALoui, P.C., F.R.S. Sit ARCHIBALD GEIIEm, K.C.B., F.R.S. HzR GRACE, THE DucHEss or MARLBOROUGH." VticesVreeizbents: DR. RICHARD ARTHUR, M.L.A., Presidchit, New South Wales Branch. SIR JAMEs BARR, President, Liverpool Branch. DR. BENHAM, President, Dunedin Branch. MR. H. W. BISHOP, S.M., President, Christchurch Branch. SIR JAMES CRICHTON.-BROwNE, F.R.S., Ex-President, I908 to I9o9. BIsHoP' D'ARcY, President, Belfast Branch. PROF. STARR JORDAN, President, Eugenic Section, American Genetic Association. PROF. H. B. KIRX, M.A., President, Wellington Branch. MR. W. C. MARSHALL, M.A., President, Haslemere Branch. THE RIGHT HON. LORD MOULTON, P.C., F.R.S., President, Birmingham Heredity Society. L SIR J. L. OTTER, J.P., President, Brighton Branch. M. EDMOND PERRIER, President, Soci&t6 Fran9aise d'Eug6nique. PROF. E. B. POULTON, F.R.S., President, Oxford Branch. PROF. SERGI, President, Comitato Italiano per gli Studi di Eugenica. PROF. SEWARD, F.R.S., President, Cambridge Eugenics Society. -e BIsHoP WELLDON, President, Manchester Branch. lbon. Secretar)2: lon. t;reasurel: 0eneraI Secretar2: _- MRS. A. C. GoTTo. - MDI LW --mv MISS CONSTANCE BROWN. Aftenibere of aounictl: 1918491fW9. MAJOR SIR ROBEzRT ARMSTRONG COLONEL, HILLS, F.R.S. MR. G. P. MUDGE. JONES, M.D. THE VERY- REv. W. R. INGE, MRS. G. PooLEY. LADY BARETT, M.D., M.S. Dean of St. Paul's. DR. ARCHDALL REID. MR. CROFTON --BLAcK. Miss KIRBY. MR. F. CANNING SCHILLER, D.SG.