2 Study Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Provincial Solidarities: a History of the New Brunswick Federation of Labour

provincial solidarities Working Canadians: Books from the cclh Series editors: Alvin Finkel and Greg Kealey The Canadian Committee on Labour History is Canada’s organization of historians and other scholars interested in the study of the lives and struggles of working people throughout Canada’s past. Since 1976, the cclh has published Labour / Le Travail, Canada’s pre-eminent scholarly journal of labour studies. It also publishes books, now in conjunction with AU Press, that focus on the history of Canada’s working people and their organizations. The emphasis in this series is on materials that are accessible to labour audiences as well as university audiences rather than simply on scholarly studies in the labour area. This includes documentary collections, oral histories, autobiographies, biographies, and provincial and local labour movement histories with a popular bent. series titles Champagne and Meatballs: Adventures of a Canadian Communist Bert Whyte, edited and with an introduction by Larry Hannant Working People in Alberta: A History Alvin Finkel, with contributions by Jason Foster, Winston Gereluk, Jennifer Kelly and Dan Cui, James Muir, Joan Schiebelbein, Jim Selby, and Eric Strikwerda Union Power: Solidarity and Struggle in Niagara Carmela Patrias and Larry Savage The Wages of Relief: Cities and the Unemployed in Prairie Canada, 1929–39 Eric Strikwerda Provincial Solidarities: A History of the New Brunswick Federation of Labour / Solidarités provinciales: Histoire de la Fédération des travailleurs et travailleuses du Nouveau-Brunswick David Frank A History of the New Brunswick Federation of Labour david fra nk canadian committee on labour history Copyright © 2013 David Frank Published by AU Press, Athabasca University 1200, 10011 – 109 Street, Edmonton, ab t5j 3s8 isbn 978-1-927356-23-4 (print) 978-1-927356-24-1 (pdf) 978-1-927356-25-8 (epub) A volume in Working Canadians: Books from the cclh issn 1925-1831 (print) 1925-184x (digital) Cover and interior design by Natalie Olsen, Kisscut Design. -

Copyrighted Material

INDEX See also Accommodations and Restaurant indexes, below. GENERAL INDEX best, 9–10 AITO (Association of Blue Hill, 186–187 Independent Tour Brunswick and Bath, Operators), 48 AA (American Automobile A 138–139 Allagash River, 271 Association), 282 Camden, 166–170 Allagash Wilderness AARP, 46 Castine, 179–180 Waterway, 271 Abacus Gallery (Portland), 121 Deer Isle, 181–183 Allen & Walker Antiques Abbe Museum (Acadia Downeast coast, 249–255 (Portland), 122 National Park), 200 Freeport, 132–134 Alternative Market (Bar Abbe Museum (Bar Harbor), Grand Manan Island, Harbor), 220 217–218 280–281 Amaryllis Clothing Co. Acadia Bike & Canoe (Bar green-friendly, 49 (Portland), 122 Harbor), 202 Harpswell Peninsula, Amato’s (Portland), 111 Acadia Drive (St. Andrews), 141–142 American Airlines 275 The Kennebunks, 98–102 Vacations, 50 Acadia Mountain, 203 Kittery and the Yorks, American Automobile Asso- Acadia Mountain Guides, 203 81–82 ciation (AAA), 282 Acadia National Park, 5, 6, Monhegan Island, 153 American Express, 282 192, 194–216 Mount Desert Island, emergency number, 285 avoiding crowds in, 197 230–231 traveler’s checks, 43 biking, 192, 201–202 New Brunswick, 255 American Lighthouse carriage roads, 195 New Harbor, 150–151 Foundation, 25 driving tour, 199–201 Ogunquit, 87–91 American Revolution, 15–16 entry points and fees, 197 Portland, 107–110 America the Beautiful Access getting around, 196–197 Portsmouth (New Hamp- Pass, 45–46 guided tours, 197 shire), 261–263 America the Beautiful Senior hiking, 202–203 Rockland, 159–160 Pass, 46–47 nature -

Natural Landscapes of Maine a Guide to Natural Communities and Ecosystems

Natural Landscapes of Maine A Guide to Natural Communities and Ecosystems by Susan Gawler and Andrew Cutko Natural Landscapes of Maine A Guide to Natural Communities and Ecosystems by Susan Gawler and Andrew Cutko Copyright © 2010 by the Maine Natural Areas Program, Maine Department of Conservation 93 State House Station, Augusta, Maine 04333-0093 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without written permission from the authors or the Maine Natural Areas Program, except for inclusion of brief quotations in a review. Illustrations and photographs are used with permission and are copyright by the contributors. Images cannot be reproduced without expressed written consent of the contributor. ISBN 0-615-34739-4 To cite this document: Gawler, S. and A. Cutko. 2010. Natural Landscapes of Maine: A Guide to Natural Communities and Ecosystems. Maine Natural Areas Program, Maine Department of Conservation, Augusta, Maine. Cover photo: Circumneutral Riverside Seep on the St. John River, Maine Printed and bound in Maine using recycled, chlorine-free paper Contents Page Acknowledgements ..................................................................................... 3 Foreword ..................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ............................................................................................... -

Geology of the Island of Grand Manan, New Brunswick: Precambrian to Early Cambrian and Triassic Formations

GEOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION OF CANADA / MINERALOGICAL ASSOCIATION OF CANADA JOINT ANNUAL MEETING 2014 UNIVERSITY OF NEW BRUNSWICK, FREDERICTON, NEW BRUNSWICK, CANADA FIELD TRIP B3 GEOLOGY OF THE ISLAND OF GRAND MANAN, NEW BRUNSWICK: PRECAMBRIAN TO EARLY CAMBRIAN AND TRIASSIC FORMATIONS MAY 23–25, 2014 J. Gregory McHone 1 and Leslie R. Fyff e 2 1 9 Dexter Lane, Grand Manan, New Brunswick, E5G 3A6 2 Geological Surveys Branch, New Brunswick Department of Energy and Mines, PO Box 6000, Fredericton, New Brunswick, E3B 5H1 i TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures and Tables..............................................................................................................i Safety............................................................................................................................................ 1 Itinerary ......................................................................................................................................... 2 Part 1: Geology of the Island of Grand Manan......................................................................... 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 3 Precambrian Terranes of Southern New Brunswick ..................................................................... 3 Caledonia Terrane ............................................................................................................. 7 Brookville Terrane ............................................................................................................ -

Grand Manan Channel – Southern Part NOAA Chart 13392

BookletChart™ Grand Manan Channel – Southern Part NOAA Chart 13392 A reduced-scale NOAA nautical chart for small boaters When possible, use the full-size NOAA chart for navigation. Published by the 33-foot unmarked rocky patch known as Flowers Rock, 3.9 miles west- northwestward of Machias Seal Island, the channel is free and has a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration good depth of water. The tidal current velocity is about 2.5 knots and National Ocean Service follows the general direction of the channel. Daily predictions are given Office of Coast Survey in the Tidal Current Tables under Bay of Fundy Entrance. Off West Quoddy Head, the currents set in and out of Quoddy Narrows, forming www.NauticalCharts.NOAA.gov strong rips. Sailing vessels should not approach West Quoddy Head too 888-990-NOAA closely with a light wind. North Atlantic Right Whales.–The Bay of Fundy is a feeding and nursery What are Nautical Charts? area for endangered North Atlantic right whales (peak season: July through October) and includes the Grand Manan Basin, a whale Nautical charts are a fundamental tool of marine navigation. They show conservation area designated by the Government of Canada. (See North water depths, obstructions, buoys, other aids to navigation, and much Atlantic Right Whales, chapter 3, for more information on right whales more. The information is shown in a way that promotes safe and and recommended measures to avoid collisions with whales.) efficient navigation. Chart carriage is mandatory on the commercial Southwest Head, the southern extremity of Grand Manan Island, is a ships that carry America’s commerce. -

Real Property Issues in the Marine Aquaculture Industry in New Brunswick

REAL PROPERTY ISSUES IN THE MARINE AQUACULTURE INDUSTRY IN NEW BRUNSWICK SUE NICHOLS IAN EDWARDS JIM DOBBIN KATALIN KOMJATHY SUE HANHAM October 2001 TECHNICAL REPORT NO. 208217 REAL PROPERTY ISSUES IN THE MARINE AQUACULTURE INDUSTRY IN NEW BRUNSWICK Sue Nichols Ian Edwards Jim Dobbin Katalin Komjathy Sue Hanham Department of Geodesy and Geomatics Engineering University ofNew Brunswick P.O. Box 4400 Fredericton, N.B. Canada E3B 5A3 October 2001 PREFACE In order to make our extensive series of technical reports more readily available, we have scanned the old master copies and produced electronic versions in Portable Document Format. The quality of the images varies depending on the quality of the originals. The images have not been converted to searchable text. PREFACE This report was prepared under contract for the New Brunswick Department of Fisheries and Aquaculture. The research was carried out in 1997 at the University of New Brunswick, Fredericton, Canada, under the leadership of Professor Sue Nichols. As with any copyrighted material, permission to reprint or quote extensively from this report must be received from the authors. The citation to this work should appear as follows: Nichols, S., I. Edwards, J. Dobbin, K. Komjathy, and S. Hanham (2001). Real Property Issues in the Marine Aquaculture Industry in New Brunswick. Final contract report for the New Brunswick Department of Fisheries and Aquaculture, by the Geographical Engineering Laboratory, Department of Geodesy and Geomatics Engineering Technical Report No. 208, University of New Brunswick, Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada, 102 pp. Real Property Issues in the Marine Aquaculture Industry in New Brunswick Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank for the Department of Fisheries and Aquaculture for recognising the need for this research and providing the funds. -

CHAPTER 6 Thermal-Hydraulic Design

1 CHAPTER 6 Thermal-Hydraulic Design Prepared by Dr. Nikola K. Popov Summary This chapter covers the thermal-hydraulic design of nuclear power plants with a focus on the primary and secondary sides of the nuclear steam supply system. This chapter covers the following topics: evolution of the reactor thermal-hydraulic system; key design requirements for the heat transport system; thermal-hydraulic design principles and margins; design details of the primary and secondary heat transport systems; fundamentals of two-phase flow; fundamentals of heat transfer and fluid flow in the reactor heat transport system; other related topics. ©UNENE, all rights reserved. For educational use only, no assumed liability. Thermal-Hydraulic Design – December 2015 2 The Essential CANDU Table of Contents 1 Introduction........................................................................................................................... 10 1.1 Overview....................................................................................................................... 10 1.2 Learning outcomes........................................................................................................ 12 1.3 Summary of relationship to other chapters ................................................................... 12 1.4 Thermal-hydraulic design ............................................................................................. 12 2 Reactor Types ...................................................................................................................... -

Emergency Planning at the Point Lepreau Nuclear Generating Station

Emergency Planning at the Point Lepreau Nuclear Generating Station May 2017 Kerrie Blaise, Counsel Publication #1111 ISBN #978-1-77189-817-1 Contents Introduction I. Planning Basis - Emergency Response II. Emergency Response Preparedness III. Emergency Response Planning IV. Emergency Response Measures V. Best Practice and Regulatory Oversight VI. External Hazards – CCNB Report Decision Requested 2 Introduction 3 Introduction About CELA (1) • For nearly 50 years, CELA has used legal tools, undertaken ground breaking research and conducted public interest advocacy to increase environmental protection and the safeguarding of communities • CELA works towards protecting human health and the environment by actively engaging in policy planning and seeking justice for those harmed by pollution or poor environmental decision-making 4 Introduction About CELA (2) Several collections related to CELA's casework in this area include: • Darlington Nuclear Generating Station Refurbishment • Darlington New Build Joint Review Panel • Pickering Nuclear Generating Station Life Extension • Proposed Deep Geologic Repository for Nuclear Waste • Shipping Radioactive Steam Generators in the Great Lakes • These and other related publications are available at: http://www.cela.ca/collections/justice/nuclear-phase- out 5 Introduction About CELA (3) CELA’s full submissions regarding the Point Lepreau Nuclear Generating Station licence renewal are available for download here 6 Introduction Scope of Review (1) Examine the emergency planning provisions Examine relevant -

Environmental Monitoring Report for the Point Lepreau, N.B., Nuclear Generating Station -1984

INIS-mf—11513 Environmental Monitoring Report for the Point Lepreau, N.B., Nuclear Generating Station -1984 R.W.P. Nelson, K.M. Ellis, and J.N. Smith Atlantic Oceanographic Laboratory Department of Fisheries and Oceans Bedford Institute of Oceanography P.O. Box 1006 Dartmouth, Nova Scotia B2Y 4A2 July 1986 Canadian Technical Report of Hydrography and Ocean Sciences No. 75 Canadian Technical Report of Hydrography and Ocean Sciences Technical reports contain scientific and technical information that contributes to existing knowledge but which is not normally appropriate for primary literature. The subject matter is related generally to programs and interests of the Ocean Science and Surveys (OSS) sector of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans. Technical reports may be cited as full publications. The correct citation appears above the abstract of each report. Each report is abstracted in Aquatic Sciences ami Fisheries Abstracts and indexed in the Department's annual index to scientific and technical publications. Technical reports are produced regionally but are numbered nationally. Requests for individual reports will be filled by the issuing establishment listed on the front cover and title page. Out of stock reports will be supplied for a fee by commercial agents. Regional and headquarters establishments of Ocean Science and Surveys ceased publication of their various report series as of December 1981. A complete listing of these publications is published in the Canadian Journal of Fisheries ami Aquatic Sciences, Volume 39: Index to Publications 1982. The current series, which begins with report number 1, was initiated in January 1982. Rapport technique canadien sur l'hydrographie et les sciences oceaniques Les rapports techniques contiennent des renseignements scientifiques et techniques qui constituent une contribution aux connaissances actuelles, mais qui ne sont pas normalement appropries pour la publication dans un journal scientifique. -

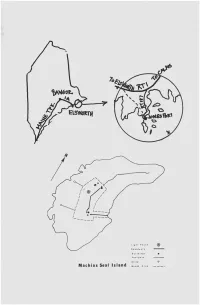

Machias Seal Island Mowad a R I MACHIAS SEAL ISLABD

Foet patK Bltn4 Machias Seal Island Mowad A r i MACHIAS SEAL ISLABD by Paula Butler, Belmont Machias Seal Island— the Contested Island*— has served as a sentinel at the South end of the Bay of Fundy slnce the estahlishment of a lighthouse in 1832. Before that time, this rock (barren except for a highland meadow in summer) vas a marinar's nightmare of sudden fog banks, high seas and hidden rocky shoals. The Harbour Seal, for whioh this island vas probably named, occurs only at a nearby shoal, North Rock. Although today's Journey is quite safe, trips to the island are cancelled vithout notice due to unexpected vind changes or a possible dangerous landing because of ground svells, strong cur- rents and surf. The meadov area of the island contains a variety of plant life: asters, vild parsleys, docks, grasses, sedges, and many other herbs. This island, like many others in the Machias Bay area, vas used for cattle and sheep grazing as vell as Limited farming. Some of these islands vere strategic in the naval maneuvers during the American Revolution. The first naval encounter of that var vas in Machias Bay vhen the villagers of Machias beached the British cutter Margareta. Most birders and photographers are attracted to Machias Seal Island to ob serve Common Puffins (Pratercula árctica) at cióse range. Common Puffins and Razorbills (Alca torda) seem to invite us not only to vatch them but to take delight in posing. Tvo blinds eire provided overlooking the rocky nesting area. The puffins arrive in late April and remain in the vater until they receive a mysterious signal; then, in one large flock, they settle into their nesting sites. -

Point Lepreau Generating Station

cAHoaWf -13- POINT LEPREAU GENERATING STATION BY G. H. D. GANONG/ A. E. STRANG, G. E. GUNTER, T. S. THOMPSON (N B POWER) CNA INTERNATIONAL CONFEBENCE OTTAWA JUNE 16-18, 1975 -14- ABSTRACT The incorporation of this large unit on N B Power's system has been made possible by innovative power system planning and necessary by the price and supply reliability of oil. Project management and the treatment of environmental impact and pub Iic.concern may indicate future patterns for nuclear energy i n Canada. I . INTRODUCTION In July, 1974 it was announced that a CANDU-600 MWe nuclear generating station would be built by N B Power at Point Lepreau on the Bay of Fundy about 24 miles south-west of Saint John. The station is scheduled to be in service in October 1979 and in commercial operation In 1980 to supply future needs for electrical energy in New Brunswick and to provide a measure of relief from dependency upon foreign oil. The introduction of a single 600 MWe unit on the New Brunswick grid offers the economy of size but during the first few years of operation it will present problems with reserve back-up due to its large size relative to other units on the N B system. In an effort to alleviate this problem, a proposal was made in 1973 to supply steam to an AECL owned heavy water plant which would be located on a site adjacent to the nucjear plant. An 800 ton/yr D_0 plant would have reduced the turbine-generator size by 168 MWe. -

Seeing the Light: Report on Staffed Lighthouses in Newfoundland and Labrador and British Columbia

SEEING THE LIGHT: REPORT ON STAFFED LIGHTHOUSES IN NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR AND BRITISH COLUMBIA Report of the Standing Senate Committee on Fisheries and Oceans The Honourable Fabian Manning, Chair The Honourable Elizabeth Hubley, Deputy Chair October 2011 (first published in December 2010) For more information please contact us by email: [email protected] by phone: (613) 990-0088 toll-free: 1 800 267-7362 by mail: Senate Committee on Fisheries and Oceans The Senate of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, K1A 0A4 This report can be downloaded at: http://senate-senat.ca Ce rapport est également disponible en français. MEMBERSHIP The Honourable Fabian Manning, Chair The Honourable Elizabeth Hubley, Deputy Chair and The Honourable Senators: Ethel M. Cochrane Dennis Glen Patterson Rose-Marie Losier-Cool Rose-May Poirier Sandra M. Lovelace Nicholas Vivienne Poy Michael L. MacDonald Nancy Greene Raine Donald H. Oliver Charlie Watt Ex-officio members of the committee: The Honourable Senators James Cowan (or Claudette Tardif) Marjory LeBreton, P.C. (or Claude Carignan) Other Senators who have participated on this study: The Honourable Senators Andreychuk, Chaput, Dallaire, Downe, Marshall, Martin, Murray, P.C., Rompkey, P.C., Runciman, Nancy Ruth, Stewart Olsen and Zimmer. Parliamentary Information and Research Service, Library of Parliament: Claude Emery, Analyst Senate Committees Directorate: Danielle Labonté, Committee Clerk Louise Archambeault, Administrative Assistant ORDER OF REFERENCE Extract from the Journals of the Senate, Sunday, June