A Psychobiographical Study of Theodore Robert Bundy: an Object

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 24/04/2017 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 24/04/2017 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars All Of Me - John Legend Blue Ain't Your Color - Keith Urban Shape of You - Ed Sheeran Jackson - Johnny Cash 24K Magic - Bruno Mars EXPLICIT Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton Piano Man - Billy Joel Unchained Melody - The Righteous Brothers Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond House Of The Rising Sun - The Animals I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Don't Stop Believing - Journey Black Velvet - Alannah Myles Sweet Home Alabama - Lynyrd Skynyrd Girl Crush - Little Big Town Before He Cheats - Carrie Underwood (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay - Otis Redding Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks My Way - Frank Sinatra Santeria - Sublime Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Turn The Page - Bob Seger Killing Me Softly - The Fugees Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Love on the Brain - Rihanna EXPLICIT He Stopped Loving Her Today - George Jones Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Wannabe - Spice Girls Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Can't Stop The Feeling - Trolls Love Shack - The B-52's Summer Nights - Grease Closer - The Chainsmokers I Will Survive - Gloria Gaynor Crazy - Patsy Cline Amarillo By Morning - George Strait A Whole New World - Aladdin Let It Go - Idina Menzel Wagon Wheel - Darius Rucker At Last - Etta James How Far I'll Go - Moana These Boots Are Made For Walkin' - Nancy Sinatra Strawberry Wine - Deana Carter My Girl - The Temptations Sweet Child O'Mine - Guns N' Roses Fly Me To The Moon -

Onderwijsrecensies Basisonderwijs 2015 - 1 4-6 Jaar Prentenboeken

Onderwijsrecensies basisonderwijs 2015 - 1 4-6 jaar Prentenboeken 2014-29-3450 Bon, Annemarie • Hiep hiep Haas! Niveau/leeftijd : AK Winkelprijs : € 14.95 Hiep hiep Haas! / Annemarie Bon ; met illustraties van Gertie Jaquet. - Amsterdam : Bijzonderheden : J1/J2/EX/ Moon, [2014]. - 26 ongenummerde pagina's : illustraties ; 30 cm Volgnummer : 44 / 173 ISBN 978-90-443-4521-6 Nog een nachtje slapen en dan is Haas jarig. Een verjaardagsfeest organiseren kost veel energie en tijd. Als Haas om acht uur naar bed gaat is hij best moe, maar slapen kan hij niet. Dan maar weer zijn bed uit! De hele nacht blijft hij doorgaan, waarbij brokken worden gemaakt en de taart verbrandt. Uitgeput valt hij ten slotte in slaap en wordt pas weer wakker als de feestgangers om zijn bed staan te zingen. Grappig, vlot leesbaar prentenboek met duidelijke tekst. De illustraties, in krijt stift en verf, zijn feestelijk gekleurd en in wisselende afmetingen. Ze zijn speels over de bladzijden verdeeld en sluiten naadloos aan op de situaties. Op elke pagina is een spinnetje verstopt en oplettende kleuters kunnen het tijdsverloop via tal van klokken volgen. Herkenbaar verhaal over de opwinding rondom een verjaardag. Vanaf ca. 4 jaar. Nelleke Hulscher-Meihuizen 2014-27-1933 Heruitgave Burton, Virginia Lee • Het huisje dat verhuisde *zie a.i.'s deze week voor nog vier prentenboeken uit de reeks 'Lemniscaat Het huisje dat verhuisde / Virginia Lee Burton ; vertaling [uit het Engels]: L.M. Niskos. Kroonjuweel'. - Vierde druk. - Rotterdam : Lemniscaat, 2014. - 44 ongenummerde pagina's : illustraties ; 24 × 26 cm. - (Lemniscaat Kroonjuweel). - Vertaling van: The little house. Niveau/leeftijd : AK - Boston : Houghton Mifflin, 1942. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 23 October 2012 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Sauerteig, Lutz (2012) 'Loss of innocence : Albert Moll, Sigmund Freud and the invention of childhood sexuality around 1900.', Medical history., 56 (Special issue 2). pp. 156-183. Further information on publisher's website: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/mdh.2011.31 Publisher's copyright statement: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk Med. Hist. (2012), vol. 56(2), pp. 156–183. c The Author 2012. Published by Cambridge University Press 2012 doi:10.1017/mdh.2011.31 Loss of Innocence: Albert Moll, Sigmund Freud and the Invention of Childhood Sexuality Around 1900 LUTZ D.H. SAUERTEIG∗ Centre for the History of Medicine and Disease, Wolfson Research Institute, Queen’s Campus, Durham University, Stockton-on-Tees TS17 6BH, UK Abstract: This paper analyses how, prior to the work of Sigmund Freud, an understanding of infant and childhood sexuality emerged during the nineteenth century. -

Rhetoric and Psychopathy: Linguistic Manipulation and Deceit in the Final Interview of Ted Bundy Rebecca Smithson (English Language and Linguistics)

Diffusion: the UCLan Journal of Undergraduate Research Volume 6 Issue 2 (December 2013) RHETORIC AND PSYCHOPATHY: LINGUISTIC MANIPULATION AND DECEIT IN THE FINAL INTERVIEW OF TED BUNDY REBECCA SMITHSON (ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LINGUISTICS) Abstract – Linguistic manipulation and deception are common aspects of interpersonal communication, which can prove problematic in situations where truthfulness is a matter of legal necessity. This study provides a linguistic analysis of the manipulative techniques used by serial killer Ted Bundy in the final interview in Florida before his execution in 1989. It begins with a brief account of related research and the context in which the Bundy interview took place, before analysing the language used by Bundy from two of the modes of persuasion identified by Aristotle: ethos and pathos. The aim of the study is to gain insight into how a psychopath uses language to manipulate evidence and to determine the extent to which theories of rhetoric are applicable to manipulation / deception as well as to persuasion in legal and political contexts. Keywords – Linguistic Manipulation, Psychopaths, Ted Bundy, Rhetoric, Ethos, Pathos. Introduction Linguistic methods of manipulation and deception are commonplace in everyday interpersonal communication. As Shuy points out, utilising language in a way which reflects favourably on oneself is expected in particular contexts, such as job interviews and political speeches (2002, ix). However, the boundary between what constitutes socially acceptable embellishment / understatement and manipulation or deceit is not always made clear (ibid.). In forensic contexts, where establishing truthfulness is a matter of legal necessity, this can prove extremely problematic, most particularly when ascriptions of guilt or innocence are partially or wholly dependent upon language-based evidence (such as witness testimony). -

Mary Klyap, Ph.D. Coordinator, Shared Accountability Howard County Public School System 410-313-6978 "Together, We Can"

From: Mary R. Levinsohn-Klyap To: Eva Yiu Subject: FW: IRB Proposal for Dissertation Date: Thursday, January 15, 2015 1:17:22 PM Attachments: IRB Synopsis - Donyall Dickey .doc Interview Questions for Disseratation - Edited.doc Dissertation Defend Date May 2015 7-27-14 .doc Thank you! Mary Klyap, Ph.D. Coordinator, Shared Accountability Howard County Public School System 410-313-6978 "Together, we can" From: Donyall D. Dickey [[email protected]] Sent: Thursday, January 15, 2015 11:59 AM To: Mary R. Levinsohn-Klyap Subject: IRB Proposal for Dissertation Mary, As we discussed, I am seeking permission to interview 8 African American males who despite being at risk for failure have succeeded/are succeeding academically as measured by performance on the Maryland School Assessment. I would only need to interview each boy (preferably former students of mine from Murray Hill Middle School. The interviews would be 30-45 minutes per student and could be done during or after school hours. The name of the school, the district, and the students will remain anonymous (I am required to keep it anonymous). Each participant/family will be compensated $200 for their participation in the form of an American Express Gift Card. Thank you for your consideration. My dissertation committee required me to reshape my study and I am so ready to walk across the state this summer. I have attached my IRB Proposal, APPROVED Interview Protocol and APPROVED Dissertation Proposal. Donyall (267) 331-6664 (F) www.educationalepiphany.com GEORGE WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY OFFICE OF HUMAN RESEARCH INSTITUTIONAL REVIEW BOARD [email protected] Phone: 202.994.2715 FAX: 202.994.0247 HUMANRESEARCH.GWU.EDU HUMAN RESEARCH STUDY SYNOPSIS (VERSION DATE:11/26/2014) TITLE: The African American Middle School Male Acheivement Gap and Peformance on State Assessments SPONSOR (FOR EXTERNAL FUNDING ONLY): IRB # (if already assigned, otherwise leave blank--will be assigned upon submission): STUDENT-LED PROJECT: YES NO PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR (MUST BE GWU FACULTY) LAST NAME:Tekleselassie FIRST NAME:Abebayehu DEGREE: Ph.D. -

Swept Under the Rug

Swept under the rug WSU student's remains found nine months after carpet reported missing from dorm By David Johnson of the Tribune Monday, February 9, 2009 Joyce LePage Jeff Olmstead is investigating the disappearence of WSU student Joyce LePage. Carpet taken from Stevens Hall at Washington State University was found in a deep ravine south of Pullman in 1972, containing the skeletal remains of Joyce LePage, nine months after she disappeared. PULLMAN - It started in a historic sorority house on the campus of Washington State University as a missing-carpet case. Nine months later, in the spring of 1972, the chunk of green shag carpet was found in a deep ravine 10 miles south of here. Inside were the skeletal remains of 21- year-old Joyce LePage, a WSU student. "There were things that were recovered there," retired WSU Police Sgt. Don Maupin recalls of LePage's remains being discovered in dense brush, "including remnants of the carpet, which came from Stevens Hall." Touted as the oldest continuously operating women's college dormitory in the western United States, Stevens Hall looks much like it did in July of 1971 - when LePage was known to illegally frequent the empty innards of the old building. "It was being renovated and she would go inside through an open window," Maupin recalls. "She would write letters. She would play the piano and she was staying in a couple of different rooms in there." LePage also had an apartment a few blocks away from Stevens Hall. And in the late afternoon of July 22, 1971, according to police reports, friends dropped her off at the apartment. -

TO: Aspen Historic Preservation Commission Frovf: Amy Guthrie, Historic Preservation Officer

{@s7 EMORAI\DUM TO: Aspen Historic Preservation Commission fROVf: Amy Guthrie, Historic Preservation Officer RE: Ute Cemetery National RegisterNomination DATE: July 11,2001 SUMMARY: Please review and be prepared to comment on the attached National Register nomination, just completed for Ute Cemetery. We received a grant to do this project. The author of the nomination is also under contract to complete a management plan for the cemetery. He, along with a small team of people experienced in historic landscapes and conservation of grave markers, will deliver their suggestions for better stewardship of the cemetery in September. The City plans to undertake any necessary restoration work in Spring 2002. USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form Page 4 UTE CEMETERY PITKIN COUNTY. COLORADO Name of Property CountY and State 1n Aannrnnhinol l)ata Acreage of Property 4.67 acres UTM References (Place additional UTM references on a continuation sheet) 2 1 13 343s00 4338400 - Zone Easting Northing %16- A-tns Nortffis z A Jee continuation sheet Verbal Boundary Description (Describe the borndaries of the property on a continuation sheet ) Bounda ry Justification (Explain wtry the boundaries were selected on a continuation sheet.) 1 1. Form Prepared Bv NAME/titIE RON SLADEK. PRESIDENT organization TATANKA HISTORICAL ASSOCIATES. lNC. date 28 JUNE 2001 street & number P.0. BOX 1909 telephone 970 / 229-9704 city or town stateg ziP code .80522 Additional Documentation Submit the fdloaing items with $e completed form: Continuation Sheets Maps A USGS map (7.5 or l5 minute series) indicating the property's location. A Sketch mapfor historic districts and properties having large acreage or numerous resources. -

The Life and Times of Penny Arcade. Matthew Hes Ridan Ames Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1996 "I Am Contemporary!": The Life and Times of Penny Arcade. Matthew heS ridan Ames Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Ames, Matthew Sheridan, ""I Am Contemporary!": The Life and Times of Penny Arcade." (1996). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6150. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6150 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

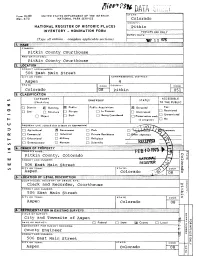

M COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF

/!?"' . P »!» n .--. - •" - I A ^UL. STATE: Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR (Rev. 6-72) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Colorado COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Pitkin INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY DATE (Type all entries complete applicable sections) UN 1 2 W5 COMMON: pitkin county Courthouse AND/OR HISTORIC: pitkin County courthouse STREET AND NUMBER: 506 East Main Street CITY OR TOWN: CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT: Aspen STATE Colorado 08 pitkin 051 BliMsfiiiiiiQi CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSH.P STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC Q District jg Building 89 Public Public Acquisition: (X) Occupied Yes: ,, .1 CH Restricted Q Site Q Structure D Private Q In Process Unoccupied r— i D • d— Unrestricted D Object D Both [~] Being Considered |-j p reservat|on w in progress ' — ' PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) [~1 Agricultural ps| Government | | Park Q Commercial CD Industrial ( | Private Residence C] Educational 1 1 Military [ | Religious Q Entertainment l~l Museum [~1 Scientific OWNER'S NAME-. ffffyws Pitkin county, Colorado Colorado STREET AND NUMBER: —NATIONAL 506 East Main Street CITY OR TOWN: STATE: Aspen Colorado m j~i 08 COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: Clerk and Recorder, Courthouse COUNTY: Pitkin STREET AND NUMBER: 506 East Main Street Cl TY OR TOWN: STATE Aspen Colorado 08 TITUE OF SURVEY: City and Townsite of Aspen DATE OF SURVEY: |~] Federal n State County Q Loca -J.A DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: County Engineer STREET AND NUMBER: 506 East Main Street CITY OR TOWN: STATE: Aspen Colorado 08 (Check One) Excellent Q Good Q Fair Deteriorated Q Roins Unexposed CONDITION (Check One) (Chock One) D Altered D Unaltered Q~] Moved Q Original Site DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL ("// Jcnoivn.) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Pitkin County acquired Lots K, L, M, N, and O, Block 92 of the Original Aspen Townsite in May of 1890. -

Smash Hits Volume 60

35p USA $1 75 March I9-April 1 1981 W I including MIND OFATOY RESPECTABLE STREE CAR TROUBLE TOYAH _ TALKING HEADS in colour FREEEZ/LINX BEGGAR &CO , <0$& Of A Toy Mar 19-Apr 1 1981 Vol. 3 No. 6 By Visage on Polydor Records My painted face is chipped and cracked My mind seems to fade too fast ^Pg?TF^U=iS Clutching straws, sinking slow Nothing less, nothing less A puppet's motion 's controlled by a string By a stranger I've never met A nod ofthe head and a pull of the thread on. Play it I Go again. Don't mind me. just work here. I don't know. Soon as a free I can't say no, can't say no flexi-disc comes along, does anyone want to know the poor old intro column? Oh, no. Know what they call me round here? Do you know? The flannel panel! The When a child throws down a toy (when child) humiliation, my dears, would be the finish of a more sensitive column. When I was new you wanted me (down me) Well, I can see you're busy so I won't waste your time. I don't suppose I can drag Now I'm old you no longer see you away from that blessed record long enough to interest you in the Ritchie (now see) me Blackmore Story or part one of our close up on the individual members of The Jam When a child throws down a toy (when toy) (and Mark Ellen worked so hard), never mind our survey of the British funk scene. -

Ethics Questions Raised by the Neuropsychiatric

REGULAR ARTICLE Ethics Questions Raised by the Neuropsychiatric, Neuropsychological, Educational, Developmental, and Family Characteristics of 18 Juveniles Awaiting Execution in Texas Dorothy Otnow Lewis, MD, Catherine A. Yeager, MA, Pamela Blake, MD, Barbara Bard, PhD, and Maren Strenziok, MS Eighteen males condemned to death in Texas for homicides committed prior to the defendants’ 18th birthdays received systematic psychiatric, neurologic, neuropsychological, and educational assessments, and all available medical, psychological, educational, social, and family data were reviewed. Six subjects began life with potentially compromised central nervous system (CNS) function (e.g., prematurity, respiratory distress syndrome). All but one experienced serious head traumas in childhood and adolescence. All subjects evaluated neurologically and neuropsychologically had signs of prefrontal cortical dysfunction. Neuropsychological testing was more sensitive to executive dysfunction than neurologic examination. Fifteen (83%) had signs, symptoms, and histories consistent with bipolar spectrum, schizoaffective spectrum, or hypomanic disorders. Two subjects were intellectually limited, and one suffered from parasomnias and dissociation. All but one came from extremely violent and/or abusive families in which mental illness was prevalent in multiple generations. Implications regarding the ethics involved in matters of culpability and mitigation are considered. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 32:408–29, 2004 The first well-documented case in America of execut- principle, the New Jersey Supreme Court, in the case ing a child antedates the American Revolution. In of State v. Aaron,5 overturned the death sentence of 1642, a 16-year-old boy, Thomas Graunger, was an 11-year-old slave convicted of murdering a hanged for the crime of bestiality, having sodomized younger child. -

University Microfilnns International 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete.