Fitz Henry Lane's Series Paintings of Brace's Rock: Meaning and Technique

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thomas Cole Thomas Cole Was Recognized As the “Father

Thomas Cole Thomas Cole was recognized as the “father of the Hudson River School of painting and hence one of the figures most directly involved in the development of a native tradition of American art...” He was “considered by his contemporaries the leading landscape painter in America...” Thomas Cole was born on February 1, 1801, in Lancashire, England. He was seventh of eight children and the only son of James and Mary Cole. His father was a woolen manufacturer who fell on hard times. Because of this, they moved to a nearby town where Thomas was apprenticed as a calico designer and where he learned the art of engraving. He especially enjoyed walking in the countryside with his youngest sister, playing the flute, and composing poetry. He was an avid reader and became interested in the natural beauties of the North American states. Thomas’ father caught his son’s enthusiasm. He moved his family to Philadelphia where he began business as a dry goods merchant. Thomas took up the trade of wood engraving. The family was soon moved again. This time to Steubenville, Ohio, but Thomas remained in Philadelphia. Not long afterwards, he sailed to St. Eustatius in the West Indies where he made sketches of what to him was nature in a grand form of wonder and beauty. A few months later, he returned to the US and joined his father in Ohio. There he helped his father by drawing and designing patterns for wallpaper. A book offered to him by a German portrait painter gave him information on design, composition, and color. -

Nahant Reconnaissance Report

NAHANT RECONNAISSANCE REPORT ESSEX COUNTY LANDSCAPE INVENTORY MASSACHUSETTS HERITAGE LANDSCAPE INVENTORY PROGRAM Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation Essex National Heritage Commission PROJECT TEAM Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation Jessica Rowcroft, Preservation Planner Division of Planning and Engineering Essex National Heritage Commission Bill Steelman, Director of Heritage Preservation Project Consultants Shary Page Berg Gretchen G. Schuler Virginia Adams, PAL Local Project Coordinator Linda Pivacek Local Heritage Landscape Participants Debbie Aliff John Benson Mark Cullinan Dan deStefano Priscilla Fitch Jonathan Gilman Tom LeBlanc Michael Manning Bill Pivacek Linda Pivacek Emily Potts Octavia Randolph Edith Richardson Calantha Sears Lynne Spencer Julie Stoller Robert Wilson Bernard Yadoff May 2005 INTRODUCTION Essex County is known for its unusually rich and varied landscapes, which are represented in each of its 34 municipalities. Heritage landscapes are those places that are created by human interaction with the natural environment. They are dynamic and evolving; they reflect the history of the community and provide a sense of place; they show the natural ecology that influenced the land use in a community; and heritage landscapes often have scenic qualities. This wealth of landscapes is central to each community’s character; yet heritage landscapes are vulnerable and ever changing. For this reason it is important to take the first steps toward their preservation by identifying those landscapes that are particularly valued by the community – a favorite local farm, a distinctive neighborhood or mill village, a unique natural feature, an inland river corridor or the rocky coast. To this end, the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR) and the Essex National Heritage Commission (ENHC) have collaborated to bring the Heritage Landscape Inventory program (HLI) to communities in Essex County. -

The Hudson River School

Art, Artists and Nature: The Hudson River School The landscape paintings created by the 19 th century artist known as the Hudson River School celebrate the majestic beauty of the American wilderness. Students will learn about the elements of art, early 19 th century American culture, the creative process, environmental concerns and the connections to the birth of American literature. New York State Standards: Elementary, Intermediate, and Commencement The Visual Arts – Standards 1, 2, 3, 4 Social Studies – Standards 1, 3 ELA – Standards 1, 3, 4 BRIEF HISTORY By the mid-nineteenth century, the United States was no longer the vast, wild frontier it had been just one hundred years earlier. Cities and industries determined where the wilderness would remain, and a clear shift in feeling toward the American wilderness was increasingly ruled by a new found reverence and longing for the undisturbed land. At the same time, European influences - including the European Romantic Movement - continued to shape much of American thought, along with other influences that were distinctly and uniquely American. The traditions of American Indians and their relationship with nature became a recognizable part of this distinctly American Romanticism. American writers put words to this new romantic view of nature in their works, further influencing the evolution of American thought about the natural world. It found means of expression not only in literature, but in the visual arts as well. A focus on the beauty of the wilderness became the passion for many artists, the most notable came to be known as the Hudson River School Artists. The Hudson River School was a group of painters, who between 1820s and the late nineteenth century, established the first true tradition of landscape painting in the United States. -

The Pear-Shaped Salvator Mundi Things Have Gone Very Badly Pear-Shaped for the Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi

AiA Art News-service The pear-shaped Salvator Mundi Things have gone very badly pear-shaped for the Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi. It took thirteen years to discover from whom and where the now much-restored painting had been bought in 2005. And it has now taken a full year for admission to emerge that the most expensive painting in the world dare not show its face; that this painting has been in hiding since sold at Christie’s, New York, on 15 November 2017 for $450 million. Further, key supporters of the picture are now falling out and moves may be afoot to condemn the restoration in order to protect the controversial Leonardo ascription. Above, Fig. 1: the Salvator Mundi in 2008 when part-restored and about to be taken by one of the dealer-owners, Robert Simon (featured) to the National Gallery, London, for a confidential viewing by a select group of Leonardo experts. Above, Fig. 2: The Salvator Mundi, as it appeared when sold at Christie’s, New York, on 15 November 2017. THE SECOND SALVATOR MUNDI MYSTERY The New York arts blogger Lee Rosenbaum (aka CultureGrrl) has performed great service by “Joining the many reporters who have tried to learn about the painting’s current status”. Rosenbaum lodged a pile of awkwardly direct inquiries; gained a remarkably frank and detailed response from the Salvator Mundi’s restorer, Dianne Dwyer Modestini; and drew a thunderous collection of non-disclosures from everyone else. A full year after the most expensive painting in the world was sold, no one will say where it has been/is or when, if ever, it might next be seen. -

A NEWSLETTER from the CAPE ANN VERNAL POND TEAM Winter/Spring 2015 Website: Email: [email protected]

A NEWSLETTER from the CAPE ANN VERNAL POND TEAM Winter/Spring 2015 Website: www.capeannvernalpond.org Email: [email protected] THE CAVPT IS A HOPELESSLY NON-PROFIT VOLUNTEER ORGANIZATION DEDICATED TO VERNAL POND CONSERVATION AND EDUCATION SINCE 1990. This year we celebrate our 25th anniversary. With the help, inspiration, and commitment of a lot of people we’ve come a long way! Before we get into our own history we have to give a nod to Roger Ward Babson (1875-1967) who had the foresight to • The Pole’s Hill ladies - led by Nan Andrew, Virginia Dench, preserve the watershed land in the center of Cape Ann known as and Dina Enos were inspirational as a small group of people who Dogtown. His love of Dogtown began as a young boy when he organized to preserve an important piece of land; the Vernal Pond would accompany his grandfather on Sunday afternoon walks to Team was inspired by their success. Hey, you really can make a difference! bring rock salt to the cows that grazed there. After his grandfa- ther passed away he continued the • CAVPT received its first grant ($200 from tradition with his father, Nathaniel. New England Herpetological Society) for When Nathaniel died in 1927 Roger film and developing to aid in certifying pools. began purchasing tracts of land to preserve Dogtown. In all he purchased • By 1995 we certified our first pools, the 1,150 acres, which he donated to cluster of nine ponds on Nugent Stretch at the City of Gloucester in 1932, to be old Rockport Road (where the vernal pond used as a park and watershed. -

The Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art Receives the Extraordinary American Art Collection of Theodore E

March 9, 2021 CONTACT: FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Emily Sujka Cell: (407) 907-4021 Office: (407) 645-5311, ext. 109 [email protected] The Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art Receives the Extraordinary American Art Collection of Theodore E. Stebbins Jr. and Susan Cragg Stebbins Note to Editors: Attached is a high-resolution image of Theodore E. Stebbins Jr. and Susan Cragg Stebbins. Images of several paintings in the gift are available via this Dropbox link: https://www.dropbox.com/sh/7d3r2vyp4nyftmi/AABg2el2ZCP180SIEX2GTcFTa?dl=0. WINTER PARK, FL—Theodore E. Stebbins Jr. and Susan Cragg Stebbins have given their outstanding collection of American art to The Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art in Winter Park, Florida. The couple have made their gift in honor of Mrs. Stebbins’s parents, Evelyn and Henry Cragg, longtime residents of Winter Park. Mr. Cragg was a member of the Charles Homer Morse Foundation board of trustees from its founding in 1976 until his death in 1988. It is impossible to think about American art scholarship, museum culture, and collecting without the name Theodore Stebbins coming to mind. Stebbins has had an illustrious career as a professor of art history and as curator at the Yale University Art Gallery (1968–77), the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (1977–2000), and the Harvard Art Museums (2001–14). Many of Stebbins’s former students occupy positions of importance throughout the art world. Among his numerous publications are his broad survey of American works on paper, American Master Drawings and Watercolors: A History of Works on Paper from Colonial Times to the Present (1976), and his definitive works on American painter Martin Johnson Heade (1819–1904) including the Life and Work of Martin Johnson Heade (2000). -

Art-Related Archival Materials in the Chicago Area

ART-RELATED ARCHIVAL MATERIALS IN THE CHICAGO AREA Betty Blum Archives of American Art American Art-Portrait Gallery Building Smithsonian Institution 8th and G Streets, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20560 1991 TRUSTEES Chairman Emeritus Richard A. Manoogian Mrs. Otto L. Spaeth Mrs. Meyer P. Potamkin Mrs. Richard Roob President Mrs. John N. Rosekrans, Jr. Richard J. Schwartz Alan E. Schwartz A. Alfred Taubman Vice-Presidents John Wilmerding Mrs. Keith S. Wellin R. Frederick Woolworth Mrs. Robert F. Shapiro Max N. Berry HONORARY TRUSTEES Dr. Irving R. Burton Treasurer Howard W. Lipman Mrs. Abbott K. Schlain Russell Lynes Mrs. William L. Richards Secretary to the Board Mrs. Dana M. Raymond FOUNDING TRUSTEES Lawrence A. Fleischman honorary Officers Edgar P. Richardson (deceased) Mrs. Francis de Marneffe Mrs. Edsel B. Ford (deceased) Miss Julienne M. Michel EX-OFFICIO TRUSTEES Members Robert McCormick Adams Tom L. Freudenheim Charles Blitzer Marc J. Pachter Eli Broad Gerald E. Buck ARCHIVES STAFF Ms. Gabriella de Ferrari Gilbert S. Edelson Richard J. Wattenmaker, Director Mrs. Ahmet M. Ertegun Susan Hamilton, Deputy Director Mrs. Arthur A. Feder James B. Byers, Assistant Director for Miles Q. Fiterman Archival Programs Mrs. Daniel Fraad Elizabeth S. Kirwin, Southeast Regional Mrs. Eugenio Garza Laguera Collector Hugh Halff, Jr. Arthur J. Breton, Curator of Manuscripts John K. Howat Judith E. Throm, Reference Archivist Dr. Helen Jessup Robert F. Brown, New England Regional Mrs. Dwight M. Kendall Center Gilbert H. Kinney Judith A. Gustafson, Midwest -

Lackawanna Valley

MAN and the NATURAL WORLD: ROMANTICISM (Nineteenth-Century American Landscape Painting) NINETEENTH-CENTURY AMERICAN LANDSCAPE PAINTING Online Links: Thomas Cole – Wikipedia Hudson River School – Wikipedia Frederic Edwin Church – Wikipedia Cole's Oxbow – Smarthistory Cole's Oxbow (Video) – Smarthistory Church's Niagara and Heart of the Andes - Smarthistory Thomas Cole. The Oxbow (View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm), 1836, oil on canvas Thomas Cole (1801-1848) was one of the first great professional landscape painters in the United States. Cole emigrated from England at age 17 and by 1820 was working as an itinerant portrait painter. With the help of a patron, he traveled to Europe between 1829 and 1832, and upon his return to the United States he settled in New York and became a successful landscape painter. He frequently worked from observation when making sketches for his paintings. In fact, his self-portrait is tucked into the foreground of The Oxbow, where he stands turning back to look at us while pausing from his work. He is executing an oil sketch on a portable easel, but like most landscape painters of his generation, he produced his large finished works in the studio during the winter months. Cole painted this work in the mid- 1830s for exhibition at the National Academy of Design in New York. He considered it one of his “view” paintings because it represents a specific place and time. Although most of his other view paintings were small, this one is monumentally large, probably because it was created for exhibition at the National Academy. -

East Point History Text from Uniguide Audiotour

East Point History Text from UniGuide audiotour Last updated October 14, 2017 This is an official self-guided and streamable audio tour of East Point, Nahant. It highlights the natural, cultural, and military history of the site, as well as current research and education happening at Northeastern University’s Marine Science Center. Content was developed by the Northeastern University Marine Science Center with input from the Nahant Historical Society and Nahant SWIM Inc., as well as Nahant residents Gerry Butler and Linda Pivacek. 1. Stop 1 Welcome to East Point and the Northeastern University Marine Science Center. This site, which also includes property owned and managed by the Town of Nahant, boasts rich cultural and natural histories. We hope you will enjoy the tour Settlement in the Nahant area began about 10,000 years ago during the Paleo-Indian era. In 1614, the English explorer Captain John Smith reported: the “Mattahunts, two pleasant Iles of grouse, gardens and corn fields a league in the Sea from the Mayne.” Poquanum, a Sachem of Nahant, “sold” the island several times, beginning in 1630 with Thomas Dexter, now immortalized on the town seal. The geography of East Point includes one of the best examples of rocky intertidal habitat in the southern Gulf of Maine, and very likely the most-studied as well. This site is comprised of rocky headlands and lower areas that become exposed between high tide and low tide. This zone is easily identified by the many pools of seawater left behind as the water level drops during low tide. The unique conditions in these tidepools, and the prolific diversity of living organisms found there, are part of what interests scientists, as well as how this ecosystem will respond to warming and rising seas resulting from climate change. -

NINETEENTH CENTURY AMERICAN PAINTINGS at BOWDOIN COLLEGE Digitized by the Internet Archive

V NINETEENTH CENTURY^ AMERIGAN PAINTINGS AT BOWDOIN COLLEGE NINETEENTH CENTURY AMERICAN PAINTINGS AT BOWDOIN COLLEGE Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/nineteenthcenturOObowd_0 NINETEENTH CENTURY AMERICAN PAINTINGS AT BOWDOIN COLLEGE BOWDOIN COLLEGE MUSEUM OF ART 1974 Copyright 1974 by The President and Trustees of Bowdoin College This Project is Supported by a Grant from The National Endowment for The Arts in Washington, D.C. A Federal Agency Catalogue Designed by David Berreth Printed by The Brunswick Publishing Co. Brunswick, Maine FOREWORD This catalogue and the exhibition Nineteenth Century American Paintings at Bowdoin College begin a new chapter in the development of the Bow- doin College Museum of Art. For many years, the Colonial and Federal portraits have hung in the Bowdoin Gallery as a permanent exhibition. It is now time to recognize that nineteenth century American art has come into its own. Thus, the Walker Gallery, named in honor of the donor of the Museum building in 1892, will house the permanent exhi- bition of nineteenth century American art; a fitting tribute to the Misses Walker, whose collection forms the basis of the nineteenth century works at the College. When renovations are complete, the Bowdoin and Boyd Galleries will be refurbished to house permanent installations similar to the Walker Gal- lery's. During the renovations, the nineteenth century collection will tour in various other museiniis before it takes its permanent home. My special thanks and congratulations go to David S. Berreth, who developed the original idea for the exhibition to its present conclusion. His talent for exhibition installation and ability to organize catalogue materials will be apparent to all. -

March 1978 CAA Newsletter

Volume 3, Number I March 1978 CAA awards 1978 annual meeting report Awards for excellence in art historical schol The high note and the low note of the 1978 arship and criticism and in the teaching of annual meeting were sounded back-to-back: studio arts and art history were presented at the high note on Friday evening, the Con the Convocation ceremonies of the 66th An vocation Address by Shennan E. Lee, a stun nual Meeting of the College Art Association, ning defense of the pursuit of excellence and held in the Grace Rainey Rogers Auditorium an attack upon anti-elitist demagoguery and of the Metropolitan Museum of Art on Friday the obliteration of the essential boundaries evening, January 27, 1978. between the realm of art and the realm of The Association's newest award (estab commerce by those with both the training and lished last year), for Distinguished Teaching the responsibility to know better. Too good to of Art History, was presented to Ellen John paraphrase, so we've culled some excerpts (see son, Professor Emeritus of Art and Honorary p. 3). Curator of Modem Art at Oberlin College. The low note was struck on Saturday morn For nearly forty years Professor Johnson's ing, on the Promenade of the New York courses in nineteenth- and twentieth-century Hilton Hotel (formerly the CAA Registration art have been one of the most popular offer Area). Unbeknownst to us, the space had ings at this prestigious undergraduate institu been contracted to the City-Wide Junior High tion. Her inspired teaching first opened the School Symphonic Orchestra, a group of eyes of numerous students, many of whom some eighty fledgling enthusiasts whose per went on to become leading historians, cura formance could be appreciated only by par tors, critics, and collectors of modern art. -

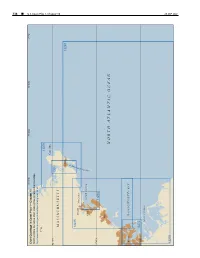

CPB1 C10 WEB.Pdf

338 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 1, Chapter 10 Chapter 1, Pilot Coast U.S. 70°45'W 70°30'W 70°15'W 71°W Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 1—Chapter 10 NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml 71°W 13279 Cape Ann 42°40'N 13281 MASSACHUSETTS Gloucester 13267 R O B R A 13275 H Beverly R Manchester E T S E C SALEM SOUND U O Salem L G 42°30'N 13276 Lynn NORTH ATLANTIC OCEAN Boston MASSACHUSETTS BAY 42°20'N 13272 BOSTON HARBOR 26 SEP2021 13270 26 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 1, Chapter 10 ¢ 339 Cape Ann to Boston Harbor, Massachusetts (1) This chapter describes the Massachusetts coast along and 234 miles from New York. The entrance is marked on the northwestern shore of Massachusetts Bay from Cape its eastern side by Eastern Point Light. There is an outer Ann southwestward to but not including Boston Harbor. and inner harbor, the former having depths generally of The harbors of Gloucester, Manchester, Beverly, Salem, 18 to 52 feet and the latter, depths of 15 to 24 feet. Marblehead, Swampscott and Lynn are discussed as are (11) Gloucester Inner Harbor limits begin at a line most of the islands and dangers off the entrances to these between Black Rock Danger Daybeacon and Fort Point. harbors. (12) Gloucester is a city of great historical interest, the (2) first permanent settlement having been established in COLREGS Demarcation Lines 1623. The city limits cover the greater part of Cape Ann (3) The lines established for this part of the coast are and part of the mainland as far west as Magnolia Harbor.