Notes on the Seabirds of Round Island, Mauritius

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Behavior and Attendance Patterns of the Fork-Tailed Storm-Petrel

BEHAVIOR AND ATTENDANCE PATTERNS OF THE FORK-TAILED STORM-PETREL THEODORE R. SIMONS Wildlife Science Group, Collegeof Forest Resources, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington 98195 USA ABSTRACT.--Behavior and attendance patterns of breeding Fork-tailed Storm-Petrels (Ocea- nodromafurcata) were monitored over two nesting seasonson the Barren Islands, Alaska. The asynchrony of egg laying and hatching shown by these birds apparently reflects the influence of severalfactors, including snow conditionson the breedinggrounds, egg neglectduring incubation, and food availability. Communication between breeding birds was characterized by auditory and tactile signals.Two distinct vocalizationswere identified, one of which appearsto be a sex-specific call given by males during pair formation. Generally, both adults were present in the burrow on the night of egg laying, and the male took the first incubation shift. Incubation shiftsranged from 1 to 5 days, with 2- and 3-day shifts being the most common. Growth parameters of the chicks, reproductive success, and breeding chronology varied considerably between years; this pre- sumably relates to a difference in conditions affecting the availability of food. Adults apparently responded to changes in food availability during incubation by altering their attendance patterns. When conditionswere good, incubation shifts were shorter, egg neglectwas reduced, and chicks were brooded longer and were fed more frequently. Adults assistedthe chick in emerging from the shell. Chicks became active late in the nestling stage and began to venture from the burrow severaldays prior to fledging. Adults continuedto visit the chick during that time but may have reducedthe amountof fooddelivered. Chicks exhibiteda distinctprefledging weight loss.Received 18 September1979, accepted26 July 1980. -

Acoustic Attraction of Grey-Faced Petrels (Pterodroma Macroptera Gouldi) and Fluttering Shearwaters (Puffinus Gavia) to Young Nick’S Head, New Zealand

166 Notornis, 2010, Vol. 57: 166-168 0029-4470 © The Ornithological Society of New Zealand, Inc. SHORT NOTE Acoustic attraction of grey-faced petrels (Pterodroma macroptera gouldi) and fluttering shearwaters (Puffinus gavia) to Young Nick’s Head, New Zealand STEVE L. SAWYER* Ecoworks NZ Ltd, 369 Wharerata Road, RD1, Gisborne 4071, New Zealand SALLY R. FOGLE Ecoworks NZ Ltd, 369 Wharerata Road, RD1, Gisborne 4071, New Zealand Burrow-nesting and surface-nesting petrels colonies at sites following extirpation or at novel (Families Procellariidae, Hydrobatidae and nesting habitats, as the attraction of prospecting Oceanitidae) in New Zealand have been severely non-breeders to a novel site is unlikely and the affected by human colonisation, especially through probabilities of recolonisation further decrease the introduction of new predators (Taylor 2000). as the remaining populations diminish (Gummer Of the 41 extant species of petrel, shearwater 2003). and storm petrels in New Zealand, 35 species are Both active (translocation) and passive (social categorised as ‘threatened’ or ‘at risk’ with 3 species attraction) methods have been used in attempts to listed as nationally critical (Miskelly et al. 2008). establish or restore petrel colonies (e.g. Miskelly In conjunction with habitat protection, habitat & Taylor 2004; Podolsky & Kress 1992). Methods enhancement and predator control, the restoration for the translocation of petrel chicks to new colony of historic colonies or the attraction of petrels to sites are now fairly well established, with fledging new sites is recognised as important for achieving rates of 100% achievable, however, the return of conservation and species recovery objectives translocated chicks to release sites is still awaiting (Aikman et al. -

Geographic Variation in Leach's Storm-Petrel

GEOGRAPHIC VARIATION IN LEACH'S STORM-PETREL DAVID G. AINLEY Point Reyes Bird Observatory, 4990 State Route 1, Stinson Beach, California 94970 USA ABSTRACT.-•A total of 678 specimens of Leach's Storm-Petrels (Oceanodroma leucorhoa) from known nestinglocalities was examined, and 514 were measured. Rump color, classifiedon a scale of 1-11 by comparison with a seriesof reference specimens,varied geographicallybut was found to be a poor character on which to base taxonomic definitions. Significant differences in five size charactersindicated that the presentlyaccepted, but rather confusing,taxonomy should be altered: (1) O. l. beali, O. l. willetti, and O. l. chapmani should be merged into O. l. leucorhoa;(2) O. l. socorroensisshould refer only to the summer breeding population on Guadalupe Island; and (3) the winter breeding Guadalupe population should be recognizedas a "new" subspecies,based on physiological,morphological, and vocal characters,with the proposedname O. l. cheimomnestes. The clinal and continuoussize variation in this speciesis related to oceanographicclimate, length of migration, mobility during the nesting season,and distancesbetween nesting islands. Why oceanitidsfrequenting nearshore waters during nestingare darker rumped than thoseoffshore remains an unanswered question, as does the more basic question of why rump color varies geographicallyin this species.Received 15 November 1979, accepted5 July 1980. DURING field studies of Leach's Storm-Petrels (Oceanodroma leucorhoa) nesting on Southeast Farallon Island, California in 1972 and 1973 (see Ainley et al. 1974, Ainley et al. 1976), several birds were captured that had dark or almost completely dark rumps. The subspecificidentity of the Farallon population, which at that time was O. -

The Rise and Fall of Bulwer's Petrel

A paper from the British Ornithologists’ Union Records Committee The rise and fall of Bulwer’s Petrel Andrew H. J. Harrop ABSTRACT This short paper examines two recent reviews of records of Bulwer’s Petrel Bulweria bulwerii in Britain by BOURC. Four records were assessed, including three specimen records from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and a modern-day sighting from Cumbria. None was found acceptable, and the reasons are discussed here. ulwer’s Petrel Bulweria bulwerii was By the time The Handbook was published, seven named after Rev. James Bulwer, an records were listed for Britain, all in England Bamateur Norfolk collector, naturalist and (Witherby et al. 1940), and these were repeated conchologist, who first collected it in Madeira, in Bannerman’s The Birds of the British Isles probably in 1825 during a short expedition to (1959). Of these seven, four (all from Sussex, Deserta Grande (Mearns & Mearns 1988). It between 1904 and 1914) were subsequently was first described by Sir William Jardine and rejected as ‘Hastings Rarities’ (Nicholson & Fer- Prideaux John Selby, in Illustrations of guson-Lees 1962; see plate 380) and a fifth, said Ornithology in 1828 (Jardine & Selby 1828). The to have been picked up at Beachy Head, Sussex, species has had a turbulent history as a British by an unnamed person on 3rd February 1903, bird. This paper provides a brief summary of escaped this fate only because it occurred records in the British ornithological literature, outside the area used to define ‘Hastings’ presents the results of two BOURC reviews, and records (Bourne 1967). -

Management Plan for Antarctic Specially Protected Area No

Measure 2 (2005) Annex E Management Plan for Antarctic Specially Protected Area No. 120 POINTE-GÉOLOGIE ARCHIPELAGO, TERRE ADÉLIE Jean Rostand, Le Mauguen (former Alexis Carrel), Lamarck and Claude Bernard Islands, The Good Doctor’s Nunatak and breeding site of Emperor Penguins 1. Description of Values to be Protected In 1995, four islands, a nunatak and a breeding ground for emperor penguins were classified as an Antarctic Specially Protected Area (Measure 3 (1995), XIX ATCM, Seoul) because they were a representative example of terrestrial Antarctic ecosystems from a biological, geological and aesthetics perspective. A species of marine mammal, the Weddell seal (Leptonychotes weddelli) and various species of birds breed in the area: emperor penguin (Aptenodytes forsteri); Antarctic skua (Catharacta maccormicki); Adélie penguins (Pygoscelis adeliae); Wilson’s petrel (Oceanites oceanicus); giant petrel (Macronectes giganteus); snow petrel (Pagodrama nivea), cape petrel (Daption capense). Well-marked hills display asymmetrical transverse profiles with gently dipping northern slopes compared to the steeper southern ones. The terrain is affected by numerous cracks and fractures leading to very rough surfaces. The basement rocks consist mainly of sillimanite, cordierite and garnet-rich gneisses which are intruded by abundant dikes of pink anatexites. The lowest parts of the islands are covered by morainic boulders with a heterogenous granulometry (from a few cm to more than a m across). Long-term research and monitoring programs of birds and marine mammals have been going on for a long time already (since 1952 or 1964 according to the species). A database implemented in 1981 is directed by the Centre d'Etudes Biologiques de Chize (CEBC-CNRS). -

Albatross and Giant-Petrel Distribution Across the World's Tuna And

The Third Joint Tuna RFMOs meeting; La Jolla, July 11-15, 2011 s e l l e c s a L B - s e s s o r t b l a g n i y l F ; F T A / n e r o G M - e n li g n o l n o s s o r t a b l a Albatross and giant-petrel distribution across the world’s tuna and swordfish fisheries R. Alderman1, D. Anderson2, J. Arata3, P. Catry4, R. Cuthbert5, L. Deppe6, G. Elliot7, R. Gales1, J. Gonzales Solis9, J.P. Granadeiro10, M. Hester11, N. Huin12, D. Hyrenbach13, K. Layton14, D. Nicholls15, K. Ozak16, S. Peterson17, R.A. Phillips18, F. Quintana19, G. R. Balogh20, C. Robertson21, G. Robertson14, P. Sagar22, F. Sato16, S. Shaffer23, C. Small5, J. Stahl24, R. Suryan25, P. Taylor26, D. Thompson22, K. Walker7, R. Wanless27, S. Waugh24, H. Weimerskirch28 Summary More than 90% of albatross and giant Albatrosses are vulnerable to bycatch in tuna and swordfish longline fisheries. petrel global distribution overlaps Remote tracking data provide a key tool to identifying priority areas for with the areas managed by the tuna seabird bycatch mitigation. This paper presents an updated analysis of the global distribution of albatrosses and giant-petrels using data from the Global commissions Procellariiform Tracking Database. Overall, 91% of global albatross and giant- petrel distribution during the breeding season and 92% of global albatross and giant-petrel distribution during the non-breeding season, overlaps with the areas Results emphasise the importance of managed by the tuna commissions. -

Herald Petrel New to the West Indies

EXTRALIMITAL RECORD Herald Petrel new to the West Indies Michael Gochfeld,Joanna Burger, Jorge Saliva, and Deborah Gochfeld (Pterodroma)are bestrepresented SinA southGROUP temperate THEGADFLY and subantarc-PETRELS tic waterswith a few speciesbreeding on tropicalislands in the Central Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans.In the West Indies,the only member of this genusis the Black-cappedPetrel (P hasitata), which breeds in the Greater Antilles and perhaps still in the Lesser Antilles. A dose relative,the endangeredBermuda (P..cahow) breeds in Bermuda. On July 12, 1986, while studyingthe breeding Laughing Gulls (Larus atri- cilia), Royal Terns,and SandwichTerns (Sterna maxima and S. sandvicensis)on Cayo Lobito, in the Culebra National Wildlife Refuge, about 40 kilometers eastof Fajardo,Puerto Rico, we flushed an all-dark petrel from a scrapeamong the nestingterns. As soon as the bird wheeled around we realized that it was a petrel, and not the familiar Sooty Shearwater(Puj•nus griseus),a species Figure 1. Dark-phasePterodroma landing among Laughing Gulls on Cayo Lobito. Culebra, which would itselfbe extremelyunusual PuertoRico. Note the ashygray undersurface of theprimary.feathers, ending in longnarrow at Culebra. Compared to a shearwater, "digital" extensionsthat are the pale areas of the inner websof theprimaries. The greater the petrelappeared to havea largerhead underwingcoverts are pale with a narrowdark tip that showsas thefaint wavybar at the base of theprimaries. The Iongishtail and shortishbill are apparent. and a longerand slightlywedge-shaped tail. It did not showthe conspicuouspale wing linings of the Sooty Shearwater (Fig. 1). The bird circled rapidly, first low over the water and then wheeling high overthe rocky islet,before return- ing to its scrapeamong the gulls and terns. -

Conservation Action Plan Black-Capped Petrel

January 2012 Conservation Action Plan for the Black-capped Petrel (Pterodroma hasitata) Edited by James Goetz, Jessica Hardesty-Norris and Jennifer Wheeler Contact Information for Editors: James Goetz Cornell Lab of Ornithology Cornell University Ithaca, New York, USA, E-mail: [email protected] Jessica Hardesty-Norris American Bird Conservancy The Plains, Virginia, USA E-mail: [email protected] Jennifer Wheeler U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Arlington, Virginia, USA E-mail: [email protected] Suggested Citation: Goetz, J.E., J. H. Norris, and J.A. Wheeler. 2011. Conservation Action Plan for the Black-capped Petrel (Pterodroma hasitata). International Black-capped Petrel Conservation Group http://www.fws.gov/birds/waterbirds/petrel Funding for the production of this document was provided by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Table Of Contents Introduction . 1 Status Assessment . 3 Taxonomy ........................................................... 3 Population Size And Distribution .......................................... 3 Physical Description And Natural History ................................... 4 Species Functions And Values ............................................. 5 Conservation And Legal Status ............................................ 6 Threats Assessment ..................................................... 6 Current Management Actions ............................................ 8 Accounts For Range States With Known Or Potential Breeding Populations . 9 Account For At-Sea (Foraging) Range .................................... -

Identifying Giant Petrels, Macronectes Giganteus and M. Halli, in the Field and in the Hand

Identification of giant petrels Identifying giant petrels, Macronectes giganteus and M. halli, in the field and in the hand Carlos, C. J.1,2*, & Voisin, J.-F.3 *Correspondence author. Email: [email protected] or [email protected] 1 Laboratório de Elasmobrânquios e Aves Marinhas, Departamento de Oceanografia, Fundação Universidade Federal do Rio Grande, CP 474, 96201-900, Rio Grande, RS, Brazil; 2 Current address: Rua Mário Damiani Panatta 680, Cinqüentenário, 95013-290, Caxias do Sul, RS, Brazil; 3 USM 305, Département Ecologie et Gestion de la Biodiversité, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, CP 51, 57 rue Cuvier, F-75 005 Paris, France. Abstract The two similar-looking species of giant petrels, the Northern Giant Petrel Macronectes halli and the Southern Giant Petrel M. giganteus, are renowned for being difficult to identify. In this paper we review and offer new guidelines on identification of these birds at sea, on land, and as dead specimens. Criteria for identifying giant petrels are available in the scientific literature, especially regarding bill-tip coloration which readily differ from one species to another. Plumage characters, although useful to discriminate species, are not adequately covered at present. Thus, for each species we describe in detail and illustrate distinctive age-related plumage stages, or types, from juveniles through to adult breeders.We also comment on giant petrel biometrics, body weight, and some aspects of their behaviour, in order to help ornithologists and birdwatchers separate males and females, and eventually specimens from South America–Gough Island, Antarctic and sub-Antarctic regions. Introduction Giant petrels Macronectes are large Procellariiformes with a wingspan usually in excess of two meters in males, slightly less in females, and are similar in size to Thalassarche mollymawks. -

Analysis of Albatross and Petrel Distribution Within the CCAMLR Convention Area: Results from the Global Procellariiform Tracking Database

CCAMLR Science, Vol. 13 (2006): 143–174 ANALYSIS OF ALBATROSS AND PETREL DISTRIBUTION WITHIN THE CCAMLR CONVENTION AREA: RESULTS FROM THE GLOBAL PROCELLARIIFORM TRACKING DATABASE BirdLife International (prepared by C. Small and F. Taylor) Wellbrook Court, Girton Road Cambridge CB3 0NA United Kingdom Correspondence address: BirdLife Global Seabird Programme c/o Royal Society for the Protection of Birds The Lodge, Sandy Bedfordshire SG19 2DL United Kingdom Email – [email protected] Abstract CCAMLR has implemented successful measures to reduce the incidental mortality of seabirds in most of the fisheries within its jurisdiction, and has done so through area- specific risk assessments linked to mandatory use of measures to reduce or eliminate incidental mortality, as well as through measures aimed at reducing illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing. This paper presents an analysis of the distribution of albatrosses and petrels in the CCAMLR Convention Area to inform the CCAMLR risk- assessment process. Albatross and petrel distribution is analysed in terms of its division into FAO areas, subareas, divisions and subdivisions, based on remote-tracking data contributed to the Global Procellariiform Tracking Database by multiple data holders. The results highlight the importance of the Convention Area, particularly for breeding populations of wandering, grey-headed, light-mantled, black-browed and sooty albatross, and populations of northern and southern giant petrel, white-chinned petrel and short- tailed shearwater. Overall, the subareas with the highest proportion of albatross and petrel breeding distribution were Subareas 48.3 and 58.6, adjacent to the southwest Atlantic Ocean and southwest Indian Ocean, but albatross and petrel breeding ranges extend across the majority of the Convention Area. -

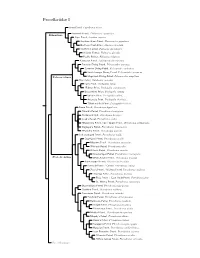

Procellariidae Species Tree

Procellariidae I Snow Petrel, Pagodroma nivea Antarctic Petrel, Thalassoica antarctica Fulmarinae Cape Petrel, Daption capense Southern Giant-Petrel, Macronectes giganteus Northern Giant-Petrel, Macronectes halli Southern Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialoides Atlantic Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialis Pacific Fulmar, Fulmarus rodgersii Kerguelen Petrel, Aphrodroma brevirostris Peruvian Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides garnotii Common Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides urinatrix South Georgia Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides georgicus Pelecanoidinae Magellanic Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides magellani Blue Petrel, Halobaena caerulea Fairy Prion, Pachyptila turtur ?Fulmar Prion, Pachyptila crassirostris Broad-billed Prion, Pachyptila vittata Salvin’s Prion, Pachyptila salvini Antarctic Prion, Pachyptila desolata ?Slender-billed Prion, Pachyptila belcheri Bonin Petrel, Pterodroma hypoleuca ?Gould’s Petrel, Pterodroma leucoptera ?Collared Petrel, Pterodroma brevipes Cook’s Petrel, Pterodroma cookii ?Masatierra Petrel / De Filippi’s Petrel, Pterodroma defilippiana Stejneger’s Petrel, Pterodroma longirostris ?Pycroft’s Petrel, Pterodroma pycrofti Soft-plumaged Petrel, Pterodroma mollis Gray-faced Petrel, Pterodroma gouldi Magenta Petrel, Pterodroma magentae ?Phoenix Petrel, Pterodroma alba Atlantic Petrel, Pterodroma incerta Great-winged Petrel, Pterodroma macroptera Pterodrominae White-headed Petrel, Pterodroma lessonii Black-capped Petrel, Pterodroma hasitata Bermuda Petrel / Cahow, Pterodroma cahow Zino’s Petrel / Madeira Petrel, Pterodroma madeira Desertas Petrel, Pterodroma -

The Dark Storm-Petrels of the Eastern North Pacific ~ Birding

BIRDING IN CALIFORNIA n California one has only to take a small boat a little ways out of Moss Landing David Ainley Ior Monterey—row one, even, as Rollo Beck, a giant in marine ornithology, did H.T. Harvey & Associates in the early years of the 20th century—to find oneself immersed in storm-petrels: 3150 Almaden Expressway - Suite 145 Ashy, Black, and occasional individuals of several other species. This scenario con- San Jose CA 95118 trasts greatly with the effort required to see storm-petrels in most other places on [email protected] the planet. On the North American East Coast where I began my days, storm- petrels are numbered—as they are in most places—among that almost-mythical group of birds which most of us only dream of seeing, and only after a day’s trip These bleak-looking desert islands are home out of harbor to the deep-water, pelagic habitat they call home. With this image to huge colonies of dark storm-petrels that probably total millions of birds—Leach’s, implanted deep in my psyche long ago, there is no way that I can tire of seeing Black, and Least in decreasing abundance. storm-petrels at sea, even having lived on the central California coast now for 30 Leach’s nests most commonly on the flatter and lower ground, where birds can dig bur- years and seeing the birds regularly. To me, the excitement of a deep-sea voyage— rows; Black nests most commonly on the rocky slopes, in crevices and burrows; Least nests and I’ve managed to make a few of these—is generated by the chance to be in the most commonly in scree and rock piles around “true” storm-petrel realm, where winds and huge waves remind us of why most the lower slopes.