Development of Writing in a Bilingual Program. Final Report. Volumes 1 and 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unicode Request for Cyrillic Modifier Letters Superscript Modifiers

Unicode request for Cyrillic modifier letters L2/21-107 Kirk Miller, [email protected] 2021 June 07 This is a request for spacing superscript and subscript Cyrillic characters. It has been favorably reviewed by Sebastian Kempgen (University of Bamberg) and others at the Commission for Computer Supported Processing of Medieval Slavonic Manuscripts and Early Printed Books. Cyrillic-based phonetic transcription uses superscript modifier letters in a manner analogous to the IPA. This convention is widespread, found in both academic publication and standard dictionaries. Transcription of pronunciations into Cyrillic is the norm for monolingual dictionaries, and Cyrillic rather than IPA is often found in linguistic descriptions as well, as seen in the illustrations below for Slavic dialectology, Yugur (Yellow Uyghur) and Evenki. The Great Russian Encyclopedia states that Cyrillic notation is more common in Russian studies than is IPA (‘Transkripcija’, Bol’šaja rossijskaja ènciplopedija, Russian Ministry of Culture, 2005–2019). Unicode currently encodes only three modifier Cyrillic letters: U+A69C ⟨ꚜ⟩ and U+A69D ⟨ꚝ⟩, intended for descriptions of Baltic languages in Latin script but ubiquitous for Slavic languages in Cyrillic script, and U+1D78 ⟨ᵸ⟩, used for nasalized vowels, for example in descriptions of Chechen. The requested spacing modifier letters cannot be substituted by the encoded combining diacritics because (a) some authors contrast them, and (b) they themselves need to be able to take combining diacritics, including diacritics that go under the modifier letter, as in ⟨ᶟ̭̈⟩BA . (See next section and e.g. Figure 18. ) In addition, some linguists make a distinction between spacing superscript letters, used for phonetic detail as in the IPA tradition, and spacing subscript letters, used to denote phonological concepts such as archiphonemes. -

Girl Names Registered in 1996

Baby Girl Names Registered in 1996 # Baby Girl Names # Baby Girl Names # Baby Girl Names 1 Aaliyah 1 Aiesha 1 Aleeta 1 Aamino 2 Aileen 1 Aleigha 1 Aamna 1 Ailish 2 Aleksandra 1 Aanchal 1 Ailsa 3 Alena 2 Aaryn 4 Aimee 1 Alesha 1 Aashna 1Ainslay 1 Alesia 5 Abbey 1Ainsleigh 1 Alesian 1 Abbi 4Ainsley 6 Alessandra 3 Abbie 1 Airianna 1 Alessia 2 Abbigail 1Airyn 1 Aleta 19 Abby 4 Aisha 5 Alex 1 Abear 1 Aishling 25 Alexa 1 Abena 6 Aislinn 1 Alexander 1 Abigael 1 Aiyana-Marie 128 Alexandra 32 Abigail 2Aja 2 Alexandrea 5 Abigayle 1 Ajdina 29 Alexandria 2 Abir 1 Ajsha 5 Alexia 1 Abrianna 1 Akasha 49 Alexis 1 Abrinna 1Akayla 1 Alexsandra 1 Abyen 2Akaysha 1 Alexus 1 Abygail 1Akelyn 2 Ali 2 Acacia 1 Akosua 7 Alia 1 Accacca 1 Aksana 1 Aliah 1 Ada 1 Akshpreet 1 Alice 1 Adalaine 1 Alabama 38 Alicia 1 Adan 2 Alaina 1 Alicja 1 Adanna 1 Alainah 1 Alicyn 1 Adara 20 Alana 4 Alida 1 Adarah 1 Alanah 2 Aliesha 1 Addisyn 1 Alanda 1 Alifa 1 Adele 1 Alandra 2 Alina 2 Adelle 12 Alanna 1 Aline 1 Adetola 6 Alannah 1 Alinna 1 Adrey 2 Alannis 4 Alisa 1 Adria 1Alara 1 Alisan 9 Adriana 1 Alasha 1 Alisar 6 Adrianna 2 Alaura 23 Alisha 1 Adrianne 1 Alaxandria 2 Alishia 1 Adrien 1 Alayna 1 Alisia 9 Adrienne 1 Alaynna 23 Alison 1 Aerial 1 Alayssia 9 Alissa 1 Aeriel 1 Alberta 1 Alissah 1 Afrika 1 Albertina 1 Alita 4 Aganetha 1 Alea 3 Alix 4 Agatha 2 Aleah 1 Alixandra 2 Agnes 4 Aleasha 4 Aliya 1 Ahmarie 1 Aleashea 1 Aliza 1 Ahnika 7Alecia 1 Allana 2 Aidan 2 Aleena 1 Allannha 1 Aiden 1 Aleeshya 1 Alleah Baby Girl Names Registered in 1996 Page 2 of 28 January, 2006 # Baby Girl Names -

Christina Yahn William Yahn Louise A. Yeaton Charles Ylonen -Z- Joyce L

1 Care Dimensions Tree of Lights 2019 Honor Roll Book 2 -A- Phyllis Abare Sidney Abare Walter L. Abel Sidney N. Abramson George W. Accomando Charles Quincy Adams Phyllis Humphrey Adams Randy Adams Christos Agganis Jack and Jayne Ahern Patricia Akowicz Margaret and Orville Alexander Dr. Robert (Buck) Alexander All Family Members 3 Janet and Harry Allaby Abner L. Allen Mr. and Mrs. C. Clifford Allen, Jr. Lucille "Mem" Allen Sally Allphin Carol T. Alpers Phineas Alpers Carol A. Alway Eleanor Ammen Arlene Anderson Bernice Anderson David W. Anderson Dorothy Ann Anderson Edward Anderson Edward H. Anderson 4 Kenneth Anderson Maureen Anderson Morgan Rochelle Anderson Clarice P. Andrews Joseph F. Andrews Michael Andrews Peter E. Andrews Alphonse W. Angelli Maureen Annese-Picard Angelina Antczak Alice Armentrout Richard E. “Dick” Ash Bernard Charles Atkinson Bert and Rita Aube, El Silva, James Wilson, Sr. John and Mary Aulson 5 Lewis Austin Teresa Autuori Maria Azevedo -B- Eric Baade Leo, Dorothy and Dan Bachini Martin Badger Jean Bailey Dr. William E. Bailey Phyllis Baker Louis Balestraci Louis J. Balestraci M. Helen Balestraci Sandra Ball Beverly P. Barber 6 Rev. Robert H. and Mrs. Ruth L. Barber Samuel C. Barchus Sybil Barnard Donald R. Barnett, Jr. Donald R. Barnett, Sr. Theresa Barnett Domenic Barrasso Mr. and Mrs. Allan Barratt Dana R. Barratt Melissa S. Barrowclough Michael J. Barry Palmina "Pam" Barry Robert J. Barry W. Dana Bartlett 7 Mary Ellen and Wilbur Bassett, Sr. Captain Raymond H. Bates Peter W. Beacham Charley Rose Beasley Phyllis Beaulieu Cynthia K. Bedard Gertrude (Blue) Bee Mildred Begin Theresa and John Bekeritis Lianne Belkas George Bellevue Richard Bellitti Teresa Bello A. -

Class of 1965 50Th Reunion

CLASS OF 1965 50TH REUNION BENNINGTON COLLEGE Class of 1965 Abby Goldstein Arato* June Caudle Davenport Anna Coffey Harrington Catherine Posselt Bachrach Margo Baumgarten Davis Sandol Sturges Harsch Cynthia Rodriguez Badendyck Michele DeAngelis Joann Hirschorn Harte Isabella Holden Bates Liuda Dovydenas Sophia Healy Helen Eggleston Bellas Marilyn Kirshner Draper Marcia Heiman Deborah Kasin Benz Polly Burr Drinkwater Hope Norris Hendrickson Roberta Elzey Berke Bonnie Dyer-Bennet Suzanne Robertson Henroid Jill (Elizabeth) Underwood Diane Globus Edington Carol Hickler Bertrand* Wendy Erdman-Surlea Judith Henning Hoopes* Stephen Bick Timothy Caroline Tupling Evans Carla Otten Hosford Roberta Robbins Bickford Rima Gitlin Faber Inez Ingle Deborah Rubin Bluestein Joy Bacon Friedman Carole Irby Ruth Jacobs Boody Lisa (Elizabeth) Gallatin Nina Levin Jalladeau Elizabeth Boulware* Ehrenkranz Stephanie Stouffer Kahn Renee Engel Bowen* Alice Ruby Germond Lorna (Miriam) Katz-Lawson Linda Bratton Judith Hyde Gessel Jan Tupper Kearney Mary Okie Brown Lynne Coleman Gevirtz Mary Kelley Patsy Burns* Barbara Glasser Cynthia Keyworth Charles Caffall* Martha Hollins Gold* Wendy Slote Kleinbaum Donna Maxfield Chimera Joan Golden-Alexis Anne Boyd Kraig Moss Cohen Sheila Diamond Goodwin Edith Anderson Kraysler Jane McCormick Cowgill Susan Hadary Marjorie La Rowe Susan Crile Bay (Elizabeth) Hallowell Barbara Kent Lawrence Tina Croll Lynne Tishman Handler Stephanie LeVanda Lipsky 50TH REUNION CLASS OF 1965 1 Eliza Wood Livingston Deborah Rankin* Derwin Stevens* Isabella Holden Bates Caryn Levy Magid Tonia Noell Roberts Annette Adams Stuart 2 Masconomo Street Nancy Marshall Rosalind Robinson Joyce Sunila Manchester, MA 01944 978-526-1443 Carol Lee Metzger Lois Banulis Rogers Maria Taranto [email protected] Melissa Saltman Meyer* Ruth Grunzweig Roth Susan Tarlov I had heard about Bennington all my life, as my mother was in the third Dorothy Minshall Miller Gail Mayer Rubino Meredith Leavitt Teare* graduating class. -

Early Childhood Interventions: Proven Results, Future Promise and Public Sectors Who Are Considering Investing Resources in Early Childhood Programs

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Support RAND Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND Labor and Population View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Early Childhood Interventions Proven Results, Future Promise Lynn A. Karoly M. Rebecca Kilburn, Jill S. Cannon Prepared for The PNC Financial Services Group, Inc. The research described in the report was conducted for The PNC Financial Services Group, Inc. by RAND Labor and Population, a division of the RAND Corporation. -

The Victor Black Label Discography

The Victor Black Label Discography Victor 25000, 26000, 27000 Series John R. Bolig ISBN 978-1-7351787-3-8 ii The Victor Black Label Discography Victor 25000, 26000, 27000 Series John R. Bolig American Discography Project UC Santa Barbara Library © 2017 John R. Bolig. All rights reserved. ii The Victor Discography Series By John R. Bolig The advent of this online discography is a continuation of record descriptions that were compiled by me and published in book form by Allan Sutton, the publisher and owner of Mainspring Press. When undertaking our work, Allan and I were aware of the work started by Ted Fa- gan and Bill Moran, in which they intended to account for every recording made by the Victor Talking Machine Company. We decided to take on what we believed was a more practical approach, one that best met the needs of record collectors. Simply stat- ed, Fagan and Moran were describing recordings that were not necessarily published; I believed record collectors were interested in records that were actually available. We decided to account for records found in Victor catalogs, ones that were purchased and found in homes after 1901 as 78rpm discs, many of which have become highly sought- after collector’s items. The following Victor discographies by John R. Bolig have been published by Main- spring Press: Caruso Records ‐ A History and Discography GEMS – The Victor Light Opera Company Discography The Victor Black Label Discography – 16000 and 17000 Series The Victor Black Label Discography – 18000 and 19000 Series The Victor Black -

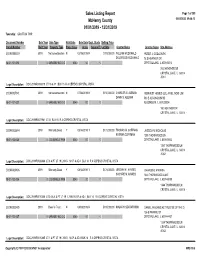

Sales Report

Sales Listing Report Page 1 of 309 McHenry County 05/04/2020 09:46:13 01/01/2019 - 12/31/2019 Township: GRAFTON TWP Document Number Sale Year Sale Type Valid Sale Sale Date Dept. Study Selling Price Parcel Number Built Year Property Type Prop. Class Acres Square Ft. Lot Size Grantor Name Grantee Name Site Address 2019R0006019 2019 Not advertised on mN 02/19/2019 N $115,000.00 WILLIAM MCDONALD PETER J. GODLEWSKI DOLORESS MCDONALD 78 S HEATHER DR 18-01-101-013 0 GARAGE/ NO O O 0040 .00 0 CRYSTAL LAKE, IL 600145018 78 S HEATHER DR CRYSTAL LAKE, IL 60014 -5018 Legal Description: DOC 2019R0006019 LT 16 & 17 BLK 15 R A CEPEKS CRYSTAL VISTA 2019R0027941 2019 Not advertised on mN 07/08/2019 N $150,000.00 CHARLES G. ALEMAN REINVEST HOMES LLC, AN ILLINOIS LIMIT DAWN S. ALEMAN 503 E ALGONQUIN RD 18-01-101-027 0 GARAGE/ NO O O 0040 .00 0 ALGONQUIN, IL 601023004 160 HEATHER DR CRYSTAL LAKE, IL 60014 - Legal Description: DOC 2019R0027941 LT 31 BLK 15 R A CEPEKS CRYSTAL VISTA 2019R0026844 2019 Warranty Deed Y 08/14/2019 Y $172,000.00 THOMAS M. COFFMAN JESSICA N. NICHOLAS KATRINA COFFMAN 1350 THORNWOOD LN 18-01-102-035 0 LDG SINGLE FAM 0040 .00 0 CRYSTAL LAKE, IL 600145042 1350 THORNWOOD LN CRYSTAL LAKE, IL 60014 -5042 Legal Description: DOC 2019R0026844 LT 6 & PT LT 19 LYING N OF & ADJ BLK 14 R A CEPEKS CRYSTAL VISTA 2019R0010406 2019 Warranty Deed Y 04/12/2019 Y $174,000.00 JEREMY M. -

^VOICE to Top ABCD '76 Goal MARCH 26, 1976 VOL

Parishes racing time ^VOICE to top ABCD '76 goal MARCH 26, 1976 VOL. XVIII No. 3 25c As contributions to the continued to arrive at the Arch- half of the families in the Arch- ArchBishop's Charities Drive diocesan Chancery this week, diocese at the time of the Archbishop Coleman F. Carroll meeting on March 10, it is praised the zeal and dedication anticipated that the ABCD of South Florida priests and goal of $2,500,000 will be ex- lauded the generosity of the ceeded. Victim less faithful who have expressed IN VIEW of the sacrificial their concern for the needy spirit of giving already through early donations. exhibited by South Floridians, The drive is continuing Archbishop Carroll said that following the first general there is every indication that report meeting more than one the goal will be met. He week ago when Archbishop reiterated that "this is what Carroll thanked Archdiocesan God intended we should do, priests for their work on the this is our responsibility." drive and noted that many During the weeks since the families had obviously made annual drive — inaugurated 17 sacrifices to increase their years ago by Archbishop pledges of last year. Carroll —began early in IN ADDITION, the Arch- January, thousands of persons bishop cited the "continuing throughout the Archdiocese dedication of men and women have heard first-hand the many in the Archdiocese who have needs of the more than 40 become part of the work of the charitable facilities made Church not only through available by the Church in prayer, sanctification, and South Florida to dependent sacrifice but by personal in- children, youth, drug addicts, volvement in aiding those in unwed mothers, agricultural need." farm workers, the mentally The incomplete total retarded and the aged, through reported at the general meeting donations to the ABCD. -

Palpung Changchub Dargye Ling Prayer Book

Palpung Changchub Dargyeling REFUGE (x3) SANG GYE CHO DANG TSOK KYI CHOK NAM LA Until enlightenment I take refuge, JANG CHUB BAR DU DAK NI KYAB SU CHI in the Buddha, Dharma and the Supreme Assembly, DAK GI JIN SOK GYI PAY SO NAM KYI May the merits from my generosity and other good deeds, DRO LA PEN CHIR SANG GYE DRUP PAR SHOK result in Buddhahood for the benefit of all beings FOUR IMMEASURABLES SEM CHEN TAM CHE DE WA DANG DE WAY GYU DANG DEN PAR GYUR CHIK May all beings have happiness and the causes of happiness, DUK NGAL DANG DUK NGAL GYI GYU DAN DREL WAY GYUR CHIK May all beings be free from suffering and the causes of suffering, DUK NGAL ME PAY DE WA DAM PA DANG MI DRAL WAR GYUR CHIK May all beings never be separate from the supreme bliss which is free from all suffering, NYE RING CHAK DANG NYI DANG DREL WAY TANG NYOM CHEN PO LA NAY PAR GYUR CHIK May all beings live in the Great Equanimity free from all attachment and aversion PRAYER TO THE ROOT LAMA PAL DEN TSAWI LAMA RINPOCHE, DA KI CHI WOR PE DE DEN CHU LA Wonderful, precious Root Guru, seated on a lotus and moon seat above my head, KA DRIN CHEN PEU GO NAY JAY ZUNG TAY I pray that you take me into your care with your vast kindness, KU SUNG TUK JI NGO DRUP TSAL DU SOL And give me the siddhis of body, speech and mind. 2 Palpung Changchub Dargyeling THE SEVEN BRANCH PRAYER CHANG TSAL WA TANG CHURSHING SHAG PA DANG We prostrate and make offerings JESU YIR ANG KULCHI SOL WA YI We confess and rejoice in the virtues of all beings GEWA CHUNG ZEY DAGI CHI SAGPA We ask for the wheel of Dharma to be turned for all beings TAN CHE DZOG PEY CHANG CHUP CHEN POR NGO We pray that the Buddhas remain in this world to teach, We dedicate all merit to sentient beings. -

Language Specific Peculiarities Document for Halh Mongolian As Spoken in MONGOLIA

Language Specific Peculiarities Document for Halh Mongolian as Spoken in MONGOLIA Halh Mongolian, also known as Khalkha (or Xalxa) Mongolian, is a Mongolic language spoken in Mongolia. It has approximately 3 million speakers. 1. Special handling of dialects There are several Mongolic languages or dialects which are mutually intelligible. These include Chakhar and Ordos Mongol, both spoken in the Inner Mongolia region of China. Their status as separate languages is a matter of dispute (Rybatzki 2003). Halh Mongolian is the only Mongolian dialect spoken by the ethnic Mongolian majority in Mongolia. Mongolian speakers from outside Mongolia were not included in this data collection; only Halh Mongolian was collected. 2. Deviation from native-speaker principle No deviation, only native speakers of Halh Mongolian in Mongolia were collected. 3. Special handling of spelling None. 4. Description of character set used for orthographic transcription Mongolian has historically been written in a large variety of scripts. A Latin alphabet was introduced in 1941, but is no longer current (Grenoble, 2003). Today, the classic Mongolian script is still used in Inner Mongolia, but the official standard spelling of Halh Mongolian uses Mongolian Cyrillic. This is also the script used for all educational purposes in Mongolia, and therefore the script which was used for this project. It consists of the standard Cyrillic range (Ux0410-Ux044F, Ux0401, and Ux0451) plus two extra characters, Ux04E8/Ux04E9 and Ux04AE/Ux04AF (see also the table in Section 5.1). 5. Description of Romanization scheme The table in Section 5.1 shows Appen's Mongolian Romanization scheme, which is fully reversible. -

Participant List

Participant List 10/20/2019 8:45:44 AM Category First Name Last Name Position Organization Nationality CSO Jillian Abballe UN Advocacy Officer and Anglican Communion United States Head of Office Ramil Abbasov Chariman of the Managing Spektr Socio-Economic Azerbaijan Board Researches and Development Public Union Babak Abbaszadeh President and Chief Toronto Centre for Global Canada Executive Officer Leadership in Financial Supervision Amr Abdallah Director, Gulf Programs Educaiton for Employment - United States EFE HAGAR ABDELRAHM African affairs & SDGs Unit Maat for Peace, Development Egypt AN Manager and Human Rights Abukar Abdi CEO Juba Foundation Kenya Nabil Abdo MENA Senior Policy Oxfam International Lebanon Advisor Mala Abdulaziz Executive director Swift Relief Foundation Nigeria Maryati Abdullah Director/National Publish What You Pay Indonesia Coordinator Indonesia Yussuf Abdullahi Regional Team Lead Pact Kenya Abdulahi Abdulraheem Executive Director Initiative for Sound Education Nigeria Relationship & Health Muttaqa Abdulra'uf Research Fellow International Trade Union Nigeria Confederation (ITUC) Kehinde Abdulsalam Interfaith Minister Strength in Diversity Nigeria Development Centre, Nigeria Kassim Abdulsalam Zonal Coordinator/Field Strength in Diversity Nigeria Executive Development Centre, Nigeria and Farmers Advocacy and Support Initiative in Nig Shahlo Abdunabizoda Director Jahon Tajikistan Shontaye Abegaz Executive Director International Insitute for Human United States Security Subhashini Abeysinghe Research Director Verite -

1 Phün Tsok Ge Lek Che Wai Trün Pey Ku Thar

SONGS OF SPIRITUAL EXPERIENCE - Condensed Points of the Stages of the Path - lam rim nyams mgur - by Je Tsongkapa 1 PHÜN TSOK GE LEK CHE WAI TRÜN PEY KU THAR YE DRO WAI RE WA KONG WEY SUNG MA LÜ SHE JA JI ZHIN ZIK PEY THUK SHA KYEY TSO WO DE LA GO CHAK TSEL Your body is created from a billion perfect factors of goodness; Your speech satisfies the yearnings of countless sentient beings; Your mind perceives all objects of knowledge exactly as they are – I bow my head to you O chief of the Shakya clan. 2 DA ME TÖN PA DE YI SE KYI CHOK GYAL WAI DZE PA KÜN GYI KUR NAM NE DRANG ME ZHING DU TRÜL WAI NAM RÖL PA MI PAM JAM PAI YANG LA CHAK TSEL LO You’re the most excellent sons of such peerless teacher; You carry the burden of the enlightened activities of all conquerors, And in countless realms you engage in ecstatic display of emanations – I pay homage to you O Maitreya and Manjushri. 3 SHIN TU PAK PAR KAR WA GYAL WAI YUM JI ZHIN GONG PA DREL DZE DZAM LING GYEN LU DRUB THOK ME CHE NI SA SUM NA YONG SU TRAK PEY ZHAB LA DAG CHAK TSEL So difficult to fathom is the mother of all conquerors, You who unravel its contents as it is are the jewels of the world; You’re hailed with great fame in all three spheres of the world – I pay homage to you O Nagarjuna and Asanga.