Population Changes in New England Seabirds Author(S): William H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kennebec Estuary Focus Areas of Statewide Ecological Significance Kennebec Estuary

Focus Areas of Statewide Ecological Significance: Kennebec Estuary Focus Areas of Statewide Ecological Significance Kennebec Estuary WHY IS THIS AREA SIGNIFICANT? The Kennebec Estuary Focus Area contains more than 20 percent of Maine’s tidal marshes, a significant percentage of Maine’s sandy beach and associated dune Biophysical Region habitats, and globally rare pitch pine • Central Maine Embayment woodland communities. More than two • Cacso Bay Coast dozen rare plant species inhabit the area’s diverse natural communities. Numerous imperiled species of animals have been documented in the Focus Area, and it contains some of the state’s best habitat for bald eagles. OPPORTUNITIES FOR CONSERVATION » Work with willing landowners to permanently protect remaining undeveloped areas. » Encourage town planners to improve approaches to development that may impact Focus Area functions. » Educate recreational users about the ecological and economic benefits provided by the Focus Area. » Monitor invasive plants to detect problems early. » Find ways to mitigate past and future contamination of the watershed. For more conservation opportunities, visit the Beginning with Habitat Online Toolbox: www.beginningwithhabitat.org/ toolbox/about_toolbox.html. Rare Animals Rare Plants Natural Communities Bald Eagle Lilaeopsis Estuary Bur-marigold Coastal Dune-marsh Ecosystem Spotted Turtle Mudwort Long-leaved Bluet Maritime Spruce–Fir Forest Harlequin Duck Dwarf Bulrush Estuary Monkeyflower Pitch Pine Dune Woodland Tidewater Mucket Marsh Bulrush Smooth Sandwort -

Nahant Reconnaissance Report

NAHANT RECONNAISSANCE REPORT ESSEX COUNTY LANDSCAPE INVENTORY MASSACHUSETTS HERITAGE LANDSCAPE INVENTORY PROGRAM Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation Essex National Heritage Commission PROJECT TEAM Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation Jessica Rowcroft, Preservation Planner Division of Planning and Engineering Essex National Heritage Commission Bill Steelman, Director of Heritage Preservation Project Consultants Shary Page Berg Gretchen G. Schuler Virginia Adams, PAL Local Project Coordinator Linda Pivacek Local Heritage Landscape Participants Debbie Aliff John Benson Mark Cullinan Dan deStefano Priscilla Fitch Jonathan Gilman Tom LeBlanc Michael Manning Bill Pivacek Linda Pivacek Emily Potts Octavia Randolph Edith Richardson Calantha Sears Lynne Spencer Julie Stoller Robert Wilson Bernard Yadoff May 2005 INTRODUCTION Essex County is known for its unusually rich and varied landscapes, which are represented in each of its 34 municipalities. Heritage landscapes are those places that are created by human interaction with the natural environment. They are dynamic and evolving; they reflect the history of the community and provide a sense of place; they show the natural ecology that influenced the land use in a community; and heritage landscapes often have scenic qualities. This wealth of landscapes is central to each community’s character; yet heritage landscapes are vulnerable and ever changing. For this reason it is important to take the first steps toward their preservation by identifying those landscapes that are particularly valued by the community – a favorite local farm, a distinctive neighborhood or mill village, a unique natural feature, an inland river corridor or the rocky coast. To this end, the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR) and the Essex National Heritage Commission (ENHC) have collaborated to bring the Heritage Landscape Inventory program (HLI) to communities in Essex County. -

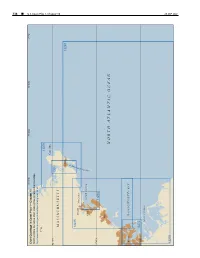

Grand Manan Channel – Southern Part NOAA Chart 13392

BookletChart™ Grand Manan Channel – Southern Part NOAA Chart 13392 A reduced-scale NOAA nautical chart for small boaters When possible, use the full-size NOAA chart for navigation. Published by the 33-foot unmarked rocky patch known as Flowers Rock, 3.9 miles west- northwestward of Machias Seal Island, the channel is free and has a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration good depth of water. The tidal current velocity is about 2.5 knots and National Ocean Service follows the general direction of the channel. Daily predictions are given Office of Coast Survey in the Tidal Current Tables under Bay of Fundy Entrance. Off West Quoddy Head, the currents set in and out of Quoddy Narrows, forming www.NauticalCharts.NOAA.gov strong rips. Sailing vessels should not approach West Quoddy Head too 888-990-NOAA closely with a light wind. North Atlantic Right Whales.–The Bay of Fundy is a feeding and nursery What are Nautical Charts? area for endangered North Atlantic right whales (peak season: July through October) and includes the Grand Manan Basin, a whale Nautical charts are a fundamental tool of marine navigation. They show conservation area designated by the Government of Canada. (See North water depths, obstructions, buoys, other aids to navigation, and much Atlantic Right Whales, chapter 3, for more information on right whales more. The information is shown in a way that promotes safe and and recommended measures to avoid collisions with whales.) efficient navigation. Chart carriage is mandatory on the commercial Southwest Head, the southern extremity of Grand Manan Island, is a ships that carry America’s commerce. -

Real Property Issues in the Marine Aquaculture Industry in New Brunswick

REAL PROPERTY ISSUES IN THE MARINE AQUACULTURE INDUSTRY IN NEW BRUNSWICK SUE NICHOLS IAN EDWARDS JIM DOBBIN KATALIN KOMJATHY SUE HANHAM October 2001 TECHNICAL REPORT NO. 208217 REAL PROPERTY ISSUES IN THE MARINE AQUACULTURE INDUSTRY IN NEW BRUNSWICK Sue Nichols Ian Edwards Jim Dobbin Katalin Komjathy Sue Hanham Department of Geodesy and Geomatics Engineering University ofNew Brunswick P.O. Box 4400 Fredericton, N.B. Canada E3B 5A3 October 2001 PREFACE In order to make our extensive series of technical reports more readily available, we have scanned the old master copies and produced electronic versions in Portable Document Format. The quality of the images varies depending on the quality of the originals. The images have not been converted to searchable text. PREFACE This report was prepared under contract for the New Brunswick Department of Fisheries and Aquaculture. The research was carried out in 1997 at the University of New Brunswick, Fredericton, Canada, under the leadership of Professor Sue Nichols. As with any copyrighted material, permission to reprint or quote extensively from this report must be received from the authors. The citation to this work should appear as follows: Nichols, S., I. Edwards, J. Dobbin, K. Komjathy, and S. Hanham (2001). Real Property Issues in the Marine Aquaculture Industry in New Brunswick. Final contract report for the New Brunswick Department of Fisheries and Aquaculture, by the Geographical Engineering Laboratory, Department of Geodesy and Geomatics Engineering Technical Report No. 208, University of New Brunswick, Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada, 102 pp. Real Property Issues in the Marine Aquaculture Industry in New Brunswick Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank for the Department of Fisheries and Aquaculture for recognising the need for this research and providing the funds. -

East Point History Text from Uniguide Audiotour

East Point History Text from UniGuide audiotour Last updated October 14, 2017 This is an official self-guided and streamable audio tour of East Point, Nahant. It highlights the natural, cultural, and military history of the site, as well as current research and education happening at Northeastern University’s Marine Science Center. Content was developed by the Northeastern University Marine Science Center with input from the Nahant Historical Society and Nahant SWIM Inc., as well as Nahant residents Gerry Butler and Linda Pivacek. 1. Stop 1 Welcome to East Point and the Northeastern University Marine Science Center. This site, which also includes property owned and managed by the Town of Nahant, boasts rich cultural and natural histories. We hope you will enjoy the tour Settlement in the Nahant area began about 10,000 years ago during the Paleo-Indian era. In 1614, the English explorer Captain John Smith reported: the “Mattahunts, two pleasant Iles of grouse, gardens and corn fields a league in the Sea from the Mayne.” Poquanum, a Sachem of Nahant, “sold” the island several times, beginning in 1630 with Thomas Dexter, now immortalized on the town seal. The geography of East Point includes one of the best examples of rocky intertidal habitat in the southern Gulf of Maine, and very likely the most-studied as well. This site is comprised of rocky headlands and lower areas that become exposed between high tide and low tide. This zone is easily identified by the many pools of seawater left behind as the water level drops during low tide. The unique conditions in these tidepools, and the prolific diversity of living organisms found there, are part of what interests scientists, as well as how this ecosystem will respond to warming and rising seas resulting from climate change. -

Historic Context Study of Waterfowl Hunting Camps and Related Properties Within Assateague Island National Seashore, Maryland and Virginia

Historic Context Study of Waterfowl Hunting Camps and Related Properties within Assateague Island National Seashore, Maryland and Virginia by Ralph E. Eshelman, Ph.D and Patricia A. Russell Eshelman & Associates July 21, 2004 For Assateague Island National Seashore National Park Service Department of Interior 7206 National Seashore Lane Berlin, Maryland 21811 i ii CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS…………………………………………………………. ii ABSTRACT………………………………………………………………………..iii INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………..1 Project background Clubs and lodges Definitions Regional context WATERFOWL HUNTING ON THE ATLANTIC ………………………………..7 Delaware North to New York Maryland Virginia North Carolina South to Georgia Assateague Island WATERFOWL HUNTING CLUBS AND LODGES……………………………..21 Land-Based Facilities Water-Based Facilities TYPICAL DAY AT A WATERFOWL HUNTING CLUB……………………….31 SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC ASPECTS OF WATERFOWL HUNTING CLUBS AND LODGES………………………………………………… 33 Owners Members Guests: The Rich and Famous Gender Guides Food Thrill of the Hunt Fraternal Comradeship Ethnicity of Support Staff Role in Conservation ASSATEGUE ISLAND WATERFOWL HUNTING CAMPS AND LODGES…………………………………………………………………..47 ASSOCIATED PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF ASSATEGUE ISLAND WATERFOWL HUNTING CLUBS AND LODGES………….49 iii INVENTORY OF RESOURCES…………………………………………………52 Bob-O-Del Gun Club Bunting’s Gunning Lodge Clements’ Beach House Clements’ Boat House Green Run Lodge High Winds Gun Club Hungerford’s Musser’s Peoples & Lynch Pope’s Island Gun Club Valentine’s CONCLUSION……………………………………………………………………72 REFERENCES CITED……………………………………………………………76 APPENDIX I ANNOTATED LIST OF GUN CLUBS AND LODGES IN MARYLAND AND VIRGINIA………………………………………90 APPENDIX II PROFESSIONAL TRAINING AND EXPERIENCE OF CONTEXT STUDY TEAM………………………………………………99 APPENDIX III CULTURAL LANDSCAPE FIELD SURVEY…………………………………100 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project benefited from numerous persons who assisted us in countless ways, shared knowledge, and otherwise made this study possible. -

Point Nepean Forts Conser Vation Management Plan

Point Nepean Forts Conservation Management Plan POINT NEPEAN FORTS CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN Parks Victoria July 2006 This document is based on the Conservation Plans for the Point Nepean National Park Fortifications (1990) and Gun Emplacement No. 1 (1988) prepared by the Historic Buildings Branch, Ministry Of Housing and Construction, reviewed and updated for currency at the time of creation of the new and expanded Point Nepean National Park in 2005. ii CONTEXT This Conservation Management Plan (CMP) for the Point Nepean Forts is one of three Conservation Management Plans for historic heritage that have been prepared and/or reviewed to support the Point Nepean National Park and Point Nepean Quarantine Station Management Plan, as shown below: Point Nepean National Park and Point Nepean Quarantine Station Draft Management Plan Point Nepean Forts South Channel Fort Point Nepean Quarantine Conservation Conservation Station Draft Conservation Management Plan Management Plan Management Plan The Conservation Management Plan establishes the historical significance of all the fortification structures centring on the Fort Nepean complex area, as well as Eagles Nest and Fort Pearce, develops conservation policies for the sites as a whole as well as their individual features, and provides detailed strategies and works specifications aimed at the ongoing preservation of those values into the future. The Conservation Management Plan for Point Nepean Forts supports the Point Nepean National Park and Point Nepean Quarantine Station Draft Management -

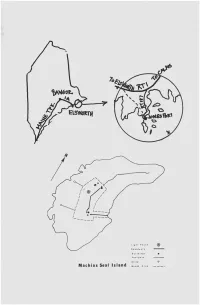

Machias Seal Island Mowad a R I MACHIAS SEAL ISLABD

Foet patK Bltn4 Machias Seal Island Mowad A r i MACHIAS SEAL ISLABD by Paula Butler, Belmont Machias Seal Island— the Contested Island*— has served as a sentinel at the South end of the Bay of Fundy slnce the estahlishment of a lighthouse in 1832. Before that time, this rock (barren except for a highland meadow in summer) vas a marinar's nightmare of sudden fog banks, high seas and hidden rocky shoals. The Harbour Seal, for whioh this island vas probably named, occurs only at a nearby shoal, North Rock. Although today's Journey is quite safe, trips to the island are cancelled vithout notice due to unexpected vind changes or a possible dangerous landing because of ground svells, strong cur- rents and surf. The meadov area of the island contains a variety of plant life: asters, vild parsleys, docks, grasses, sedges, and many other herbs. This island, like many others in the Machias Bay area, vas used for cattle and sheep grazing as vell as Limited farming. Some of these islands vere strategic in the naval maneuvers during the American Revolution. The first naval encounter of that var vas in Machias Bay vhen the villagers of Machias beached the British cutter Margareta. Most birders and photographers are attracted to Machias Seal Island to ob serve Common Puffins (Pratercula árctica) at cióse range. Common Puffins and Razorbills (Alca torda) seem to invite us not only to vatch them but to take delight in posing. Tvo blinds eire provided overlooking the rocky nesting area. The puffins arrive in late April and remain in the vater until they receive a mysterious signal; then, in one large flock, they settle into their nesting sites. -

2 Study Area

CA PDF Page 49 of 1038 Energy East Project Part B: Deterministic Modelling of the Ecological and Volume 24: Ecological and Human Health Risk Human Health Consequences of Marine Oil Spills Assessment for Oil Spills in the Marine Environment Section 2: Study Area 2 STUDY AREA The study area for the analysis of hypothetical crude oil spills for the proposed marine terminal is described in detail in Part A, Section 2 of the EHHRA. This section provides an overview. 2.1 Overview of Canaport Energy East Marine Terminal Operations and Expanded Shipping Operations The proposed marine terminal will be located on the western shore of the Bay of Fundy, southeast of the City of Saint John and southwest of Mispec Point, New Brunswick. The marine terminal is proposed to be located adjacent to the two existing Canaport marine facilities: a single buoy mooring (SBM or mono- buoy) for offloading crude oil to the Irving Canaport facility, and the Canaport LNG terminal for import and now recently licensed for export of liquefied natural gas (Figure 1-1). The marine terminal will include pile-supported trestles and breasting/mooring dolphins for two berths that can accommodate Aframax and Suezmax tankers (Berth 2), as well as VLCC tanker types (Berth 1), with capacities of 113,300 to 348,000 m3 (710,000 to 2.2 million barrels). The two berths will be constructed simultaneously. Oil will be pumped from shore via a trestle approximately 645 m long. Berths 1 and 2 will be interconnected by a trestle approximately 380 m long. The marine terminal is expected to receive approximately 281 tanker calls per year for shipping of crude oil products originating from western Canada. -

Seeing the Light: Report on Staffed Lighthouses in Newfoundland and Labrador and British Columbia

SEEING THE LIGHT: REPORT ON STAFFED LIGHTHOUSES IN NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR AND BRITISH COLUMBIA Report of the Standing Senate Committee on Fisheries and Oceans The Honourable Fabian Manning, Chair The Honourable Elizabeth Hubley, Deputy Chair October 2011 (first published in December 2010) For more information please contact us by email: [email protected] by phone: (613) 990-0088 toll-free: 1 800 267-7362 by mail: Senate Committee on Fisheries and Oceans The Senate of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, K1A 0A4 This report can be downloaded at: http://senate-senat.ca Ce rapport est également disponible en français. MEMBERSHIP The Honourable Fabian Manning, Chair The Honourable Elizabeth Hubley, Deputy Chair and The Honourable Senators: Ethel M. Cochrane Dennis Glen Patterson Rose-Marie Losier-Cool Rose-May Poirier Sandra M. Lovelace Nicholas Vivienne Poy Michael L. MacDonald Nancy Greene Raine Donald H. Oliver Charlie Watt Ex-officio members of the committee: The Honourable Senators James Cowan (or Claudette Tardif) Marjory LeBreton, P.C. (or Claude Carignan) Other Senators who have participated on this study: The Honourable Senators Andreychuk, Chaput, Dallaire, Downe, Marshall, Martin, Murray, P.C., Rompkey, P.C., Runciman, Nancy Ruth, Stewart Olsen and Zimmer. Parliamentary Information and Research Service, Library of Parliament: Claude Emery, Analyst Senate Committees Directorate: Danielle Labonté, Committee Clerk Louise Archambeault, Administrative Assistant ORDER OF REFERENCE Extract from the Journals of the Senate, Sunday, June -

CPB1 C10 WEB.Pdf

338 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 1, Chapter 10 Chapter 1, Pilot Coast U.S. 70°45'W 70°30'W 70°15'W 71°W Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 1—Chapter 10 NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml 71°W 13279 Cape Ann 42°40'N 13281 MASSACHUSETTS Gloucester 13267 R O B R A 13275 H Beverly R Manchester E T S E C SALEM SOUND U O Salem L G 42°30'N 13276 Lynn NORTH ATLANTIC OCEAN Boston MASSACHUSETTS BAY 42°20'N 13272 BOSTON HARBOR 26 SEP2021 13270 26 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 1, Chapter 10 ¢ 339 Cape Ann to Boston Harbor, Massachusetts (1) This chapter describes the Massachusetts coast along and 234 miles from New York. The entrance is marked on the northwestern shore of Massachusetts Bay from Cape its eastern side by Eastern Point Light. There is an outer Ann southwestward to but not including Boston Harbor. and inner harbor, the former having depths generally of The harbors of Gloucester, Manchester, Beverly, Salem, 18 to 52 feet and the latter, depths of 15 to 24 feet. Marblehead, Swampscott and Lynn are discussed as are (11) Gloucester Inner Harbor limits begin at a line most of the islands and dangers off the entrances to these between Black Rock Danger Daybeacon and Fort Point. harbors. (12) Gloucester is a city of great historical interest, the (2) first permanent settlement having been established in COLREGS Demarcation Lines 1623. The city limits cover the greater part of Cape Ann (3) The lines established for this part of the coast are and part of the mainland as far west as Magnolia Harbor. -

Historical Collections of the Topsfield Historical Society

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/historicalcollec26unse r. ; V:i , M 4 \ 1790. March, SALEM. Magazine, HOUSE, "Massachusetts TOWN AND the in HOUSE published COURT Hill, THE S. OF by VIEW engraving the From IVIUj THE HISTORICAL COLLECTIONS OF THE TOPSFIELD HISTORICAL SOCIETY VOLUME XXVI 1921 TOPSFIELD MASS. PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY 1921 GEORGE FRANCIS DOW Editor THE PERKINS PRESS MASS. CONTENTS VIEW OF THE COURT HOUSE, SALEM IN 1790 - - Frontispiece OFFICERS OF THE SOCIETY, 1920 iv ANNUAL REPORT OF THE SECRETARY FOR THE YEAR ENDING DEC. 31, 1920 V ANNUAL REPORT OF THE TREASURER FOR THE YEAR ENDING DEC. 31, 1920 vii - - ANNUAL REPORT ON THE BUILDING FUND - . viii ESSEX COUNTY IN THE MASSACHUSETTS BAY COLONY AS DE- SCRIBED BY EARLY TRAVELERS. COMMUNICATED BY GEORGE FRANCIS DOW (continued) 1 THE STORY OF A PEABODY HOUSE AND ITS NEIGHBORHOOD. BY CHARLES JOEL PEABODY 113 RECORDS OF MEETINGS OF THE CITIZENS AND COMMITTEE OF ARRANGEMENTS FOR THE CELEBRATION OF THE TWO HUNDREDTH ANNIVERSARY OF THE SETTLEMENT OF THE TOWN OF TOPSFIELD, 1850. COMMUNICATED BY LEONE P. WELCH 121 NEWSPAPER ITEMS RELATING TO TOPSFIELD, COPIED BY GEORGE FRANCIS DOW 128 TOPSFIELD VITAL STATISTICS, 1920 141 CHRONOLOGY OF EVENTS 1920, 144 BUILDINGS CONSTRUCTED, 1920 144 OFFICERS OF THE TOPSFIELD HISTORICAL SOCIETY 1920 President Charles Joel Peabody Vice-President Thomas Emerson Proctor Secretary and Treasurer George Francis Dow Curator Albert M. Dodge Board of Directors Charles Joel Peabody, ex-officio Thomas Emerson Proctor, ex-officio George Francis Dow, ex-officio W. Pitman Gould Isaac H. Sawyer Leone P. Welch Arthur H.