Geographic Variation in Leach's Storm-Petrel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TREND NOTE Number 021, October 2012

SCOTTISH NATURAL HERITAGE TREND NOTE Number 021, October 2012 SEABIRDS IN SCOTLAND Prepared by Simon Foster and Sue Marrs of SNH Knowledge Information Management Unit using results from the Seabird Monitoring Programme and the Joint Nature Conservation Committee Scotland has internationally important populations of several seabirds. Their conservation is assisted through a network of designated sites. Figure 1 shows the distribution of the 50 Special Protection Areas (SPA) which have seabirds listed as a feature of interest. The map shows the widespread nature of the sites and the predominance of important seabird areas on the Northern Isles (Orkney and Shetland), where some of our largest seabird colonies are present. The most recent estimate of seabird populations was obtained from Birds of Scotland (Forrester et al., 2007). Table 1 shows the population levels for all seabirds regularly breeding in Scotland. Table 1: Population Estimates for Breeding Seabirds in Scotland. Figure 1: Special Protection Areas for Seabirds Breeding in Scotland. Species* Unit** Estimate Key Points Northern fulmar 486,000 AOS Manx shearwater 126,545 AOS Trends are described for 11 of the 24 European storm-petrel 31,570+ AOS species of seabirds breeding in Leach’s storm-petrel 48,057 AOS Scotland Northern gannet 182,511 AOS Great cormorant c. 3,600 AON Nine have shown sustained declines European shag 21,500-30,000 PAIRS over the past 20 years. Two have Arctic skua 2,100 AOT remained stable. Great skua 9,650 AOT The reasons for the declines are Black headed -

New Species Accepted –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Swinhoe’S Storm-Petrel (Oceanodroma Monorhis )

his is the 20th published report of the ABA Checklist Committee (hereafter, TCLC), covering the period July 2008– July 2009. There were no changes to commit - tee membership since our previous report (Pranty et al. 2008). Kevin Zimmer has been elected to serve his second term (to expire at the end of 2012), and Bill Pranty has been reelected to serve as Chair for a fourth year. During the preceding 13 months, the CLC final - ized votes on five species. Four species were accepted and added to the ABA Checklist , while one species was removed. The number of accepted species on the ABA Checklist is increased to 960. In January 2009, the seventh edition of the ABA Checklist (Pranty et al. 2009) was published. Each species is numbered from 1 (Black-bellied Whistling-Duck) to 957 (Eurasian Tree Sparrow); ancillary numbers will be inserted for all new species, and these numbers will be included in our annual reports. Production of the seventh edi - tion of the ABA Checklist occupied much of Pranty’s and Dunn’s time during the period, and this com - mitment helps to explain the relative paucity of votes during 2008–2009 compared to our other recent an - nual reports. New Species Accepted –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Swinhoe’s Storm-Petrel (Oceanodroma monorhis ). ABA CLC Record #2009-02. One individual, thought to be a juvenile in slightly worn plumage, in the At - lantic Ocean at 3 4°5 7’ N, 7 5°0 5’ W, approximately 65 kilometers east-southeast of Hatteras Inlet, Cape Hat - teras, North Carolina on 2 June 2008. -

Behavior and Attendance Patterns of the Fork-Tailed Storm-Petrel

BEHAVIOR AND ATTENDANCE PATTERNS OF THE FORK-TAILED STORM-PETREL THEODORE R. SIMONS Wildlife Science Group, Collegeof Forest Resources, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington 98195 USA ABSTRACT.--Behavior and attendance patterns of breeding Fork-tailed Storm-Petrels (Ocea- nodromafurcata) were monitored over two nesting seasonson the Barren Islands, Alaska. The asynchrony of egg laying and hatching shown by these birds apparently reflects the influence of severalfactors, including snow conditionson the breedinggrounds, egg neglectduring incubation, and food availability. Communication between breeding birds was characterized by auditory and tactile signals.Two distinct vocalizationswere identified, one of which appearsto be a sex-specific call given by males during pair formation. Generally, both adults were present in the burrow on the night of egg laying, and the male took the first incubation shift. Incubation shiftsranged from 1 to 5 days, with 2- and 3-day shifts being the most common. Growth parameters of the chicks, reproductive success, and breeding chronology varied considerably between years; this pre- sumably relates to a difference in conditions affecting the availability of food. Adults apparently responded to changes in food availability during incubation by altering their attendance patterns. When conditionswere good, incubation shifts were shorter, egg neglectwas reduced, and chicks were brooded longer and were fed more frequently. Adults assistedthe chick in emerging from the shell. Chicks became active late in the nestling stage and began to venture from the burrow severaldays prior to fledging. Adults continuedto visit the chick during that time but may have reducedthe amountof fooddelivered. Chicks exhibiteda distinctprefledging weight loss.Received 18 September1979, accepted26 July 1980. -

Copulation and Mate Guarding in the Northern Fulmar

COPULATION AND MATE GUARDING IN THE NORTHERN FULMAR SCOTT A. HATCH Museumof VertebrateZoology, University of California,Berkeley, California 94720 USA and AlaskaFish and WildlifeResearch Center, U.S. Fish and WildlifeService, 1011 East Tudor Road, Anchorage,Alaska 99503 USA• ABSTRACT.--Istudied the timing and frequency of copulation in mated pairs and the occurrenceof extra-paircopulation (EPC) among Northern Fulmars (Fulmarus glacialis) for 2 yr. Copulationpeaked 24 days before laying, a few daysbefore females departed on a prelaying exodus of about 3 weeks. I estimated that females were inseminated at least 34 times each season.A total of 44 EPC attemptswas seen,9 (20%)of which apparentlyresulted in insem- ination.Five successful EPCs were solicitated by femalesvisiting neighboring males. Multiple copulationsduring a singlemounting were rare within pairsbut occurredin nearly half of the successfulEPCs. Both sexesvisited neighborsduring the prelayingperiod, and males employed a specialbehavioral display to gain acceptanceby unattended females.Males investedtime in nest-siteattendance during the prelaying period to guard their matesand pursueEPC. However, the occurrenceof EPC in fulmars waslargely a matter of female choice. Received29 September1986, accepted 16 February1987. THEoccurrence and significanceof extra-pair Bjorkland and Westman 1983; Buitron 1983; copulation (EPC) in monogamousbirds has Birkhead et al. 1985). generated much interest and discussion(Glad- I attemptedto documentthe occurrenceand stone 1979; Oring 1982; Ford 1983; McKinney behavioral contextof extra-pair copulationand et al. 1983, 1984). Becausethe males of monog- mate guarding in a colonial seabird,the North- amous species typically make a large invest- ern Fulmar (Fulmarus glacialis). Fulmars are ment in the careof eggsand young, the costof among the longest-lived birds known, and fi- being cuckolded is high, as are the benefits to delity to the same mate and nest site between the successfulcuckolder. -

Tube-Nosed Seabirds) Unique Characteristics

PELAGIC SEABIRDS OF THE CALIFORNIA CURRENT SYSTEM & CORDELL BANK NATIONAL MARINE SANCTUARY Written by Carol A. Keiper August, 2008 Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary protects an area of 529 square miles in one of the most productive offshore regions in North America. The sanctuary is located approximately 43 nautical miles northwest of the Golden Gate Bridge, and San Francisco California. The prominent feature of the Sanctuary is a submerged granite bank 4.5 miles wide and 9.5 miles long, which lay submerged 115 feet below the ocean’s surface. This unique undersea topography, in combination with the nutrient-rich ocean conditions created by the physical process of upwelling, produces a lush feeding ground. for countless invertebrates, fishes (over 180 species), marine mammals (over 25 species), and seabirds (over 60 species). The undersea oasis of the Cordell Bank and surrounding waters teems with life and provides food for hundreds of thousands of seabirds that travel from the Farallon Islands and the Point Reyes peninsula or have migrated thousands of miles from Alaska, Hawaii, Australia, New Zealand, and South America. Cordell Bank is also known as the albatross capital of the Northern Hemisphere because numerous species visit these waters. The US National Marine Sanctuaries are administered and managed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) who work with the public and other partners to balance human use and enjoyment with long-term conservation. There are four major orders of seabirds: 1) Sphenisciformes – penguins 2) *Procellariformes – albatross, fulmars, shearwaters, petrels 3) Pelecaniformes – pelicans, boobies, cormorants, frigate birds 4) *Charadriiformes - Gulls, Terns, & Alcids *Orders presented in this seminar In general, seabirds have life histories characterized by low productivity, delayed maturity, and relatively high adult survival. -

Acoustic Attraction of Grey-Faced Petrels (Pterodroma Macroptera Gouldi) and Fluttering Shearwaters (Puffinus Gavia) to Young Nick’S Head, New Zealand

166 Notornis, 2010, Vol. 57: 166-168 0029-4470 © The Ornithological Society of New Zealand, Inc. SHORT NOTE Acoustic attraction of grey-faced petrels (Pterodroma macroptera gouldi) and fluttering shearwaters (Puffinus gavia) to Young Nick’s Head, New Zealand STEVE L. SAWYER* Ecoworks NZ Ltd, 369 Wharerata Road, RD1, Gisborne 4071, New Zealand SALLY R. FOGLE Ecoworks NZ Ltd, 369 Wharerata Road, RD1, Gisborne 4071, New Zealand Burrow-nesting and surface-nesting petrels colonies at sites following extirpation or at novel (Families Procellariidae, Hydrobatidae and nesting habitats, as the attraction of prospecting Oceanitidae) in New Zealand have been severely non-breeders to a novel site is unlikely and the affected by human colonisation, especially through probabilities of recolonisation further decrease the introduction of new predators (Taylor 2000). as the remaining populations diminish (Gummer Of the 41 extant species of petrel, shearwater 2003). and storm petrels in New Zealand, 35 species are Both active (translocation) and passive (social categorised as ‘threatened’ or ‘at risk’ with 3 species attraction) methods have been used in attempts to listed as nationally critical (Miskelly et al. 2008). establish or restore petrel colonies (e.g. Miskelly In conjunction with habitat protection, habitat & Taylor 2004; Podolsky & Kress 1992). Methods enhancement and predator control, the restoration for the translocation of petrel chicks to new colony of historic colonies or the attraction of petrels to sites are now fairly well established, with fledging new sites is recognised as important for achieving rates of 100% achievable, however, the return of conservation and species recovery objectives translocated chicks to release sites is still awaiting (Aikman et al. -

The Rise and Fall of Bulwer's Petrel

A paper from the British Ornithologists’ Union Records Committee The rise and fall of Bulwer’s Petrel Andrew H. J. Harrop ABSTRACT This short paper examines two recent reviews of records of Bulwer’s Petrel Bulweria bulwerii in Britain by BOURC. Four records were assessed, including three specimen records from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and a modern-day sighting from Cumbria. None was found acceptable, and the reasons are discussed here. ulwer’s Petrel Bulweria bulwerii was By the time The Handbook was published, seven named after Rev. James Bulwer, an records were listed for Britain, all in England Bamateur Norfolk collector, naturalist and (Witherby et al. 1940), and these were repeated conchologist, who first collected it in Madeira, in Bannerman’s The Birds of the British Isles probably in 1825 during a short expedition to (1959). Of these seven, four (all from Sussex, Deserta Grande (Mearns & Mearns 1988). It between 1904 and 1914) were subsequently was first described by Sir William Jardine and rejected as ‘Hastings Rarities’ (Nicholson & Fer- Prideaux John Selby, in Illustrations of guson-Lees 1962; see plate 380) and a fifth, said Ornithology in 1828 (Jardine & Selby 1828). The to have been picked up at Beachy Head, Sussex, species has had a turbulent history as a British by an unnamed person on 3rd February 1903, bird. This paper provides a brief summary of escaped this fate only because it occurred records in the British ornithological literature, outside the area used to define ‘Hastings’ presents the results of two BOURC reviews, and records (Bourne 1967). -

2010 FINAL MAMU Reportav

Summary of 2010 Marbled Murrelet Monitoring Surveys In the Santa Cruz Mountains Prepared For: Department of Parks and Recreation Santa Cruz District 303 Big Trees Park Road Felton CA, 95018 Prepared By: Brian Shaw Klamath Wildlife Resources 1760 Kenyon Drive Redding, CA 96001 12/31/2010 Edited for clarity, organization and content by: Portia Halbert ES for California State Parks 12/19/2014 INTRODUCTION This report covers the results of Marbled Murrelet (Brachyramphus marmoratus) monitoring surveys completed in 2010 for the Santa Cruz District of California State Parks, and is the first of a three-year monitoring effort for the seabird. The surveys took place at Big Basin Redwoods State Park, Portola Redwoods State Park, Butano State Park and San Mateo County Memorial Park. These surveys are carried out in support of and to follow-up data gathered by previous similar studies completed in the Santa Cruz Mountains from years back as far as 1992. It also continues an ongoing effort to study murrelet populations after the Command oil spill that occurred in 1988. METHODOLOGY In previous years, California Department of Fish and Game (DFG) has funded this work; at Portola and Big Basin since 1992 and 1995. At Portola, monitoring years included 1992- 1995, 1998, as well as in 2001-2003 and included only one murrelet observation station. The study has been carried out at Big Basin at five survey stations over the years of 1995-1996, 1998, and 2001-2003. During the 1995-1996, and 1998 the monitoring at Big Basin consisted of five surveys at each station during the protocol period. -

SEAPOP Studies in the Lofoten and Barents Sea Area in 2006

249 SEAPOP studies in the Lofoten and Barents Sea area in 2006 Tycho Anker-Nilssen Robert T. Barrett Jan Ove Bustnes Kjell Einar Erikstad Per Fauchald Svein-Håkon Lorentsen Harald Steen Hallvard Strøm Geir Helge Systad Torkild Tveraa NINA Publications NINA Report (NINA Rapport) This is a new, electronic series beginning in 2005, which replaces the earlier series NINA commissioned reports and NINA project reports. This will be NINA’s usual form of reporting completed research, monitoring or review work to clients. In addition, the series will include much of the institute’s other reporting, for example from seminars and conferences, results of internal research and review work and literature studies, etc. NINA report may also be issued in a second language where appropriate. NINA Special Report (NINA Temahefte) As the name suggests, special reports deal with special subjects. Special reports are produced as required and the series ranges widely: from systematic identification keys to information on important problem areas in society. NINA special reports are usually given a popular scientific form with more weight on illustrations than a NINA report. NINA Factsheet (NINA Fakta) Factsheets have as their goal to make NINA’s research results quickly and easily accessible to the general public. The are sent to the press, civil society organisations, nature management at all levels, politicians, and other special interests. Fact sheets give a short presentation of some of our most important research themes. Other publishing In addition to reporting in NINA’s own series, the institute’s employees publish a large proportion of their scientific results in international journals, popular science books and magazines. -

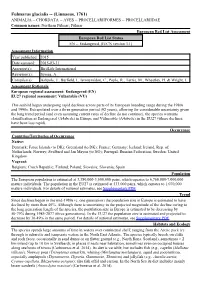

Fulmarus Glacialis

Fulmarus glacialis -- (Linnaeus, 1761) ANIMALIA -- CHORDATA -- AVES -- PROCELLARIIFORMES -- PROCELLARIIDAE Common names: Northern Fulmar; Fulmar European Red List Assessment European Red List Status EN -- Endangered, (IUCN version 3.1) Assessment Information Year published: 2015 Date assessed: 2015-03-31 Assessor(s): BirdLife International Reviewer(s): Symes, A. Compiler(s): Ashpole, J., Burfield, I., Ieronymidou, C., Pople, R., Tarzia, M., Wheatley, H. & Wright, L. Assessment Rationale European regional assessment: Endangered (EN) EU27 regional assessment: Vulnerable (VU) This seabird began undergoing rapid declines across parts of its European breeding range during the 1980s and 1990s. Extrapolated over a three generation period (92 years), allowing for considerable uncertainty given the long trend period (and even assuming current rates of decline do not continue), the species warrants classification as Endangered (A4abcde) in Europe and Vulnerable (A4abcde) in the EU27 (where declines have been less rapid). Occurrence Countries/Territories of Occurrence Native: Denmark; Faroe Islands (to DK); Greenland (to DK); France; Germany; Iceland; Ireland, Rep. of; Netherlands; Norway; Svalbard and Jan Mayen (to NO); Portugal; Russian Federation; Sweden; United Kingdom Vagrant: Belgium; Czech Republic; Finland; Poland; Slovakia; Slovenia; Spain Population The European population is estimated at 3,380,000-3,500,000 pairs, which equates to 6,760,000-7,000,000 mature individuals. The population in the EU27 is estimated at 533,000 pairs, which equates to 1,070,000 mature individuals. For details of national estimates, see Supplementary PDF. Trend Since declines began in the mid-1980s (c. one generation) the population size in Europe is estimated to have declined by more than 40%. -

Management Plan for Antarctic Specially Protected Area No

Measure 2 (2005) Annex E Management Plan for Antarctic Specially Protected Area No. 120 POINTE-GÉOLOGIE ARCHIPELAGO, TERRE ADÉLIE Jean Rostand, Le Mauguen (former Alexis Carrel), Lamarck and Claude Bernard Islands, The Good Doctor’s Nunatak and breeding site of Emperor Penguins 1. Description of Values to be Protected In 1995, four islands, a nunatak and a breeding ground for emperor penguins were classified as an Antarctic Specially Protected Area (Measure 3 (1995), XIX ATCM, Seoul) because they were a representative example of terrestrial Antarctic ecosystems from a biological, geological and aesthetics perspective. A species of marine mammal, the Weddell seal (Leptonychotes weddelli) and various species of birds breed in the area: emperor penguin (Aptenodytes forsteri); Antarctic skua (Catharacta maccormicki); Adélie penguins (Pygoscelis adeliae); Wilson’s petrel (Oceanites oceanicus); giant petrel (Macronectes giganteus); snow petrel (Pagodrama nivea), cape petrel (Daption capense). Well-marked hills display asymmetrical transverse profiles with gently dipping northern slopes compared to the steeper southern ones. The terrain is affected by numerous cracks and fractures leading to very rough surfaces. The basement rocks consist mainly of sillimanite, cordierite and garnet-rich gneisses which are intruded by abundant dikes of pink anatexites. The lowest parts of the islands are covered by morainic boulders with a heterogenous granulometry (from a few cm to more than a m across). Long-term research and monitoring programs of birds and marine mammals have been going on for a long time already (since 1952 or 1964 according to the species). A database implemented in 1981 is directed by the Centre d'Etudes Biologiques de Chize (CEBC-CNRS). -

NORTHERN FULMAR Fulmarus Glacialis Non-Breeding Visitor, Occasional Winterer F.G

NORTHERN FULMAR Fulmarus glacialis non-breeding visitor, occasional winterer F.g. rodgersii Northern Fulmars breed throughout the Holarctic and winter irregularly south to temperate Pacific and Atlantic waters (Dement'ev and Gladkov 1951a, Cramp and Simmons 1977, Harrison 1983, AOU 1998). They occasionally reach the Hawaiian region in Nov-Mar, with most records being of birds found weak or dead on shore. In the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, remains of 18 individuals have been found (Clapp and Woodward 1968, Woodward 1972, Zeillemaker 1976), on Kure (4, 1976- 1978; USNM 498110-112, 492919; HRBP 0017, 0040); Midway (9, 1962-1996; e.g., USNM 478860, 498113-114; BPBM 178503, 183500, 184419); Pearl and Hermes Reef 6 Apr 1976; and French Frigate 25 Jun 1923 (USNM 489327). Many specimens were old and dry, with fresher ones being collected between late Dec and mid Mar. Individuals were also observed from shore at Midway 8-10 Dec 1959 and 16 Dec 1962 (Fisher 1965); a light-morph bird reported from Midway 5 Sep 2007 would be very early and may have been of a gull. In the Southeastern Hawaiian Islands, one found alive but with a broken neck on Larson's Beach, Kaua'i, 3 Mar 2004 was photographed (HRBP 5029) and later died (BPBM 185188). On O'ahu, weak or dead birds were found on Waimanalo Beach 17 Feb 1959 (King 1959a); Kailua Beach 18 Nov 1983 (USNM 614986), 5 Dec 1987 (HRBP 0725-0727; BPBM 175993), 15 Jan 1989 (HRBP 0914-0915; BPBM 177891), and 17 Nov 2008 (HRBP 5443-5444; BPBM); and in Honolulu 23 March 1998 (BPBM 184115).