The College and Missions: Jane Drummond Redpath1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dalrev Vol61 Iss4 Pp718 734.Pdf (4.730Mb)

P. G. Skidmore Canadian Canals to 1848 In the 1820s and 1830s canal fever struck Canada. The disease was not fatal, although it appeared to be at some stages; it left its victim weakened, scarred, deficient in strength to resist a similar disease soon to come-railroad fever. This paper will present a history ofthat canal fever, detailing the clinical symptoms, the probable source of conta gion, the effects of the fever, and the aftereffects. In more typically historical terms, the causes of the canal building boom will be explored. Three important canals will be described in detail, including their route, construction difficulties and triumphs, the personnel involved, the financial practices used, the political machinations sur rounding their progress, and the canals' effects. In the latter category, there are matters of fact, such as toll revenues, tonnage records, and changes in economic or demographic patterns; and there are matters of judgment, such as the effects of canals on capital investment in Canada, on Montreal's commercial prosperity, on political discontent in Upper Canada, and on esprit de corps. Passing mention will be made of several minor canal projects, aborted or completed. The essay will present a summary of canal building to 1848. By that year, the St. Lawrence canal system was essentially finished, and the Rideau Waterway and Canal were operative. There was an adequate nine-foot waterway for steamers and sailboats from the lower St. Lawrence to the American locks at Sault Sainte Marie. Inland trans portation costs had decreased and Montreal was expected to survive as a significant trading entrepot for the West. -

Behind the Roddick Gates

BEHIND THE RODDICK GATES REDPATH MUSEUM RESEARCH JOURNAL VOLUME III BEHIND THE RODDICK GATES VOLUME III 2013-2014 RMC 2013 Executive President: Jacqueline Riddle Vice President: Pamela Juarez VP Finance: Sarah Popov VP Communications: Linnea Osterberg VP Internal: Catherine Davis Journal Editor: Kaela Bleho Editor in Chief: Kaela Bleho Cover Art: Marc Holmes Contributors: Alexander Grant, Michael Zhang, Rachael Ripley, Kathryn Yuen, Emily Baker, Alexandria Petit-Thorne, Katrina Hannah, Meghan McNeil, Kathryn Kotar, Meghan Walley, Oliver Maurovich Photo Credits: Jewel Seo, Kaela Bleho Design & Layout: Kaela Bleho © Students’ Society of McGill University Montreal, Quebec, Canada 2013-2014 http://redpathmuseumclub.wordpress.com ISBN: 978-0-7717-0716-2 i Table of Contents 3 Letter from the Editor 4 Meet the Authors 7 ‘Welcome to the Cabinet of Curiosities’ - Alexander Grant 18 ‘Eozoön canadense and Practical Science in the 19th Century’- Rachael Ripley 25 ‘The Life of John Redpath: A Neglected Legacy and its Rediscovery through Print Materials’- Michael Zhang 36 ‘The School Band: Insight into Canadian Residential Schools at the McCord Museum’- Emily Baker 42 ‘The Museum of Memories: Historic Museum Architecture and the Phenomenology of Personal Memory in a Contemporary Society’- Kathryn Yuen 54 ‘If These Walls Could Talk: The Assorted History of 4465 and 4467 Blvd. St Laurent’- Kathryn Kotar & Meghan Walley 61 ‘History of the Christ Church Cathedral in Montreal’- Alexandria Petit-Thorne & Katrina Hannah 67 ‘The Hurtubise House’- Meghan McNeil & Oliver Maurovich ii Jewel Seo Letter from the Editor Since its conception in 2011, the Redpath Museum’s annual Research Journal ‘Behind the Roddick Gates’ has been a means for students from McGill to showcase their academic research, artistic endeavors, and personal pursuits. -

A Visit to the Redpath Sugar Museum

Number 61/Spring 2017 ELANELAN Ex Libris Association Newsletter www.exlibris.ca INSIDE THIS ISSUE Refined History: A Visit to the Redpath 1 Sugar Museum Refined History: A Visit to the By Tom Eadie President’s Report 2 Redpath Sugar Museum By Elizabeth Ridler By Tom Eadie Ex Libris Biography Project 2 n October 16, 2016, a group By Nancy Williamson of Ex Libris members ELA 2016 Annual Conference Report 3 toured the Redpath Sugar By Barbara Kaye OMuseum located in the Redpath Taking it to the Streets: 4 Sugar Toronto Refinery at 95 Queen’s Summit on the Value of Libraries, Archives Quay East. Richard Feltoe, Curator and Museums [LAMs] in a Changing World and Redpath Corporate Archivist, By Wendy Newman led the tour, which featured his Technology Unmasked: Hoopla 5 knowledgeable explanations, displays By Stan Orlov of artifacts, and an interesting Richard Feltoe, Curator and Redpath Corporate Archivist, above. Enjoying Church Archives, 5 video about sugar production. lunch at Against the Grain, below. one thing leads to another… Redpath Sugar began as the Canada By Doug Robinson Sugar Refining Company, established Celebrating Canada’s Stunning 6 in Montreal in 1854 by John Redpath Urban Library Branches (1796–1869). Born in Scotland and By Barbara Clubb orphaned when young, Redpath Stratford Festival Archives 6 rose from obscurity to eminence. An By Judy Ginsler apprentice stonemason, he immigrated to Canada at the age of 20. Over time A Memory of Marie F. Zielinska (1921–2016) 7 Prepared by Ralph W. Manning, Redpath became a building contractor with contributions from Irena Bell, involved in the construction of many Frank Kirkwood, Marianne Scott, well-known Montreal buildings, and Jean (Guy) Weerasinghe including Notre-Dame Basilica, the development of sugar production and Library Treasures of Britain: 8 Montreal General Hospital, and the refining in the context of social issues The Royal College of Surgeons Bank of Montreal headquarters. -

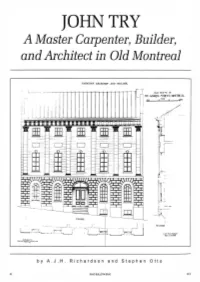

JOHN TRY a Master Carpenter, Builder, and Architect in Old Montreal

JOHN TRY A Master Carpenter, Builder, and Architect in Old Montreal CANADIAN ARCHITEC" AND BUILUER. OUl ltU\ '~1 ·: IS ST. G.\I JI-<!f:l. Sll{l'.t-:T. MON1l{I ':.\L ......____..__''"-"'......__?r-e. _/ ~..,.- ... : ... · ~- . , I I C fril .""'-"" t liunt.'~ M.. \.\oC\., U . ~ by A. J.H. Richardson and Stephen Otto 32 SSAC BULLETIN SEAC 22:2 Figure 1 (previous page). House on St Gabriel Street, Montreal, measured and drawn by Cecil Scott Burgess in 1904 and reproduced in the supplement to Csnsdisn Archit1ct snd Buildsr 18, no. 211 (July 1905). This is the house built for David Ross in 1813-.15. (Metropolitan Toronto Reference Library) Figure 2 (left). Watercolour of the interior of Christ Church Cathedral, Montreal, 1852; James Duncan (1806·1881), artist. (McCord Museum of Canadian History, M6015) ohn Try was likely born in 1779 or 1780; when he died suddenly on 14 August 1855, on holiday at Saco near Portland, Maine, he was said to be seventy-five years Jold and a native of England.1 His exact birthplace has not been identified. Nor is it known where he was trained in his trade as a carpenter, although his rapid success in Canada suggests he arrived here well qualified. Try appears to have emigrated to Montreal in 1807. Confirmation for this year is found in a statement he made in 1841: "I have resided in this City thirty-four years."2 More circumstantial evidence exists in an application that David Ross, a lawyer, made in 1814 to the Governor-in-Chief to allow either "Daniel Reynard Architect and Stucco worker," or "--Roots Plasterer and Stucco worker," both of Boston, to enter the province to work on a large house Ross was building in Montreal (figure 1) .3 Vice-regal consent was needed because a state of war still existed between Britain and the United States. -

Land Capitalization, Public Space, and the Redpath Family Home, 1837-1861 Roderick Macleod

Document generated on 09/25/2021 8:45 a.m. Journal of the Canadian Historical Association Revue de la Société historique du Canada The Road to Terrace Bank: Land Capitalization, Public Space, and the Redpath Family Home, 1837-1861 Roderick Macleod Volume 14, Number 1, 2003 Article abstract The efforts of nineteenth-century Montreal land developer John Redpath to URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/010324ar subdivide his country estate into residential lots for the city's rising middle DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/010324ar class were marked by a shrewd sense of marketing and a keen understanding of the political climate – but they were also strongly determined by the Redpath See table of contents family's need for status and comfort. Both qualities were provided by Terrace Bank, the house at the centre of the estate, and both would only increase with the creation of a middle-class suburb around it on the slopes of Mount Royal. Publisher(s) As a result, the Redpath family home, and the additional homes built nearby for members of the extended Redpath family, influenced all stages of the The Canadian Historical Association / La Société historique du Canada planning and subdivision process, which met with great success over the course of the 1840s. In its use of personal correspondence, notarial documents, ISSN plans, the census, and cemetery records, this paper brings together elements of city planning, political and social history, and family history in order to 0847-4478 (print) provide a nuanced picture of how the nineteenth-century built environment 1712-6274 (digital) was shaped and how we should read pubic space. -

Redimensioning Montreal: Circulation and Urban Form, 1846-1918

Redimensioning Montreal: Circulation and Urban Form, 1846-1918 Jason Gilliland Dept ofGeography McGill University Montreal August 2001 A thesis submitted to the Faculty ofGraduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment ofthe requirements ofthe degree ofDoctor ofPhilosophy © Jason Gilliland, 2001 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1+1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1 A ON4 canada Canada Your fiIB vor,. rétë_ Our 61e Notre référence The author has granted a non L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National LibraI)' ofCanada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies ofthis thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership ofthe L'auteur conselVe la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts from it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permtSSIon. autorisation. 0-612-78690-0 Canada Abstract The purpose ofthis thesis is to explore certain ofthe dynamics associated with the physical transformation ofcities, using Montreal between 1846 and 1918 as a case study. Beyond the typical description or classification ofurban forms, this study deals with the essential problem ofhow changes in form occurred as the city underwent a rapid growth and industrialization. -

A Tour of the Golden Square Mile He Travelled Around the World to Find One

A TOUR OF THE GOLDEN SQUARE MILE HE TRAVELLED AROUND THE WORLD TO FIND ONE, They knew at once that she must be a real princess when she had felt the pea through twenty mattresses and twenty feather beds. Nobody but a real princess could have such a delicate skin. BUT NOWHERE COULD HE GET WHAT HE WANTED. THE PRINCESS AND THE PEA, by Hans Christian Andersen POIS n.m.─ French for "pea", a climbing plant whose seeds are grown for food. Des pois mange-tout, des pois chiches, des petits pois frais. At Le Pois Penché, we constantly strive for excellence, refinement, sophistication and perfection, just like the qualities sought by the prince in his princess, in Andersen’s tale. What is a "BRASSERIE"? ACCORDING TO IMAD NABWANI, OWNER OF LE POIS PENCHÉ A Parisian-style brasserie is all about comfort. It’s about food, wine and service that make you feel welcome, warm, special. And here at Le Pois Penché, that’s precisely what our pursuit of perfection is rooted in: simplicity and comfort. We are among friends here. A steady flow of regulars and new patrons alike keeps the place humming and thrumming with life. As one table leaves, another group of people takes their place. A glass of wine to start, followed by a tartare, perhaps? Good wine and good food can be appreciated at any age. Brasserie cuisine is universal in its appeal. There’s no such thing as a "typical" patron at Le Pois Penché. The makeup of our clientele changes daily – hourly even. -

Montreal's John Ostell

T HEPASSINGOF M ARIANNA O’G ALLAGHER $5 Quebec VOL 5, NO. 9 MAY-JUNE 2010 HeritageNews Gross Outrage across the Border How words nearly brought two countries to war Heart of the Farm Tales and images of rural heritage Man in a Hurry John Ostell: Architect, surveyor, planner QUEBEC HERITAGE NEWS Quebec CONTENTS eritageNews H DITOR E Editor’s Desk 3 ROD MACLEOD Raising a silent glass Rod MacLeod PRODUCTION DAN PINESE Timelines 4 PUBLISHER The Holy Name Hall, Douglastown Luc Chaput THE QUEBEC ANGLOPHONE St Columban Cemetery Memorial dedicated Sandra Stock HERITAGE NETWORK 400-257 QUEEN STREET Reviews SHERBROOKE (LENNOXVILLE) Fencing us in 7 QUEBEC The Heart of the Farm Heather Paterson J1M 1K7 Agitprop in NDG 10 PHONE The Trotsky Rod MacLeod 1-877-964-0409 (819) 564-9595 A Gross Outrage 12 FAX (819) 564-6872 How words nearly brought two countries to war Donald J Davison CORRESPONDENCE A Man in a hurry 18 [email protected] Montreal’s John Ostell Susan McGuire WEBSITE High Ground: The early history of Mount Royal 22 WWW.QAHN.ORG Part II: Mountain real estate Rod MacLeod Milestones 26 The late Marianna O’Gallagher, CM Dennis Dawson PRESIDENT KEVIN O’DONNELL EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Events Listings 27 DWANE WILKIN HERITAGE PORTAL COORDINATOR MATTHEW FARFAN OFFICE MANAGER KATHY TEASDALE Quebec Heritage Magazine is produced six times yearly by the Quebec Anglophone Heritage Network (QAHN) with the support of The Department of Canadian Heritage and Quebec’s Ministere de la Culture et Cover image: “Girls at a fence,” Eastern Townships, c.1900 (McCord Museum: des Communications. -

QHN Summer 2014:Layout 1.Qxd

REDCOATS, DRUMS AND MYSTIC BARNS: QAHN VISITS MISSISQUOI COUNTY $10 Quebec VOL 8, NO. 3 S UMMER 2014 HeritageNews Happy Canada Day! Now move! Finding Meaning in the Madness January in July Ice Palaces and Winter Camping Containing Typhoid Northern Electric’s Emergency Hospital, 1910 QUEBEC HERITAGE NEWS Quebec CONTENTS HeritageNews EDITOR Editor’s Desk 3 RODERICK MACLEOD Redpath’s many mansions Rod MacLeod PRODUCTION DAN PINESE; MATTHEW FARFAN Letters 5 Don’t wait for the obit Jim Caputo PUBLISHER New England Forgues Eileen Fiell THE QUEBEC ANGLOPHONE HERITAGE NETWORK Heritage News from around the province 6 400-257 QUEEN STREET Jim Caputo SHERBROOKE, QUEBEC J1M 1K7 Jim Caputo’s Mystery Objects Challenge #4 7 PHONE 1-877-964-0409 The Play’s the thing: A theatrical photo mystery 8 (819) 564-9595 FAX Press Pedigree 9 (819) 564-6872 A Brief History of the Quebec Chronicle Telegraph Charles André Nadeau CORRESPONDENCE [email protected] Northern Electric’s Heroic Moment 11 WEBSITES The Montreal Emergency Typhoid Hospital, 1910 Robert N. Wilkins WWW.QAHN.ORG WWW.QUEBECHERITAGEWEB.COM Annual QAHN Convention, 2014 14 Matthew Farfan PRESIDENT SIMON JACOBS Canada Day, Montreal-style 18 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR & Elisabeth Dent WEBMAGAZINES EDITOR MATTHEW FARFAN Was Solomon Gursky Here? 20 Literary ghosts in the snow Casey Lambert OFFICE MANAGER KATHY TEASDALE Just Visiting 24 Quebec Heritage News is produced four The world inside the gates of the Trois-Rivières prison Amy Fish times yearly by the Quebec Anglophone Heritage Network (QAHN) with the support Discovering the Ice Palace 26 of the Department of Canadian Heritage and Quebec’s Ministère de la Culture et Montreal’s winter carnivals, 1883-89 Justin Singh des Communications. -

The Redpath Mansion Mystery Annmarie Adams, Valerie Minnett, Mary Anne Poutanen and David Theodore

Document generated on 09/30/2021 12:39 a.m. Material Culture Review "She must not stir out of a darkened room": The Redpath Mansion Mystery Annmarie Adams, Valerie Minnett, Mary Anne Poutanen and David Theodore Volume 72, 2010 Article abstract This paper accounts for private life in a prominent Gilded-Age Montreal URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/mcr72art01 bourgeois household as revealed in the sudden glare of publicity generated by a violent double shooting. We show how the tragic deaths of a mother and her son See table of contents re-enforced fragile class connections between propriety and wealth, family relations and family image. Drawing on diaries, photographs and newspaper accounts, as well as published novels and poetry, we argue that the family Publisher(s) deployed architecture, both the spaces of its own home and public monumental architecture in the city, to follow the dictates of a paradoxical imperative: National Museums of Canada intimacy had to be openly displayed, family private matters enacted in public rituals. The surviving family quickly began a series of manoeuvers designed to ISSN make secret the public event, and re-inscribe the deaths within class norms of decorum and conduct. The house itself, we claim, as a material object, figures in 1718-1259 (print) the complex interplay of inter-connected social relationships, behaviours and 1927-9264 (digital) narratives that produce bourgeois respectability. Explore this journal Cite this article Adams, A., Minnett, V., Poutanen, M. A. & Theodore, D. (2010). "She must not stir out of a darkened room":: The Redpath Mansion Mystery. Material Culture Review, 72, 12–24. -

The Road to Terrace Bank: Land Capitalization, Public Space, and the Redpath Family Home, 1837-1861 Roderick Macleod

Document généré le 26 sept. 2021 13:36 Journal of the Canadian Historical Association Revue de la Société historique du Canada The Road to Terrace Bank: Land Capitalization, Public Space, and the Redpath Family Home, 1837-1861 Roderick Macleod Volume 14, numéro 1, 2003 Résumé de l'article Le promoteur immobilier montréalais John Redpath entreprit au XIXe siècle de URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/010324ar subdiviser ses terres en lots résidentiels destinés à la nouvelle classe moyenne DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/010324ar de la ville. Redpath montrait qu’il avait de fines antennes politiques et un sens aigu du marketing ; cependant, ses démarches avaient surtout pour but de Aller au sommaire du numéro consolider le statut social de la famille Redpath et de hausser son niveau de vie, l’un et l’autre de ces objectifs ayant déjà pour assise Terrace Bank, la maison au coeur du domaine familial. Seul moyen de gravir les échelons supérieurs : Éditeur(s) établir une banlieue pour la classe moyenne autour de ce domaine, sur les flancs du mont Royal. C’est pourquoi toutes les étapes de la planification et du The Canadian Historical Association / La Société historique du Canada lotissement furent déterminées par l’emplacement de la résidence de la famille Redpath et des autres maisons avoisinantes construites pour les membres de la ISSN famille élargie des Redpath. Ce projet d’aménagement foncier fut couronné de succès au cours des années 1840. Basé sur la consultation de correspondance 0847-4478 (imprimé) privée, de documents notariés, de plans, de recensements et d’archives de 1712-6274 (numérique) cimetière, le présent article emprunte à l’urbanisme, à l’histoire politique et sociale ainsi qu’à l’histoire de la famille pour expliquer de façon nuancée la Découvrir la revue formation de l’environnement bâti au XIXe siècle, et pour nous enseigner la manière d’interpréter l’espace public. -

1 CHAPTER ONE the Founding of the Mount Royal Club in 1899 and Its

1 CHAPTER ONE The Founding of the Mount Royal Club in 1899 and its Position within Montreal’s Cultural and Social Milieu In 1899, the year the Mount Royal Club was founded, Montreal was at the apex of its power and influence. It was a time of unparalleled prosperity and exponential growth resulting from the city’s privileged geographical location and the spread of industry, railroads and emerging steamship transportation.1 By 1905 the city was referred to as “the chief city – principal seaport and the financial, social and commercial capital of the Dominion of Canada.” 2 The English and Scottish minority of Montreal dominated the economic life of the city and it was they who profited most from this “unbridled capitalism.”3 In particular, the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway at the west coast of Canada in 1885 and its positioning of the company’s eastern terminus in Montreal, brought wealth and prosperity to the city.4 This powerful corporation worked in tandem with the Bank of Montreal: “symbolically, in 1885, it was the bank’s principal shareholder, vice-president and soon-to-be president, Donald Smith (later to become Lord Strathcona), who hammered in the last spike on the rails of Canada’s first 1 Paul-André Linteau. “Factors in the Development of Montreal” in Montreal Metropolis 1880-1930, Isabelle Gournay and France Vanlaethem eds. (Montreal: Canadian Centre for Architecture, 1998), 28. 2 Frederick George, Montreal: The Grand Union Hotel (Montreal: The Benallack Lithographing Printing Co., 1905), 2. 3 Francois Rémillard, Mansions of the Golden Square Mile: Montreal 1850-1930 (Montreal: Meridian Press, 1987), 20.