{Replace with the Title of Your Dissertation}

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Harem 19Th-20Th Centuries”

Pt.II: Colonialism, Nationalism, the Harem 19th-20th centuries” Week 11: Nov. 27-9; Dec. 2 “Northern Nigeria: from Caliphate to Colony” Nigeria: 19th-20th C. • Early 19th C. Jihad established Sokoto Caliphate: • Uthman dan Fodio • Born to scholarly family (c.1750) • Followed conservative Saharan brotherhood (Qadiriyya) Northern Nigeria: 19th-20th C. Nigeria: 19th-20th C. • 1790s – 1804: growing reputation as teacher • Preaching against Hausa Islam: state we left in discussion of Kano Palace18th c. (Nast) • ‘corruption’: illegal imposition various taxes • ‘paganism’: continued practice ‘pre-Islamic’ rituals (especially Bori spirit cult) • Charged political opponent, Emir of Gobir as openly supporting: first ‘target’ of jihad Nigeria: 19th-20th C. • 1804: beginning of jihad • Long documented correspondence/debate between them • Emir of Gobir did not accept that he was ‘bad Muslim’ who needed to ‘convert’ – dan Fodio ‘disagreed’ • Declared ‘Holy War’ Nigeria: 19th-20th C. Nigeria: 19th-20th C. • Drew in surrounding regions: why attracted? • marginalization vis-à-vis central Hausa provinces • exploited by excessive taxation • attraction of dan Fodio’s charisma, genuine religious fervour Nigeria: 19th-20th C. • 1817, Uthman dan Fodio died: • Muhamed Bello (son) took over as ‘caliph’ • nature of jihad changed fundamentally: became one of ‘the heart and mind’ • ‘conquest’ only established fragile boundaries of state • did not create the Islamic regime envisaged by dan Fodio Nigeria: 19th-20th C. • New ‘Islamic state’ carved out of pre-existing Muslim society: needed full legitimization • Key ‘tool’ to shaping new society -- ‘educating people to understand the Revolution’ -- was education Nigeria: 19th-20th C. Nana Asma’u (1793 – 1864): - educated daughter of Uthman dan Fodio - fluent in Arabic, Fulfulbe, Hausa, Tamechek [Tuareg] - sister Mohamed Bello Nigeria: 19th-20th C. -

Africans: the HISTORY of a CONTINENT, Second Edition

P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 This page intentionally left blank ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 africans, second edition Inavast and all-embracing study of Africa, from the origins of mankind to the AIDS epidemic, John Iliffe refocuses its history on the peopling of an environmentally hostilecontinent.Africanshavebeenpioneersstrugglingagainstdiseaseandnature, and their social, economic, and political institutions have been designed to ensure their survival. In the context of medical progress and other twentieth-century innovations, however, the same institutions have bred the most rapid population growth the world has ever seen. The history of the continent is thus a single story binding living Africans to their earliest human ancestors. John Iliffe was Professor of African History at the University of Cambridge and is a Fellow of St. John’s College. He is the author of several books on Africa, including Amodern history of Tanganyika and The African poor: A history,which was awarded the Herskovits Prize of the African Studies Association of the United States. Both books were published by Cambridge University Press. i P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 african studies The African Studies Series,founded in 1968 in collaboration with the African Studies Centre of the University of Cambridge, is a prestigious series of monographs and general studies on Africa covering history, anthropology, economics, sociology, and political science. -

Legacies of Colonialism and Islam for Hausa Women: an Historical Analysis, 1804-1960

Legacies of Colonialism and Islam for Hausa Women: An Historical Analysis, 1804-1960 by Kari Bergstrom Michigan State University Winner of the Rita S. Gallin Award for the Best Graduate Student Paper in Women and International Development Working Paper #276 October 2002 Abstract This paper looks at the effects of Islamization and colonialism on women in Hausaland. Beginning with the jihad and subsequent Islamic government of ‘dan Fodio, I examine the changes impacting Hausa women in and outside of the Caliphate he established. Women inside of the Caliphate were increasingly pushed out of public life and relegated to the domestic space. Islamic law was widely established, and large-scale slave production became key to the economy of the Caliphate. In contrast, Hausa women outside of the Caliphate were better able to maintain historical positions of authority in political and religious realms. As the French and British colonized Hausaland, the partition they made corresponded roughly with those Hausas inside and outside of the Caliphate. The British colonized the Caliphate through a system of indirect rule, which reinforced many of the Caliphate’s ways of governance. The British did, however, abolish slavery and impose a new legal system, both of which had significant effects on Hausa women in Nigeria. The French colonized the northern Hausa kingdoms, which had resisted the Caliphate’s rule. Through patriarchal French colonial policies, Hausa women in Niger found they could no longer exercise the political and religious authority that they historically had held. The literature on Hausa women in Niger is considerably less well developed than it is for Hausa women in Nigeria. -

The Fulani Jihad & Its Implication for National Integration

An International Multidisciplinary Journal, Ethiopia Vol. 5 (5), Serial No. 22, October, 2011 ISSN 1994-9057 (Print) ISSN 2070--0083 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/afrrev.v5i5.1 The Fulani Jihad and its Implication for National Integration and Development in Nigeria (Pp. 1-12) Aremu, Johnson Olaosebikan - Department of History and International Studies, University of Ado-Ekiti, Ekiti State, Nigeria. E-mail Address: [email protected] ℡+2348032477652 Abstract The Fulani Jihad (1804-1810) led by Shehu, Uthman Dan Fodio was successfully prosecuted against the established Hausa dynasty in Northern Nigeria. It led to the emergence of a theocratic state, the Sokoto Caliphate, which was administered largely as a federation, due to its wide expanse and diverse composition of its people. The causes, management and impact of the Jihad as well as important lessons for national integration and development in contemporary Nigerian political life form the basic themes of this paper. Key words: Jihad, Integration, Theocracy, National Development, Caliphate Introduction The Fulani Jihad (1804-1810), had its heart and beginning in Gobir. It should be noted that the very essence of the Jihad against established Hausa dynasty was in itself a revolution in relationship between the Hausa and the Fulanis. It is informative to note that Islam was introduced into Hausa land about the 14 th century by foreign Mallams and merchants, such as Wagara Arabs and the Fulanis (Adeleye 1971:560; Afe 2003:23; Hill,2009:8). The latter group (Fulani’s) was said to have migrated over the centuries from Futa-Toro area Copyright © IAARR 2011: www.afrrevjo.com 1 Indexed African Journals Online: www.ajol.info Vol. -

Young Achievers 2015

COMMONWEALTH YOUNG ACHIEVERS 2015 COMMONWEALTH YOUNG ACHIEVERS 2015 S R CHIEVE A G N OU 2015 Y TH L COMMONWEA TEAM OF THE COMMONWEALTH YOUNGCOMMONWEA LTH ACHIEVERS BOOKYOUNG ACHIEVERS 2015 Editorial Team Ahmed Adamu (Nigeria) Tilan M Wijesooriya (Sri Lanka) Ziggy Adam (Seychelles) Jerome Cowans (Jamaica) Melissa Bryant (St. Kitts and Nevis) Layout & Design Abdul Basith (Sri Lanka) © Commonwealth Youth Council, United Kingdom, 2015 Published by: Commonwealth Youth Council, United Kingdom Cover design: Abdul Basith (Sri Lanka) & Akiel Surajdeen (Sri Lanka) Permission is required to reproduce any part of this book CONTENTS Chapter 01 Introduction Page 1 • Preamble • Acknowledgement • Foreword Message from the Chairperson – Commonwealth Youth Council (CYC) • About the CYC • Synopses of CYC Executives Chapter 02 Commonwealth Young Achievers Page 21 • Africa • Asia • Caribbean and Americas • Europe • Pacific TH L COMMONWEA Chapter 03 Youth Development Perspectives Page 279 • Generating Positive Change through Youth 2015 S R CHIEVE A G N OU Y Volunteerism • When people talk, great things happen: The Role of Youth in Peace-building and Social Cohesion • Why Africa’s Youths Are So Passionate about Change • Stop washing your hands of young people…Time for action: Youth and Politics • Youth Entrepreneurship and Overcoming Youth Unemployment • Trialling Youth Ideas on Civic Participation • Youth participation in environment protection Chapter 04 Conclusion and Way Forward Page 323 2015 S TH L R CHIEVE COMMONWEA A G N OU Y OUNG ACHIEVERS Y 2015 COMMONWEALTH COMMONWEALTH YOUNG ACHIEVERS 2015 Y OU N G A COMMONWEA CHIEVE R L TH S 2015 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION COMMONWEALTH 2015 YOUNG ACHIEVERS 2015 Years of Vigour and Freshness Ocean of Potentials Unending Efforts and Enthusiasm Tears of Hardships Hope for a Better World PREAMBLE Years of vigour and freshness, Ocean of potentials, Unending efforts and enthusiasm, Tears of hardships, Hope for a better world (YOUTH). -

Soil Survey Papers No. 5

Soil Survey Papers No. 5 ANCIENTDUNE FIELDS AND FLUVIATILE DEPOSITS IN THE RIMA-SOKOTO RIVER BASIN (N.W. NIGERIA) W. G. Sombroek and I. S. Zonneveld Netherlands Soil Survey Institute, Wageningen A/Gr /3TI.O' SOIL SURVEY PAPERS No. 5 ANCIENT DUNE FIELDS AND FLUVIATILE DEPOSITS IN THE RIMA-SOKOTO RIVER BASIN (N.W. NIGERIA) Geomorphologie phenomena in relation to Quaternary changes in climate at the southern edge of the Sahara W. G. Sombroek and I. S. Zonneveld Scanned from original by ISRIC - World Soil Information, as ICSU ! World Data Centre for Soils. The purpose is to make a safe depository for endangered documents and to make the accrued ! information available for consultation, following Fair Use ' Guidelines. Every effort is taken to respect Copyright of the materials within the archives where the identification of the j Copyright holder is clear and, where feasible, to contact the i originators. For questions please contact soil.isricOwur.nl \ indicating the item reference number concerned. ! J SOIL SURVEY INSTITUTE, WAGENINGEN, THE NETHERLANDS — 1971 3TV9 Dr. I. S. Zonneveld was chief of the soils and land evaluation section of the Sokoto valley project and is at present Ass. Professor in Ecology at the International Institute for Aerial Survey and Earth Science (ITC) at Enschede, The Netherlands (P.O. Box 6, Enschede). Dr. W. G. Sombroek was a member of the same soils and evaluation section and is at present Project Manager of the Kenya Soil Survey Project, which is being supported by the Dutch Directorate for International Technical Assistance (P.O. Box 30028, Nairobi). The opinions and conclusions expressed in this publication are the authors' own personal views, and may not be taken as reflecting the official opinion or policies of either the Nigerian Authorities or the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. -

Influence of Arabic Poetry on the Composition and Dating of Fulfulde Jihad Poetry in Yola* (Nigeria)

INFLUENCE OF ARABIC POETRY ON THE COMPOSITION AND DATING OF FULFULDE JIHAD POETRY IN YOLA* (NIGERIA) Anneke Breedveld** 1. Introduction One of the significant contexts of use of Arabic script in Africa is the large amount of manuscripts in Fulfulde, inspired especially by Sheehu Usman dan Fodio. The writings of this pivotal political and religious leader and his contemporaries have been revered by his followers, and thus ample numbers have survived until the present day. Being Muslims and inspired by Arabic poetry, Usman dan Fodio’s contemporaries have used the Arabic script and metre to write up their compositions in various languages. The power of the Fulbe states in West Africa was closely associated with the Fulbe’s ‘ownership’ of Islam. Their aversion to the colonial powers who undermined their ruling position has since also led to a massive rejection of Western and Christian education by successive generations of Fulbe (Breedveld 2006; Regis 1997). Most Muslim children do learn to read and write Arabic in the Qurʾanic schools, resulting in widespread use of the Arabic script in Fulbe societies until today. The aim of this paper is to present initial results from the investigation of the jihad poetry composed in Fulfulde which is now available in Yola, Nigeria, and is, for the purpose of this paper dubbed the Yola collection. This collection contains 93 manuscripts of copied Fulfulde poems by Usman dan Fodio and his contemporaries and is at present privately owned by a family (see below). First, the present paper gives a brief introduction to the main poet, Usman dan Fodio, and his contemporaries are named. -

Federal Republic of Nigeria - Official Gazette

Federal Republic of Nigeria - Official Gazette No. 47 Lagos ~ 29th September, 1977 Vol. 64 CONTENTS Page Page Movements of Officers ” ; 1444-55 “Asaba Inland Postal Agency—Opening of .. 1471 Loss of Local Purchase Orders oe .« 1471 Ministry of Defence—Nigerian Army— Commissions . 1455-61 Loss of Treasury Receipt Book ‘6 1471 Ministry of Defence—Nigerian Army— Loss of Cheque . 1471 Compulsory Retirement... 1462 Ministry of Education—Examination in Trade Dispute between Marine’ Drilling , Law, Civil Service Rules, Financial Regu- and Constructions Workers’ Union of lations, Police Orders and Instructions Nigeria and Zapata Marine Service and. Ppractical Palice Work-——December (Nigeria) Limited .e .. 1462. 1977 Series +. 1471-72 -Trade Dispute between Marine Drilling Oyo State of Nigeria Public Service and Construction Workers? Unions of Competition for Entry into the Admini- Nigeria and Transworld Drilling Com-- strative and Special Departmental Cadres pay (Nigeria) Limited . 1462-63 in 1978 , . 1472-73 Constituent Assembly—Elected Candi. Vacancies .- 1473-74 ; dates ~ -» ° 1463-69 Customs and Excise—Dieposal of Un- . Land required for the Service of the _ Claimed Goods at Koko Port o. 1474 Federal Military Government 1469-70 Termination of Oil Prospecting Licences 1470 InpEx To LecaL Notice in SupPLEMENT Royalty on Thorium and Zircon Ores . (1470 Provisional Royalty on Tantalite .. -- 1470 L.N. No. Short Title Page Provisional Royalty on Columbite 1470 53 Currency Offences Tribunal (Proce- Nkpat Enin Postal Agency--Opening of 1471 dure) (Amendment) Rules 1977... B241 1444 - OFFICIAL GAZETTE No. 47, Vol. 64 Government Notice No. 1235 NEW APPOINTMENTS AND OTHER STAFF CHANGES - The following are notified for general information _ NEW APPOINTMENTS Department ”Name ” Appointment- Date of Appointment Customs and Excise A j ~Clerical Assistant 1-2~73 ‘ ‘Adewoyin,f OfficerofCustoms and Excise 25-8-75 Akan: Cleri . -

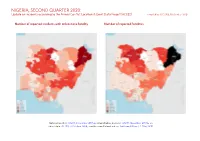

NIGERIA, SECOND QUARTER 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 30 October 2020

NIGERIA, SECOND QUARTER 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 30 October 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; in- cident data: ACLED, 3 October 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 NIGERIA, SECOND QUARTER 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 30 OCTOBER 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Violence against civilians 356 233 825 Conflict incidents by category 2 Battles 246 200 1257 Development of conflict incidents from June 2018 to June 2020 2 Protests 141 1 1 Explosions / Remote Methodology 3 77 67 855 violence Conflict incidents per province 4 Riots 75 26 42 Strategic developments 18 0 0 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 913 527 2980 Disclaimer 8 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 3 October 2020). Development of conflict incidents from June 2018 to June 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 3 October 2020). 2 NIGERIA, SECOND QUARTER 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 30 OCTOBER 2020 Methodology on what level of detail is reported. Thus, towns may represent the wider region in which an incident occured, or the provincial capital may be used if only the province The data used in this report was collected by the Armed Conflict Location & Event is known. -

Al-Mahram Journal, Vol. IX (English) 101 101 HERITAGE

Al-Mahram Journal, vol. IX (English) HERITAGE MANAGEMENT IN THE SOKOTO RIMA BASIN: A CASE STUDY OF ALKALAWA IN SABON BIRNI LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA OF SOKOTO STATE. Isa Muhammad Abstract Alkalawa is an abandoned settlement site, located ten kilometers away from SabonBirni Local Government Area Sokoto State Nigeria. It has got some archaeological features like; grave yard, dye pits, ruins of defensive wall, historical manuscript which speak a lot about the heritage of Gobir people who settled in this site. The site is currently enlisted as one of the tourist site in Sokoto State because of its archaeological potentials. The Ministry of Arts and Tourism started a site Museum which is uncompleted and It also attract people from within and outside Nigeria who come to seek spiritual blessing from the grave of Bawa Jan Gwarzo and other rulers of Gobir Kingdom. Despite these potentials the site is currently managed by the inhabitant of the present day Alkalawa village. Little or no support is coming from the State Government in safeguarding these archaeological resources and the site is under threat due to intensive farming and desertification. This paper attempts to suggest ways towards managing and protecting this historical site for the purpose of education, tourism and economic activities. 101 101 Al-Mahram Journal, vol. IX (English) Keywords: Heritage Management, Sokoto Rima and Archaeological potentials. Introduction Alkalawa is located onlatitude 130 36’ 47” N andlongitude 06015’ 36” E and inSabonBirni Local Government Area of Sokoto State.The early settlers in Alkalawa were said to be Gobirawawho were said to have been Kipiti (Copts) from Misra (Egypt) (Na-dama 1977:289). -

Alternative Dispute Resolution – the Biu Emirate Mediation Centre

January 2018 Newsletter - Enhancing State and Community Level Conflict Management Capability in North Eastern Nigeria This is a 4-year programme that will enhance state and community level conflict management capability in order to prevent the escalation of conflict into violence across the three North East States of Nigeria – Adamawa, Borno and Yobe. Key Activities – January 2018 Alternative Dispute Resolution in Action – Borno State Traditional Ruler Training – Wives and Scribes/Record Keeping Systems Policy Dialogue Forum Meetings – Yobe and Borno States Continued Community Peace and Safety Platform (CPSPs) Meetings Alternative Dispute Resolution – The Biu Emirate Mediation Centre “Following the recent training we received from Green Horizon Limited under the European Union funded MCN Programme on Alternative Dispute Resolution, which took place in Biu, His Royal Highness the Emir of Biu, Alh. Umar Mustapha Aliyu, was briefed by the facilitators during their visit to the palace. Immediately after the visit, the Emir of Biu on 15 January 2018 established an office known as Dakin Sulhu (Mediation Centre). Mediation commenced at the Centre on 20 January 2018. So far we have mediated and resolved seven cases related to land, community leadership and family issue. A very important one is a case of mediation that settled the difference between two community leaders, Mal Kawo and Mal Magaji. Both of them had been contesting for leadership in their community and had been in dispute for the past 9 years, not even talking to each other. But with the intervention of the Dakin Sulhu, the dispute was laid to rest, and now they live amicably with each other.” Zannan Sulhu of Biu Emirate, head of Biu Emirate Mediation Centre (Dakin Sulhu) 1 Community Leaders shaking hands shortly after a 9-year old quarrel between them was settled at the Dakin Sulhu (Biu Emirate Mediation Centre). -

National Assembly 1780 2013 Appropriation Federal Government of Nigeria 2013 Budget Summary Ministry of Science & Technology

FEDERAL GOVERNMENT OF NIGERIA 2013 BUDGET SUMMARY MINISTRY OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY TOTAL OVERHEAD CODE TOTAL PERSONNEL TOTAL RECURRENT TOTAL CAPITAL TOTAL ALLOCATION COST MDA COST =N= =N= =N= =N= =N= 0228001001 MAIN MINISTRY 604,970,481 375,467,963 980,438,444 236,950,182 1,217,388,626 NATIONAL AGENCY FOR SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING 0228002001 INFRASTRUCTURE (NASENI), ABUJA 653,790,495 137,856,234 791,646,729 698,112,110 1,489,758,839 0228003001 SHEDA SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY COMPLEX - ABUJA 359,567,945 101,617,028 461,184,973 361,098,088 822,283,061 0228004001 NIGERIA NATURAL MEDICINE DEVELOPMENT AGENCY 185,262,269 99,109,980 284,372,249 112,387,108 396,759,357 NATIONAL SPACE RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT AGENCY - 0228005001 ABUJA 1,355,563,854 265,002,507 1,620,566,361 2,282,503,467 3,903,069,828 0228006001 COOPERATIVE INFORMATION NETWORK 394,221,969 26,694,508 420,916,477 20,000,000 440,916,477 NATIONAL BIOTECHNOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENT AGENCY - 0228008001 ABUJA 982,301,937 165,541,114 1,147,843,051 944,324,115 2,092,167,166 BOARD FOR TECHNOLOGY BUSINESS INCUBATOR CENTRE - 0228009001 ABUJA 178,581,519 107,838,350 286,419,869 351,410,244 637,830,113 0228010001 TECHNOLOGY BUSINESS INCUBATOR CENTRE - AGEGE 72,328,029 19,476,378 91,804,407 25,000,000 116,804,407 0228011001 TECHNOLOGY BUSINESS INCUBATOR CENTRE - ABA 50,377,617 11,815,480 62,193,097 - 62,193,097 0228012001 TECHNOLOGY BUSINESS INCUBATOR CENTRE - KANO 60,891,201 9,901,235 70,792,436 - 70,792,436 0228013001 TECHNOLOGY BUSINESS INCUBATOR CENTRE - NNEWI 41,690,557 10,535,472 52,226,029 - 52,226,029