THE CASE of BAVARIA 91 the Separatism That Neve

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The GDR's Westpolitik and Everyday Anticommunism in West Germany

Philosophische Fakultät Dierk Hoffmann The GDR’s Westpolitik and everyday anticommunism in West Germany Suggested citation referring to the original publication: Asian Journal of German and European Studies 2 (2017) 11 DOI https://doi.org/10.1186/s40856-017-0022-5 ISSN (online) 2199-4579 Postprint archived at the Institutional Repository of the Potsdam University in: Postprints der Universität Potsdam Philosophische Reihe ; 167 ISSN 1866-8380 http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:kobv:517-opus4-435184 DOI https://doi.org/10.25932/publishup-43518 Hoffmann Asian Journal of German and European Studies (2017) 2:11 Asian Journal of German DOI 10.1186/s40856-017-0022-5 and European Studies CASE STUDY Open Access The GDR’s Westpolitik and everyday anticommunism in West Germany Dierk Hoffmann1,2 Correspondence: hoffmann@ifz- muenchen.de Abstract 1 Potsdam University, Berlin, ’ Germany West German anticommunism and the SED s Westarbeit were to some extent 2Institut fur Zeitgeschichte interrelated. From the beginning, each German state had attemted to stabilise its Munchen Berlin Abteilung, Berlin, own social system while trying to discredit its political opponent. The claim to Germany sole representation and the refusal to acknowledge each other delineated governmental action on both sides. Anticommunism in West Germany re-developed under the conditions of the Cold War, which allowed it to become virtually the reason of state and to serve as a tool for the exclusion of KPD supporters. In its turn, the SED branded the West German State as ‘revanchist’ and instrumentalised its anticommunism to persecute and eliminate opponents within the GDR. Both phenomena had an integrative and exclusionary element. -

30Years 1953-1983

30Years 1953-1983 Group of the European People's Party (Christian -Demoeratie Group) 30Years 1953-1983 Group of the European People's Party (Christian -Demoeratie Group) Foreword . 3 Constitution declaration of the Christian-Democratic Group (1953 and 1958) . 4 The beginnings ............ ·~:.................................................. 9 From the Common Assembly to the European Parliament ........................... 12 The Community takes shape; consolidation within, recognition without . 15 A new impetus: consolidation, expansion, political cooperation ........................................................... 19 On the road to European Union .................................................. 23 On the threshold of direct elections and of a second enlargement .................................................... 26 The elected Parliament - Symbol of the sovereignty of the European people .......... 31 List of members of the Christian-Democratic Group ................................ 49 2 Foreword On 23 June 1953 the Christian-Democratic Political Group officially came into being within the then Common Assembly of the European Coal and Steel Community. The Christian Democrats in the original six Community countries thus expressed their conscious and firm resolve to rise above a blinkered vision of egoistically determined national interests and forge a common, supranational consciousness in the service of all our peoples. From that moment our Group, whose tMrtieth anniversary we are now celebrating together with thirty years of political -

CALENDRIER Du 11 Février Au 17 Février 2019 Brussels, 8 February 2019 (Susceptible De Modifications En Cours De Semaine) Déplacements Et Visites

European Commission - Weekly activities CALENDRIER du 11 février au 17 février 2019 Brussels, 8 February 2019 (Susceptible de modifications en cours de semaine) Déplacements et visites Lundi 11 février 2019 Eurogroup President Jean-Claude Juncker receives Mr Frank Engel, Member of the European Parliament. President Jean-Claude Juncker receives Mr Sven Giegold, Member of the European Parliament. President Jean-Claude Juncker receives Mr Joseph Daul, President of the European People's Party and Manfred Weber, Chairman of the EPP Group, in the European Parliament. President Jean-Claude Juncker receives Mr José Ignacio Salafranca, Member of the European Parliament. Mr Jyrki Katainen receives representatives of the Medicines for Europe Association. Mr Günther H. Oettinger in Berlin, Germany: meets representatives of the German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP). Mr Pierre Moscovici à Berlin, en Allemagne : participe à une réunion du parti social-démocrate allemande, (SPD). Mr Christos Stylianides in Barcelona, Spain: meets Mr Antoni Segura, President of the Barcelona Centre for International Affairs; participates in a debate on Civil Protection at the Barcelona Centre for International Affairs; holds a speech at an information seminar on the European Solidarity Corps; holds a speech at the third meeting of Civil Protection Director-Generals of the Member States of the Union for the Mediterranean; and holds a speech at an event on Forest Fire Prevention at the European Forest Institute Mediterranean Facility. Mr Phil Hogan in Sydney, Australia: visits the University of Sydney Institute of Agriculture. Ms Mariya Gabriel in Berlin, Germany: visits the John Lennon Gymnasium together with filmmaker Wim Wenders and delivers a speech on Safer Internet. -

Wiederaufbau Von Wirtschaft Und Verwaltung

IV Der Wiederaufbau von Wirtschaft und Verwaltung Neuanfang unter amerikanischer Flagge Wiederbelebung sozialdemokratischer Ortsvereine Wilhelm Hoegners erste Regierungszeit Die Wiedergründung des bayerischen Landesverbandes der SPD Der Bayerische Beratende Landesausschuss Der Weg zur Bayerischen Verfassung Erster Bayerischer Landtag 1946: Koalition mit der CSU Bayerns SPD erstmals in der Opposition (1947–1950) Streitfall Grundgesetz – Wahlen zum ersten Deutschen Bundestag Zweiter Bayerischer Landtag 1950: erneute Koalition mit der CSU Dritter Landtag 1954: die Viererkoalition und ihr Ende Bayerische Landtagswahl 1958: SPD wieder in der Opposition Wirtschaft Die bayerische SPD und das Godesberger Programm Wiederaufbau Fünfter Bayerischer Landtag 1962: Generationswechsel in der SPD Verwaltung 95 IV DER WIEDERAUFBAU VON WIRTSCHAFT UND VERWALTUNG Neuanfang unter amerikanischer Flagge Das Ende der Die Einnahme Bayerns durch US-amerikanische Schiefer und mit Thomas Wimmer, dem späteren nationalsozialistischen Tr uppen vollzog sich innerhalb weniger Wochen; sie Oberbürgermeister von München. Die beiden Sozial- Diktatur begann am 25. März 1945 nördlich von Aschaffen- demokraten sandten Schäffer am 22. Mai 1945 eine burg und endete am 4. Mai mit der Übergabe von Liste mit Personalvorschlägen „ministrabler“ SPD- Berchtesgaden. Mit der bedingungslosen Kapitula- Kandidaten, auf der unter anderem die früheren tion des Deutschen Reiches am 8. Mai 1945 war die Landtagsabgeordneten Albert Roßhaupter, Wilhelm zwölfjährige nationalsozialistische Diktatur -

Mario Draghi: Laudatio for Theo Waigel

Mario Draghi: Laudatio for Theo Waigel Speech by Mr Mario Draghi, President of the European Central Bank, in honour of Dr Theodor Waigel, at SignsAwards, Munich, 17 June 2016. * * * James Freeman Clarke, a 19th century theologian, once observed that “a politician is a man who thinks of the next election, while a statesman thinks of the next generation”. This captures well why we are here to honour Theo Waigel today. Theo Waigel’s political career cannot just be defined by the elections he won, however many there were during his 30 years in the Bundestag. Nor can it be defined by his time as head of the CSU and as finance minister of Germany. It is defined by his legacy: a legacy that is still shaping Europe today. He became finance minister in 1989 at a turning-point in post-war European history – when the Iron Curtain that divided Europe was being lifted; when the walls and barbed wire that divided Germany were being removed. It was a time of great hopes and expectations. But it was also a time of some anxiety. It was clear that the successful reunification of Germany would be a tremendous undertaking. And many wondered what those changes would mean for the European Community – whether it would upset the balance of power that had prevailed between nations since the war. In that uncertain setting, Theo Waigel’s leadership was pivotal – both as a German and as a European. He was one of the strongest advocates of German reunification, and was instrumental in getting Germany’s federal and state governments to finance the reconstruction and modernisation of East Germany. -

The Neglected Nation: the CSU and the Territorial Cleavage in Bavarian Party Politics’', German Politics, Vol

Edinburgh Research Explorer ‘The Neglected Nation: The CSU and the Territorial Cleavage in Bavarian Party Politics’ Citation for published version: Hepburn, E 2008, '‘The Neglected Nation: The CSU and the Territorial Cleavage in Bavarian Party Politics’', German Politics, vol. 17(2), pp. 184-202. Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: German Politics Publisher Rights Statement: © Hepburn, E. (2008). ‘The Neglected Nation: The CSU and the Territorial Cleavage in Bavarian Party Politics’. German Politics, 17(2), 184-202 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. Sep. 2021 © Hepburn, E. (2008). ‘The Neglected Nation: The CSU and the Territorial Cleavage in Bavarian Party Politics’. German Politics, 17(2), 184-202. The Neglected Nation: The CSU and the Territorial Cleavage in Bavarian Party Politics Eve Hepburn, School of Social and Political Studies, University of Edinburgh1 ABSTRACT This article examines the continuing salience of the territorial cleavage in Bavarian party politics. It does so through an exploration of the Christian Social Union’s (CSU) mobilisation of Bavarian identity as part of its political project, which has forced other parties in Bavaria to strengthen their territorial goals and identities. -

What Does GERMANY Think About Europe?

WHat doEs GERMaNY tHiNk aboUt europE? Edited by Ulrike Guérot and Jacqueline Hénard aboUt ECFR The European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) is the first pan-European think-tank. Launched in October 2007, its objective is to conduct research and promote informed debate across Europe on the development of coherent, effective and values-based European foreign policy. ECFR has developed a strategy with three distinctive elements that define its activities: •a pan-European Council. ECFR has brought together a distinguished Council of over one hundred Members - politicians, decision makers, thinkers and business people from the EU’s member states and candidate countries - which meets once a year as a full body. Through geographical and thematic task forces, members provide ECFR staff with advice and feedback on policy ideas and help with ECFR’s activities within their own countries. The Council is chaired by Martti Ahtisaari, Joschka Fischer and Mabel van Oranje. • a physical presence in the main EU member states. ECFR, uniquely among European think-tanks, has offices in Berlin, London, Madrid, Paris, Rome and Sofia. In the future ECFR plans to open offices in Warsaw and Brussels. Our offices are platforms for research, debate, advocacy and communications. • a distinctive research and policy development process. ECFR has brought together a team of distinguished researchers and practitioners from all over Europe to advance its objectives through innovative projects with a pan-European focus. ECFR’s activities include primary research, publication of policy reports, private meetings and public debates, ‘friends of ECFR’ gatherings in EU capitals and outreach to strategic media outlets. -

The Committee on Economic Cooperation and Development

The Committee on Economic Cooperation and Development 2 “The central challenge in develop- ment cooperation is and remains for the state, businesses and society to work together to provide impe- tus to people in partner countries to help themselves. We can achieve this if we cooperate globally to bring about a shift away from short-term crisis management and towards a strategy of sustainable development. Local populations need to muster the creative power to make the most of their potential. The members of the Committee put their confidence in committed people who work to create a decent future in their home countries.” Dr Peter Ramsauer, CDU/CSU Chairman of the Committee on Economic Cooperation and Development 3 The German Bundestag’s decisions are prepared by its committees, which are estab- lished at the start of each elec- toral term. Four of them are stipulated by the Basic Law, the German constitution: the Committee on Foreign Affairs, the Defence Committee, the Committee on the Affairs of the European Union and the Petitions Committee. The Budget Committee and the Committee for the Rules of Procedure are also required by law. The spheres of respon- sibility of the committees essentially reflect the Federal Government’s distribution of ministerial portfolios. This enables Parliament to scruti- nise the government’s work effectively. The Bundestag committees The German Bundestag sets political priorities of its own by establishing additional committees for specific sub- jects, such as sport, cultural affairs or tourism. In addition, special bodies such as parlia- mentary advisory councils, The committees discuss and committees of inquiry or deliberate on items referred study commissions can also to them by the plenary. -

Commander's Guide to German Society, Customs, and Protocol

Headquarters Army in Europe United States Army, Europe, and Seventh Army Pamphlet 360-6* United States Army Installation Management Agency Europe Region Office Heidelberg, Germany 20 September 2005 Public Affairs Commanders Guide to German Society, Customs, and Protocol *This pamphlet supersedes USAREUR Pamphlet 360-6, 8 March 2000. For the CG, USAREUR/7A: E. PEARSON Colonel, GS Deputy Chief of Staff Official: GARY C. MILLER Regional Chief Information Officer - Europe Summary. This pamphlet should be used as a guide for commanders new to Germany. It provides basic information concerning German society and customs. Applicability. This pamphlet applies primarily to commanders serving their first tour in Germany. It also applies to public affairs officers and protocol officers. Forms. AE and higher-level forms are available through the Army in Europe Publishing System (AEPUBS). Records Management. Records created as a result of processes prescribed by this publication must be identified, maintained, and disposed of according to AR 25-400-2. Record titles and descriptions are available on the Army Records Information Management System website at https://www.arims.army.mil. Suggested Improvements. The proponent of this pamphlet is the Office of the Chief, Public Affairs, HQ USAREUR/7A (AEAPA-CI, DSN 370-6447). Users may suggest improvements to this pamphlet by sending DA Form 2028 to the Office of the Chief, Public Affairs, HQ USAREUR/7A (AEAPA-CI), Unit 29351, APO AE 09014-9351. Distribution. B (AEPUBS) (Germany only). 1 AE Pam 360-6 ● 20 Sep 05 CONTENTS Section I INTRODUCTION 1. Purpose 2. References 3. Explanation of Abbreviations 4. General Section II GETTING STARTED 5. -

Der Imagewandel Von Helmut Kohl, Gerhard Schröder Und Angela Merkel Vom Kanzlerkandidaten Zum Kanzler - Ein Schauspiel in Zwei Akten

Forschungsgsgruppe Deutschland Februar 2008 Working Paper Sybille Klormann, Britta Udelhoven Der Imagewandel von Helmut Kohl, Gerhard Schröder und Angela Merkel Vom Kanzlerkandidaten zum Kanzler - Ein Schauspiel in zwei Akten Inszenierung und Management von Machtwechseln in Deutschland 02/2008 Diese Veröffentlichung entstand im Rahmen eines Lehrforschungsprojektes des Geschwister-Scholl-Instituts für Politische Wissenschaft unter Leitung von Dr. Manuela Glaab, Forschungsgruppe Deutschland am Centrum für angewandte Politikforschung. Weitere Informationen unter: www.forschungsgruppe-deutschland.de Inhaltsverzeichnis: 1. Die Bedeutung und Bewertung von Politiker – Images 3 2. Helmut Kohl: „Ich werde einmal der erste Mann in diesem Lande!“ 7 2.1 Gut Ding will Weile haben. Der „Lange“ Weg ins Kanzleramt 7 2.2 Groß und stolz: Ein Pfälzer erschüttert die Bonner Bühne 11 2.3 Der richtige Mann zur richtigen Zeit: Der Mann der deutschen Mitte 13 2.4 Der Bauherr der Macht 14 2.5 Kohl: Keine Richtung, keine Linie, keine Kompetenz 16 3. Gerhard Schröder: „Ich will hier rein!“ 18 3.1 „Hoppla, jetzt komm ich!“ Schröders Weg ins Bundeskanzleramt 18 3.2 „Wetten ... dass?“ – Regieren macht Spass 22 3.3 Robin Hood oder Genosse der Bosse? Wofür steht Schröder? 24 3.4 Wo ist Schröder? Vom „Gernekanzler“ zum „Chaoskanzler“ 26 3.5 Von Saumagen, Viel-Sagen und Reformvorhaben 28 4. Angela Merkel: „Ich will Deutschland dienen.“ 29 4.1 Fremd, unscheinbar und unterschätzt – Merkels leiser Aufstieg 29 4.2 Die drei P’s der Merkel: Physikerin, Politikerin und doch Phantom 33 4.3 Zwischen Darwin und Deutschland, Kanzleramt und Küche 35 4.4 „Angela Bangbüx“ : Versetzung akut gefährdet 37 4.5 Brutto: Aus einem Guss – Netto: Zuckerguss 39 5. -

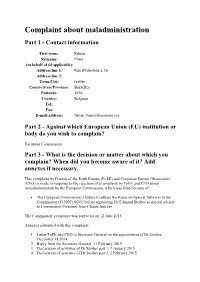

Complaint About Maladministration Part 1 - Contact Information

Complaint about maladministration Part 1 - Contact information First name: Fabian Surname: Flues On behalf of (if applicable): Address line 1: Rue d'Edimbourg 26 Address line 2: Town/City: Ixelles County/State/Province: Bruxelles Postcode: 1050 Country: Belgium Tel.: Fax: E-mail address: [email protected] Part 2 - Against which European Union (EU) institution or body do you wish to complain? European Commission Part 3 - What is the decision or matter about which you complain? When did you become aware of it? Add annexes if necessary. This complaint by Friends of the Earth Europe (FoEE) and Corporate Europe Observatory (CEO) is made in response to the rejection of a complaint by FoEE and CEO about maladministration by the European Commission, which was filed because of: The European Commission’s failure to adhere the Rules on Special Advisers to the Commission (C(2007) 6655) before appointing Dr Edmund Stoiber as special adviser to Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker The Commission’s response was sent to us on 12 June 2015. Annexes submitted with this complaint: 1. Letter FoEE and CEO to Secretary General on the appointment of Dr Stoiber, December 18 2014 2. Reply from the Secretary General, 11 February 2015 3. Declaration of activities of Dr Stoiber part 1, 7 January 2015 4. Declaration of activities of Dr Stoiber part 2, 2 February 2015 5. Declaration of honour of Dr Stoiber 7 January 2015 6. Response Secretary General to FoEE and CEO questions, 16 February 2015 7. Letter FoEE and CEO to Secretary General requesting reconsideration, 25 May 2015 8. -

Rebuilding the Soul: Churches and Religion in Bavaria, 1945-1960

REBUILDING THE SOUL: CHURCHES AND RELIGION IN BAVARIA, 1945-1960 _________________________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy _________________________________________________ by JOEL DAVIS Dr. Jonathan Sperber, Dissertation Supervisor MAY 2007 © Copyright by Joel Davis 2007 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled REBUILDING THE SOUL: CHURCHES AND RELIGION IN BAVARIA, 1945-1960 presented by Joel Davis, a candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. __________________________________ Prof. Jonathan Sperber __________________________________ Prof. John Frymire __________________________________ Prof. Richard Bienvenu __________________________________ Prof. John Wigger __________________________________ Prof. Roger Cook ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe thanks to a number of individuals and institutions whose help, guidance, support, and friendship made the research and writing of this dissertation possible. Two grants from the German Academic Exchange Service allowed me to spend considerable time in Germany. The first enabled me to attend a summer seminar at the Universität Regensburg. This experience greatly improved my German language skills and kindled my deep love of Bavaria. The second allowed me to spend a year in various archives throughout Bavaria collecting the raw material that serves as the basis for this dissertation. For this support, I am eternally grateful. The generosity of the German Academic Exchange Service is matched only by that of the German Historical Institute. The GHI funded two short-term trips to Germany that proved critically important.