“Daemonic” Forces: Trauma and Intertextuality in Fantasy Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Papa Ogre Roger Schnitzler Mama Ogre Jamie Hope Little Shrek/Dwarf

Papa Ogre Roger Schnitzler Mama Ogre Jamie Hope Little Shrek/Dwarf Avery Taylor Shrek Jackson Baldwin Fiona Kyrstin Eastman Teen Fiona Cali Olshefski Young Fiona Adrianna Kelly Donkey Andrew Lewis Farquaad Ryan Hacek Dragon Isabella Schnitzler Gingy/Sugar Plum Fairy Ashton Grant Pinocchio Kali Gerretse Big Bad Wolf Jacob Bottoms Pig #1 Joey Fitzgerald Pig #2 Kyle Hacek Pig #3 Colin Smith Fairy Godmother Jessica Hurley Peter Pan Colton Holland Wicked Witch Olivia Farley Mama Bear Alexis Blink Papa Bear Frank Salmons Baby Bear Jathan Coster Elf Hailey Easter Captain Daniel Hill Thelonius Michael St. Aubin Guards/Knights/Duloc Dancers/Rats Hannah Kyllonen, Emily Gain, Lizzy Kooy, Harley Rudish, Olivia Brackney Pied Piper Michael St. Aubin Blind Mouse #1 Lizzy Kooy Blind Mouse #2 Harley Rudish Blind Mouse #3 Olivia Brackney Actors in each Scene ACT 1 Scene 1 Shrek, Little Shrek, Mama Ogre, Papa Ogre, Happy People/Mob Scene 2 Guard, Pinocchio, Wolf, 3 Pigs, Fairy Godmother, Peter Pan, Sugar Plum Fairy, Witch, 3 Bears, Shrek, Elf Scene 3 Shrek, Donkey, Captain of the Guard, Guards Scene 4 Guards, Farquaad, Gingy Scene 5 Shrek, Donkey, Farquaad, Greeter, Duloc Dancers Scene 6 Young Fiona, Teen Fiona, Fiona Scene 8 Shrek, Donkey, 4 Knights, Dragon Scene 9 Fiona, Shrek, Donkey, Dragon Scene 10 Shrek, Donkey, Fiona ACT 2 Scene 1 Fiona, Bluebird, Pied Piper, Rats, Donkey, Shrek Scene 2 Farquaad, Captain, Thelonious Scene 3 Fiona, Shrek, Donkey Scene 4 Donkey, 3 Blind Mice, Fiona, Shrek Scene 5 Donkey, Fiona/Ogress, Shrek Scene 6 Fiona, Shrek, Farquaad, Guards Scene 7 Pinocchio, Elf, Peter Pan, Wolf, Sugar Plum Fairy, Gingy, 3 bears, Witch, 3 Pigs, Fairy Godmother Scene 8 Shrek, Donkey Scene 9 Choir, Bishop, Fiona, Farquaad, Shrek, Fairy Tale Characters, Donkey Finale Everyone . -

Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: a Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English Summer 8-7-2012 Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant James H. Shimkus Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Recommended Citation Shimkus, James H., "Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2012. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/95 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TEACHING SPECULATIVE FICTION IN COLLEGE: A PEDAGOGY FOR MAKING ENGLISH STUDIES RELEVANT by JAMES HAMMOND SHIMKUS Under the Direction of Dr. Elizabeth Burmester ABSTRACT Speculative fiction (science fiction, fantasy, and horror) has steadily gained popularity both in culture and as a subject for study in college. While many helpful resources on teaching a particular genre or teaching particular texts within a genre exist, college teachers who have not previously taught science fiction, fantasy, or horror will benefit from a broader pedagogical overview of speculative fiction, and that is what this resource provides. Teachers who have previously taught speculative fiction may also benefit from the selection of alternative texts presented here. This resource includes an argument for the consideration of more speculative fiction in college English classes, whether in composition, literature, or creative writing, as well as overviews of the main theoretical discussions and definitions of each genre. -

The Ogre Blinded and the Lord of the Rings

Volume 25 Number 3 Article 12 4-15-2007 The Ogre Blinded and The Lord of the Rings Daniel Peretti Indiana University, Bloomington Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Peretti, Daniel (2007) "The Ogre Blinded and The Lord of the Rings," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 25 : No. 3 , Article 12. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol25/iss3/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Applies folk-tale analysis tools to the climactic Mount Doom scene of The Lord of the Rings, finding intriguing roots in the “ogre blinded” motif most familiar to readers from the Polyphemos episode of The Odyssey. Additional Keywords Homer. The Odyssey—Influence on J.R.R. -

From Folktale to Fantasy

From Folktale to Fantasy A Recipe-Based Approach to Creative Writing Michael Fox ABSTRACT In an environment of increasing strategies for creative writing “lessons” with varying degrees of constraints – ideas like the writing prompt, fash fction, and “uncreative” writing – one overlooked idea is to work with folktale types and motifs in order to create a story outline. Tis article sketches how such a lesson might be constructed, beginning with the selection of a tale type for the broad arc of the story, then moving to the range of individual motifs which might be available to populate that arc. Advanced students might further consider using the parallel and chiastic structures of folktale to sophisticate their outline. Te example used here – and suggested for use – is a folktale which informs both Beowulf and Te Hobbit and which, therefore, is likely at least to a certain extent to be familiar to many writers. Even if the outline which this exercise gen- erates were never used to write a full story, the process remains useful in thinking about the building blocks of story and traditional structures such as the archetypal “Hero’s Journey.” Writing in Practice 131 Introduction If the terms “motif” and “folktale” are unfamiliar, I am working with the following defnitions: a motif, I teach on the Writing side of a Department in terms of folklore, is “the smallest element in a tale of English and Writing Studies. I trained as a having a power to persist in tradition. In order to medievalist, but circumstances led me to a unit have this power, it must have something unusual and which teaches a range of courses from introductory striking about it” (Tompson 1977: 415). -

Hn Hn H H Hn Hn

hn hk io il sy SY ek eh hn hk io il sy SY ek eh hn hk io il sy SY ek eh hn hk io il sy SY ek eh hn hk io il sy SY ek eh hn hk io il sy SY ek eh SCHOLASTIC INC. Copyright © 2016 by Ed Masessa All rights reserved. Published by Scholastic Press, an imprint of Scholastic Inc., hn hk io il sy SY ek eh Pub lishers since 1920. scholastic, scholastic press, and associated logos are trade- hn hk io il sy SY ek eh marks and/or registered trademarks of Scholastic Inc. hn hk io il sy SY ek eh The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility hn hk io il sy SY ek for author or third- party websites or their content. hn hk io il sy SY ek eh No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or hn hk io il sy SY ek eh transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other wise, without written permission of the publisher. For information regarding permission, write to Scholastic Inc., Attention: Permissions Department, 557 Broadway, New York, NY 10012. This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Masessa, Ed, author. -

Toward a Theory of the Dark Fantastic: the Role of Racial Difference in Young Adult Speculative Fiction and Media

Journal of Language and Literacy Education Vol. 14 Issue 1—Spring 2018 Toward a Theory of the Dark Fantastic: The Role of Racial Difference in Young Adult Speculative Fiction and Media Ebony Elizabeth Thomas Abstract: Humans read and listen to stories not only to be informed but also as a way to enter worlds that are not like our own. Stories provide mirrors, windows, and doors into other existences, both real and imagined. A sense of the infinite possibilities inherent in fairy tales, fantasy, science fiction, comics, and graphic novels draws children, teens, and adults from all backgrounds to speculative fiction – also known as the fantastic. However, when people of color seek passageways into &the fantastic, we often discover that the doors are barred. Even the very act of dreaming of worlds-that-never-were can be challenging when the known world does not provide many liberatory spaces. The dark fantastic cycle posits that the presence of Black characters in mainstream speculative fiction creates a dilemma. The way that this dilemma is most often resolved is by enacting violence against the character, who then haunts the narrative. This is what readers of the fantastic expect, for it mirrors the spectacle of symbolic violence against the Dark Other in our own world. Moving through spectacle, hesitation, violence, and haunting, the dark fantastic cycle is only interrupted through emancipation – transforming objectified Dark Others into agentive Dark Ones. Yet the success of new narratives fromBlack Panther in the Marvel Cinematic universe, the recent Hugo Awards won by N.K. Jemisin and Nnedi Okorafor, and the blossoming of Afrofuturistic and Black fantastic tales prove that all people need new mythologies – new “stories about stories.” In addition to amplifying diverse fantasy, liberating the rest of the fantastic from its fear and loathing of darkness and Dark Others is essential. -

Dragon Con Progress Report 2021 | Published by Dragon Con All Material, Unless Otherwise Noted, Is © 2021 Dragon Con, Inc

WWW.DRAGONCON.ORG INSIDE SEPT. 2 - 6, 2021 • ATLANTA, GEORGIA • WWW.DRAGONCON.ORG Announcements .......................................................................... 2 Guests ................................................................................... 4 Featured Guests .......................................................................... 4 4 FEATURED GUESTS Places to go, things to do, and Attending Pros ......................................................................... 26 people to see! Vendors ....................................................................................... 28 Special 35th Anniversary Insert .......................................... 31 Fan Tracks .................................................................................. 36 Special Events & Contests ............................................... 46 36 FAN TRACKS Art Show ................................................................................... 46 Choose your own adventure with one (or all) of our fan-run tracks. Blood Drive ................................................................................47 Comic & Pop Artist Alley ....................................................... 47 Friday Night Costume Contest ........................................... 48 Hallway Costume Contest .................................................. 48 Puppet Slam ............................................................................ 48 46 SPECIAL EVENTS Moments you won’t want to miss Masquerade Costume Contest ........................................ -

Shrek Audition Monologues

Shrek Audition Monologues Shrek: Once upon a time there was a little ogre named Shrek, who lived with his parents in a bog by a tree. It was a pretty nasty place, but he was happy because ogres like nasty. On his 7th birthday the little ogre’s parents sat him down to talk, just as all ogre parents had for hundreds of years before. Ahh, I know it’s sad, very sad, but ogres are used to that – the hardships, the indignities. And so the little ogre went on his way and found a perfectly rancid swamp far away from civilization. And whenever a mob came along to attack him he knew exactly what to do. Rooooooaaaaar! Hahahaha! Fiona: Oh hello! Sorry I’m late! Welcome to Fiona: the Musical! Yay, let’s talk about me. Once upon a time, there was a little princess named Fiona, who lived in a Kingdom far, far away. One fateful day, her parents told her that it was time for her to be locked away in a desolate tower, guarded by a fire-breathing dragon- as so many princesses had for hundreds of years before. Isn’t that the saddest thing you’ve ever heard? A poor little princess hidden away from the world, high in a tower, awaiting her one true love Pinocchio: (Kid or teen) This place is a dump! Yeah, yeah I read Lord Farquaad’s decree. “ All fairytale characters have been banished from the kingdom of Duloc. All fruitcakes and freaks will be sent to a resettlement facility.” Did that guard just say “Pinocchio the puppet”? I’m not a puppet, I’m a real boy! Man, I tell ya, sometimes being a fairytale creature sucks pine-sap! Settle in, everyone. -

Mini-Episode 14: High Fantasy

Not Your Mother’s Library Transcript Mini-Episode 14: High Fantasy (Brief intro music) Rachel: Hello, and welcome to Not Your Mother’s Library, a readers’ advisory podcast from the Oak Creek Public Library. I’m Rachel, and you might be familiar with my voice by now because both Leah and I have been recording a whole bunch of mini-episodes while the library is closed due to the Coronavirus pandemic. Ya know, I played that board game once. “Pandemic,” I mean. I thought it was too complex, but that’s coming from someone who periodically forgets the rules of “Yahtzee.” Anyway, yes, at time of recording Oak Creek Public Library is closed, and staff like myself are offering virtual services in lieu of in- person interactions. Practice social distancing with us, and stay safe out there, everyone. Or, preferably, stay safe in there. Like, indoors. At home. You can catch up on being a couch potato by listening to podcasts, or take us with you while you go for a jog around the neighborhood. New media is versatile like that, and exercise is important. Technically. But, back on track. Leah and I are sharing some of our favorite books, movies, and other schtuff [sic]. Since this episode and the few that follow will be going out in May 2020, I thought I’d go with a new format just for the month. Let’s look into specific genres. This episode, as you can see from the title, we’ll explore high fantasy, and I plan to touch on other genres like horror and comedy and…niche…in future eps. -

CLOSE ENOUGH a Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty of California State University, Hayward in Partial Fulfillment of the Re

CLOSE ENOUGH A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty of California State University, Hayward In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Anthropology By Robert A. Blew May, 1992 Copyright © 1992 by Robert A. Blew ii CLOSE ENOUGH By Robert A. Blew Date: iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is impossible to thank everyone who helped with this paper, most of whom did not know they had done so. without their help and encouragement this paper would not have been possible: All those who attended the festivals sponsored by South Bay Circles and New Reformed Orthodox Order of the Golden Dawn (NROOGD), these past few years. Leigh Ann Hussey and D. Hudson Frew of the Covenant of the Goddess for their contributions to the original research. Carole Parker of South Bay Circles for technical editing. Carrie Wills and David Matsuda, fellow anthropology graduate students, for conducting the interviews and writing the essays that were the test of the hypothesis. Ellen Perlman, of the Pagan/Occult/Witchcraft Special Interest Group of Mensa, and Tom Johnson, of the Covenant of the Goddess, for being willing to be interviewed. Lastly, Valerie Voigt of the Pagan/Occult/Witchcraft Special Interest Group of Mensa, for laughing at something I said. iv Table of Contents I. Introduction.. .... .. .. 1 II. Fictional Narrative ................ 3 1. Communication............... 3 2. Projection .............. 8 3. Memory and Perception. 13 4. Rumor Theory .... ...• .. 16 5. Compounding and Elaboration .. ...•.. 22 6. Principle of Least Effort .. 24 III. Test of the Hypothesis ... .. 26 1. Collection Methodology .... .. 26 2. Context and Influences . .. 30 3. -

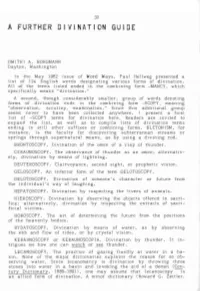

A FURTHER Divination GUIDE Company, 197 Tism

32 -Ologies & A FURTHER DIViNATION GUIDE Company, 197 tism. Take y< METOPOSCOI ination of thE NAUSCOPY. ing ships or DMITRI A. BORGMANN Dayton, Washington OMOPLATOS< blotched or c In the May 1982 issue of Word Ways, Paul Hellweg presented a ONE I ROSCOF list of 124 English words designating various forms of divination. All of the terms listed ended in the combining form -MANCY, which OOSCOPY. [ specifically means "divination." ORNISCOPY. A second, though considerably smaller, group of words denoting ORNlTHOSCC forms of divination ends in the combining form -SCOPY, meaning "observation, scruti ny I exami nation." Si nce this addi tiona I group PYROSCOPY. seems never to have been collected anywhere, I present a first SCATOSCOP) list of -SCOPY terms for divination here. Readers are invited to expand the list, as well as to compile lists of divination terms TERATOSCOI ending in still other suffixes or combining forms. BLETONISM, for All of the instance, is the faculty for discovering subterranean streams or either from springs through supernatural means, as by using a divining rod. Dictionary. 1 BRONTOSCOPY. Divination of the omen of a clap of thunder. Hellweg's lis graphical en CERAUNOSCOPY. The observance of thunder as an omen; alternativ ly as a vari ely, divination by means of lightning. term (see be DEUTEROSCOPY. Clairvoyance, second sight, or prophetic vision. wi th names E of the two s1= GELOSCOPY. An inferior form of the term GELOTOSCOPY. CHAOMANCY GELOTOSCOPY. Divination of someone I s character or future from the individual's way of laughing. COUNTERNEI HEPATOSCOPY. Divination by inspecting the livers of animals. -

Popular Fiction 1814-1939: Selections from the Anthony Tino Collection

POPULAR FICTION, 1814-1939 SELECTIONS FROM THE ANTHONY TINO COLLECTION L.W. Currey, Inc. John W. Knott, Jr., Bookseller POPULAR FICTION, 1814-1939 SELECTIONS FROM THE THE ANTHONY TINO COLLECTION WINTER - SPRING 2017 TERMS OF SALE & PAYMENT: ALL ITEMS subject to prior sale, reservations accepted, items held seven days pending payment or credit card details. Prices are net to all with the exception of booksellers with have previous reciprocal arrangements or are members of the ABAA/ILAB. (1). Checks and money orders drawn on U.S. banks in U.S. dollars. (2). Paypal (3). Credit Card: Mastercard, VISA and American Express. For credit cards please provide: (1) the name of the cardholder exactly as it appears on your card, (2) the billing address of your card, (3) your card number, (4) the expiration date of your card and (5) for MC and Visa the three digit code on the rear, for Amex the for digit code on the front. SALES TAX: Appropriate sales tax for NY and MD added. SHIPPING: Shipment cost additional on all orders. All shipments via U.S. Postal service. UNITED STATES: Priority mail, $12.00 first item, $8.00 each additional or Media mail (book rate) at $4.00 for the first item, $2.00 each additional. (Heavy or oversized books may incur additional charges). CANADA: (1) Priority Mail International (boxed) $36.00, each additional item $8.00 (Rates based on a books approximately 2 lb., heavier books will be price adjusted) or (2) First Class International $16.00, each additional item $10.00. (This rate is good up to 4 lb., over that amount must be shipped Priority Mail International).