THE Official Magazine of the OCEANOGRAPHY SOCIETY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nahant Reconnaissance Report

NAHANT RECONNAISSANCE REPORT ESSEX COUNTY LANDSCAPE INVENTORY MASSACHUSETTS HERITAGE LANDSCAPE INVENTORY PROGRAM Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation Essex National Heritage Commission PROJECT TEAM Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation Jessica Rowcroft, Preservation Planner Division of Planning and Engineering Essex National Heritage Commission Bill Steelman, Director of Heritage Preservation Project Consultants Shary Page Berg Gretchen G. Schuler Virginia Adams, PAL Local Project Coordinator Linda Pivacek Local Heritage Landscape Participants Debbie Aliff John Benson Mark Cullinan Dan deStefano Priscilla Fitch Jonathan Gilman Tom LeBlanc Michael Manning Bill Pivacek Linda Pivacek Emily Potts Octavia Randolph Edith Richardson Calantha Sears Lynne Spencer Julie Stoller Robert Wilson Bernard Yadoff May 2005 INTRODUCTION Essex County is known for its unusually rich and varied landscapes, which are represented in each of its 34 municipalities. Heritage landscapes are those places that are created by human interaction with the natural environment. They are dynamic and evolving; they reflect the history of the community and provide a sense of place; they show the natural ecology that influenced the land use in a community; and heritage landscapes often have scenic qualities. This wealth of landscapes is central to each community’s character; yet heritage landscapes are vulnerable and ever changing. For this reason it is important to take the first steps toward their preservation by identifying those landscapes that are particularly valued by the community – a favorite local farm, a distinctive neighborhood or mill village, a unique natural feature, an inland river corridor or the rocky coast. To this end, the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR) and the Essex National Heritage Commission (ENHC) have collaborated to bring the Heritage Landscape Inventory program (HLI) to communities in Essex County. -

East Point History Text from Uniguide Audiotour

East Point History Text from UniGuide audiotour Last updated October 14, 2017 This is an official self-guided and streamable audio tour of East Point, Nahant. It highlights the natural, cultural, and military history of the site, as well as current research and education happening at Northeastern University’s Marine Science Center. Content was developed by the Northeastern University Marine Science Center with input from the Nahant Historical Society and Nahant SWIM Inc., as well as Nahant residents Gerry Butler and Linda Pivacek. 1. Stop 1 Welcome to East Point and the Northeastern University Marine Science Center. This site, which also includes property owned and managed by the Town of Nahant, boasts rich cultural and natural histories. We hope you will enjoy the tour Settlement in the Nahant area began about 10,000 years ago during the Paleo-Indian era. In 1614, the English explorer Captain John Smith reported: the “Mattahunts, two pleasant Iles of grouse, gardens and corn fields a league in the Sea from the Mayne.” Poquanum, a Sachem of Nahant, “sold” the island several times, beginning in 1630 with Thomas Dexter, now immortalized on the town seal. The geography of East Point includes one of the best examples of rocky intertidal habitat in the southern Gulf of Maine, and very likely the most-studied as well. This site is comprised of rocky headlands and lower areas that become exposed between high tide and low tide. This zone is easily identified by the many pools of seawater left behind as the water level drops during low tide. The unique conditions in these tidepools, and the prolific diversity of living organisms found there, are part of what interests scientists, as well as how this ecosystem will respond to warming and rising seas resulting from climate change. -

CPB1 C10 WEB.Pdf

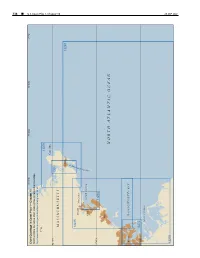

338 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 1, Chapter 10 Chapter 1, Pilot Coast U.S. 70°45'W 70°30'W 70°15'W 71°W Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 1—Chapter 10 NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml 71°W 13279 Cape Ann 42°40'N 13281 MASSACHUSETTS Gloucester 13267 R O B R A 13275 H Beverly R Manchester E T S E C SALEM SOUND U O Salem L G 42°30'N 13276 Lynn NORTH ATLANTIC OCEAN Boston MASSACHUSETTS BAY 42°20'N 13272 BOSTON HARBOR 26 SEP2021 13270 26 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 1, Chapter 10 ¢ 339 Cape Ann to Boston Harbor, Massachusetts (1) This chapter describes the Massachusetts coast along and 234 miles from New York. The entrance is marked on the northwestern shore of Massachusetts Bay from Cape its eastern side by Eastern Point Light. There is an outer Ann southwestward to but not including Boston Harbor. and inner harbor, the former having depths generally of The harbors of Gloucester, Manchester, Beverly, Salem, 18 to 52 feet and the latter, depths of 15 to 24 feet. Marblehead, Swampscott and Lynn are discussed as are (11) Gloucester Inner Harbor limits begin at a line most of the islands and dangers off the entrances to these between Black Rock Danger Daybeacon and Fort Point. harbors. (12) Gloucester is a city of great historical interest, the (2) first permanent settlement having been established in COLREGS Demarcation Lines 1623. The city limits cover the greater part of Cape Ann (3) The lines established for this part of the coast are and part of the mainland as far west as Magnolia Harbor. -

2016 GOMSWG Census Data Table

2016 Gulf of Maine Seabird Working Group Census Results Census Window: June 12-22 (peak of tern incubation) (Results from region-wide count period are reported here - refer to island synopsis or contact island staff for season totals) *not located in the Gulf of Maine or included in GOM totals numbers need to be verified ISLAND NAME DATE METHOD COTE ARTE ROST LETE LAGU FLEDGE/NEST N SD METHOD EGGS/NEST N SD OBSERVER NOVA SCOTIA 6/12 N 619 Julie McKnight North Brother 6/12 N 35 Julie McKnight South Brother Grassy Island 6/17 - 6/20 N 893 1.23 39 0.20 1, 3 Jen Rock Country Island (not in GOM) 6/17 - 6/20 N 581 1.18 28 0.22 1, 3 Jen Rock Season Total N 18 1.60 5 0.22 3 Jen Rock 2016 NS COAST TOTAL 619 50 2015 NS COAST TOTAL 687 0 35 0 0 2014 NS COAST TOTAL 651 44 38 0 0 2013 NS COAST TOTAL 596 50 38 0 0 2012 NS COAST TOTAL 574 50 34 0 0 2011 NS COAST TOTAL 631 60 38 0 0 2010 NS COAST TOTAL 632 54 38 0 0 * Data for The Brothers is reported as total count, with 38 roseates. 2009 NS COAST TOTAL 473 42 42 0 0 2008 NS COAST TOTAL 527 28 55 0 0 NEW BRUNSWICK ISLAND NAME DATE METHOD COTE ARTE ROST LETE LAGU FLEDGE/NEST N SD METHOD EGGS/NEST N SD OBSERVER Machias Seal Season Total NP 175 0.55 (ARTE only) 54 (ARTE only) 2,3 1.52 (ARTE only)4 (ARTE on 0.60 Stefanie Collar 2016 NB COAST TOTAL A tern census was not conducted this year, but it is estimated that there were up to 175 attempted nests island-wide, with a 2015 NB COAST TOTAL 9 141 0 0 0 probable species distribution of 94% ARTE and 6% COTE, similar to last year. -

Beverly Gloucester

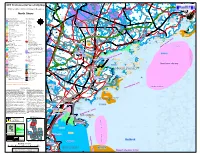

, "! k o W PINTAIL ro W S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S + S S S S S S S B POND THOMPSON "! e f W FOX i W MOUNTAIN ew ESSEX l ISLAND Þ VINEYARD Softshell clam A S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S!S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S 0 W S S S S S S S S S S MILL S S S S S S S B PINE HILL 0"! W POND R CRAFT HILL "! A ISLAND RIVERVIEW D , +0 W STRANGMAN S "! "! "! POND W T W S S S S S S S S S TOPSFIS SES S SLS SDS SÞR S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S SUNSET S S S S S S S !E SAGAMORE HILL GLOUCESTER R E HILL I T O H V R W S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S ILS S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S TURF MEADOW S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S SE S ive L SOUTH ESSEX S Ipswich R r E RAILCUT HILL R RIVERVIEW LANDING F k N i o , O DEP Environmental Sensitivity Map s COLT CANDLEWOOD EVELETH HILL ro S h "! S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S B S S S S S S S S S S Softshell clam S S S SB S S S B e A roo ISLAND SAVIN if B k w OAK ISLAND BUNKER le Þ W TURHKEY AMILHTILL ON A ! W MEADOWS S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S ISSLANDS S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S SWS S S S S S S S S S S S S W 0 E "! , ESSEX FALLS S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S -

Destruction Island Light, Washington

National Wildlife Refuge System Lighthouses More than two dozen lighthouses stand on U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service land managed by national wildlife refuges. Another half-dozen are often associated with a refuge but are not on U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service land. All can be seen from the outside; the inside of some is open to limited public visitation. Check with individual refuges for details. Most websites listed are unofficial, non-U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service sites. Pacific and Pacific Southwest Regions: Owned by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Daniel K. Inouye Kilauea Point Lighthouse Kilauea Point National Wildlife Refuge, Hawaii. http://www.fws.gov/nwrs/threecolumn.aspx?id=2147549718 http://www.lighthousefriends.com/light.asp?ID=139 Destruction Island Lighthouse Quillayute Needles National Wildlife Refuge, Washington. http://www.lighthousefriends.com/light.asp?ID=118 New Dungeness Lighthouse Dungeness National Wildlife Refuge System, Washington. http://www.fws.gov/refuge/Dungeness/visit/visitor_activities.html http://newdungenesslighthouse.com/ Farallon Island Lighthouse Farallon National Wildlife Refuge, California. http://www.lighthousefriends.com/light.asp?ID=100 Smith Island Lighthouse Washington Maritime National Wildlife Refuge Complex, Washington. [Archaeological site; structures collapsed and fell into sea] http://www.lighthousedigest.com/Digest/database/uniquelighthouse.cfm?value=1617 Not U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service-owned but Often Associated With a Refuge Tillamook Rock Lighthouse, Oregon http://www.lighthousefriends.com/light.asp?ID=135 Cape Meares Lighthouse, Oregon http://www.capemeareslighthouse.org/ Southwest Region: Owned by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Matagorda Lighthouse Aransas National Wildlife Refuge, Texas http://www.matagordalighthouse.com/ http://www.fws.gov/refuge/Aransas/about/matagorda.html Midwest Region: Owned by U.S. -

U.S. Lighthouse Society Participating Passport Stamp Locations Last Updated: June, 2021

U.S. Lighthouse Society Participating Passport Stamp Locations Last Updated: June, 2021 For complete information about a specific location see: https://uslhs.org/fun/passport-club. Visit their websites or call for current times and days of opening to insure that a stamp will be available. Some stamps are available by mail. See complete listings for locations offering this option and mail requirements. ALABAMA (3) CALIFORNIA FLORIDA HAWAII MAINE Fort Morgan Museum Table Bluff Tower Carysfort Reef McGregor Point Halfway Rock Middle Bay Trinidad Head Cedar Keys Nawiliwili Harbor Hendricks Head Sand Island Trinidad Head Memorial Crooked River Heron Neck ILLINOIS (2) Egmont Key Indian Island ALASKA (2) CONNECTICUT (20) Grosse Point Faro Blanco Isle au Haut Cape Decision Avery Point Metropolis Hope Light Fowey Rocks Kittery Hist. & Naval Museum Guard Island Black Rock Harbor Garden Key/Fort Jefferson INDIANA (2) Ladies Delight Brant Point Replica CALIFORNIA (40) Gasparilla Is. (Pt Boca Grande) Michigan City E Pier Libby Island Faulkner’s Island Alcatraz Gilbert’s Bar House of Refuge Old Michigan City Little River Five Mile Point Anacapa Island Hillsboro Inlet Lubec Channel Great Captain Island KENTUCKY (1) Angel Island Jupiter Inlet Machias Seal Island Green’s Ledge Louisville LSS Point Blunt Key West Maine Lighthouse Museum Lynde Point Point Knox Loggerhead LOUISIANA (6) Maine Maritime Museum Morgan Point Point Stuart Pacific Reef Lake Pontchartrain Basin Mark Island (Deer Is Thorofare) New London Harbor Ano Nuevo Pensacola Maritime Museum Marshall Point New London Ledge Battery Point Ponce De Leon Inlet New Canal Matinicus Rock Peck’s Ledge Cape Mendocino Port Boca Grande Rear Range Port Ponchartrain Monhegan Island Penfield Reef Carquinez Strait Rebecca Shoal Sabine Pass Moose Peak Saybrook BW East Brother Island Sand Key Southwest Reef (Berwick) Mount Desert Rock Sheffield Island Fort Point Sanibel Island Tchefuncte River Narraguagus Southwest Ledge Humbolt Bay Museum Sombrero Key Nash Island Stamford Harbor MAINE (71) Long Beach Harbor (Robot) St. -

A Springtime Exploration of Essex County's Coastal Islands, With

bo33-1:BO32-1.qxd 6/2/2011 6:26 AM Page 12 A Springtime Exploration of Essex County’s Coastal Islands, with Notes on Their Historical Use by Colonially Nesting Birds Jim Berry For over thirty years I have lived on the North Shore of Massachusetts without a boat and have long wondered what colonially nesting birds, in what numbers, have nested on the many islands along the Essex County coast. All I knew was that large gulls and cormorants nest on some of them, that terns used to nest on them, and that herons have used at least three of them, but beyond that I didn’t know many details. In 2004 I got a chance to learn more when I found out that my friends Mary Capkanis and Dave Peterson had acquired a boat, and that Mary had obtained a pilot’s license. Both are longtime birders, and both have experience surveying waterbird colonies in various parts of the U.S. Finally, I had the means to do some island- hopping with friends who were serious about surveying for nesting birds. We made three outings, on May 12, May 14, and May 31. Linda Pivacek accompanied us on the third trip. We were unable to get out in June and of course needed more trips, later in the nesting season, to complete even a preliminary census. But in those three days we visited (with very few landings) most of the 30+ islands between Rockport and Nahant that are large enough to support nesting birds. I had three goals for these trips: (1) to see where gulls and cormorants are nesting and in roughly what numbers, and whether terns still nest on any of the islands; (2) to find out whether herons are currently nesting on any islands other than Kettle, off Manchester; and (3) to look for evidence of nesting by other species, such as Common Eiders (Somateria mollissima), which have increased dramatically as nesters in Boston Harbor, and Great Cormorants (Phalacrocorax carbo), Black Guillemots (Cepphus grylle), and American Oystercatchers (Haematopus palliatus), for which there are no documented nesting records in Essex County. -

Fitz Henry Lane's Series Paintings of Brace's Rock: Meaning and Technique

Fitz Henry Lane’s Series Paintings of Brace’s Rock: Meaning and Technique FITZ HENRY LANE’S SERIES PAINTINGS OF BRACE’S ROCK: MEANING AND TECHNIQUE A report concerning the relationship of Lane’s painting series, Brace’s Rock Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, MA (CAM) National Gallery of Art, Washington DC (NGA) Terra Foundation for American Art, Chicago (TFAA) By H. Travers Newton, Jr., Consultant, Painting Conservation Studio, Cleveland Museum of Art Based on collaborative research with Marcia Steele, Chief Conservator, Cleveland Museum of Art Prepared for Elizabeth Kennedy, Curator of Collection, edited by Peter John Brownlee, Associate Curator, with the assistance of Naomi H. Slipp, Curatorial Intern, Terra Foundation for American Art April, 2010 ©2010 H. Travers Newton, Jr. 1 Table of Contents Project Introduction and Summary, 3 Part One: Review of the Literature I. Historical Background of Lane’s Images of Brace’s Rock, 4 II. Thematic Inspirations, Interpretations and Precedents: 1. Shipwrecks, 6 2. Nineteenth-Century Panorama Drawings and Paintings in the United States, 12 3. Influence of Thomas Doughty’s Nahant Beach Series, 14 4. Influence of Thomas Chambers, 16 5. Possible European Influences: Dutch Landscapes, 17 6. British Influences: John Ruskin and the Depiction of Rock Formations, 17 7. German and Danish Influences: Caspar David Friedrich and Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg, 20 Part Two: New Conservation Research on the Brace’s Rock Series, 21 III. Comparison of National Gallery of Art and Cape Ann Museum Versions of Brace’s Rock 1. Relationship of the Field Sketch to the Paintings: The Setting, 22 2. Absence of Reflections in Lane’s Drawings, 24 3. -

Table 1. Results of the 1994-95 Massachusetts Coastal Colonial

Table 1. Results of the 1994-95 Massachusetts Coastal Colonial Waterbird Inventory showing estimated numbers of pairs for all species at all colonies located in the coastal zone. An asterisk (*) indicates "count not taken." Data compiled by B.G. Blodget, Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife. COLONY SPECIES NO. OF PAIRS CENSUS REPORTING NUMBER COLONY NAME, TOWN CODE 1994 1995 METHOD1 AUTHORITY 324007.0 Woodbridge I., Newburyport COTE 65 62 ACG FWS 324007.1 Blackwater R. Group, Salisbury 0 0 TTOR 324007.2 Chaces I., Newbury COTE 14 0 ACG FWS HEGU 0 1 NCG FWS 324008.0 Plum I. R. Group, Newbury COTE 34 30 NCG FWS 324009.0 Parker R. Group, Newbury COTE 10 15 NCG FWS 324009.1 Plum I. Beach, Newbury-Rowley-Ip LETE 32 19 NCG FWS 324010.0 Roger I., Ipswich COTE 6 2 ACB ECG 324010.1 Stage I.-Cross Hill F., Ipswich * 0 FWS 324010.2 Bagwell I., Ipswich COTE 8 8 ACB ECG 324010.3 Rowley Salt Marshes, Rowley COTE 3 2 ACB ECG 324010.4 Lord's I., Ipswich COTE 25 20 ACB ECG 324010.5 Ipswich Salt Marshes, Ipswich COTE 13 13 ACB ECG 324011.0 Crane Beach, Ipswich LETE 30 75 NCG TTOR 324012.0 Tenpound I., Gloucester HEGU 75 * NCG DFW GBBG 70 * NCG DFW 324013.0 Norman's Woe, Gloucester DCCO 199 * NCG DFW HEGU 76 * NCG DFW TABLE 1... 2 COLONY SPECIES NO. OF PAIRS CENSUS REPORTING NUMBER COLONY NAME, TOWN CODE 1994 1995 METHOD AUTHORITY GBBG 4 * NCG DFW 324014.0 Kettle I., Gloucester GREG 42 * NCG DFW SNEG 207 * NCG DFW LBHE 6 * NCG DFW BCNH 7 * NCG DFW GLIB 35 * NCG DFW HEGU 388 * NCG DFW GBBG 146 * NCG DFW 324015.0 Graves I., Manchester HEGU 97 * NCG DFW GBBG 74 * NCG DFW 324016.0 Great Egg Rock, Manchester DCCO 124 * NCB DFW GBBG 2 * NCB DFW 324017.0 Dry Salvages, Rockport DCCO * 19 NCG DFW 324018.0 Straitsmouth I., Rockport HEGU 23 * NCG MAS GBBG 143 * NCG MAS 324019.0 Thacher I., Rockport BCNH 1 1 NCG DFW GLIB 0 1 AEG DFW HEGU 1,185 1,359 NCG FWS TABLE 1.. -

U.S. Coast Guard Historian's Office

U.S. Coast Guard Historian’s Office Preserving Our History For Future Generations Historic Light Station Information MASSACHUSETTS Note: Much of the following historical information and lists of keepers was provided through the courtesy of Jeremy D'Entremont and his website on New England lighthouses. ANNISQUAM HARBOR LIGHT CAPE ANN, MASSACHUSETTS; WIGWAM POINT/IPSWICH BAY; WEST OF ROCKPORT, MASSACHUSETTS Station Established: 1801 Year Current/Last Tower(s) First Lit: 1897 Operational? YES Automated? YES 1974 Deactivated: n/a Foundation Materials: STONE Construction Materials: BRICK Tower Shape: CYLINDRICAL ATTACHED TO GARAGE Height: 45-feet Markings/Pattern: WHITE W/BLACK LANTERN Characteristics: White flash every 7.5 seconds Relationship to Other Structure: ATTACHED Original Lens: FIFTH ORDER, FRESNEL Foghorn: Automated Historical Information: * 1801: Annisquam is the oldest of four lighthouses to guard Gloucester peninsula. The keeper’s house, built in 1801 continues to house Coast Guard families. Rudyard Kipling lived there while writing "Captain’s Courageous" – a great literary tribute to American sailors. * 1974: The 4th order Fresnel lens and foghorn were automated. Page 1 of 75 U.S. Coast Guard Historian’s Office Preserving Our History For Future Generations BAKERS ISLAND LIGHT Lighthouse Name: Baker’s Island Location: Baker’s Island/Salem Harbor Approach Station Established: 1791 Year Current/Last Tower(s) First Lit: 1821 Operational? Yes Automated? Yes, 1972 Deactivated: n/a Foundation Materials: Granite Construction Materials: Granite and concrete Tower Shape: Conical Markings/Pattern: White Relationship to Other Structure: Separate Original Lens: Fourth Order, Fresnel Historical Information: * In 1791 a day marker was established on Baker’s Island. It was replaced by twin light atop the keeper’s dwelling at each end in 1798. -

Annual Report of the Board of Harbor

* UMASS/AMHERST MASS. P.D. BlEDbb DEflS n31 fi f^yZ2^^ c.-*?c^^^»-^ 'T\ '1 mimmnn documents GOLLECIiON MiT2lS80 UnivGrsity of IVlassachusetts Depository Copy PUBLIC DOCUMENT .... .... No. 11. ANISTUAL REPORT Board of Haebor and Land Commissioners For the Year 1894 BOSTON : WRIGHT & POTTER PRINTING CO., STATE PRINTERS, 18 Post Office Square. 1895. Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2011 with funding from Boston Library Consortium IVIember Libraries http://www.archive.org/details/annualreportofbo1894boar ; fi^omin0n(xrcaltlj of ^assacktsctts. REPORT. To the Honorable the Senate and House of Bejiresentatives of the Com- monwealth of Massachusetts. The Board of Harbor and Land Commissioners, pursuant to the provisions of law, respectfully submits its annual re- port for the year 1894. The last report terminated with the 30th of November ; this report covers a period of twelve months from that date. Hearings and Inspections. The Board has held one hundred and sixty-three formal sessions during the year, and has given one hundred and thirty-one hearings. One hundred and nine applications for licenses for structures and for privileges in tide waters and great ponds have been passed upon ; of these applications, one hundred and eight were granted and one was refused. One formal hearing was given at North Falmouth, and the others in the office of the Board in Boston and in the State House. During the year the commissioners have personally in- spected the proposed location of a boat house, to be built in Sandy Pond in Lincoln ; the proposed location of a wharf, to be built by the town of Marblehead in Marble- head harbor ; Slate wharf in Boston ; the wharf of Linus M.